![]()

1 Introduction, theoretical framework and methodology/approaches

Aims and objectives

In the light of the ever-expanding literature dealing with an encompassing conception of state—society relations that goes beyond the definition of the state as a sheer amalgamation of ‘formal’ institutions, there seems to be a need to revisit the concept of political patronage and try somehow to fit it within this larger sketch of state—society relations. This book aims to analyse the conditions that give rise to patronage in the Egyptian polity. In doing so, it ventures into dissecting some of the recurrent features of this patron—client web in order to examine the main factors that have affected the prevalence of patronage politics in Egypt, particularly throughout the Mubarak phase. Emphasizing the upcoming research questions, this study seeks to provide a better understanding of the factors that have ensured the durability of these patronage networks until the present day. This will be achieved primarily by tackling the issues of transition and liberalization associated with the sort of sociostructural reconfiguration that has been witnessed in the Egyptian polity since the beginning of the twenty-first century.

The main focus of this research will be dedicated to examining the socioeconomic and political roles of the ‘lesser notables’ as intermediaries in the realm of state—society relations.1 In the course of this writing, the term ‘lesser notables’ refers to those middle-level patrons and clients who have flourished at the lower levels of the Egyptian polity and whose sociopolitical agency appears to have been comparatively discarded in the literature pertaining to Middle East politics. The lesser notables constitute an essential segment of the operative cadres in the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) and were also present within the ranks of the former National Democratic Party (NDP), which was dissolved by court order in 2011 in the aftermath of the January 25 revolution.

Research questions

With the seeming mobilization of societal echelons and sociopolitical classes that has taken place in the Egyptian polity in the first decade of the twenty-first century, there is indeed a new realm of relevant political actors who clearly differ from the ones prevalent in the previous periods. For example, the 1980s and 1990s witnessed the rising importance of the political agency of the business community as opposed to the military and the technocratic classes, which had been rather dominant during the socialist heydays of Nasserite Egypt. To what extent has this alteration empowered new classes or echelons of patrons and clients? And can one identify a certain set or sets of neo-patrons and clients who are as a result on the rise in the Egyptian polity? What are the parameters of the socioeconomic and political agency of the lesser notables, those middle-range patrons and clients who play a sizeable role in shaping the dynamics of the popular communities? And what are the major commonalities and differences between those of them who adhered to the ex-ruling NDP in comparison to others who allied with the MB? What role was played by the lesser notabilities in the January 25 revolution, and what are their prospective socioeconomic and political roles in the post-Mubarak phase?

Literature review

Taking into account the informal nature of the majority of the socioeconomic and political activities that this book attempts to scrutinize, primary testimonies from relevant personnel in the dissolved NDP and the MB constitute an essential part of the resources used in this research. As will be elaborated on later in this chapter, the information derived from these sources will be augmented and verified, whenever possible, by data and facts. In order to introduce the subject matter of the research, the literature review will be divided into two sections. The first covers the theoretical framework of postulations dealing with patronage politics and relevant applications to the Egyptian case and, building on that, the second section discusses the major writings that contribute to the methodology and approaches that helped to shape the structure and content of this research.

Theoretical framework

In general, patronage politics could be considered to be an existent theme within almost all political systems. Some analysts have indeed argued that patronage is expected to flourish further in those political systems that are more dependent upon personal rule in their dynamics. ‘It is a dynamic world of political will and action that is ordered less by institutions than by personal authorities and power … but without the assured mediation and regulation of effective political institutions’ (Jackson and Rosberg, 1981: 12).

However, for this aim to be achieved, a series of collaborations and alliances between the ruling powers and several other actors has to take place to make this process of consolidation of power a mutually beneficial course of action that is advantageous to the various parties involved. This is actualized through patronage, which is a complicated web, usually consisting of several patron—client networks (Jackson and Rosberg, 1981). Here, an amalgamation of mutual beneficiaries that expands vertically throughout the system in a top-down approach is evident, and subsequently co-option, rather than coercion, becomes more widespread as an essential medium for exercising political power.

John Martinussen (1997: 193) expands upon this notion by portraying the roles of the patron and the respective client(s) in actualizing the scheme of patronage networks:

The system of patronage … works by the [patron] doling out generously from the public resources and benefits he controls. This patronage is extended to his own clan members and also to a selection of clan leaders whose political support is deemed necessary. The clan leaders can then, at their level within the power hierarchy, use some of their resources in a similar manner to ensure political backing from certain lower-placed clan leaders – and so on, until crumbs from the tables of the mighty eventually fall on the small-scale farmers and other poor people.

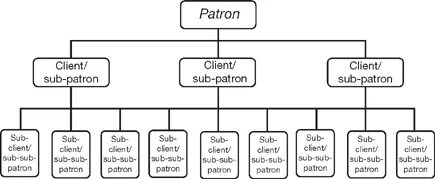

The term ‘clan’ refers here to political alliances and interest groups. Martinussen elaborates that the machinations by which patron—client ties extend from the apex of the political system to its base are best described by the milieu of webs and networks that work their way in a top-down approach. Figure 1.1 shows a generic network of patron—client relations. Of course, sub-patrons and clients eventually emerge as the network approaches the bottom of the hierarchy/polity.

Patronage politics and informal networks

With the inception of the post-1952 phase, the Egyptian polity became a vivid arena for patronage politics whereby informal groups of relatives and friends played a more important role than formal ones in patron—client networks (Moore, 1977). Generally speaking, with the advent of patron—client networks as a primary medium for facilitating political power, the majority of Egyptians, i.e. the common people or the Sha'b , gradually developed a sense of scepticism towards their rulers, along with a conviction of the inefficiency of the formal or official seats of government:

Figure 1.1 The patron—client model.

The Sha'b understand the high costs of participating in formal politics and thus develop other institutions to serve their needs … Elites structure politics so that most people cannot participate in the system or their participation is not much more than a charade.

Singerman, 1995: 9

So, on the one hand, the Sha'b have been suspicious of the government and its intentions, but, on the other, they have been more concerned with the concept of ‘shillal’ or cliques. For them, the importance of the shilla surpasses the importance of any formal sort of union. Henry Moore notes that these shillal or cliques were somehow encouraged in order to form conglomerate units, which was promoted by the growing bloat of the public sector in the 1960s:

The more heavily bureaucracy weighs upon the society; the more likely it is that vertical patron-client networks give way to horizontal shillal. In Egypt, corruption appears to be extensive yet decentralized. As bureaucracy becomes heavier, it is likely to become more corrupt, especially near the top, in the absence of effective political coordination and supervision.

Moore, 1977: 271

More recently, contributors such as Diane Singerman have paid special attention to the concept of informal networks and the sizeable role that such networks have as alternative venues of political participation, especially for those within the lower-middle and lower classes in the Egyptian polity. In what could be described as a relevant anecdote and a potential starting point with regard to the subject matter of the writing at hand, Singerman asserts that little attention has been given to those societal forces in the conventional literature tackling Egyptian politics:

While there are classic works on elite politics in Egypt, its political economy, class formation, interest groups, the bureaucracy, and the military, the politics of the common people or the Sha'b have received little attention. Their political demands, actions, and grievances remain of secondary interest to elite analysis. It has been anthropologists, historians, and sociologists who have told us about the politics of the common people while the “high politics” of the elite … remained the domain of political scientists. However, if one truly wants to consider state-society relations, it seems only natural to try to link up these two arenas of interests.

Singerman, 1995: 5

In addition to the fact that these classes have been, more or less, discarded in the conventional analysis of Egyptian politics, Singerman asserts also that, in practice, such classes are highly influential and have an actual role to play in the overall portrait of the Egyptian polity.

Here, it is also worth noting that informal politics are not exclusively the domain of the lower-middle and lower classes of Egyptian society. In fact, the Egyptian elite also utilize the machinations of informalities, mostly to penetrate the formal structure of the official institutions, yet the end result is to serve some economic or political benefit. Therefore, it is safe to say that the essence of informal networks somehow infiltrates the hierarchy of the Egyptian polity as well. Hence, Singerman says that, when it comes to the lower echelons, those informal networks which were primarily expanded as a result of the lack of formal or official avenues of political participation are in fact open arenas for patrons and clients to flourish:

The Sha'b have turned exploiting the government into a fine art. People in the community who had a particular talent for dealing with bureaucrats or a wide range of connections to elite politicians and officials were sought after and valued … The government was something to “take from”, an outside external force to be patronized.

Singerman, 1995: 39

The characteristics of those people who are capable of connecting with and benefitting from state institutions are actually congruent with the features of what Salwa Ismail described as the biytkabarluh figures in the popular quarters of Cairo. The portrayal of Hajj Saleh, a strongman in Bulaq, exemplifies this: ‘The ethos of someone biytkabarluh involves rights and obligations on the part of the person occupying the position. Moral deference toward [this] figure derives from relations of kinship, regional origin, and the moral standing of the person’ (S. Ismail, 2006: 64) On the one hand, Hajj Saleh's active participation in charitable work gives him the image of a ‘man of good’, whereas, on the other, his links with the police reaffirm his status as a ‘man of power’. Consequently, the Hajj is regularly used by the state apparatus as an influential intermediary with the local community (S. Ismail, 2006). Indeed, here the profile of Hajj Saleh fits the persona of the ‘lesser notables’, described by Ismail as the political powerhouses of Cairo's popular quarters. Interestingly, these lesser notabilities are characterized by an amalgamation of pragmatic and moral statures. These notables in fact constitute the focal point of this research.

January 25: potential implications regarding popular politics in post-Mubarak Egypt

It might still be too early to outline definitive conclusions regarding prospective alterations in popular politics in the post-Mubarak phase. Indeed, the powerhouses of the elite circle of patrons were somewhat disintegrated in the aftermath of January 25, and that was brought about with the dissolution of the NDP and the imprisonment of some of its most influential leading cadres, including Gamal Mubarak. Yet the fact remains that the conglomerate of alliances and networks that constitute the interconnected network of political patronage is somehow embedded within the socioeconomic and political fabric of the middle and the lower echelons of Egyptian society. The prospective changes that will occur with regard to these patronage networks will probably be shaped by the alterations in the political and socioeconomic outlook of the Egyptian state post-Mubarak.

Henceforth, the scope and magnitude of the overall reformulation of the structure of state—society relations is likely to determine the prospects of change concerning patron—client networks. For example, the nature of the social contract between the state and society, exemplified by the socioeconomic policies adopted by the state post-Mubarak, and the degree of empowerment acquired by the populace in terms of participation in the official venues of political decision-making are among the relevant factors here. Such potential reconfigurations may prospectively influence the power dynamics embedded in state—society relations, subsequently redefining the features of patronage politics within the Egyptian polity in the post-Mubarak phase.

The trap of cultural arguments

Patronage politics is not of course a natural ingredient that is embedded solely in the Egyptian or the Arab political culture per se. In fact, similar features of informal politics can be traced in other polities over the globe. Nazih Ayubi prudently notes that:

Although patronage and clientelism have a long history and an elaborate vocabulary in the Middle East … they are not the inevitable outcome of certain essential and permanent cultural traits. They are in reality behavioral correlates to articulated modes of production and attitudinal accompaniments of a stage of transition that requires a higher degree of intermediation between the rural and the urban, between the local and the central, between the public and the private. The study of patron-client relationships, cliques, cronies and informal networks … can be useful and indeed very interesting. Their validity will be constrained however if they are viewed as being exclusively culturally specific, rather than socially and politically contingent.

Ayubi, 1995: 168

Thus, bearing in mind the considerable impact of the prevalent modes of production on the political beliefs and attitudes within a human polity, it is essential to avoid any sort of cultural essentialism that would signify patron—client networks as a peculiar feature of the Arab polity at large, or the Egyptian one in particular. Accordingly, Ayubi states that, for instance regarding the shilla, a concept that was mentioned earlier as an important unit of analysis introduced mainly by H.C. Moore and others, ‘Shillas and other types of cliques and informal networks should not be regarded as a Middle Eastern peculiarity: we know increasingly more about their presence in countries such as Italy, Japan and even the United States’ (Ayubi, 1995: 168).

But here we are faced with an analytical dilemma. If, as stated earlier, patron— client ...