1 Introduction

Moreover – and more importantly – groups, classes or fractions of classes cannot constitute themselves, or recognize one another, as “subjects” unless they generate (or produce) a space.

Henri Lefebvre (1991)1

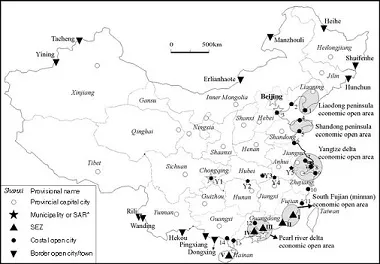

This book is an exploration of urban changes occurring in the coastal region of China in the period since its “opening-up” after the end of the Maoist era in 1976. These changes have been brought about as a consequence of both China’s economic and political reform and its increasing integration into the global economy. Geographically the book focuses on the coastal provinces that were the first areas opened up to foreign investment in the period after 1979. The term coastal areas is the same as the Chinese government’s designation of the eastern region consisting of the provinces of Liaoning, Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan, and the provincial level cities of Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai. For our purposes it also includes the Special Administrative Regions (SARs) of Hong Kong and Macao.2 In the early stages of reform the formation of the Special Economic Zones (SEZs), such as Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Xiamen and Shantou that were created in 1979 and Hainan island in 1988, allowed special economic policies, new systems of management and experiments with land markets that encouraged foreign investment. The policy was expanded in 1984 with the establishment of 14 “open coastal cities” that were given considerable autonomy in fiscal and management matters. This policy initiative was directed towards fulfilling Deng’s vision that these cities would become catalysts for international trade and investment that would flow outwards to the surrounding regions. This action was quickly followed by the extension of these incentives to “Open Economic Regions” in the Yangzi River Delta, Pearl River (zhujiang) Delta and coastal Fujian to be followed by the inclusion of other parts of the coastal zone including parts of Shandong and Liaoning provinces. In the early 1990s Pudong was created as a New Zone in metropolitan Shanghai. It became the focus of major national and municipal initiatives and investment. At the same time many provincial capital cities and five cities along the Yangzi River were granted open city status (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Spatial sequence of China’s opening-up since 1978 (sources: Hu, Zhaoliang, Wang E. Y. and Han M. L. 2000, China Socioeconomic Development and its geographic background, Beijing: Renmin Jiaoyu (people’s education) Press, pp. 135; Liu, Peiqiong (ed.) 1994, Mega trends of China economic development, Guangzhou: Guangdong Jiaoyu (Guangdong education) Press, pp. 52–109.

Notes I

– Xiamen SEZ, II – Shantou SEZ, III – Shenzhen SEZ, IV – Zhuhai SEZ, V – Hainan SEZ.

Fourteen coast open cities: 1 – Dalian, 2 – Qinhuangdao, 3 – Tianjin, 4 – Yantai, 5 – Qingdao, 6 – Lianyunguang, 7 – Nautong, 8 – Shanghai, 9 – Ningbo, 10 – Wenzhou, 11 – Fuzhou, 12 – Guangzhou, 13 – Zhanjiang, 14 – Beihai.

Five Yangzi River open cities: Y1 – Chongqing, Y2 – Yueyang, Y3 – Wuhan, Y4 – Jiujiang, Y5 – Wuhu) 1980: Four SEZs were established (Shenzhen, Xiamen, Shantou and Zhuhai).

1984: Fourteen coast open cities were open.

1985: Five coast economic open areas.

1988: Hainan SEZ was established.

1990: Shanghai Pudong new area was established.

1991: Thirteen border open cities/towns and five open cities along Yangzi river (cities of Chongqing, Yueyang, Wuhan, Jiujiang, Wuhu). All provincial capital cities were listed as open cities.

2000: Large scale inland development began.

* Municipality directly under the jurisdiction of the central government.

SAR – Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macao.

Overall the spatial dimensions of the Chinese “modernization” followed the same principle as was applied to the general economic reform program, i.e. gradualism. Wang et al. (2002) show the spatial sequence of the opening-up of China to the world economy from the late 1970s.3

These economic reforms are also important to understanding the Chinese urbanization processes. First and perhaps most important from the point of view of the formation of “urban spaces” were the development of urban and rural land markets that are discussed in Chapter 2. Cities in the coastal zones were also encouraged to set-up Economic and Technological Development Zones4 where the focus was on the new high-technology industries that would be the leading edge of the technological revolution in Chinese industry that have proved so important in the city-building process of Kunshan discussed in Chapter 8. Undoubtedly the most dramatic example of this process was the case of Shenzhen Municipality that saw the transformation of Baoan County adjacent to Hong Kong from a population of 30,000 in 1980 into a metropolis of seven million by 2000.5

However, in the 1980s when these city forming activities were begun, the more significant process of creating urban space associated with rural reforms has been labeled “rural urbanization.”6 Central to the reforms in the countryside was the abolition of the socialist collective systems administratively centered on the commune and the adoption of a form of contracted “household responsibility system” that gave farmers more freedom in decision-making and incentives to increase production. Many of these changes occurred spontaneously at the local level to be sanctioned later by the state. Another consequence of the relaxation of state control over the rural economy was that it provided a trigger for increased commercialization and industrialization that led to a surge in small industrial enterprises located in the towns and villages of rural areas that was a form of “in-situ urbanization.”7 This tremendous surge in rural industry was initially fueled largely by domestic investment and produced consumer goods for Chinese markets although in south China much of this town (or township) and village enterprises (TVE) development was funded by investment from Hong Kong and Taiwan producing products for global market.8 There has been an ongoing debate concerning the relative importance of these endogenous and external factors in influencing the modernization of China but this study supports the view put forward by some commentators that operation of these two forces created a “two-track” process of urbanization that initially lead to the spread of urban activity into the countryside as well as slower growth in the large urban centers. Thus for a short moment in global history it seemed as if China might be embarked upon an ad hoc process of creating “urban space” in the early phases of the urban transition that was almost unique to world history: one in which the problems of surging rural–urban migration, inadequate urban infrastructure and unemployment that characterized so many developing countries in the early phases of their urban transition might be avoided.

But in the 15 years since Deng’s tour of south China in 1992 the pace of economic and political change has accelerated particularly in the coastal zones as China has become more integrated into the global economy and the forces of globalization became an important driver of a repositioning of urban space in large cities and the political centers of provinces and counties that are discussed in Chapters 3 and 4. This is not to ignore the fact that many other parts of China have also been opened up because they have importance in the strategic vision of the Chinese government. For example China has been following a policy that is dedicated to reducing regional inequality between the coastal and central and western region. However, it is the coastal zones that are the “vanguard” of the “New China” and the areas in which the most rapid economic growth, urbanization and social change are occurring. They have become a major destination of rural migrants especially since the relaxation of its Hukou system.9 The coastal region has also been the major focus of the first policy “experiments” in opening-up the Chinese economy. This dynamic economic growth in the coastal zones of China has been the subject of voluminous research by investigators from both within and outside China. It may be argued that this research forms part of a “global fascination” with one the world’s largest country’s development experiences in an era of increasing globalization. Part of this fascination is the interest in the question of whether, or not, China will eventually move to become a fully developed capitalist society.

It is, therefore, reasonable to ask what new perspective this book brings to understanding of urban change in China. The answer to this question involves consideration of the perspectives that have been used in earlier studies to explain Chinese urbanization. Examples of these approaches include “globalization,” “global–local interactions,” “growth coalitions,” the growth of extended metropolitan regions and the special trajectory of socialism with distinct Chinese characteristics that are discussed in the next three chapters. Despite the difference in these approaches they are in one way or another concerned with exploring the interaction between “space” as an abstract category and “place” as some form of bounded conception of localities that may be physically and culturally demarcated. As Stephan Feuchtwang points out these two intersect in the process of territorial place-making.10 Our choice of the title of the book is very deliberate. We seek to see the production of China’s urban space as a form of modernizing the Chinese state. The construction of urban China is firmly focused on territorial places that in a hybrid way can be both urban and rural space at the same time. This enables us to adopt an approach to study of the Chinese urbanization process as a multi-scaled phenomenon utilizing a more holistic approach that attempts a more comprehensive capture of its political and social dimensions. Laurence Ma captures this process as follows: “Viewed spatially this strategy of nation-building represents a downward shift in state power from a single unitary national scale to multiple local scales, giving rise to a new power matrix in geographic space since the 1980’s.”11 There is another dimension to this argument that should be surfaced. There is an ongoing shift in the study of China that is emphasizing an interdisciplinary and disciplinary as well as an area studies approach to China.12

Our project adopts a perspective that attempts a more holistic approach to the study of Chinese urbanization. Namely it seeks to position Chinese urbanization in the context of global urbanization. In this manner the special features of the Chinese urban experience can be delineated and contribute to a richer analytical portrayal. Of course we realize there are dangers in this approach. The spatial diversity and rapid change of China in the last 28 years means that it is easy to reject broader theoretical paradigms as having only momentary relevance and regional irrelevance. But we are not convinced that these arguments are valid because we would want to argue that there is a national urbanization process in China that can be better understood in its spatial and global context.

The special contribution of this book is that it approaches the study of urban China from the perspective of the overall urbanization process, by which we mean the increase in the numbers of people who live in places defined as urban (although in China this is a very weak measure of urbanization because of the over-bounding of urban areas), the increase in the number of people engaged in non-agriculture (this too is a slippery measure because of multiple income sources not being captured in censuses) and the growth in the value of the nonagricultural production in an urban–rural space. Thus we suggest that the urbanization process, which has often been conventionally defined in terms of the demographic components of urban increase including rural–urban migration and urban natural increase, is too narrow to elucidate all the aspects of the urbanization process. In our view the urbanization process in China is best seen as an integral part of the general processes of development, political, social and economic change that have assumed distinctive configurations in China in the post-1978 era. Within the statistical framing of the urbanization process that the narrow demographic interpretation utilizes there are spatial, political, economic and social changes that cannot be separated from the demographic components of this process. Indeed some writers would argue that urbanization in this broader sense is the way the state enters a new accumulation mode.13 The urbanization process thus becomes a central component of economic growth. In the Chinese context some commentators would argue that this is a central manner by which the state overcomes the contradictions that emerged in the state regulated economy.

Much of the research and writing about Chinese urbanization has been about Chinese cities not about the broader urbanization process.14 The titles and contents of many recent books on urban aspects of China invariably use the word “city” or “cities.”15 But the urbanization process affects other parts of space than spaces defined as cities. As “urban populations” grow they spread outwards and usurp space that is defined as “non-urban” and there is constant ambiguity as to the meaning of this expanding urban space. As urban centers grow economically they attract migrants from non-urban areas that create both positive and negative effects on rural areas. On the positive side the flows of remittances from urban to rural areas provides capital and income to the countryside. A major negative aspect is the decline in rural populations and rural life. Thus rural and urban areas are enmeshed in networks of transactions that make the concept of rural–urban differences outmoded. Therefore the study of the urbanization process requires an approach that sees urbanization as one way of reorganizing nations or, as we choose to label it, the production of urban space. The use of the term “production” is intended to suggest many aspects of the process of urbanization including the physical construction of urban infrastructure, the administrative construction of urban units and the ideological construction of urbanization as a part of the development process.

From our perspective the entry point into this investigation is through an exploration of the “spatiality” of urbanization. Whatever the current fads of postmodernism it is an incontestable fact is that “things urban” must eventually be grounded in territory although academic discourses on urbanization often engage theory rather than the grounded reality of the urbanization process. This does not mean that we want to deny the post-modern insight that the interpretation of the urbanization process involves generating “constructed knowledge” about the process but hopefully our project is informed by an understanding of the empirical facts of the “grounding process” as crucial to any investigation of the urbanization process. Thus one of the important features of Chinese urbanization in the reform era since 1978 has been the political and administrative redefinition of non-urban space, as urban space has become of major importance. In the Western context this has often been explained in terms of processes such as “suburbanization” and outward spread of economic activity from the city core that has not always been associated with the redefinition of the non-urban as urban.

In the Chinese context this process has, until the 1990s been dominated by “in-situ” urbanization in which local agencies have been the prime “developers” of urbanization within an institutional framework that has “allowed” this process of “locally driven” urbanism to develop. This is often described as “urbanization from below.” But in more recent years there has been an emergence of what we describe as “city-centering urbanization” that has been driven by “bureaucratic entrepreneurial elites” based in the administrative cores o...