eBook - ePub

Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era

Henry Wai-Chung Yeung

This is a test

Share book

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era

Henry Wai-Chung Yeung

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era examines the dynamic ways in which millions of ethinic Chinese in East and Southeast Asian economies organize their economic activities. It analyses how Chinese capitalism has changed under conditions of contemporary globalization and anticipates what the future holds for it. The book challenges the conventional notion of Chinese cpitalism as 'crony capitalism', based around kinship networks and untouched by globalization.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era by Henry Wai-Chung Yeung in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Hybrid capitalism

Demystifying Chinese capitalism

Unpacking Chinese capitalism

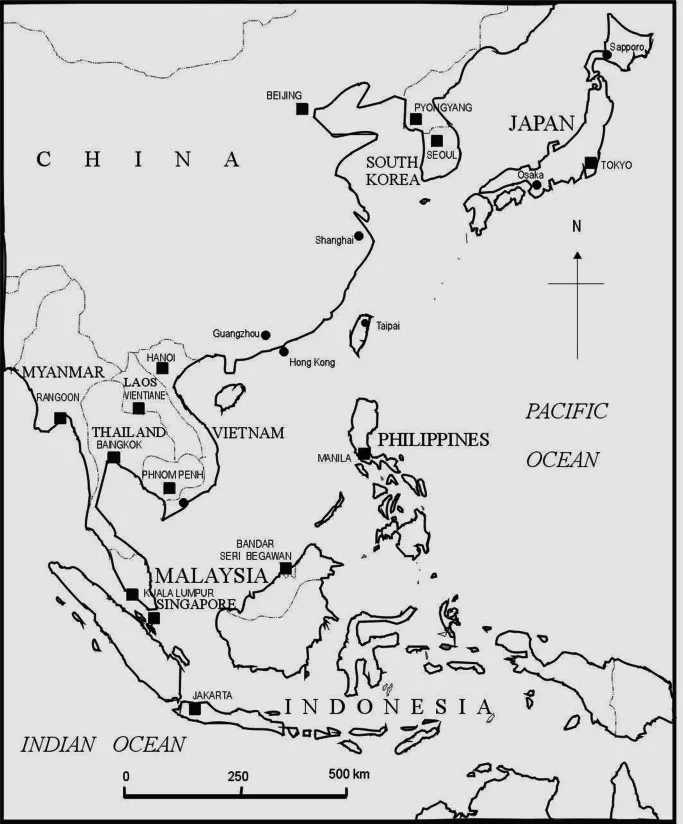

For several centuries, tens of millions of ethnic Chinese people in East and Southeast Asia have engaged in a distinctive form of economic organization through which an informal array of Chinese entrepreneurs, traders, financiers and their closely-knit networks of family members and friends came to dominate the economic sphere of the very host economies they later considered ‘home’.1While deeply rooted in the cultural norms and social values of the traditional Chinese society in mainland China, this form of economic organization has evolved and adapted to dramatically different institutional contexts and political-economic conditions in the host Asian economies. In this book, I use the term ‘Chinese capitalism’ as a heuristic device to describe this historically and geographically specific form of economic organization that refers to the social organization and political economy of the so-called ‘overseas Chinese’2 living outside mainland China, particularly in East and Southeast Asia (i.e. Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam; see Figure 1.1).3 Chinese capitalism is a dominant mode of economic organization in East and Southeast Asia because of not only its economic significance in the host economies, but also its complex and yet intricate social organization and authority systems. The sheer diversity and prowess of economic activities controlled and coordinated by these ethnic Chinese have enabled some of them to become the very foundations of the Asian economies in which they primarily reside and operate. For example, Hong Kong-based Li Ka-shing, whose empire controlled about 16 per cent of Hong Kong’s stock exchange index in 1998 (up from 12.7 per cent in 1988 reported in Redding, 1990: Table 7.4), caused the index to fall by 1.6 per cent on 23 December 1998 with his remarks about the unfriendly business environment in Hong Kong (The Straits Times, 23 and 24 December 1998). In another example, Wee Cho Yaw, the second-generation banker from Singapore and his family-controlled United Overseas Bank succeeded in taking over the fourth-largest Singapore bank (Overseas Union Bank, OUB) on 26 October 2001. After the acquisition, the Wee family held controlling stakes in at least 14 public companies listed on the Singapore Exchange (10 per cent of all listed Chinese family firms). UOB became the largest bank in Singapore, with an international network comprising 273 offices in 18 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, Western Europe and North America.

Figure 1.1 Map of Asia.

Sceptics, nevertheless, may question the independent existence and coherence of this phenomenon known as Chinese capitalism. Building on the important contributions of Redding (1990), Hamilton (1991a, 1996a, 1999a, 2004), Whitley (1992, 1999) and others (see below), I believe that there is a concrete phenomenon, known as Chinese capitalism, to be described and explained. As this book will demonstrate, although this form of capitalist economic organization is changing in a global era, it is logical and reasonable to start an inquiry into Chinese capitalism by assuming it to be a relatively distinct and coherent phenomenon. This is indeed the underlying logic of Redding’s (1990: 9) seminal work The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism in which he

begins with an assumption that there is a distinct and bounded phenomenon to be explained, that it is the culmination of a set of processes which need to be seen historically, and that the beliefs and values of businessmen have a part to play in the understanding of it.

In fact, such an assumption about capitalism’s distinctiveness and coherence has been made since Max Weber’s [1930] (1992) controversial treatise on the spirit of modern capitalism. In his 1920 introduction to the work, Weber [1930] (1992: xxxiv) argued that ‘in modern times the Occident has developed, in addition to this [political capitalism through wars and acquisitions], a very different form of capitalism which has appeared nowhere else: the rational capitalistic organization of (formally) free labour. Only suggestions of it are found elsewhere’. Instead of subscribing to Karl Marx’s view of capitalism as the valorization of capital through the exploitation of labour on a contractual basis (see also Screpanti, 2001), Weber [1920] (1983a: 41) believed that ‘[w]here we find that property is an object of trade and is utilised by individuals for profit-making enterprise in a market economy, there we have capitalism’. He went on to describe and explain this distinct form of modern capitalism in the Occident in relation to a peculiar ethos of accumulating wealth continually for its own sake, the rational utilization of labour and the rise of modern rational organizations (see also Andreski, 1983; Berger, 1986; Saunders, 1995; Silk and Silk, 1996). The spirit of modern industrial capitalism, Weber [1930] (1992: 27, 31) described, refers to ‘that attitude which seeks profit rationally and systematically . . . Where it appears and is able to work itself out, it produces its own capital and monetary supplies as the means to its ends’.

What then distinguishes Chinese capitalism from other forms of economic organization at the beginning of the twenty-first century? My interest does not rest with comparing the success and failure of different varieties of capitalism, a difficult question to which not many scholars other than Weber can provide tentative answers. Rather, I seek to describe and explain in this book the changing dynamics of Chinese capitalism in relation to globalization and how these changes and transformations have led to the emergence of Chinese capitalism as a form of hybrid capitalism. To conduct such a dynamic analysis, however, I need to start with a ‘template’ of what Chinese capitalism might be, as we know it today. This is an equally difficult task because Chinese capitalism, if it exists at all, is embedded within particular political and socio-economic contexts that cannot be easily isolated. As Berger (1986: 16) cautioned in his influential account of the capitalist revolution, ‘it is not easy to excise the capitalist phenomenon from this wider context and look at it [capitalism], as if holding it with pincers under a lens, in any kind of “pure” form’. I do not assume the existence of a ‘pure’ form of capitalism – in its Anglo-American, German or Japanese genres – with which Chinese capitalism can be compared and contrasted. I also recognize the continuously evolving character and transformative power of these diverse genres of modern capitalism. To distinguish Chinese capitalism as a distinct mode of economic organization in East and Southeast Asia today, it is thus reasonable to identify it with a set of common denominators so that subsequent changes and transformations can be discerned. As pointed out by Block (2002: 224),

[i]t is not enough to say that capitalism is a constructed system. The task is to illuminate how it is constructed; to see how a diverse and often contradictory set of practices are welded together to produce something that has the appearance of being a natural and unified entity.

Broadly speaking then, Chinese capitalism has four key defining attributes that, taken together, might satisfy the simple definition of capitalism as ‘production for a market by enterprising individuals or combines with the purpose of making a profit’ (Berger, 1986: 19; emphasis omitted). First, Chinese capitalism refers to an institutionalized mode of economic organization that, until recent decades, has operated largely outside mainland China. It is rationalized and represented by a particular kind of economic institution: the Chinese family firm. This predominance of the family firm, however, is clearly not unique to Chinese capitalism. In fact, more than 75 per cent of all registered companies in the industrialized economies today remain family businesses and a third of listed companies in the Fortune 500 list have families at their helm (Becht et al, 2003).Forty-three of Italy’s top 100 companies are family-owned and 26 of France’s and 15 of Germany’s are also family-owned. In the UK where ownership rapidly dispersed throughout the twentieth century, Franks et al. (2003) found that founding families retained board control well beyond the sale of their ownership stake (see also Chandler, 1990). According to a recent study of corporate ownership around the world (La Porta et al., 1999: 481), even the Microsoft Corporation can be classified as a family-owned firm, with 23.7 per cent controlled by Bill Gates.

In Chinese capitalism, the family firm serves as the key organizational platform or ‘mode of organizing’, in the words of Hamilton (2000), for the continuous accumulation of wealth by ethnic Chinese families that in turn defines the rationality of Chinese capitalism, albeit in culturally specific ways. As Weber [1930] (1992: xxxi–xxxii; original italics) reminded us, ‘[modern] capitalism is identical with the pursuit of profit, and forever renewed profit, by means of continuous, rational, capitalistic enterprise’. While historically such ‘rational’ capitalistic enterprises might not have been developed in mainland China, Chinese capitalism, as I define it here, is organized around a particular social system of economic action and business activities that manifests itself through complex webs of family networks and personal relationships. It is embedded in a peculiar form of political economy in which the ethnic Chinese rule the host economy and leave the political sphere to the reign of indigenous ethnic groups or colonial masters. Chinese capitalism is thus organized and coordinated via neither market relations nor hierarchies of ‘rational’ firms (Williamson, 1975, 1985; Powell, 1990). Rather, it encompasses both markets and hierarchies and configures these capitalist institutions through an informal system of social relationships and family obligations (see Hamilton, 2000).Gordon Redding (1990: 3), a leading proponent of Chinese capitalism, thus observed that:

the Overseas Chinese [sic] have developed one particular form of organization – the family business – and kept to it. Admittedly there are refinements to it, a wide range of sizes and technologies in use, a great variety of products, services, and markets, and an adventurous set of new variations on how to spin it out to larger and larger size, but certain common denominators seem never to be departed from. It remains in essence a family fortress, and at the same time an instrument for the accumulation of wealth by a very specific set of people. It is guarded against incursions from outside influence, and its workings are not publicly known. It is usually run nepotistically, with a benevolent paternalism throughout. Much of its effectiveness derives from intense managerial dedication, much of its efficiency from creating a working environment which matches the expectations of employees from the same culture. It is, in a very real sense, a cultural artifact.

Similarly, Brown (2000: 6) concurred that

[t]he major institution within Chinese business has been the family. The family was the source of funds, contacts and managers. The primacy of the family has been maintained in recent decades, despite rapid diversification and international expansion. In many cases, the Chinese firm had no distinct existence outside the family.

Second, Chinese capitalism is not a mode of economic organization bound within specific territorial boundaries of nation-states. It is indeed a ‘stretchable’ form of capitalism that is embedded, but not limited by, the institutional contexts of the ‘home’ economies. As noted by Hamilton (1996b: 337), ‘Chinese capitalism is not confined to a political space the way many other forms of capitalism have been. Rather, Chinese capitalism fills an economic space’. He further argued that ‘instead of equating it with national economies, capitalism is best conceptualized in terms of the organized economic activities and institutional conditions that constitute it, and countries are best conceptualized as locations where specific activities occur’ (Hamilton, 1999b: 4). Brown (2000: 171) also recognized that ‘the rapidly changing economic and geographical expansion of Chinese firms in Southeast Asia means that a description of Chinese capitalism must jump between different countries, as Chinese businesses jumped’. Defined in this way, Chinese capitalism has no clear-cut political boundaries. Rather, it can only be delimited by the geographic extent and spread of its economic activities. This attribute poses a peculiar problem to the analysis of comparative capitalism and business systems in economic sociology and international political economy because most studies in these two fields focus on the development and institutionalization of different ‘varieties’ of capitalism in distinctive national contexts (e.g. the US and the UK compared with Germany and Japan). Thus, Chinese capitalism should be conceived as a supra-national form of economic organization. This flexible territoriality of Chinese capitalism partly explains why several leading sociologists of Chinese capitalism (e.g. Wong, 1988; Redding, 1990; Whitley, 1992, 1999; Hamilton, 1996a, 1999a, 1999c; Orrù et al., 1997) tend to focus on Hong Kong and Taiwan (instead of Southeast Asian countries) as their primary geographical target of analysis because ethnic homogeneity in these two economies tends to facilitate the analysis of the emergence of a distinctive business system and an economic organization of capitalism. Even in these two ethnic Chinese economies, however, the issues of national sovereignty and territorial boundedness remain highly contested and questionable. Examining the impact of cultural globalization in Taiwan, Hsiao (2002: 52) recently observed that a distinctively Taiwanese business system is infused with influences from all sorts of management styles and practices.

Despite the globalizing of Taiwan’s economy and its businesses over the past few decades, it is clear that neither American nor Japanese management models have supplanted Taiwan’s indigenous business practices. Instead, there is significant fusion of management styles in many of the multinationals operating in Taiwan as well as in many of the local companies that compete in world markets. As a result, there is no pure American, European, Japanese, or Taiwanese-Chinese management model that can best characterize the actual business culture of today’s Taiwan.

Third, Chinese capitalism has achieved some degree of structural coherence and rationality – or ‘spirit’ in the words of Weber [1930] (1992) – through centuries of distinctive cultural practices and social organization originating from then imperial China. This identifiable association of the geographical origin of cultural practices in Chinese capitalism with China as the Middle Kingdom in its historical times differentiates Chinese capitalism from the economic organization of other diaspora groups such as the Jews. As noted by Hwang (1987: 968),

Historically and, to an extent, even in modern contexts, many Chinese have lived in encapsulated communities that are hierarchically organized, with major economic and other resources controlled by a few power figures who could arbitrarily allocate resources. In these settings, it has been imperative to be sensitive to one’s social position and to the kinds of resources that one could elicit and be forced to give up through obligations incurred over long periods of time.

These cultural practices serve as the underlying logic for distinctive economic behaviour and social action among ethnic Chinese. In many ways, most ethnic Chinese identify with this structural coherence and rationality that in turn legitimizes their very socio-economic behaviour. In short, there is a kind of economic culture, defined by Berger (1986: 24) as ‘structures of consciousness’, that constitutes Chinese capitalism. Put in another way, this cultural coherence and legitimation in Chinese capitalism is akin to Storper and Salais’s (1997: 18) idea of the economy as a hybrid object constituted through a diversity of conventions and worlds of production in which actors organize and legitimize their action and behaviour.

The processes by which actors interpret their situations and then enter into pragmatic forms of coordination with other actors constitute the work of constructing the economy. Actors select and build meaningful courses of action in production by engendering rou-tinized, largely implicit forms of coordination, which we call conventions. It is in generating conventions, and then drawing on them in practical activity, that the creative, out-of-equilibrium pathways of development are constructed. There is a great diversity of possible conventions for organizing productive activity, and also a great diversity of possible, conventionally agreed-upon economic tests of whether an activity is economically viable or ‘efficient’.

The world of conventions in which Chinese capitalism is situated can be best described as the interpersonal world, whereby economic activities are conducted and legitimized through interpersonal relationships and networks.

Fourth, unlike its Anglo-American counterpart analysed in the new institutionalism literature (iMaggio and Powell, 1991; Orrù et al., 1997; Whitley, 1999; Guillén, 2001a), Chinese capitalism is actor-centred rather than institution-specific. Whitley (1999: 25) argued that ‘units of economic decision-making and control vary considerably in their constitution and organization across capitalist economies . . . “Firms” are by no means the same sorts of economic actors in different economies’. In the absence of formal legal structures and political systems that are unique to ethnic Chinese outside mainland China, social actors such as families and their business groups have become the primary driving force in Chinese capitalism. To a certain extent, this actor-specific constitution of Chinese capitalism is related to the ‘geopolitical anxiety’ of ethnic Chinese in East and Southeast Asia.4 Their geographical dispersal during the past two centuries and their lack of political power in the host economies of Southeast Asia have greatly increased their geopolitical anxiety that in turn legitimizes their reliance on family-based actors rather than host-country i...