![]()

1 Truth recovery for missing persons and the global diffusion of ‘truth’

A few years before the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, Federico García Lorca said: ‘In all countries death is an end. It comes, and the curtains are closed. Not in Spain. [. . .] In Spain the dead are more alive than in any other country in the world’ (cited in Spicer 2006: 10). His words proved prophetic. Executed in the first month of the civil war (July 1936) and thrown into an unmarked grave in the region of Granada (Gibson 1979), this prominent poet and playwright is one of approximately 30,000 victims of the Spanish Civil War still lying in mass graves.1 Today, his death continues to haunt Spain more than seven decades after his execution.

The recent wave of exhumations taking place throughout Spain has made tracing Lorca’s burial site more feasible. However, this prospect instigated a heated debate between his family (who oppose exhumation and re-burial, because they want him to rest in peace) and leading intellectuals, who insist that the execution of the poet symbolizes a repressive era and, as such, his exhumation will not only symbolically expose this Francoist repression, but more importantly will detach the country from this legacy. In effect, Lorca encapsulates a central debate in contemporary Spanish society: should the country ‘unearth’ the truth and historical memory related to the civil war or is it better to continue to ‘silence’ the divisive past?

The impact of civil war on Spanish society was so traumatic that even 70 years after its conclusion people are reluctant to talk about it. Added to this, the death of General Franco was followed by a transition to democracy founded on the institutionalized pact of silence over past atrocities. Recently, however, this pact has been challenged. A wave of new social movements, the most visible of which is the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH),2 have emerged since 2000 with two primary objectives. The first, and more fundamental, objective is to unearth the remains of those lying in unmarked mass graves and provide them with a decent burial. The second is to exert pressure on the promotion of policies of public acknowledgement of the suffering of (Republican) victims of the Spanish Civil War and, more generally, to recover historical memory. Both have achieved relative success: by the end of 2007, more than 3,000 victims had been exhumed and identified (Congram and Steadman 2009: 162); by the first quarter of 2010, more than 1,850 mass graves had been re-opened. In addition, in October 2007, the Socialist Government passed the Law of Historical Memory, which satisfies most of the demands of these associations: denouncing Franco’s regime; banning public symbols that commemorate Franco or his allies; mandating local governments to finance exhumations of mass graves; declaring the summary military trials during the Spanish Civil War and Francoist dictatorship as ‘illegitimate’; opening up military archives; and offering other measures of moral, symbolic and economic repair to all victims of the war.3

Spain is not the only Mediterranean country in the European Union (EU) currently dealing with its ghosts. During two waves of violence in Cyprus, the intercommunal violence (1963–1974) and the subsequent Turkish invasion (1974), approximately 2,000 Greek-Cypriots and Turkish-Cypriots went missing. Disappearances were political acts deployed at times by both communities to cleanse the island of the presence of the ethnic ‘other’ and fulfil official political objectives. In the 1960s, hundreds of Turkish-Cypriots were abducted, executed and buried in remote areas by Greek-Cypriot extremists in an effort to intimidate the Turkish-Cypriot community and promote the much-desired enosis (unification) with Greece (Patrick 1976). In the summer of 1974, it was the turn of the invading Turkish Army, with the collaboration of Turkish-Cypriot paramilitaries, to use this instrument to promote their own political objective of Taksim (partition).

The social representation of victim groups as ‘moral beacons’ and the subsequent instrumental exploitation of their suffering to construct ‘cultures of victimhood’ constitute central features of most societies emerging from communal violence (Breen-Smyth 2007: 76). Hence, after the cessation of hostilities (1974), the issue of the missing was again politicized, this time to legitimize official positions adopted by the two sides in negotiations for the reunification of the island. For the Greek-Cypriot community, these persons are still ‘missing’ (yet to be found), revealing their willingness to frame the problem in human rights terms in a bid to garner global support and attribute blame to Turkey for the ongoing suffering of Greek-Cypriots (Sant Cassia 2005: 22). By way of contrast, Turkish-Cypriot authorities perceived their own missing to be ‘martyrs’ (şehitler), who sacrificed their lives to protect the community from Greek-Cypriot repression. In short, the problem was deployed by both sides to symbolize the impossibility of peaceful coexistence and, ultimately, to legitimize the policy of partition (ibid.). Over the decades, for both societies, the problem of the missing has become a ‘chosen trauma’ (Volkan 1997: 49).

Even so, in 2004, a bi-communal agreement was reached to resume the activities of the Committee on Missing Persons (CMP) – a mechanism established in 1981, but never operationalized. Surprisingly, by 2012, it was probably the most successful bi-communal project on the island.4 By February 2013, 1,012 bodies had been exhumed and 477 identified through its activities (CMP 2013).5 However, the process has caused extensive political debate. On the one hand, the fruitful cooperation between Greek and Turkish-Cypriot scientists in the CMP,6 along with the resolution of one of the most intractable issues of the Cyprus conflict, lends credence to the argument that these processes have the potential to act as building blocks of rapprochement and reconciliation. On the other hand, equally legitimate arguments are put forward by more sceptical observers, who say that if the only breakthrough is the exhumation of the missing, without even prosecuting those responsible, the prospects of reconciliation remain minimal.

Irrespective of the prospects for a political solution to the Cyprus problem, the CMP has provided many families with some form of closure in one of the prickliest issues of the Cyprus problem. The focus of this analysis is on why the two societies could not resolve these issues for decades and, more interestingly, why they recently changed their minds and re-opened this painful chapter. This phenomenon of delayed justice – also called ‘post-transitional justice’ – has gained ground over the past decade (Aguilar 2008; Collins 2010). For example, following Chile and El Salvador, Brazil and Turkey recently decided to set up fact-finding commissions, dealing with the problem of their disappeared and the traumatic past more broadly (Collins 2010; The Economist 2010).

Interestingly, despite similar background conditions, Greece remains resistant to this trend, challenging both theory and regional experience. One of the biggest unopened mass graves in Europe, containing approximately 700 to 800 victims of the Greek Civil War in 1940s, is in northern Greece. Despite similar or even more conducive conditions for truth recovery, including the ‘ruptured’ transition to democracy in 1974 and the early incorporation of political parties representing the defeated into mainstream politics, this grave remains closed, and issues related to past human rights violations have been neglected. Along with considering why some societies decide to act, the present work asks why others, such as Greece, resist post-transitional justice.

Transitional justice and truth recovery

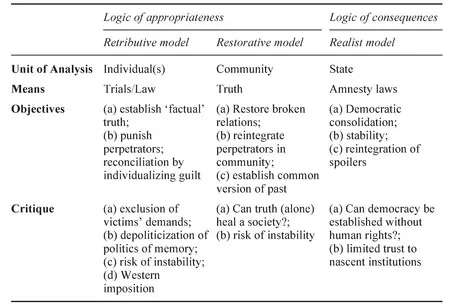

Trials, truth commissions, policies of lustration, commemorations, revision of history textbooks and apologies have attracted the lion’s share of academic attention in transitional justice literature as the most appropriate means to address a violent past.7 The literature proposes the deployment of an appropriate combination of tools to achieve reconciliation and heal fractured relationships in societies emerging from conflict. Two broad clusters of theory have emerged from this overarching approach. The first, guided by a ‘logic of appropriateness’, argues for the need to re-evaluate past human rights abuses as a central prerequisite to reconciliation; this group is subdivided into scholars promoting a retributive/punitive approach in dealing with past human rights abuses and those supporting a more ‘restorative’ conceptualization of justice (Snyder and Vinjamuri 2003: 7).8 The second has been guided by realpolitik considerations and subscribes to the view that it is not always possible or even necessary to tackle the past – at least in the period following the transition – to achieve reconciliation. Table 1.1 encapsulates the main differences of these approaches to transitional justice. As the table makes clear, while reconciliation is a common objective, the approaches differ considerably in their choice of instruments with which to promote reconciliation (trials, truth and amnesties), their units of analysis (individual, community and state) and their conceptualization of reconciliation per se.

Table 1.1 Summary presentation of Schools of Transitional Justice

The common thread linking scholars subscribing to the ‘logic of appropriateness’ is the belief that tackling the past in the aftermath of a conflict or an authoritarian regime constitutes a moral imperative. Following this line of argument, the undeserved suffering of the victims (and/or their relatives) should be acknowledged (Biggar 2003). Within this ‘idealist’ body of literature, there are both retributive and restorative strands.

One the one hand, it has been argued that in societies emerging from mass human rights abuses ‘justice should be done’. Retributive justice constitutes a universally acceptable model of acknowledgement (Orentlicher 1991), whose legitimizing moment is the post-World War II Nuremberg trials. In this view, societies that acknowledge (factual) truth about the violent past have better prospects of strengthening the rule of law and respect for human rights and, more generally, of educating citizens in democratic practices (Elster 2004; Kaminski et al. 2006; Long and Brecke 2003; Popkin and Roht-Arriaza 1995). Efforts to compromise justice by using other forms of acknowledgement – such as amnesties or even truth commissions – are eschewed (Méndez 2001: 32). Proponents say punitive approaches that individualize guilt onto specific perpetrators prevent societies from attributing responsibility to whole communities – a significant cause of political violence. Finally, truth-seeking through retributive measures produces an authoritative version of the past – based on ‘uncontested’ evidence – which prevents deployment of the past for political purposes (Orentlicher 1991).

Equally important is the ‘deterring function’ of justice in post-conflict settings: preventing potential spoilers from engaging in similar heinous activities in the future. Recent research shows that states are increasingly deploying policies of accountability to deal with past violence, not only for strategic reasons, but also because they domesticate international accountability norms (Kim and Sikkink 2010; Sikkink 2011). The wider diffusion of these accountability norms has the potential to realize the Kantian/liberal peace thesis, whereby ultimately all democratic societies will not go to war with each other, setting the stage for global reconciliation. And in this respect, it is true that over the past few decades, a growing number of post-conflict societies have adopted retributive models of justice, leading to a ‘justice cascade’ (Sikkink 2011).

Scholars subscribing to this logic of appropriateness frequently adopt restorative arguments to justify the acknowledgment of past human rights abuses, such as enforced disappearances. In essence, truth recovery is seen as both a moral imperative and the most effective seed with which to yield a harvest of peace, stability and reconciliation (Feher 1999; Kiss 2001). As Michael Ignatieff puts it, the objective of truth recovery is ‘to reduce the number of lies that can be circulated unchallenged in public discourse’ (1998: 173). Truth recovery has the potential to uproot long-standing myths that serve as the founding tenets of collective (national) identities that bolster cultures of victimhood (Galanter 2002; Gibson 2006; Hayner 1996, 2002; Norval 1998; Rosenblum 2002). Establishing an official version of truth not only ‘breaks the cycle of hatred’ (Minow 2002), but under certain circumstances could contribute to forgiveness (Philpott 2006; Torrance 2006), while revised collective identities could set the stage for intergroup reconciliation (Kelman 1999).

The healing power of truth is central in restorative approaches, precisely because the unit of analysis is the community (relations). In restorative forms of justice, trading truth for amnesties is not perceived as handing out immunity; rather, the healing function of truth recovery is deemed a prerequisite of reconciliation and, therefore, a superior form of justice (Asmal et al. 1996; Boraine 2000). If Nuremberg is the legitimizing myth for scholars subscribing to retributive justice, then the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission is the standard for restorative approaches.

Not surprisingly, scholars subscribing to the ‘logic of consequences’ (Snyder and Vinjamuri 2003: 7) often disagree with the idealists. They argue that because (negotiated) transitions/peace agreements are particularly fragile processes (Higley and Burton 1989; Hesse and Post 1999; Licklider 1995), any effort to comprehensively address the past may upset certain people who perceive any truth recovery initiative as blatant scapegoating, causing them to become spoilers and endangering the transition or implementation of a peace settlement (Newman 2002; Vinjamuri and Snyder 2004: 355). It is true that an official acknowledgement of the past constitutes a legitimate goal, but the overarching objective of any transition/peace settlement is the consolidation of democratic institutions and the rule of law. As realist scholars consider the state as the main unit of analysis, in principle, this is the only possible form of reconciliation. If this requires the sacrifice of a comprehensive screening of past human rights abuses, then societies should be ready to adopt amnesties that could contribute to peace. As Snyder and Vinjamuri say: ‘Justice does not lead; it follows’ (2003: 6).

In essence, the decision to address the past or to avoid it depends on the balance of power between the former enemies during the transition. Samuel Huntington’s findings in The Third Wave, where he scrutinizes countries experiencing transition during the so-called ‘third wave’ of democratization, indicate that ‘in actual practice what happened was little affected by moral and legal considerations. It was shaped almost exclusively by politics, by the nature of the democratization process, and by the distribution of political power during and after the transition’ (1991: 212). Therefore, scrutinizing the past is not a normative decision but a political one and, as such, any measure that might contribute to the stability and consolidation of the regime can be legitimately used, even if this requires the adoption of amnesties, impunity or forgetting (Mallinder 2007; Meister 1999).

Truth recovery is to be expected only in cases where, during transition, the violators of human rights are weak and lack sufficient power to negotiate amnesties (Snyder and Vinjamuri 2006). Scholars in this camp underscore successful reconciliation in several societies that deployed amnesties during the third wave of democratization, such as Spain.9

All in all, the three strands of the literature refer to the same objective, reconciliation, but adopt rather different conceptualizations of reconciliation, focus on different levels of analysis and prioritize different tools. It is not mere coincidence that all three are dominated by scholars coming from different disciplines. Broadly speaking, legal scholars dominate and promote retributive approaches, theologians and psychologists support a restorative justice, while political scientists adopt a state-centric approach, guided by realpolitik considerations. The important point is that all support a different type of truth regarding missing persons, so it is worth taking a close look at the conception of truth in the literature.

The concept of truth and a critique of the literature

Truth, transitional justice and reconciliation are relatively new concepts that emerged concurrently with a wider normative turn in the early 1990s. The emergence of truth recovery as a central tool in transitional justice is a stark illustration of the wider volte face. In the 1980s, truth commissions were established in Latin American countries as a ‘second-best’ alternative, given the impossibility of trying those responsible for the disappearances and other heinous human rights breaches. Since the 1990s, however, the functions of truth have been considerably broadened. In the aftermath of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), truth came to be valued as a universally acceptable model of peace-building, based on the argument that revealing is healing (Hirsch 2007). In fact, truth is now a central tool in the transitional justice toolbox of the most prestigious international organizations, including the United Nations (UN) (UN 2004). Nevertheless, it remains questionable whether this ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach reflects the demands of local communities (Richmon...