1 EU governance and policy transfer

This chapter sets out an analytical framework with which to approach the study of EU policy transfer. The first part of the chapter outlines the variants of policy transfer found in the mainstream public policy literature, and suggests how we might ‘unpack’ transfer process and outcomes for the purposes of analysis. We then go on to conceptualize European Union policy transfer, beginning from the premise that institutions matter and that transfer processes will reflect the institutional settings in which they take place. The EU’s multifaceted system of governance, it is argued, can be expected to generate multiple forms of policy transfer. We identify three dimensions of transfer. ‘Uploading’ occurs when a policy model drawn from one or more member states is incorporated in EU policy. ‘Downloading’ takes place when EU rules are applied in the member states – either directly by supranational institutions or indirectly by national authorities acting in accordance with EU rules (Börzel 2002). ‘Horizontal’ transfer takes the form of reciprocal policy learning between member states.

To understand the dynamics involved in these three dimensions of transfer we need first to arrive at a typology of EU governance. The second part of the chapter therefore outlines three modes of governance. Uploading occurs in the context of governance by negotiation as EU policy is formulated and adopted. Downloading policy to the member states takes place via a more or less hierarchical mode of governance. Here we distinguish between single tier governance regimes in which ‘hard’ regulatory rules are implemented by supranational institutions and dual-tier regimes in which ‘softer’ rules are transposed and implemented by domestic authorities. Horizontal transfer occurs in a loosely constituted ‘facilitated’ governance regime. In the third part of this chapter we explore the institutional variables which shape the patterns of policy transfer in each of the three modes of EU governance.

The softer variant of two-tier hierarchical governance involves interplay between EU and domestic institutions. Consequently, the final part of the chapter takes the analysis of policy transfer down a level to focus on how EU rules are put into effect at in the member states. Here, we explore the domestic institutional factors which explain how the European regulatory melody may in fact have a distinctive national regulatory tune (Eyre and Lodge 2000). We recognize that globalization and technological advance play a part in changing the face of European utility regulation. We treat these forces as external to our model of EU policy transfer, however, and deal with them in a separate chapter.

Types of policy transfer and learning

Interest in examining policy in other political systems is of very long standing, and could be said to be at the core of comparative politics. Examining how ideas travel is a more recent preoccupation. Political science offers a number of contrasting approaches. Diffusion studies have tended to focus on the patterns involved in the spread of innovations among American state and local government, or the timing of programme adoption across these political systems (Rogers 1962; Walker 1969; and Eyestone 1977). These studies share a ‘pro-innovation bias’ rooted in the belief that political systems in developed countries face common issues and problems, and will therefore gravitate toward similar policy innovations. They also tend to assume that the diffusion of innovation inevitably leads to improvements in policy outcomes. A shortcoming of this type of study from our point of view is its neglect of the mechanisms by which diffusion occurs.

Interest in the diffusion of policy innovation amongst American states has expanded to include studies of international policy convergence (Bell 1973; Collier and Messick 1975; Ross and Homer 1977; Inkles 1981; Kerr 1983). Convergence studies, however, have tended towards economic determinism, arguing that industrialization unleashed forces, such as urbanization and technological advancement, that inevitably led to similar policies and institutions being developed in similarly advanced states (Wilensky 1976). Sharing some of the characteristics of the diffusion literature, these studies were distinctive in that they were not only concerned with the spread of innovation but the increase in the similarity between different political systems in terms of policy goals, instruments, styles and outcomes (Bennett 1991b). While some of these studies touched upon the mechanisms of convergence, these were largely neglected. It was simply assumed that the process was inevitable and beneficial.

More recently, convergence has been attributed to globalization, defined as ‘the cluster of technological, economic, and political innovations that reduce the barriers to economic, political, and cultural exchange’ (Drezner 2005: 841). Although the globalization literature often fails to explain the causal links between globalization and policy convergence, it does identify global civil society, intergovernmental organizations, epistemic communities and capital markets as causal factors (Drezner 2005: 841–2).

Another variant of policy diffusion is regulatory competition. International regulatory competition is seen as the product of techno-economic change and globalization, prompting a global dynamic of ‘liberalizing re-regulation’. In order to attract or retain investment, states competing in the global economy have to develop competitive policies on a range of fronts: tax regimes, employment and social legislation, regulatory policy in a host of economic sectors, and so on. In short, states have had to evolve into ‘competition states’ fighting for inward investment. Paradoxically, this has not led to the much vaunted decline or ‘retreat’ of the state, but has prompted ‘the actual expansion of types of de facto state intervention and regulation in the name of competitiveness and marketisation’ (Cerny 1997: 251). States are forced to turn to one another for information, innovation and ideas. Thus there is a pressure to become more alike so as to ensure there is no slippage in their international competitive position. Regulatory competition thus has echoes of the convergence literature discussed earlier, albeit augmented by recent study of globalization. In our view, however, it does not necessarily bring about convergence, but merely exerts a background pressure on policy. Moreover, the pressure is likely to be subject to significant cross-sectoral variation.

The concept of lesson-drawing places much more emphasis on the processes by which policy travels. It explores the active decision by policymakers to adopt a ‘foreign’ innovation in light of what occurred elsewhere (Bennett 1991a, 1991b; Rose 1991, 1993; Wolman 1992). These studies tended to focus on where ideas originated, what motivated one political system to adopt a policy operating elsewhere, and the role of actors and evidence in the process. Rose (1991, 1993) set out the underlying logic of lesson drawing in terms of decision-makers’ dissatisfaction with the way things are, or their fear of possible sanctions (for example, loss of office) if nothing is done to alleviate the perceived problem. He makes a useful distinction between parallel and interdependent policy programmes (Rose 2005: 18–22). In the former case different states may be grappling with the same policy problems, thus already prompting some interest in lesson-drawing. However, in situations of interdependence, that is where states have close trading relations or are members of the same international organization, ‘national governments must pay attention to what is done elsewhere or risk failure’ (Rose 2005: 20). In terms of policy range and institutional density, for instance in its supranational legal features, the EU exemplifies interdependence and can be expected to be engaged in lesson-drawing.

The lesson-drawing approach has been criticized for its implicit assumptions, first, that the process always conforms to the principles of rationality, and second that it is an essentially voluntary process. For developing countries, it has been noted, lesson drawing often has little to do with the rational or voluntary actions of policy-makers but rather the imposition of ‘solutions’ by international financial institutions (Stone 2000b).

Policy transfer analysis seeks to rectify these shortcomings in the lessondrawing approach. It is understood to mean the process by which the policies and/or practices in one political system are fed into and utilized in the policy-making arena of another political system (see Dolowitz and Marsh 1996: 344). Whilst sharing the lesson drawing literature’s preoccupation with the process by which policy travels it takes as its guiding principle the warning issued by Ross and Homer (1977), that while contact is the key to diffusion, the types of contact that occur can and do vary. The assumptions of the policy transfer literature do not privilege the deliberate efforts of decision-makers to search out new ideas or a rational search for a policy solution. Thus, while alternatives may emerge due to rational observation and evaluation of alternatives, it is just as likely that policy adjustments may be based on poor or inappropriate observations, the imposition of new policies or programmes by force, or the triumph of unstoppable ‘logic’ over the rational needs of the situation.

Two factors lie behind an increased openness to policy transfer. The first is the growth in transnational institutional structures, of which the EU is a particularly developed form. Secondly, advances in telecommunications and information technology have made global communications of almost any kind almost instantaneous, bringing a greater awareness of alternative policy responses. Thus as states are increasingly subject to similar pressures arising from globalization, they can, in part at least, respond by utilizing information about the way other political systems are responding to the same pressures.

Mapping the concepts of policy diffusion, convergence, lesson drawing and policy transfer is complicated, because despite the different assumptions and causal mechanisms deployed, the terms are often used interchangeably (see Knill 2005). There are, however, two key distinctions to be made. The first relates to analytical focus. Whilst the convergence literature’s primary concern is with policy effects, lesson-drawing and policy transfer are concerned primarily with the policy process. Second, whilst the convergence and diffusion literature assumes an ineluctable process of policy approximation, policy transfer is more agnostic as to the effects of the process. This book uses the concept of policy transfer in an open-ended manner. Whilst recognizing that the global policy environment poses common challenges for the EU market integration, it is attentive to cross-sectoral variations in global pressures. Above all, however, we emphasize the central role of institutions as the causal mechanisms of policy transfer.

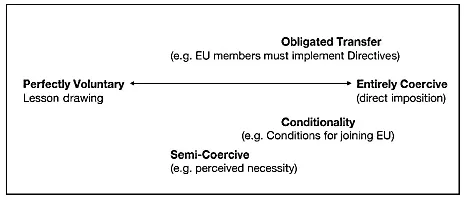

The book is informed by the framework contained in Dolowitz and Marsh (1996) which is based on a critical appreciation of Bennett (1991b) and Rose (1993). The first element of the model is the distinction between voluntary and coercive transfer (see Figure 1.1). This distinction lies along a continuum from completely voluntary (itself closely associated with lesson drawing; Rose 1993, 2005) transfer, to the situations where solutions are imposed on a political system by an outside force related to imperial or colonial situations, or military occupation (Warren 1980; Fieldhouse 1999; Ashcroft 2001).

There are some aspects of the continuum which deserve closer attention. First, the ‘perfectly voluntary’ end of the spectrum is based upon the view that actors choose policy transfer as a rational response to a perceived need – a policy problem or ‘dissatisfaction with the status quo’. A search for new ideas is less costly than starting from scratch, reducing the danger of a ‘policy disaster’. This type of lesson-searching makes an assumption of rationality in the scanning process: ‘The process of lesson-drawing starts with scanning programmes in effect elsewhere, and ends with the prospective evaluation of what would happen if a programme already in effect elsewhere were transferred here in future’ (Rose 1991: 3). In reality, however, much policy transfer takes place within the confines of ‘bounded rationality’, and is typically influenced more by actors’ perceptions and predispositions than by ‘real-world’ situations. At the coercive end of the continuum it is worth noting that national governments may be forced to adopt programmes and policies as part of their obligations as members of international regimes and structures. Dolowitz and Marsh (2000) and Page (2000) have referred to these situations as obligated transfer.

Figure 1.1 From lesson-drawing to coercive transfer.

Dolowitz and Marsh suggest an approach to analysing policy transfer based on four key questions. First, what is transferred? While almost anything can be transferred from one political system to another, the policy transfer literature tends to identify: policy goals and instruments; programmes (Dolowitz 1997, 2000; Peck and Theodore 2001); policy institutions (Stone 2000b; Dolowitz 2001); and ideologies, ideas, attitudes and rhetoric (Dolowitz 1998; King and Wickham-Jones 1999; Deacon 2000; Peck and Theodore 2000). A distinction can also be made between positive lessons, involving some degree of emulation, and negative lessons where policies are rejected because of their perceived failure elsewhere (Dolowitz and Marsh 2000).

A second question is who is involved in policy transfer? Research suggests that there are borrowers and lenders and that these roles seldom change (Robertson 1991; Robertson and Waltman 1992; Rose, 1993). Another way of looking at the participants in policy transfer is to identify the types of political actors involved. Thus Dolowitz and Marsh have identified nine general categories that appear throughout this book: elected politicians; parties; bureaucrats; interest groups; entrepreneurs, experts and consultants; businesses; think tanks; supra-national government; and non-governmental institutions.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have in increasing numbers injected unexpected voices into international discourse about numerous problems of global scope. Especially during the last 20 years . . . interests have become active in political work once reserved for representatives of states . . . In their own ways, NGOs . . . grope . . . towards a modicum of ‘global governance’ . . . NGOs have now become an integral part of the process of setting agendas . . . and in carrying the results not only to governments but to other NGOs and individuals.

(Gordenker and Weiss 1996: 17–18)

The key point is that policy transfer processes are not restricted to governments but involve a wide variety of non-governmental actors. Moreover, from the institutionalist perspective that informs this book, it is important to acknowledge the role of institutions in shaping interactions between actors, and thereby mediating the transfer process. A wide range of institutions may be involved: not only the formal institutions associated with policy-making and (in some cases) the judicial process, but also informal policy norms and administrative cultures which are attached to institutions.

Third, what motivates policy transfer? In one sense the answer is an empirical one, for quite different motivations lie behind the policies and programmes that arise from policy transfer. These motivations, however, fall into two categories; the context-specific or the policy-specific. Context determines the character of a policy transfer. A transfer undertaken during periods of social, political and economic stability is likely to be voluntary (Rose 1993, 2005). In a political crisis, on the other hand, the transfer is likely to have a coercive element, arising from the need to find a political solution (Dolowitz 1997, 1998). Equally, if there is some form of ‘global’ crisis, such as the economic downturn during the mid-1980s, actors are more likely to converge on an agreed upon solution (Levi-Faur 2003b). This will also happen if there is some form of international movement toward an ‘acceptable’ policy, such as the global spread of privatization programmes and workfare policies. A more extreme example is the wholesale transfer of the policies and institutions of the Federal Republic to the ‘new Länder’ (i.e. the former GDR) as a consequence of the failure of the East German system and the urgent need to install new arrangements (Lehmbruch 1992; Jacoby 2000).

Policy-specific circumstances relate to the degree of internationalization. Welfare and employment policies are relatively non-internationalized. Most of the programmes transferred in the development of the British workfare policy were either self-contained, such as Job Clubs, or could be established and controlled by the government independently of outside actors or institutions, such as the Working Families Tax Credit (Walker and Howard 2000; Dolowitz 2004). These types of policies are likely to be the ‘perfectly voluntary’ type of policy transfer. More internationalized policy areas are likely to involve an element of coercion, and those that depend upon international organizations are likely to involve conditionality as well.

The fourth question relates to policy outcomes. In abstract terms, four potential types of transfer-effect may be identified (Rose 1993: 30–1; Dolowitz and Marsh 2000: 13). Emulation or copying is the strongest form of transfer, entailing the ‘borrowing’ of a policy model more or less intact from another jurisdiction (inevitably there will be some adaptation to accommodate contextual differences). Synthesis involves combining elements of policy from two or more different jurisdictions. Influence suggests a weak form of transfer in which the external exemplar serves merely as an inspiration for a new policy, but where institutional design occurs either tabula rasa or draws on extant domestic policy norms. Finally, the abortive variant occurs where a putative transfer is blocked by veto actors in the borrower jurisdiction. Beyond these heuristic categories the form that transfer takes is best explained empirically.

A final point may be made before we proceed to apply this framework to the European Union context. It is generally insufficient to examine transfer in a snapshot form. Policy transfer is unlikely to be a one-off event but is more likely to entail further ‘learning-by-doing’ as policy is put into operation, and subjected to review. Thus a longitudinal study is required to capture the shifting processes involved. This is particularly important in the EU context where policy-making typically involves protracted negotiations, where policy develops incrementally, and where implementation often entails further legislation across the member states.

Policy transfer and EU governance

Although exchange within international organizations is seen as an important factor in the transfer of policy between countries (Dolowitz and Marsh 2000: 6–7), the policy tr...