1

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

The role of fiscal policies in promoting economic reform

Mario I.Blejer and Teresa Ter-Minassian

The Festschrift for Vito Tanzi is composed of two volumes. While the companion volume to this book explores various aspects of the macroeconomic impact of fiscal policies, this volume focuses on the role of these policies in the process of economic and structural reform. Both dimensions of fiscal policy have been emphasized in Vito Tanzi’s scholarly, as well as applied, economic policy work. Indeed, the issue of structural reforms has probably predominated, especially in recent years, when, as Director of the Fiscal Affairs Department of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Tanzi spearheaded the policy advice and technical assistance of the IMF to the implementation of reforms in the fiscal area in industrial, developing, and former socialist countries.

As with those in the companion volume, the chapters in this book span a quite broad range of topics, reflecting the varied interests and professional experiences of the authors, several of whom have been directly involved, as policymakers or policy advisers, in the reforms discussed in the chapters. This involvement is reflected in the policy relevance and practical orientation of the analyses.

A common theme that runs through the variety of topics addressed is the evolving role of the state in a process of economic reforms that is aimed at promoting efficient market mechanisms around the world. Over the last fifteen years or so, an increasing number of countries have moved—more or less speedily and decisively—towards liberalization, deregulation, privatization, and generally reducing state intervention in economic life, while opening the economy to external trade and factor movements. Frequently, these economic reforms have paralleled a process of political democratization, decentralization and, in many instances, more participatory and transparent governance. These trends have been most evident in the ongoing process of transition to market economies by formerly centrally planned countries in Eastern Europe, Asia, and the former Soviet Union, but ‘the silent revolution’ —as it is sometimes referred to—has progressed to various degrees in other parts of the world as well.

Does this process of reduced intervention of the state in economic life mean a virtual end to the role of fiscal policy, or rather its redirection? What are the fiscal dimensions of privatization and deregulation? Can tax policies still be used to promote savings, investment, and foreign capital flows? Can they be used to promote environmental objectives? Increased reliance on market mechanisms involves substantial redistributive effects across income groups. What should be the role of expenditure and other fiscal policies in alleviating these effects on the more vulnerable groups of society?

These are some of the questions that the chapters in this book explore, drawing in particular on specific country experiences.

Part I explores the fiscal dimensions of privatization and deregulation. In Chapter 2 ‘The budgetary impact of privatization’, David Newbery develops an analytical framework for assessing the budgetary effects of sales of public enterprises, comparing the cash proceeds of the sales, plus the present value of the future tax receipts from the privatized enterprises, with the loss of transferred profits from the former state-owned firms. An estimation of these magnitudes for a sample of privatized enterprises in the United Kingdom, Chile, Malaysia, and Mexico suggests that in several instances the loss of transferred profits broadly offsets the gain from the taxation of the privatized enterprise, leaving the net sale proceeds as the main benefit from privatization. The implication is that mass privatization through vouchers is unlikely to provide significant benefits to the budget, although it may be the only effective mechanism for quick privatization of large, nonprofitable firms, especially in transition economies characterized by a dearth of private domestic capital.

This latter point is supported by the analysis of ‘Macroeconomic constraints and the modalities of privatization’, by P.Heller, R.Hemming, and R.Chakrabarti. This chapter explores macroeconomic aspects of privatization. It notes that the macroeconomic effects of privatization depend both on how the private sector finances its acquisition of the public assets, and on how the government utilizes the proceeds of the assets sales (e.g. to redeem public debt outstanding, increase public spending, or reduce taxes). The chapter develops a comprehensive taxonomy of various models of assets sales and use of proceeds, and provides supporting empirical evidence of its conclusions, drawing on a sample of country experiences.

The chapter by A.Fernández-Ordoñez and C.Ocaña, ‘A fiscal approach to liberalization policy’, draws attention to the major political economy obstacles to liberalization and deregulation efforts. It notes that regulations which restrict competition are basically quasi-fiscal instruments, involving an implicit subsidy to the protected producers, matched by an equivalent implicit tax on the consumers of the relevant goods. The chapter notes that removal of these implicit taxes and subsidies tends to be made difficult by the fact thatthe benefits of liberalization are small and diffuse, while the costs are concentrated on a small (often vocal and powerful) group, and, for those affected, are likely to be substantial. The chapter points to the crucial role that broad dissemination of information on such costs and benefits can play in overcoming the opposition to liberalization policies. It advocates the preparation of an annual ‘Budget of restrictions on competition’, presenting estimates of the costs of such restrictions, based on the extra margins charged by firms sheltered from competition. The chapter reflects the experience of the authors, who are senior officials of the anti-monopoly authority in Spain.

Chapter 5 by K.Andersson discusses recent experiences with tax reform in the Scandinavian countries. These countries were characterized, from the 1960s to the early 1980s, by a relentless growth of the tax burden, necessitated in turn by a steady growth of public spending, especially in the social sphere. The chapter discusses the adverse side effects of the rising tax burden, especially the stimulus that it provided to debt accumulation by households and firms in an environment of financial deregulation, leading eventually to an asset price bubble and to speculative capital flows.

Tax reforms—involving, in particular, limitation of interest deductions for the income taxes, the replacement of the global income tax with schedular taxes, with reduced rate for income from capital, and a shift towards increased indirect taxation—were implemented in all Scandinavian countries in the late 1980s. The chapter analyzes their effects on households’ savings, labor supply, enterprise borrowing, and asset prices. It concludes that the reforms reduced distortions and contributed to macroeconomic stabilization, in particular by moderating consumption. Their effects could have been, however, more significant if they had been more timely and supported by tighter financial policies.

Chapter 6 by D.Nellor discusses the fiscal and macroeconomic effects of environmental taxes. Going beyond the traditional Pigouvian analysis of such taxes as instruments to discourage pollution by raising its price to match the social cost of environmental damage, the chapter focusses on the case for using environmental taxes for revenue-raising purposes as well. In this perspective, it compares environmental taxes to alternative instruments such as a broad-based consumption tax (e.g. VAT). It concludes that the macroeconomic costs (in terms of output and employment), as well as the distributional costs of environmental taxes, are likely to exceed those for broader-based taxes. This suggests that the optimal rate of environmental taxation should continue to be set on purely Pigouvian criteria. Among various types of environmental taxes, the chapter finds that a tax on energy consumption is preferable on welfare grounds to a tax on energy production (such as the tax on BTU advocated by some in the United States).

Part IV focusses on the distributional impact of economic reform policies, and on options available to policymakers to alleviate the adverse effects of these policies on the more vulnerable groups of society.

In their chapter, S.Chand and P.Shome expand the financial programming framework, frequently utilized in the design of macroeconomic adjustment programs supported by the IMF resources, to incorporate the constraint that policies utilized should not lead to an increase in poverty beyond a certain level. Through this expanded framework they simulate the impact of different policy mixes—in response to an adverse external shock—on a poverty index, and conclude that a combination of real exchange rate depreciation and financial tightening has less adverse impact on poverty than a policy of financial restraint alone. They also trace the effects on poverty of delayed or disorderly adjustment, and conclude that, although these policies may well cushion the impact of an adverse external shock on the poor in the short run, they are unlikely to safeguard their living standards over the longer term.

The chapter by K.Y.Chu and S.Gupta explores in some detail, and with supporting empirical evidence from a variety of transition economies, the adverse effects, particularly in the initial phase, of price liberalization and restructuring of state enterprises, policies that are at the core of the transition process. They show that the specific distribution of these effects among different groups of society depends, in particular, on the specific mix and sequencing of the policies adopted, and on the demographic structure and initial living standards of the country in question. They then proceed to analyze, with the help of a stylized model, the effects of alternative remedial steps that can be taken to provide a safety net to the most vulnerable groups. They analyze, in particular, the differential costs and benefits of generalized price subsidies versus targeted cash benefits, alternative reforms of the pension, unemployment and other welfare benefits, and of the payroll taxes which provide the main source of financing of these benefits. From this analysis, a number of interesting policy conclusions are drawn. In particular, the chapter points to the substantial scope for budgetary savings and improved equity through targeting of social benefits, although it recognizes the practical difficulties of implementing effective targeting mechanisms.

The chapter by E.Ahmad and L.Halligan develops further a particular form of social safety net, aimed at mitigating the impact of price liberalization on the poor. Specifically, it examines the theoretical underpinnings and practical features of the provision at below market prices of marketable ration coupons for essential commodities, the prices of which are sharply increased or liberalized. This scheme, which involves the coexistence of quantity-constrained markets (with below-equilibrium, administered prices) with free markets for the same commodities, is seen as a feasible and cost-effective short-term mechanism of social protection in the early phases of transition.

The final part of the book discusses other selected aspects of the transition process. The chapter by A.Tait and N.Erbas analyzes the effects of a tax-based income policy instrument (the excess wage tax) which has been used extensively in transition economies to promote wage restraint during the period of price liberalization. These effects are analyzed under alternative models of enterprise behavior (profit maximization and maximization of workers’ incomes). The authors find that in the first case, the tax can be effective in curbing wage growth but only at the cost of a decline in output. In the second case, the impact of the excess wage tax is found to depend on the degree of ‘hardiness’ of the enterprises’ budget constraint. The chapter also finds that the revenue effects of this tax are generally small and that its distortionary consequences (in particular the labor market and the wage structure) can be significant.

Chapter 11, by P.Nagy, reviews the evolution of budgetary policies in the final period of the Soviet Union and the early phases of Russia’s stabilization effort. It notes the difficult initial conditions facing the Russian authorities at the outset of stabilization: political chaos, lack of consensus on the reform strategy, uncertainty regarding the future of the ruble zone, collapsing output, and escalating price pressures. These conditions, and the continued reliance on the traditional methods of a command economy (e.g. exclusive focus on cash expenditures of the budget rather than on commitments, pervasive use of extrabudgetary funds, directed credits to enterprises), made fiscal and consequently macroeconomic adjustment very slow during the early 1990s. Nevertheless, important initial steps were taken in structural reforms, in particular price liberalization and privatization of small and medium enterprises, which were instrumental in laying the basis for an improved macroperformance. Although the jury is still out on the extent and durability of the latter, hopeful signs of recovery in economic activity and price deceleration, in a context of firmer financial policies and a reduction of public sector deficits, are beginning to emerge.

The chapter by D.Holland and J.Owens discusses the use and effectiveness of tax incentives in attracting foreign direct investments to transition economies. The chapter is based on the findings of consultations conducted by staff of the OECD with the authorities of a wide range of transition economies. Following a review of the objectives pursued by these countries in seeking to attract foreign investments, and of the nontax factors likely to affect such investments, the chapter presents a comprehensive analysis of both the general features of a tax system that can be expected to have a bearing on foreign investments, and of the specific forms that the tax incentives for foreign investment may take. The respective costs and benefits of alternative schemes are discussed in detail. On balance, the authors’ judgment on the cost-effectiveness of tax incentives for foreign investment is rather negative. They stress that a transparent and agile regulatory framework for such investments, a tax system broadly patterned on international standards, with relatively low rates and broad bases (as well as other economic considerations relating to cost advantages, size of market, and availability of key infrastructures), is likely to prove more effective in attracting a stable flow of productive capital than tax incentives. Among the latter, tax holidays are found to be the least cost effective, and investmentallowances and credits—offered at moderate rates with clear and transparent features, including defined ‘sunset provisions’—are regarded as clearly preferable.

We hope that this brief overview of the varied contributions of this volume to the debate on the role of fiscal policies in economic reform will stimulate the readers’ interest in a close examination of these contributions, as well as induce further academic and applied policy work on these issues.

2

THE BUDGETARY IMPACT OF PRIVATISATION*

David M.Newbery

Vito Tanzi’s extensive publications range over issues of taxation, debt, deficits and the importance of fiscal reform for nurturing sustainable economic growth. His recent studies of fiscal policy for transitional economies bring many of these themes together (Tanzi, 1992, 1993). In soviet-type economies public finance is almost indistinguishable from the organisation of production, accumulation and distribution, managed through the planning system and carried out by large enterprises under ministerial direction. The transition to a market economy raises sharp questions of the role of the state in promoting and undertaking capital accumulation. When assets are privatised, their profits no longer directly return to the exchequer, but nor does the responsibility to finance their investment. With the transfer of assets to private ownership, the state loses the tangible asset backing to its liabilities, of which an important part are future social security and pension obligations. Clearly, privatisation has important effects on the national balance sheet, and thus the national debt, as well as on current government revenue and expenditures. A study of the fiscal effects of privatisation therefore sits happily within the issues that continue to concern Vito Tanzi.

IMPORTANCE OF PUBLIC ENTERPRISES

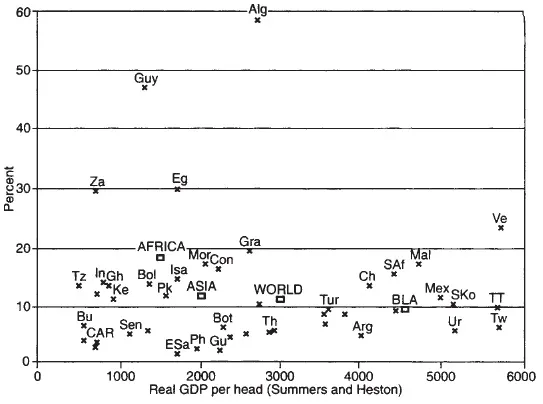

Public enterprises are state-owned production units that market their output, and are thus directly involved in the market process, unlike the state provision of roads, defence, law and order, which are provided, not marketed. World Bank (1995) has collected data on public enterprises in developing countries for the period 1978–91, significantly updating the earlier study of Short (1984) that presented data for the late 1970s. Figure 2.1 shows the share of public enterprises (PEs) in GDP, averaged for the period 1986–91, and graphed against real income per head in 1988 measured using purchasing power parities, taken from Summers and Heston (1991).1 The graph shows the weighted average shares for the world (actually a subset of the developing countries plotted), Latin America (LA, also a subset of the larger countries), Africa and Asia. There is no correlation between income and PE share, and the world average shown is almost identical to the average using Short’s data, which also includes developed countries (Newbery, 1992, fig. 2). PEs have a larger share in Africa than Asia, which exceeds that in Latin America. Developed countries (at least in the 1970s) would be similar in share to Latin America on average.

Figure 2.1 Share of public enterprise in GDP, 1986–91

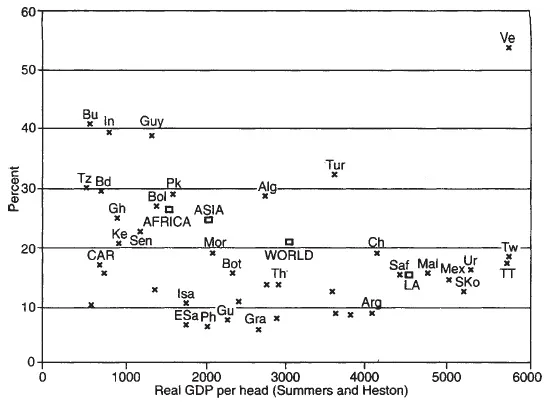

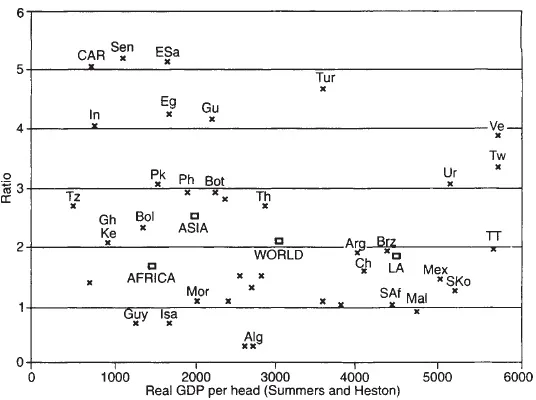

Figure 2.2 shows that PEs have a relatively larger share of total investment than they do of GDP, and this is confirmed by Figure 2.3, which plots the ratio of the investment to output for the PE sector divided by the non-PE sector (defined as the residual). The average relative PE capital intensity is twice that of the non-PE sector, rather higher in Asia and lower in Africa. This is partly explained by the concentration of public ownership in the capital-intensive power, telecommunications, railways and extractive industries, but possibly also by the tendency of PEs to underprice their output in many countries. There is again no correlation between PE investment shares and income, in contrast to the weak negative correlation found in Short’s data (Newbery, 1992, fig. 1 and fn. 2).

Short (1984) was able to study the sectoral allocation of public enterprises and found that developing countries are not so different from developed countries in the pattern of public ownership across sectors. There are good economic reasons to expect public ownership of enterprises in network industries such as post and telecommunications, rail, gas, electricity, and in other natural monopolies such as ports. Natural monopolies will inevitably be subject to price regulation if in the private sector, which makes the investor vulnerable to opportunistic behaviour by the regulator. In most cases capital, once sunk, cannot be removed, and the government may be tempted by domestic consumer interests to hold down prices to unremunerative levels. Fearing this, private investors will be reluctant to invest unless they are confident in the commitment of the regulatory process to fair rates of return. As a result in many developing countries, public ownership was the only viable option.

Figure 2.2 Public enterprise share in investment, 1986–91

In developed countries this argument is less convincing as the United States has demonstrated the viability of regulating investor-owned network industries. Germany has investor-owned electricity utilities, and the UK has recently privatised telecoms, gas, water and electricity. Many European countries nationalised network industries after the Second World War, in some cases to overcome the impediments to coordination created by dispersed municipal ownership, in other cases for a mixture of ideological reasons or the belief that mobilising the high rates of investment after the devastation of the war required government finance.

Figure 2.3 PE relative capital intensity: ratio of investment to output, 1986–91

In the European communist bloc countries before the transition of the late 1980s, most non-agricultural industry was in s...