eBook - ePub

Trade and Investment in China

Jim Slater, Roger Strange, Limin Wang, Jim Slater, Roger Strange, Limin Wang

This is a test

Share book

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Trade and Investment in China

Jim Slater, Roger Strange, Limin Wang, Jim Slater, Roger Strange, Limin Wang

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

China is under close scrutiny both as a market that could provide massive returns to investors and because of its potential to become the most powerful economy in Asia. This new study examines the economic relationship between China and Europe, its importance and how it is likely to evolve.

The book considers the flow of trade, direct investment and technology transfer and contains case studies of manufacturing industries (automobiles, toys, watches, telecommunications) banking and insurance. The trade relationship between Europe and China is being re-evaluated by both sides and this is a valuable contribution to that process.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Trade and Investment in China an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Trade and Investment in China by Jim Slater, Roger Strange, Limin Wang, Jim Slater, Roger Strange, Limin Wang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Trade and investment in China

Roger Strange

INTRODUCTION

The past decade has witnessed many momentous events and far-reaching developments in the world economy. There has been the successful, if belated, conclusion of the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations in December 1993. The Round—the eighth and final to be held under the aegis of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)—involved many developing countries for the first time. It resulted in a wide range of agreements—including one on textiles and clothing to replace the Multi-Fibre Agreement (MFA)—which were to be implemented from 1 January 1995. It also established a permanent body, the World Trade Organization (WTO), to oversee world trade in the future. There has been a proliferation of regional trading agreements of varying degrees of scope and ambition,1 not only in Europe but also in North America, Central America, South America, Australasia, and Asia. The disintegration of the former Soviet Union, the reunification of Germany in October 1989, and the fall of the communist regimes in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania have redrawn the political and economic map in Eastern Europe. Asia has become the most dynamic economic region in the world, although debate still continues over the reasons for the ‘East Asian Miracle’ (World Bank 1993) and over the role of trade and inward investment.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has emerged as a major form of economic linkage not only between developed economies, but also between the developed and the developing economies. This emergence may be attributed to five major stimuli (Strange 1997). First, there has been a phenomenal expansion of FDI from Japan—initially towards Asia, then towards North America, then towards Europe, and latterly again towards Asia (and particularly towards China)—reflecting the growing internationalisation of the Japanese economy. Second, there have been moves towards regional integration which have given rise not only to greater intra-bloc FDI but also to greater FDI from firms outside the emerging blocs seeking to gain insider status. Third, there has been widespread liberalisation, notably of service industries, in many countries. Fourth, there has been a sea-change in the attitude of many developing countries, notably in South America and East Asia, towards FDI and, in particular, towards FDI as a source of capital, technological know-how, and managerial skills. As technology has become more sophisticated and the importance of tacit knowledge has increased, so too has the popularity of FDI as a vehicle for technology transfer. And fifth, there have been substantial developments in information technology which have not only made existing markets more accessible, but have also enabled the creation of new products and services and the development of new markets.

As the foremost trading bloc and the largest trading entity in the world, the European Community (EC) had a considerable influence on the out-come of the Uruguay Round, has been a significant catalyst in the evolving pattern of regional trading agreements, and is a major source of exports and direct investment to, as well as a major market for imports and direct investment from, the rest of the world. Recent events have reinforced the status of the European Union (EU): the completion of the Single European Market (SEM) in January 1993; the accession of Spain and Portugal (in 1986), and of Austria, Finland and Sweden (in 1995); the entry into force of the Treaty on European Union on 1 November 1993;2 and the conclusion of the Europe Agreements with Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and the Czech and Slovak Republics in 1992–93, to name but a few of the more important developments. Furthermore, the completion of the internal market has also heralded a more communautaire approach to the Community’s relations with third countries.

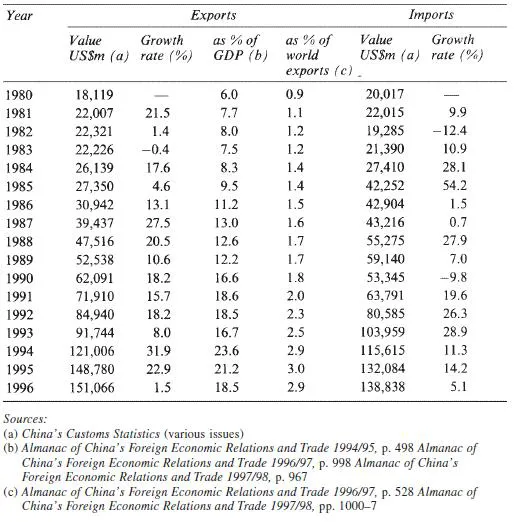

But perhaps the most significant development of all has been the emergence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a significant economic and political power. Since the instigation of its wide-ranging programme of economic reforms in the late 1970s, including the measures adopted to promote foreign trade and investment commonly referred to as the ‘open-door’ policy, the economic performance of China has been startling. Economic growth has averaged about 10 per cent p.a., and GDP per capita has trebled. With a GDP of US$630bn in 1994, China was already the seventh largest economy in the world3and optimistic predictions suggest it might become the largest early in the twenty-first century. Foreign trade has increased dramatically not only in absolute terms, but also in proportion to GDP and to world exports (see Table 1.1). In 1980, China’s exports accounted for 6.0 per cent of GDP and only 0.9 per cent (ranked 27th in the world) of world exports. By 1995, China was a much more open economy with exports accounting for almost one-quarter of GDP, and 3.0 per cent (ranked 11th in the world) of world exports. This impressive growth of China’s foreign trade has been accompanied by major changes in the domestic economy and by substantial inflows of foreign investment, and has been marked by significant changes in the provenance of China’s imports and the destination of her exports. However, as will be discussed below, much of this trade growth has been associated with the establishment of

Table 1.1 China’s external trade, 1980–96

processing and assembly facilities in the southern provinces of China, and the effects upon domestic growth and development may well be relatively minor.

The sheer size of the Chinese economy and its enormous potential as a market have attracted the attention of businessmen, politicians, academics, etc. from all over the world.4 No discussion of trade with China, or of direct investment in China, would be complete without a proper appreciation of the role that Hong Kong (HK) has played in China’s ‘open-door’ policy. Indeed, it is perhaps more realistic to refer to the roles that Hong Kong has played: as financier, trading partner, middleman, and facilitator.5 The financier role refers to Hong Kong’s function as a provider of direct investment and foreign loans, and as a centre for loan syndication. The trading partner role refers to Hong Kong’s domestic exports to, and imports retained from China, both in commodities and in services. In addition to this direct trade, however, Hong Kong also plays a vital and increasingly important role as a middleman both in commodities and services trade .6 In commodity trade, Hong Kong functions both as an important entrepôt for China’s indirect trade with the rest of the world and as a vital centre for transhipments. Furthermore, HK firms perform a significant brokerage function in China’s direct trade. And Sung (1991a:26) notes that:

The dominant role of Hong Kong in direct foreign investment also conceals a middleman function. The investments of Taiwan and South Korea in China are concealed through Hong Kong subsidiaries, and multinational companies also like to test the Chinese investment environment through their Hong Kong subsidiaries.

Finally, the facilitator role refers to Hong Kong’s function as a contact point for China with the outside world (and vice versa), as a conduit for market information and technology transfer to China, and as a market and production training ground for Chinese businesses.

This introductory chapter starts with an assessment of the vital middleman role that Hong Kong has played in trade with China, with particular attention given to the outward processing (OP) activities of HK firms. Estimates are provided for the bilateral trade balance between China and the European Union (EU), taking into account entrepôt trade through Hong Kong. The chapter continues with an assessment of the development of FDI in China, and the contribution of European firms to the inflow of investment. The importance of foreign-investment enterprises (FIEs) for China’s trade is highlighted. Finally, the history of China’s application to join the GATT/ WTO is outlined, and suggestions made as to the likely outcome of the negotiations on China’s accession.

THE ROLE OF HONG KONG

Hong Kong has long been an important trading partner for China. Between 1931 and 1938, imports from China accounted for 37 per cent of Hong Kong’s total imports, and the Chinese market accounted for 40 per cent of Hong Kong’s total exports. Four-fifths of the imports, and nine-tenths of the exports represented entrepôt trade, and accounted for 25 per cent and 19 per cent of China’s exports and imports, respectively.7 After World War II, HK exports (domestic and re-export combined) grew dramatically from US$71m in 1948 to US$221m (38 per cent of total Chinese imports) in 1950, stimulated by the Korean War and the closure of major Chinese ports after the 1949 revolution. However, on 18 May 1951, the UN introduced an embargo on the export of strategic commodities to China following the PRC’s entry into the Korean War, and this led to a sharp fall in HK exports to the mainland. Furthermore, the establishment of the People’s Republic presaged a reorientation of China’s trade towards the communist countries, and a reduction in the import of consumer goods. HK exports to China dwindled to insignificant levels through the 1950s, the 1960s and the 1970s. In response, Hong Kong developed its own manufacturing base so as to generate domestic exports with the result that, by 1978, domestic exports accounted for over three-quarters of total HK exports. Re-exports to/from China accounted for a mere 7 per cent of total HK exports.

In contrast, the situation regarding HK imports from China proved remarkably stable. Throughout the 30–year period fro...