![]()

PART I

The political economy of resource nationalism

![]()

2 Trends in minerals, ores and metals prices

Samuel K. Gayi and Janvier D. Nkurunziza1

Introduction

Commodity dependence, defined as the ratio of commodities exports to total merchandise exports, appears to have increased over time. Whereas 64 per cent of countries had a ratio of commodity exports to total merchandise exports of at least 50 per cent in 2009–2010, the proportion of countries with this ratio had increased to 70 per cent by 2012–2013. Out of 133 developing countries2 analysed, 93 countries derived 50 per cent of their merchandise export earnings from commodities in 2009–2010 (UNCTAD 2014a). By 2012–2013, the number of developing countries deriving at least 50 per cent of their merchandise export earnings from commodities had increased to 100. If this cut-off point is increased to at least 80 per cent of merchandise exports derived from commodities, 45 per cent of developing countries under review could be classified as commodity dependent in 2009–2010, increasing to 47 per cent by 2012–2013. The situation in Latin America and the Caribbean region reflects this pattern.

The economics literature has generally associated commodity dependence, a feature characterizing most developing economies, with negative development outcomes. The literature argues that commodities affect development through three main channels: negative terms of trade, the Dutch Disease phenomenon, and political instability often resulting from struggles over the control of rents associated with commodity windfalls (Humphreys et al. 2007; UNCTAD 2013a).

In spite of the negative association between the reliance on commodities and economic development, commodity sectors are of strategic interest not only to resource-rich developing countries but also to other stakeholders including multinational companies and their host countries, which regard them as high-return destinations for their financial capital. On the one hand, commodity exports are the major source of foreign exchange in a number of developing countries in Latin America and Africa. On the other hand, developed countries such as Switzerland, where about 570 companies are involved in commodity trading alone, derive substantial benefits from commodities trade. It has been estimated that commodity trading in Switzerland, for example, has a workforce exceeding 10,000 employees, and represents 3.6 per cent of the country’s GDP. In 2010, commodity trading contributed to about 50 per cent of the country’s economic growth (SwissBanking 2013). Therefore, the way that rents, generated in the commodity sectors, are shared by the different stakeholders along the value chain is an important determinant of the sector’s growth and development, including its stability.

In some ways, resource nationalism may be considered as a response from resource-rich developing countries to the perceived inequitable distribution of the resource rents generated along the commodities value chain. The efforts of this group of countries to obtain what they consider as a ‘fair’ share of the rents generated by natural resource extraction have often been frustrated by TNCs’ tough negotiating stance, derived from a power asymmetry between them and host countries. Resource nationalism has, however, not been limited to resource-rich developing countries. Natural resource-rich developed countries such as Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom have also renegotiated contracts with mining companies controlling the value chains to increase their share of the rents derived from these resources (Bremmer and Johnston 2009).

Resource nationalism comes in different guises: increases of the government’s ownership stake; increases in taxes and royalties, which could be introduced as part of a broader reform in the mining sector; and restrictions on imports and exports3 (Ernst & Young 2013). In its extreme form, the exploitation of a natural resource is nationalized, as was the case in Chile, when the state-owned copper company gradually took over copper operations from private companies starting in 1964, and culminating in full nationalization, ‘estatización’ in 1971 (Léniz n.d.; Meller and Simpasa 2011).

In general, resource nationalism does not only derive from the need to increase the share of rents accruing to host countries. It is usually underscored by a combination of factors, such as cultural, historical, political, or economic motivations (Domjan and Stone 2010). It has also been argued that rising energy prices underscored by geopolitical and market conditions, could instigate nationalistic resource policies. In this regard, resource nationalism is identified as a cyclical phenomenon, the intensity of which ‘…is felt far more acutely at the upper end of the resource cycle than at the lower end when it begins’ (Maniruzzaman 2009: 81). Indeed, the recent rise in resource nationalism seems to have coincided in the last decade or so with the longest commodity boom across virtually all commodity groups. In its update on resource nationalism, Ernst & Young (2013, 2014), for instance, identified a total of 27 resource-rich countries (both developed and developing) that implemented different forms of resource nationalism policies:4 government ownership (7), increases in taxes and royalties (2), restrictions on imports and exports (5), and mining reforms (13).

Historically, commodity markets have been characterized by boom and bust cycles; thus the size of resource rents fluctuates with commodity price fluctuations. During periods of high prices, investors pour their resources into the production and trading of commodities as they anticipate high returns. At the same time, depending on the terms of the contracts binding investors and resource-rich countries, high commodities prices should be associated with higher export earnings for the exporting country. Low prices, on the other hand, may result in disinvestment and shrinking resources in producing countries. It has been established that many resource-rich countries engage in costly investment programmes, often with low returns, during boom periods (Bevan et al. 1993; Hirschman 1977).

When prices decline, countries are unable to maintain the same consumption and investment patterns. Hence, they either abandon their projects or borrow to complete them, sometimes driving their debt stocks to unsustainable levels as a result. Thus, booms and busts in commodity markets have had a substantial effect on macro-economic performance of resource-rich developing countries. The long-term downward trends in commodity prices observed during the 1980s and 1990s negatively affected economic performance in many resource-rich developing or least-developed countries (Deaton 1999). Therefore, understanding the general trends in commodity prices can help shed some light on the behaviour of resource-rich countries with respect to the management of their commodities sectors, including, where relevant, the occurrence of resource nationalism.

This chapter analyses the general trends in commodity prices since the 1970s, with a particular focus on minerals, ores and metals. It provides background information that could help to understand why countries, particularly in Latin America, resorted to resource nationalism policies at some specific period in their commodities price cycle. The underlying question, even though this chapter will not attempt to address it, is whether high commodity prices, particularly those observed since the 2000s, might have contributed to motivating some producing countries to adopt resource nationalism policies, allowing them to capture more of their natural resource rents. Retaining value locally, in order to increase the share of commodity rents accruing to them, remains a challenge facing most commodity-dependent developing countries.

The rest of the chapter proceeds as follows. The second section reviews the trends in global metals markets, identifying some of the major driving factors. The third section analyses the interaction between commodities prices and some key macro-economic variables. The cases of 3 mineral-rich countries in Latin America are used as an illustration. The fourth section concludes.

Global metals markets: an overview since the 1970s

Since the 1970s, commodity markets have been characterized by price cycles with higher fluctuations than in preceding decades (Chu and Morrison 1984). Such cycles have usually seen shorter boom periods followed by longer periods of bust (Cashin et al. 2002; UNCTAD 2003), except for the upswing in the 2000s, which has been recorded as the longest in history.

Trend of minerals, ores and metals prices

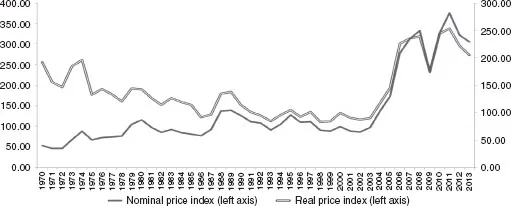

From 1970 to the 2000s, nominal prices of minerals and metals, as depicted by their price index, show a generally upward trend with intermittent fluctuations. However, in real terms, they have trended downwards until the early 2000s (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Nominal and real price indexes of minerals, ores and metals, 1970–2013 (2000=100)

Source: UNCTADStat

Notes: The real price index was obtained by deflating the nominal price index by the unit value index of manufactured goods exported by developed market-economy countries with 2000 as the base year. The manufactured goods included in the index cover: chemicals and related products, manufactured goods classified chiefly by material, machinery and transport equipment and miscellaneous manufactured articles (sections 5 through to 8 of the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC)).

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Minerals, Ores and Metals Price Index,5 in nominal terms, increased by roughly 90 per cent from 1972 to reach 88 points in 1974. This corresponds to a 68 per cent increase in real terms.6 It was not only oil prices that experienced a dramatic increase in 1973–74 but also commodity prices across the board, leading to a major commodity boom. For example, prices of agricultural commodities such as cereals more than tripled over the period 1972–74. Afterward, the index showed relative stability in nominal terms until the early 2000s, save for some short-term fluctuations, particularly during 1979–80, 1988–89, 1995 and 1997 due to various macro-economic shocks. In the early 2000s, dramatic increases in commodity prices ushered in another commodity boom. Between 2003 and 2008, the nominal index for minerals, ores and metals increased more than threefold. The dip in 2009 was the result of the financial crisis but prices recovered quickly to reach their peak in 2011, although they have eased in the last three years. Nevertheless, the nominal index shows that the current prices are still much higher than their levels before the beginning of the commodity boom in 2002.

For most of the period since 1970, the real value of the index trended downwards. From 1974 to 2000, the nominal value of UNCTAD Minerals, Ores and Metals Price Index increased by 13 per cent whereas the unit value index of manufactured goods exported by developed market-economy countries increased by about 122 per cent, leading to a decrease in the real value of the index by 50 per cent. This means the slight upward trend recorded in nominal prices of minerals, ores and metals could not match increasing prices of manufactured products over the same period. This confirms the unfavourable evolution in the terms of trade of countries that export minerals, ores and metals but mostly import manufactured products. The long-term decline in real prices is illustrative of the relevance of the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis, even taking into account the recent commodity boom (Harvey et al. 2010) and the effect of cheap imports from China on the terms of trade (Kaplinsky 2006).

From the end of 2003 to 2004, commodity prices in global markets rose gradually but the pace intensified between 2004 and 2008. For example, the UNCTAD Minerals, Ores and Metal Price Index rose to 137 points in 2004 peaking at 332 points in 2008. Thereafter, the boom was interrupted by the 2008 financial crisis. The price index lost 100 points between 2008 and 2009. However, subsequently, as demand recovered from emerging economies such as China, amid supply constraints, commodities prices rebounded to reach new peaks in 2010 and 2011. Moreover, intensified speculative trading, boosted by low interest rates and weak oversight of financial derivatives transactions, (the so-called ‘financialization of commodities’) amplified upward price movements and increased price volatility. In 2011, the UNCTAD Mineral, Ores and Metal Index reached an historical peak of 375 points. In real terms, minerals and metals prices also recorded significant increases in the 2000s, unlike the trend through the 1980s and 1990s.

The recent boom in commodity markets has been recorded as the longest in the history of commodities prices. It also has been the broadest, as it has affected almost all commodity classes including agricultural, mining and energy commodities. In 2013, commodity prices eased in comparison to their 2011 level but minerals and metals prices remained high compared to their long-term trend. The UNCTAD Minerals, Ores and Metals Index averaged 306 points in 2013, as demand remained strong.

It is worth noting that even as commodity prices dropped, in some cases dramatically, after reaching peaks during upswing periods, they have not returned to their pre-boom levels. It would, however, be simplistic to conclude that current levels of prices are likely to be a new phase of minerals, ores and metals prices. As highlighted by UNCTAD in its 2013 Trade and Development Report (2013b: 59–60) there are differing views. First, one school of thought contends that we have actually entered in a new phase of calmer and more stable growth where commodity prices will remain at relatively high levels compared to their pre-2003 levels. For these observers, the pre-2003 levels of commodity prices are behind us. Second, some observers think that the expansionary phase of the commodity supercycle, started a decade ago, still has some years to run. This school of thought argues that emerging economies including China and India will continue an intensive growth trajectory that will keep commodity prices firm. Finally, some others believe that the expansionary phase has come to an end and further price drops should be expected. The ongoing restructuring of China’s economy, which to some extent is shifting from investment to consumption, may sustain this point.

The main drivers of minerals, ores and metals price trends

Several factors explain the general trend in the price index of minerals, ores and metals. The most important drivers relate to ‘fundamentals’, or demand and supply factors. Other factors include macro-economic policy stances in developed economies, most particularly US monetary policy, as well as financialization of commodities.

Effect of economic fundamentals on the prices or minerals, ores and metals

Minerals, ores and metals have specific properties that make them valuable for industrial use. These properties include high strength, durability, capacity to conduct heat and electricity, use in the manufacturing of mechanical tools, and in infrastructure development. Iron ore, for example, is the primary commodity used for steelmaking. Steel is also known to be used in many industrial and...