- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This truly internationally-focused book is a readable, comprehensive guide to the economic geography of the world's financial centres that is as enjoyable to read as it is informative. All students and academics involved with economic geography as well as professionals in the banking and finance industries will find Financial Geography to be an ind

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

Durant le même temps les problèmes bancaires de chaque jour se classaient d’eux mêmes dans une perspective géographique.Jean Labasse (1955: 1), about his early banking years

Finances in geography

The scope

Financial instruments are fundamentally promises. This can be easily seen by considering the money which we use in our daily life. It contains an implicit promise. A $100 note is understood to be good for buying goods and services worth that much. It is formally backed by a certain amount of gold, or treasury bills and bonds, or the government’s declaration that it is a legal tender. But at closer look, gold does not have too many practical uses, treasury paper is only another type of promise, and government fiat is good only as long as the government has the power to enforce it. Promises are fluid. They can (and hopefully will) be kept, but they can also be broken. The breach can be open, as when the government declares that it will delay interest payment and amortization of its debt. Or it can be disguised, as when it covers a budget deficit by using the printing press and thereby debases the money, with which it later redeems its paper. And still, government the government generally considered a good risk, a baseline from which other risks are calculated. When we know this and realize that a financial system is actually a pile of promises, although organized, we also understand that it can occasionally collapse if left unattended. To call it a house of cards may be too extreme, but it certainly resembles more a bamboo structure than a concrete construction.

Promises are immaterial. They have no physical weight and an amount of $1bn can be transferred as easily as of $1,000. That has created an idea that the friction of distance does not matter, or it matters very little. And when it matters, it is primarily because of the human administrative framework where everything must take place. The importance of that framework is obvious. But it does not follow that if the framework did not exist there would be no friction and that would be, as one provocative author expressed it, ‘the end of geography’. There would be enough friction even thereafter. The most fundamental is the daily rhythm which means that working hours move geographically from east to west with the sun and financial activity with it. The rhythm cannot be rationalized away and its modification is possible only to a degree and at considerable cost – exchange late-hour trading, for example. Another reason is that people’s informational radius is constrained and their ability to digest information possibly even more so. Each kilometre added to the radius means that there will be a disproportional increase in information volume, a simple geometric truth in a uniform landscape. Then there is the cultural dimension, the way things are done ‘here’, made visible in people’s behavioural preferences. It is not easy to convince a German entrepreneur that s/he should disclose internal information for the doubtful benefit of getting the firm listed at an exchange and making it vulnerable to a hostile takeover; or that a Japanese public servant should take away his/her benevolent hand from the company and leave it unprotected to the storms of market forces. When things are so, it is better to accept the facts and admit that geography, indeed, matters. This book will show how in more detail.

Specifically, this book is a general presentation of international financial markets from a geographical angle. For shortness and convenience it is titled Financial Geography. The focus is on the financial community, not on welfare economics. To emphasize this, the subtitle, A Banker’s View is added. The book is intended as a primer for people looking for a career in international business. The career need not be in banking and finances. Rather, the idea is that international finance is an integral part of the education of a modern executive. The liberalization and deregulation of financial systems have made the financial world more volatile and influential than ever before since the Second World War. This also makes it imperative for a future manager and executive in manufacturing, retailing and non-financial services to be familiar with financial basics. That package is traditionally offered by specialized financial classes and the tradition will certainly prevail in the foreseeable future. This dominance does not mean, however, that other disciplines have nothing to contribute.

Mathematics has been a prime example of such a contribution with the creation of modern portfolio theory and the spreading of derivatives trading. Political science puts the daily hurdles and technological advances into a wider context, reflected in country credit ratings, for example. General economics advises on how political priorities can be conciliated with economic realities. Commercial law lays the foundations of regulatory frameworks. Social anthropology sheds light on the selection mechanism of business partners and the cultural clashes arising from mergers and acquisitions. And because everything takes place in a two-dimensional, limited space called the globe, geographers believe that they also have something to contribute.

Financial writing is not commonplace in economic geography. Most geographers are interested in tangible things, and money, in the modern sense, is very intangible. The intangibility easily gives the impression that the friction of distance, the core of geography, will be marginal at best. And when the friction of distance is lost, the discipline also loses most of its foundations. This opinion implicitly assumes that the financial landscape is homogeneous. If it were homogeneous, the logic might hold, but the real financial landscape is not homogeneous at all. It is extremely heterogeneous and full of anomalies. This feature creates flows which otherwise would not exist, and it creates the need to explain.

This book is aimed at the simplest descriptive and explanatory level. It unravels where the financial resources are, describes the actors moving them around, and explains what the underlying infrastructure looks like. It maps markets, their organization, location and clustering into finance centres. The mechanics and terminology of the financial world are explained in some detail for those who are unfamiliar with them. The angle is international and global. National topics are of interest only when they are reflected in the international arena.

Although descriptive, the book is not easy reading. It is full of facts, often detailed facts. Details simply are important. When a $500m issue is placed in thirty minutes, some detail cannot be overlooked. Two per cent reserve requirement at the central bank or 30 per cent withholding tax can have devastating effect. Insisting that a large trade be made public immediately rather than after ninety minutes in a quote-driven exchange means that market makers start deserting the place. The money is in the small print. Details are also an indirect warning against simplistic explanations. The number of banks is a typical case: it is used frequently and very indiscriminately in academic writing as an indicator of a finance centre.

The somewhat monotonous figures easily confuse. That comes from the nature of the topic: it is a description of an entire industry and the comparatively few rich countries operate in a number of guises. But the purpose is not simply to offer a wealth of facts; these get rapidly outdated. This book also helps the reader to look in the right direction for additional information and guidance, and it puts details into a context, gives them perspective and establishes a benchmark against which specialized studies can be projected.

Still more fundamentally, the book promotes geography as a scientific discipline in financial writing. The geographical angle can be conveniently summarized in three slogans:

- spatial differences,

- processes in space,

- spatial interaction.

The setting is familiar, the applications less so. Between-country differences in minimum reserve requirements, assets under management and equity ownership obviously come under the first heading. The expansion and contraction of bank networks, or screen-based continuous auction systems at exchanges and the acceptance of mutual investment funds in various countries typify processes in space. Observed and inferred financial flows between countries, the operation of payment systems, and exchanges offering broadly similar contracts jointly or in competition over extensive areas are all examples of spatial interaction.

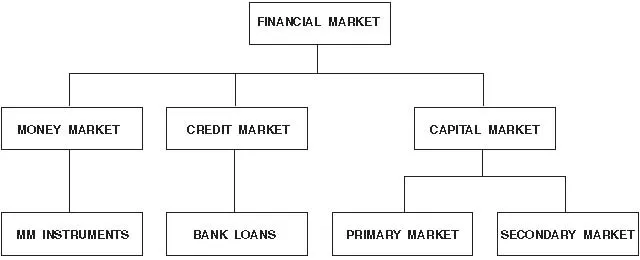

Financial markets comprise money, credit and capital markets (Figure 1.1). Financial instruments with maturities of twelve months and less belong to money markets, while longer maturities split into credit and capital markets. These longer maturities often lead to physical investment. Money markets have got their name from the need of banks to balance books each day by trading short-term financial instruments against cash, and the efforts of the central bank to regulate the monetary stock through the sale and purchase of short-term bills. Credit markets need the intermediation of banks, that is, they are loan markets. Capital markets may benefit from temporary intermediation but basically the contact is direct, between borrowers and lenders. The traditional products are bonds and shares, i.e. securities, which are issued in the primary market and traded in the secondary market. Nowadays they are paralleled by derivatives, which are originally instruments for risk management but which in certain circumstances can substitute securities.

Previous work

Reviewing previous financial research with geographical interest is like travelling an ocean in a row boat. One sees a vast area of water, more from the wave crest than the valley, but one knows that only a very tiny part is within the horizon. Then there is the sky, high and equally without boundaries, with ample space for thoughts to rove and fantasy to gallop. It is where the conceptualizers thrive. This vastness should now be compressed on a few pages into a comprehensive account where everybody who happens to open this volume will find his/her work amply quoted. Such an achievement is impossible and, rather than trying to be comprehensive, this review is selective. From among a very limited array of familiar sources those are quoted which seem relevant for this study and its approach. A conscious effort has been made to ensure that the various aspects would receive a balanced treatment, a feature which need not exist within the available material. There is also another policy, to comment on work which is not published in English. Although English is the undisputed lingua franca of financial writing of our time, everything is not available in it and there is innovative work in other cultures, too.

Figure 1.1 Financial markets.

Source: Die Zürcher Börse, eine Einführung in den Börsenhandel, 1997: 14. Copyright 1997 of Zürcher Börse; used with permission.

A natural starting point is to consider existing reviews about financial writing in geography. Three widely known treatises are available: Corbridge and Thrift (1994), Leyshon (1995; 1997) and Martin (1999). Corbridge and Thrift outline how geopolitics have shaped the financial world, whereas Martin describes the birth of a new subdiscipline. Leyshon adopts a more philosophical attitude which may give a better background for a thoroughly empirical and practical book. The account was published in two parts with a lengthy interval.

In the first part, Leyshon (1995) focuses on political economy approaches and divides the field into geopolitics, geoeconomics and financial exclusion. The geopolitical part penetrates the smokescreens of liberal, egalitarian, socialist, or whatever ideas are routinely used to hide the underlying power politics. It helps in understanding the current financial system and gives hints about its sustainability. Since systemic shifts carry with them grave risks, while also offering unusual opportunities, the prognostic abilities of geopolitics should not be underestimated. Geoeconomics is a step closer to the operational level. The geopolitical situation is accepted and attention turned to investment portfolios, credit flows, preferred currencies and cultural surroundings constraining and shaping basic economic forces. These are topics extensively discussed by economists and financial analysts. Their inclusion in geography may be controversial, although in line with the approach of this book. The final part, financial exclusion, is more familiar ground. It states basically that poor people and poor countries cannot expect financial services on a commercial basis, or at least they are priced higher than otherwise. Where a limited savings generating capability nevertheless exists, grassroot activity leads to self-help in the shape of credit cooperatives and similar. Historically, they are the reborn savings banks and agricultural credit cooperatives, which in some quarters may have lost their roots and become part of the establishment.

The second part (Leyshon 1997) is about multiple monies, monetary networks and finance centres. The section on multiple monies is largely a historical and socioanthropological account of the many shapes which money has taken and the uses to which it has been put. Monetary networks have a heavy philosophical tilt. Although certain geographical properties are quoted, such as the territory in which specific monetary forms may be used, social and anthropological views, again, get the upper hand. The last part about finance centres is more tangible. The perspective continues to be social and cultural, but there is no denying that the persistence of these centres relies heavily on social factors. Then there is the need to build trust, best established through face-to-face contact, which in turn benefits from co-location in the same centre. This is an example of ‘monetary’ networks and specifically an actor-based one. Central bankers, meeting regularly at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) to discuss common regulatory issues, would have been another example.

The prevailing political scene and philosophy is quite fundamental for the financial world and, by extension, financial writing. It is worthwhile, therefore, to be acquainted with it in broad outline. This has been the theme of Helleiner (1993; 1995) and Leyshon and Thrift (1992; 1995a) who, in four admirable articles, map the world after the Second World War, as well as partially covering the interwar period. Helleiner identifies five characteristics for financial dominance: leading creditor controlled by public institutions, banks dominating international markets, prime cities occupying the top slots of financial hierarchy and the national currency playing a global role. The global scene and Japan’s role therein are described with emphasis on euromarkets, the attempts to constrain them and the triumph of rampant financial liberalism in the 1980s. The conflicting interests and power relations of the three major players, the USA, the EU and Japan, are sharply illustrated. Leyshon and Thrift focus on Europe and see its integration as a solution to the collapse of Bretton Woods, a system which either ignored or was unable to control capital formation at multinational corporations. Nor was it constructed to withstand the eroding effect of US monetary expansion because all currencies were ultimately tied to the dollar. The solution to the developing crisis was to create the EMU which also dethroned the deutschmark as the local benchmark currency. That takes us to the role of money as a measure of value, storage of wealth and vehicle of exchange, so elegantly discussed by Cohen (1998), gratifyingly from a geographical perspective. There the issues are the territorial reach of a currency, its possible sharing of sovereignty, its place in the global monetary hierarchy and the gain or loss of power emanating therefrom.

These high-level presentations can then be sharpened by specialized studies, such as Ackrill and Hannah (2001), Chernow (1990), Gall et al. (1995), Karyotis (1999), King (1991), Kynaston (2001), Reid (1988), Robins (1987) and Rogge (1997), to mention only a few. Their actual theme is a bank or a city, not the political background, but they show the interconnection between the operational level and the high politics.

The political game as such would not have created today’s global finances without novel thinking and novel technology. Corresponding accounts are legion and the following are mentioned only to give a taste of the soup. Häusler (2002) looks at how banks have got disintermediated since the mid-1980s, and how they responded by diversifying offerings and expanding geographically. The diversification was greatly facilitated by scientific advances about portfolio theory, market efficiency, risk transformation through derivatives and so on, combined with the revolutionary enhancement of computing capabilities (Huang and Litzenberger 1998). Spatial expansion was speeded up through the development of communication technology, well observed in geographical writing (Code 1991; Hepworth 1991; Kellerman 2002; Langdale 1985). The technology is needed for the distribution of information, trading and the subsequent transfer of money and securities. Trading itself is difficult to observe from the outside but the deals can be registered without too much effort. They have remained in the realm of financial economists because most of the relevant questions have a pronounced time dimension. Where geographers could have made a serious contribution, but have not, is in payment and settlement systems. They are numerous, specialized to a degree, contain a substantial systemic risk and are full of time–space geography. (Davis et al. 1986; Fry et al. 1999; Geiger 1995; Giddy et al. 1993; Heller 1995; Johnson et al. 1998; Laulajainen and Johansson 2000; Lührig and Spremann 1995; Vital 1995)

An immensely popular monograph published a decade ago raised the issue of whether advances in communication technology and the dismantling of regulatory boundaries have made geography, i.e., distance, redundant as an explanatory paradigm (O’Brien 1992). It was a very good question and has catalysed much research. The foremost query then is, what kind and how much regulation? No exhaustive answer can be given but must involve the specific customs of the particular country, including the formal legal system, regulation based on it for banking, currency, exchanges, accounting and so on, and customs of the trade. This framework, and its efficient enforcement, has relevance far beyond financial dealings and may be a condition for economic development at large (de Soto 2001). A lucid introduction with good historical grip is provided by Economides et al. (1986), although at too general a level for practical needs. That shortcoming is amply remedied by the six volumes of international law authored by Wood (Stoakes 1995). The legal systems of the world are divided from financial perspective into seven main groups, six with origins in Europe and Islam’s sharia as the ‘outlier’. The criteria used are security (collateral), insolvency setoff, recognition of trust, notification of debt assignment, veil of incorporation and corporate rehabilitation. The litmus test is their status at bankruptcy (Wood 1995a; 1995b). This is assuring academically but even related legal systems are, in practice, incommensurable. The USA and UK offer a prime example (Stoakes 1999a; 1999b). Euroland may have come furthest in conciliating and consolidating different systems but even it has a long way to go.

Administrative rulings based on existing law logically lag behind the law-making itself (Blumer 1996; Laulajainen 2000; Mikdashi 1998). To speed matters up, interested parties have created their own codes of conduct. The codification of bank capital adequacy under the auspices of the Bank for International Settlements has been epoque-making. It was preceded by accounting rules, supported by professional associations, and sanctioned and promoted by the authorities. International codification is still half-way, which is a constant nuisance to practitioners (Banque de France 2000: 122; Berton 1999; Frankel and Lee 1996; Vortmüller 2001; Waters 1996). Accounting rules are hardly commented on in geographical literature, although they are a keystone of all financial markets. They are reflected in the valuation of companies and their credit ratings, carried further to the international scene when investors compare investment objects in different countries (Laulajainen 1999). Company ratings are constrained by country ratings and here the geographical angle comes prominently to the fore (Chambers 1997; Huhne 1996). The geographical profession has been more interested in describing the structure of international service companies, particularly in accounting and law. (Beaverstock 1996; Daniels et al. 1989; Warf and Wije 1991)

When we approach the financial markets proper, their structure becomes relevant. It is common knowledge that the US and UK financial markets were structured around securities markets some five decades earlier than markets in Europe and Japan. Satisfied with this observation, geographical research has contented itself in discussing the general pros and cons, but not bothered about measurement – with one exception. Yasenovsky (2000a; 2000b; 2000c) has, in three seminal articles, done exactly this. He sees the banking, or financial, culture as an expression of the general development of the country, its habits and traditions (centralization, authoritarianism), moral values (the protection of the small man, for example), globalization (securitization), spread of innovations, historical development (usury rules, for example), and banking legislation (Glass–Steagall, for example). From this he develops a typology based on the role of the central bank, the system’s openness, competitiveness, innovativeness and volatility. The main types are: Anglo-American, with its commercial/investment bank dichotomy; German, with its universal banks; Latin American; Asian conglomerate system; Offshore; and Islamic. When countries are allocated between the types, India and New Zealand end up in the Anglo-American group, whereas Argentina and Australia fall in the German one. China, Japan and Korea form the Asian group and the Latin group comprises only Brazil and Mexico. In other words, there are numerous countries which ar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Playground

- 3 Markets

- 4 Exchanges

- 5 Banking

- 6 Insurance

- 7 Finance Centres

- 8 Outlook

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Financial Geography by Risto Laulajainen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.