1

Facing up to the hurdle race

Jenny Corbett, Anne Daly and Dehne Taylor

Two decades ago the main interest in a comparison of labour markets in Australia and Japan was in the role of national labour market institutions in determining macroeconomic outcomes. Australia was experiencing historically high levels of unemployment and inflation, low growth and poor productivity performance, while the Japanese economy was riding the crest of the wave, with low levels of both unemployment and inflation, strong growth and respectable productivity-though harbingers were already evident of poorer performance to come (Hancock et al. 1984).

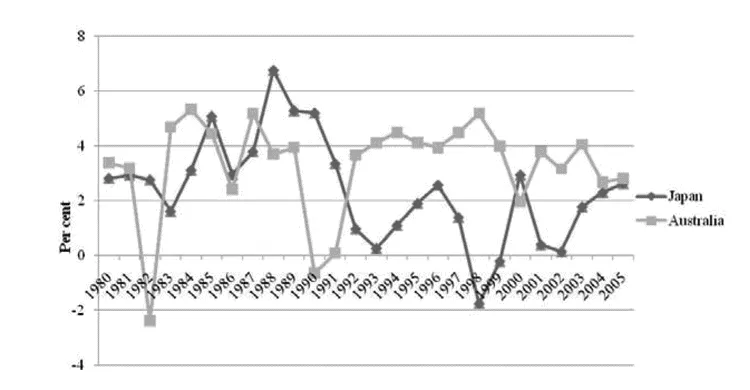

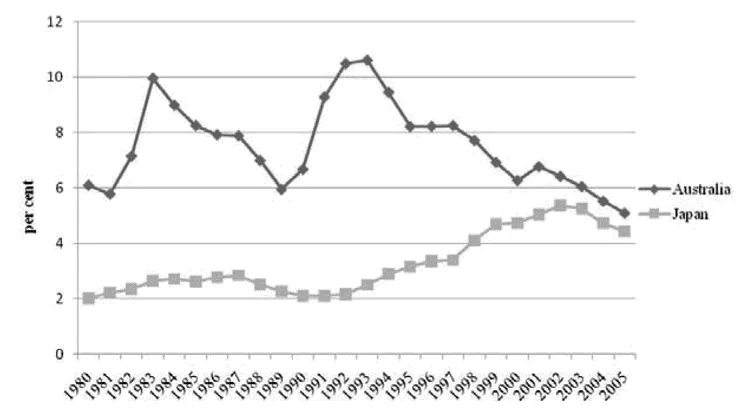

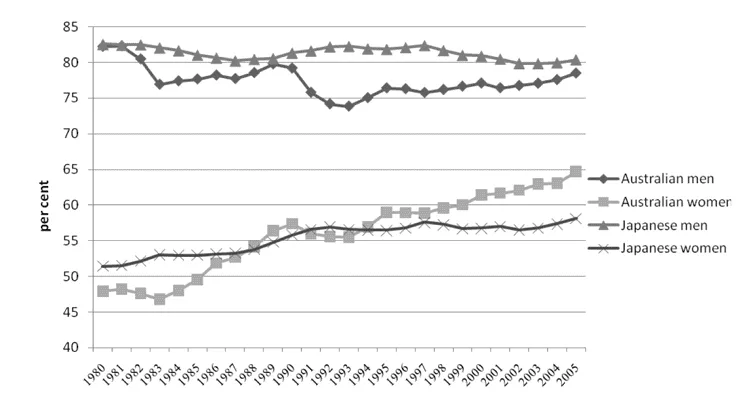

Over the intervening decades Australia and Japan have had contrasting economic experiences. As Figure 1.1 shows, Japan experienced strong economic growth during the 1980s but the economy stagnated in the 1990s, recovering slowly in the first part of this century. In contrast, Australia experienced positive growth each year after 1991. The story in the labour market reflected these outcomes (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3 and Chapter 2 for details). While the Australian unemployment rate fell over the 1990s, the Japanese rate rose and in the first part of this decade they appeared to be converging. The participation rate of working-

age men in the Australian labour force declined in the early 1980s but started to grow again after 1993. Labour force participation of Australian women showed strong growth throughout the period. In Japan, the male participation rate fell after 1990 and only started to rise again in 2000. The participation rate of Japanese women has also grown steadily since the early 1990s.

Over this same period the labour markets in both countries have changed. Australian labour markets have undergone a substantial and rapid change—but not in the direction of the Japanese model of 20 years ago. Instead, Australia adopted policies that were primarily based upon lessons from cross-country research emanating from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). At the end of 2008, the situation between the labour markets in the two countries is almost the reverse of two decades earlier. Australian performance looks impressive compared with all OECD economies, while Japan apparently languishes in a low-productivity, rigid-labour-market trap.

The marked improvement in Australian labour market outcomes over recent years is a consequence of long-term and comprehensive reforms, as described further in Chapter 2 by Taylor, along with growth in international demand for Australia’s exports. Australia’s 2008 unemployment rate was around its lowest level in 30 years. It is also below that of many other members of the OECD and has been below the OECD average for most of the twenty-first century. In contrast, over the 1980s and in the first half of the 1990s, Australia’s unemployment rate was, at times, well above the OECD average rate and significantly above that of Japan (OECD 2006a). The Australian reforms have generally been diverse and broad-based and have improved the microeconomic efficiency of many sectors of the Australian economy, in addition to the labour market. As noted by Taylor, many of the reform processes, and in particular those in the labour market, have been informed by OECD cross-country research such as the 1994 OECD Jobs Study (OECD 1994) and the related OECD report Going for Growth (OECD 2007). Since Australia was able to successfully adopt, and indeed become a model for, much of OECD best practice, Australia’s labour market experiences over this period are now of interest for other nations concerned with improving their labour market outcomes.

Japan’s labour market has been struggling with structural change for a decade (Blomstrom et al. 2003). The Japanese labour market institutions that had been given significant credit for Japan’s prosperous post-war economic growth (‘lifetime employment’, seniority wages and enterprise unionism) have become the subject of growing debate as to their appropriateness for coping with the prolonged economic slowdown since the 1990s and the competitive positioning of Japan’s companies in the twenty-first century (see, for example, Genda and Rebick 2000). Now Japan faces ‘rising labour market dualism, weak productivity growth in non-manufacturing sectors, increased income inequality, low female labour force participation and a low fertility rate’ (OECD 2008a: 186). Furthermore, despite much legislative activity in the field of labour, the outcome to date has resulted in not a single, more flexible labour market but rather the creation of a two-tier labour market which sees a large majority of women and youth facing atypical employment outcomes that are casual in nature and involve significantly lower wages (Rebick 2005).

Despite the differences there also remain many common challenges faced by both countries. Both Japan and Australia face ageing populations—though the problem is more acute in Japan—and some level of skills shortage or jobs mismatch. And policy makers in both countries are concerned with increasing labour market ‘flexibility’ in order to improve productivity in their respective economies. Australia may be facing the end of the easy phase of productivity growth and be entering a period more like the challenging Japanese one.

Macroeconomics, labour markets and productivity

Macroeconomic policies have a strong impact upon the state of the labour market. In Australia, structural reforms have coincided in recent years with the adoption of a transparent, medium-term framework for the setting of both fiscal and monetary policy. Australia’s experience suggests that, in broad terms, sequencing matters. A macroeconomic policy framework that delivers a degree of stability and transparency, together with product market reform based on a robust competition policy regime and liberalization of trade policy, appear to be prerequisites for good labour market outcomes. The Australian experience also offers support for the view that there is a feedback mechanism operating whereby flexible labour markets assist in promoting macroeconomic stability.

Japan reinforces the same message but in the opposite direction. During the decade of the 1990s macroeconomic policy appeared ineffective in kick-starting growth and did not provide that stable and transparent framework that could support structural reform. Despite central bank independence, the credibility of monetary policy suffered serious setbacks; not because of lack of inflation control but because of the opposite. The Bank of Japan proved unable (or unwilling) to stop persistent deflation and maintained inappropriately tight monetary policy until the end of the 1990s. During that period the bank also frequently argued in public that policy was ineffective in the face of a liquidity trap, thereby creating the continuing expectation of falling prices. This proved one factor in the lack of consumer and investor confidence. One curiosity of this behaviour was the apparent fear on the part of the bank that, if prices began to rise, it would be unable to hold them to acceptable rates of inflation. Such a fear might be understandable in a central bank that faced an aggressive wage-setting environment where even modest price rises might be met by strong demands for wage increases, but this could hardly be further from the situation in Japan.

Part of the explanation for different macroeconomic outcomes lies in wage-setting institutions. In an influential article, Calmfors and Driffil (1988) compared employment-related outcomes for countries grouped according to the degree of centralization of their wage determination processes for the period 1974–85. They concluded that countries at either end of the spectrum, with either a decentralized or highly centralized system of wage determination, performed best. It was the countries in the middle, including Australia, that performed worst on employment-related indicators. Japan was included among the decentralized economies—along with countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada—although other research contested that classification, putting Japan at the centralized end of the spectrum because of the co-ordinated annual wage-bargaining pattern (Soskice 1990). It was argued that the good outcomes associated with centralization reflected the fact that peak bodies of employers and employees took into account the negative externalities associated with large wage increases beyond productivity increases in their bargaining. The internalization of this externality constrained wage increases. At the decentralized end of the spectrum, wages were kept down by competition between firms reducing rents.

These findings have been contested in the literature and have been shown to be fragile with respect to the choice of sample countries and the time period (Flanagan 1999). There is some evidence that the greater international openness of many OECD countries over the 1980s and 1990s reduced the importance of national institutional structures. More recently, the OECD (2006a) concluded that there was evidence to support the hypothesis that centralized systems were associated with lower unemployment but they conceded that very similar institutions could be related to different employment outcomes depending on the political and economic contexts in which they worked.

The OECD (2006a) compared labour market institutions of member countries in terms of centralization and co-ordination for three periods: 1970–74, 1985–89 and 1995–2000. Australia was one of the countries that showed the largest change in its score for centralization and co-ordination. Other countries where there were also substantial changes were Denmark, New Zealand and Spain. According to the OECD assessment, Australia moved its degree of centralization of wage determination from an industry-based bargaining structure with some central-level agreements during the early period until 1985–89, to a combination of industry- and company/plant-level agreements by 1995–2000. The co-ordination of bargaining also decreased over the period. In contrast, Japan was rated as having a decentralized process throughout the three periods which remained informally co-ordinated by peak bodies. Table 1.1 reproduces this OECD table. The OECD argued in this report that more reform in general was associated with better labour market outcomes (OECD 2006a).

The ultimate objective of both macroeconomic stability and microeconomic reform is the growth and productivity performance of the economy, and the challenges facing the labour markets that are detailed in the rest of this volume are important not only because of their current impact on labour market outcomes, but also because of their implications for the longer-run productivity of both economies.

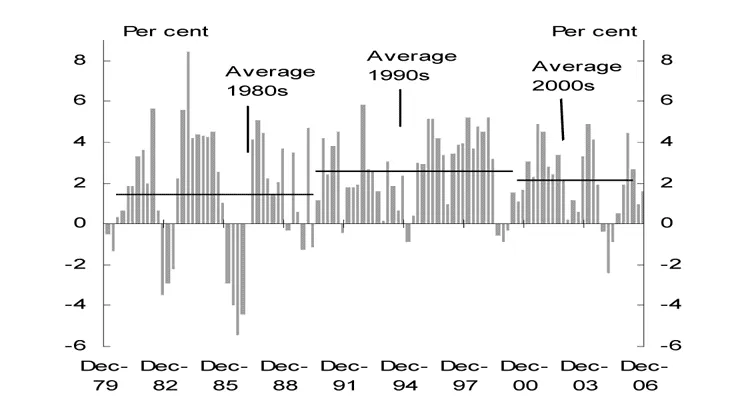

The significance of diverging productivity performance between the two economies is illustrated in many ways. For Australia, productivity in the market sector1 of the economy (Figure 1.4) provides a more accurate indication of aggregate productivity than productivity of the whole economy because output in the market sector can be reasonably well measured by market transactions, independent of the use of inputs.2 Furthermore, the market sector covers around 60 per cent of the Australian economy.

Although labour productivity has grown more slowly since the end of the 1990s, the average rate of growth over recent years remains around the 30-year average (Figure 1.4). The broad and deep programme of structural reform over the last decade contributed to the unusual productivity surge of the late 1990s. Labour productivity growth slowed after 2003–04 reflecting, in part, several special factors, notably the long drought of the early 2000s, the higher employment related to the mining boom, and the labour-deepening effect of incorporating low-productivity workers into the labour force. However, it also probably reflected a slowing of the reform agenda over this period.

Table 1.1 OECD summary indicators for bargaining centralisationa and co-ordinationb since 1970

Recent productivity trends in other countries

The labour productivity (real GDP per hour worked) slowdown in Australia since 2000 is not an isolated case. Around the globe, other major industrial nations have experienced a productivity slowdown since 2000 relative to the United States (Figure 1.5). Much of this story in the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century was due to the recovery of US productivity while other countries failed to keep pace. What is striking is that Japan has remained at low levels of relative productivity, with little change, over nearly 15 years.

The flat productivity performance in Japan is related to some longer-term, and deep, structural problems in the economy. Neither increases in capital stock nor improvements in productivity have been able to offset the negativ...