![]()

1

Introduction

A comprehensive examination of Japan’s aid

Japan was the first non-Western aid recipient to break through the poverty and middle income traps that have bound developing countries around the world to the realm of lower living standards and the human misery that often comes with it. Even before achieving advanced nation status, however, it initiated efforts to provide economic assistance to other developing countries. The scale of this assistance expanded as the country’s level of development advanced until the point where it became the world’s largest donor for almost a decade. The role that Japan’s aid has played in the political economic history of the nation in the post-war era is immense and varied. While there are several studies that have examined Japan’s aid in terms of its practice and policy, the intention here is to examine the numerous dimensions of Japan’s aid and how it impacted the political and economic situation and relationships of the country and of its aid recipients: in other words, to provide a comprehensive examination of Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA). Methodologically this is done both by documenting the history and evolution of Japan’s aid philosophy and practices and by empirically verifying observed impacts through econometric testing.

More than perhaps any other nation, ODA is Japan’s primary international policy tool. As such, Japan’s international cooperation and image is highly intertwined with its ODA policy. A major reason for this is the constitution that Japan adopted which limits its military activities to self-defense. However, this aspect of international cooperation is only one aspect of Japan’s aid policy. The chapters that follow provide a broad inquiry along various angles to see how Japan’s aid can help us understand its own economic success story, the evolution of its political and economic relationships with other donors and its aid recipients, and the impact of its aid on the economies of its recipients. The investigation has broader potential lessons for understanding how aid policy can impact the political dimensions of internal and international relations; how aid could more effectively support economic growth and development; and increase our understanding of the motivations and future impact of the large number of new donors emerging in the world at the beginning of this new century, many of whom appear to be pursuing an aid policy similar to the one Japan utilized in creating its own economic success story.

Three particular aspects of Japan’s aid are the primary avenue of investigation: the internal economic impacts of its aid policies; the effect of the aid policies on managing internal and external political, economic, and diplomatic relationships; and the effect of Japan’s aid in recipient countries. Chapters 2 through 4 take another look at Japan’s remarkable postwar success story. As the first non-Western nation to achieve economic parity with the West, Japan has much to share in terms of expanding our understanding of the development process. Chapter 2 reviews Japan’s development history and highlights important lessons, many of which are taught in economic classrooms around the world in covering the theories on economic growth and development: these include the importance of human capital, investment, and savings. Other lessons that emerge from Japan’s history are less known and, in some cases, more controversial: for example, the role of infrastructure, industrial policy, and the utilization of ODA to generate exports. Japan has often been criticized for conducting a commercially oriented ODA policy. Implied in the criticism is a sense that the country has benefitted from the commercial nature of its ODA. However, there are few studies that closely examine the role of its ODA policy on its own success story. Chapters 2 through 4 document the importance of an export-oriented growth policy in Japan’s economic success and how ODA played a critical role in helping Japan foster the important export markets.

At the same time, the philosophical foundation for Japan’s ODA policy also emerges from its success story as well: an insistence on ODA aimed at promoting economic growth in recipient countries. Japan’s aid in particular supports economic growth through infrastructure development. This is based on its own experience of being an aid recipient and using the monies to rebuild and expand the country’s infrastructure after World War II. Japan also relies heavily on loans in its aid policy, again reflecting its own experience of borrowing funds as an aid recipient and, as a result, taking full ownership to use the aid productively. Japan has stubbornly maintained this primary focus in its aid philosophy over the years despite receiving criticism from other donors. Japan’s initial efforts in aid were compelled as it was required to make war reparation payments to countries in the region who suffered from wartime atrocities. It, however, expanded ODA well beyond these amounts in future years as it saw the benefits of ODA in helping to generate export markets, conduct resource diplomacy with important partners that provided necessary raw materials, and in managing international political relationships both with recipients and other major donors. In many cases we are now observing similar experiences to what Japan went through in many of the new donor nations around the world, including the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). While traditional donors often criticize the aid practices of these new donors, the latter argue for the potential of a win-win relationship in their aid delivery, something they have come to refer to as mutual benefit. By examining the role of Japan’s ODA in achieving its own economic success, the early chapters of the book can be viewed as an initial effort into examining the claim of this win-win relationship in ODA from the donor’s perspective.

Chapter 4 looks at several case studies of Japan’s aid to select recipient countries in Asia. The case studies highlight the relationship between Japan’s ODA and exports to the countries, but also highlight the varied political economic relationships in each case. This is the second major focus on Japan’s aid, the impact on internal and external political economic relationships of the country. While Japan has stubbornly implemented its aid policy based on its belief of supporting aid recipient efforts in industrialization through infrastructure development, its policy has also adapted over the last 50-plus years in response to the evolving aid discourse, which is often reflective of international developments and an increasing realization of the lack of effectiveness of development assistance. Chapter 5 looks at how Japan’s aid policy has evolved in this international reality, where a middle path approach has emerged where Japan has embraced some aspects of the new aid discourse, but also maintained its traditional growth promotion objective in delivering economic assistance. A large reason that Japan has moved in this direction is political in nature, both due to changing circumstances internally and externally, and due to its desire to increase its image and standing in the international arena. Chapter 6 looks through a slightly different lens by investigating the effect of Japan’s aid on the sentiment that nations have toward the Japanese government. This is especially relevant given the historical negative sentiment toward Japan as a result of World War II.

Chapter 7 examines the third and final major theme: the impact of Japan’s aid in recipient countries. In the case of Japan, several of its main aid recipients have reached levels of economic development far surpassing other developing nations. Many of these recipients express outward gratitude and admiration for the economic support Japan has provided. The chapter looks at whether Japan has been successful in accomplishing its own stated goal of generating economic growth in aid-recipient countries. Here, as in previous chapters, every effort is made to compare Japan’s case with other donors. Using panel time series methods, three samples of countries are examined econometrically to test for the effect. In every case there is robust evidence for the positive growth impacts of Japan’s aid: this positive growth impact in addition to the empirical evidence of ODA supporting Japan’s export promotion supports the argument of the mutual benefit of aid, this time from the recipient’s perspective. The results for Japan in the chapter lie in contrast to those found for other donors and multilateral institutions, in some cases. If generating economic growth is the objective of aid, then it appears Japan is doing something right.

Chapter 8 concludes by looking at the possible implications of the lessons learned from Japan’s aid. New donor aid patterns and motivations are studied to see if they follow Japan’s patterns in the past. Also, the relationship between economic growth and poverty across developing countries is examined. Japan has often been criticized for not supporting the poverty reduction focus of other donors. Japan has responded claiming that the best means of lowering poverty is by generating economic growth. Chapter 7 gives evidence that Japan’s first claim that its aid generates economic growth in recipient countries is confirmed. As poverty data has become more widely available for a wider set of countries over the last several decades, a simple empirical test of the second claim on the relationship between economic growth and poverty reduction is supported by evidence of a strong association between the two.

The year 2015 marks the target date of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). For 15 years the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and other donors have pursued aid with the focus of achieving the targets of the MDGs. While some countries have made great strides in accomplishing the goals, others have been stuck: either in a poverty trap for many least developed countries or a middle-income trap for countries that have been unable to reach advanced nation status. The reality continues that too few countries have shown remarkable success similar to what Japan achieved, despite over 60 years of sustained economic assistance. New agendas will emerge with the post-2015 recap and analysis. Ultimately, the hope is that by providing a different and updated look at Japan’s aid than has been done thus far, some of the evidence and lessons from Japan’s experience will spark new insight and ideas for making aid in the world truly more effective.

![]()

2

Japan’s remarkable catch up and the founding principles of its ODA policy

The chapter investigates the remarkable catch up story of Japan, which for all practical purposes began in earnest with the Meiji Restoration. The government’s strong hand in the development process and the importance of human and physical capital development, including infrastructure development, all played critical roles in this catch up. An export-driven growth strategy was also an important feature of the success story and it is here where ODA played an important part in opening and maintaining export markets for the industrial products that drove Japan’s growth. At the same time, this firsthand experience in achieving advanced nation status would provide the foundational principles of how Japan conducts its aid policy.

When catch up occurred

Following World War II Japan faced the awesome task of reconstruction after experiencing the devastation the war left on the country’s economic operations and infrastructure. Prior to the war Japan had gone through a modernization phase during the Meiji Restoration from 1868 to 1912. This was the period that led to Japan emerging as a modernized nation in the 20th century. An excellent account of the economic, political, and social transformation the country went through is provided by Teranishi (2005). During the Tokugawa era travel throughout the country was heavily controlled and it was only in the Meiji era that major infrastructure development occurred in transportation, including railway, roads, and shipping, and in communication, particularly the spread of mail, telegraph, and eventually the telephone, that led to the integration of the country’s various regions (Ibid., pp. 80–83).

In the area of education human capital development increased significantly with eventually over 90 percent of eligible students attending and completing primary school and significant increases in the number of middle and high school buildings (Ibid., pp. 107–11). The expansion of education included increases in more advanced schools that were important for the supply of company managers and educated government officials (Ibid.). In terms of sectoral developments, the increased infrastructure and educated labor force led to increased industrialization with gradual movement of labor into the industrial sector with industry accounting for a greater fraction of overall output and employment in the economy (Ibid., pp. 11–14). The increasing productivity in agriculture and the process of industrialization were important drivers for the modernization of the country and the early 1930s saw the process increase as the country prepared for war with the Sino-Japanese war from 1937–41 and World War II in 1941 (Ibid., pp. 166–71). With the end of the war, while the country’s businesses were bankrupt and much of the infrastructure was damaged, the bureaucrats who were experienced in managing and guiding economic development based on past experiences were still present and in control and they began to exert their influence in the coming years directing the reconstruction and economic catch up effort that the country embarked on (Ibid., 174–75).

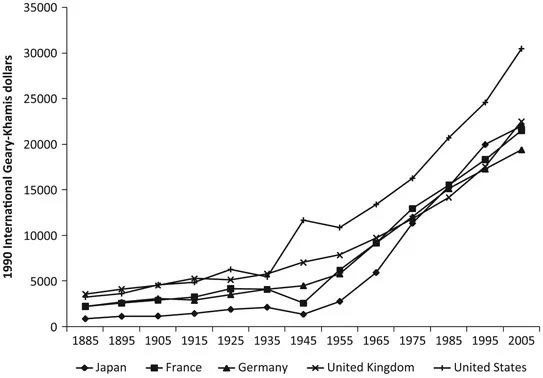

Figure 2.1 GDP per capita Japan, France, Germany, UK, and US, 1885–2005

Figure 2.1 shows per capita GDP for Japan compared to other advanced Western nations. During the Meiji era Japan was on a similar trend line for growth as the Western nations were but was several thousand dollars below in actual per capita levels. The war had large negative impacts on living standards in Japan and France and placed both countries in a sizeable deficit compared to the US, Germany, and the UK. France was quickly able to catch up to par with Germany at the levels that it had exhibited prior to the war, and all countries embarked on a new, higher-trend growth line as can be seen by the post-1945 acceleration across all countries in terms of the slope in the GDP per capita trajectories. Most surprisingly, however, in the midst of this overall acceleration, Japan was able to grow even more rapidly and achieve equal status with France, Germany, and the UK by the late 1970s, achieving a remarkable catch up not exhibited by any other country during the same period.

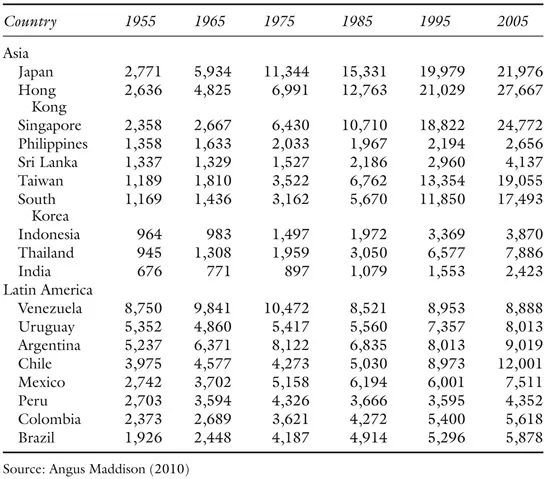

Data in table 2.1 gives comparisons of GDP per capita in Japan and other countries that would be classified in the developing world in Asia and Latin America at the end of the war. In Asia Japan is among the top rank income level countries, but in Latin America it would only rank mid-pack among the group. In Asia, despite being at nearly equal levels as Hong Kong and Singapore, Japan would grow so fast as to have nearly double the standards of living compared to the two countries two decades later in 1975. In the same time span, Japan would achieve higher income per capita levels than any other Latin American country, despite having only half the income level as several Latin American nations in 1955. Following the period of catch up, Japan maintained its status relative to other advanced nations on into the new century based on its sustained growth. Several other East Asian nations would follow in accomplishing this feat, starting first with Hong Kong and Singapore, and then shortly later by Taiwan and Korea. Japan, however, set the example which these and other nations have tried to emulate and duplicate. No Latin American nation has been able to achieve this.

Table 2.1 GDP per capita, Asian and Latin American countries, 1955–2005 (1990 International Geary-Khamis dollars)

The Japanese miracle has been researched and written about extensively by researchers around the globe. There is somewhat of a consensus on varying features of the catch up experience that made the outcome possible. These features are examined here to better understand the important ingredients in achieving economic development, which is the primary overarching ob...