![]()

1 Extractive institutions in the Congo

Checks and balances in the longue durée

Andreas Exenberger and Simon Hartmann

1.1 Introduction

The Congo provides an excellent example when studying extractive institutions in the longue durée.1 It is a place full of astonishing contradictions: the Congo assembles an impressive volume and variety of resources, but it is also a place of endangered human survival due to a lack of capabilities to cover basic needs and to massive violence. Statehood has existed for centuries, but political fragmentation has also occurred and continued well into the post-colonial period. World market integration became increasingly influential from the sixteenth century on, bringing additional revenues for kings and traders, but often at the expense of large parts of the population (Exenberger and Hartmann 2008). Later, the Congo became the center-piece of the colonial empire of a small European power, and also a place where the misfortunes of civilizing missions and resource curses were taken to extremes. Finally, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) emerged as one of the largest and most diverse countries of post-colonial Africa, particularly known for authoritarian rule and instability to the point of civil war, state failure, and economic collapse.

In this chapter, we organize our narrative on long-run institutional development in the Congo. Furthermore, we use the concept of path-dependence (North 1994) along with the categories “pre-colonial,” “colonial,” and “post-colonial.” Path-dependence means tracing present and future constraints as imposed by the way human interaction and institutions have played out in the past and evolved over time. Events and decisions in the past limit the scope of present and future choices. This concept is helpful for uncovering historical parallels, repetition of events and developments (albeit in different clothes), similarities in structures, or even continuities. Hence, we agree with Jacques Depelchin:

Economists who treat the colonial period as if it began with the Berlin Conference and had nothing to do with the preceding slave trade create an abstract, artificial historical framework. . . . The matter under discussion is a historical process that has transformed African societies, and that transformation did not start with the Berlin Conference.

(1992: 35)

However, colonization was a serious disruption. Jan Vansina (1990) even calls it the “death of tradition,” consisting of two main drivers: first, the “invention of new structures” by colonial rulers and, second, the experience of everyday life which made people “doubt their own legacies” and “adopt portions of the foreign heritage,” both also influencing post-colonial developments (Vansina 1990: 246–8).

Finally, we focus on mechanisms of checks and balances embedded in political and economic institutions. Greatly simplifying, we refer to three groups: rulers (“the elite”), ruled (“the rest”), and “intermediaries.” By checks and balances we mean institutions limiting the power and constraining the actions of elites and intermediaries, in the form of credible commitments by the elites to the rest or by elite support of perpetually lived organizations (North et al. 2009). They provide incentives for the elite to address the needs of the rest in the form of public goods rather than seeking private rents only. If they are strong, they tend to make life more predictable for the rest and the abuse of power for private interest of the elite and intermediaries more difficult. But if weak, they bias political and economic competition and cooperation by establishing elite monopolies. The position of intermediaries varies, not least with the degree of difference between the elite and the rest (most pronounced maybe in the case of external colonial elites). Consequently, unchecked and unbalanced power is related to extractive institutions (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012; Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003). A long-run view makes particularly good sense in the case of the Congo because pre-colonial checks and balances already existed, usually based on clan, lineage, or property. We argue that late pre-colonial political fragmentation resulted in a weakening of checks and balances and therefore elites and intermediaries (especially at the local level) were barely restrained from bringing tyranny and disorder to the rest; this also eased the transition to colonial extraction and more recently to warlordism.

The chapter is divided into three chronological parts: a pre-colonial history of African trading networks prior to the Stanley expedition, a colonial history encompassing the reign of King Leopold II and subsequently the Belgian state, and a post-colonial history of civil wars and autocracy in the aftermath of 1960. The conclusion stresses paths and parallels in all these periods.2 A final note of clarification: in this chapter, we usually treat the Congo as if it was a rather homogenous place, which it certainly was not, either in time or in space. We deliberately understate these differences to reveal general trends, otherwise probably obscured by the unavoidable conclusion that everything was at least to some degree different in any two places taken into comparison. This holds not only for pre-colonial times when the territory of today's DRC was shared between many fluid political entities and hence differences are most obvious, but also in colonial times when the degree of penetration and practices of administration differed, and in post-colonial times when the east and the west of the country were often hardly connected.

1.2 pre-colonial history: traditional checks and balances

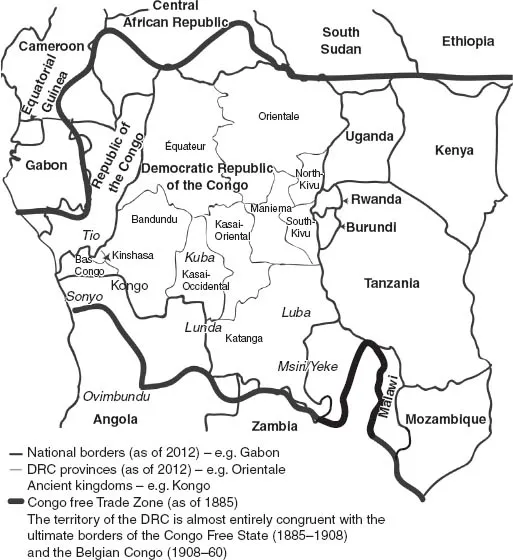

In the nineteenth century West-Central Africa was a multifaceted world with overlapping (social) entities of varying and fluid shape and varying degrees of hierarchy. The most significant of these entities were the Kingdom of Kongo, the Kuba Kingdom, the Luba Empire, the Lunda Commonwealth, and the Tio Kingdom. But there were also other clusters of people and larger social groups (Ngombe, Mongo, Mamvu-Lese, Maniema brotherhoods, and “forest people”). There was a great diversity of institutions among them (centralized or decentralized, broader or smaller power base, etc.). Some adopted institutions inspired by other kingdoms or peoples with whom they exchanged commodities or maintained contacts; for example the Luba state model was adopted by the Lunda. Some did not. The Lele, for example, did not copy the neighboring Bushong (Vansina 1966, 1990; Douglas 1963). Additionally, external actors such as Europeans (from the west) and Arabs (from the north-east and east) had already been present for some time although external penetration of the hinterland remained occasional and weak.

Figure 1.1 Map of Central Africa.

In this environment, slavery (already practised for several centuries) and the ivory trade were economically and politically significant, while subsistence agriculture dominated the economy. Trade in rural surplus production occurred regularly and interacted in diverse ways with long-distance trade all over the region, further deepening in the nineteenth century (Gordon 2009; Vansina 1962). In the Lower Congo (Ekholm-Friedman 1991), archil, copal, gum, ivory, palm oil, and precious woods were traded whereas along the whole river system it was agricultural products, fish, salt, and copper. There was also iron smelting, weaponry and tool production, boat construction, and the production of ceramics, copper rods, pottery, palm and sugar wine, beer, camwood, and cloths (Harms 1981: 46–70; Vansina 1990: 212–13). Copper production, manufacturing, and trade had a long tradition in Katanga, but also in the Lower Congo, because copper was widely appreciated and valuable in art, as currency and prestige good (Herbert 1984: 185–276). Generally, economic links intensified and it was even claimed that the Congo basin was the leading trading zone in nineteenth-century Southern Africa (Zeleza 1993: 421).

In the historical Kingdom of Kongo, the best-known pre-colonial political entity in the region (its heyday was in the sixteenth but it existed until the nineteenth century), a related pattern of power distribution emerged. While rule was generally executed by local kings who were controlled by councils, resulting in “a strong egalitarian component” (Broadhead 1979: 627), the state was nevertheless quite strong. The state played a major role in “the division of land revenue, and no individual, institution or family could establish permanent rights to income through possessing title to rent-bearing land” (Thornton 1984: 160). Instead, income was distributed either by the right to collect the king's revenue from specified areas or by direct grants from the king. Furthermore, we observe important shifts in political order already in the late sixteenth century, including the strengthening of patrilineal descent categories, not least related to Christianity (Hilton 1983; Thornton 1984). Thus, contact with Europeans (starting with Diogo Cão in 1482) had an impact from the beginning via the demand for slave labor from the Americas from the sixteenth century onwards, but also with respect to culture. Coastland actors and societies profited at the expense of the hinterland and some formerly mighty kingdoms became fragile and lost power and population, finally resulting in disintegration (Ekholm 1972; Hilton 1987).

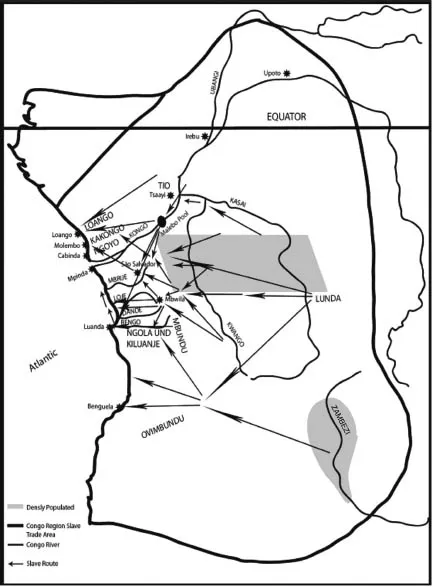

The emerging Atlantic slave trade (Klein 1999; Thornton 1998) had a more significant influence on creating that divergence than intra-African trade, precisely because of the related access to prestige goods. As transactions between Africans and Europeans intensified the area witnessed (see Figure 1.2) more slave raids (increasingly destabilizing hinterland societies through greater violence), a serious disturbance of African labor relations (domestic societies were deprived of a significant part of their productive potential), an inflow of prestigious trade goods exchanged for slaves (considerably influencing domestic power relationships) and of iron tools fostering development (at least in societies with access to foreign markets). In addition to the slave trade's inherently violent character, the demographic losses threatened the existence of kinship groups and entire kingdoms, whose political, social, and economic structures sometimes virtually disappeared (Klein 1999: 125–9). Moreover, slave and slave-holder identities became more fluid on an individual level and slavery-related warfare presented a hazard to security on a societal level. Political power was weakened, challenges intensified, and fragmentation took place including ethnic fractionalization and social alienation (Whatley and Gillezeau 2011). Additionally, this replaced and destroyed legal institutions in Africa, a basis for today's “poor legal environment” (Nunn and Wantchekon 2011). This process of social deterioration gathered pace until well into the nineteenth century as the Atlantic overseas slave trade met with the Arab inland slave trade coming from the north-east (Alpers 1967; Lovejoy 2012); it only came to a halt late in that century when it was finally crowded out by colonial rule.

Figure 1.2 Regional slave trade networks in the Congo Region, 1600s–1800s

In the long term, all this had a very negative impact on development. Furthermore, militarization led to a continuation, if not intensification, of violence in the West-Central African hinterland. This increasingly included food raids, as shown by the destruction of the Lunda Commonwealth by the Lovale and Chokwe aggression in the late nineteenth century (Gann and Duignan 1979: 49) or the decline of the Luba Kingdom, unable to repel armed traders, after 1870 (Wilson 1972: 585–8).

By that time, other “commodities” had already gained importance, especially ivory (Rempel 1998). When global demand for this product expanded, ivory hunters, again including Arabs from the north-east and east, followed the retreating herds to the Central and Eastern African hinterlands (Wilson 1972: 585–6; Vansina 1990: 240–5). In the new business, old trading relations and networks were used (Beachey 1967: 289–90; Gann and Duignan 1979: 117). Like the slave trade, it was “extractive” by definition. The consequence for power patterns was clear: “the definition of chieftaincy revolved around the ability to impose claims for tribute in ivory” (Gordon 2009: 932). Hence, a rising number of guns militarized the hinterlands (Reid 2010). The influence of foreign trade on the allocation of power in the Kingdom of Kongo, for example, is summarized by Susan Broadhead:

Control of foreign trade and the circulation of prestige goods associated with it were at the heart of political power. Possibilities for profit, both economic and political, arose in several areas: control over the movement of caravans in a territory, charges for transit, customs duties and tolls; monopoly rights over products such as slaves, guns, or ivory; privileged access to the market system including information about market conditions; exclusive access to foreign traders; alliances with foreign merchants; and direct participation in trading ventures.

(1979: 637)

Traditionally, societies in the region were based on a distribution of power by vertical hierarchies as well as horizontally integrated groups like lineages, secret societies, cults, or age grades (McIntosh 1999: 4). Therefore, rulers were usually experienced in the use of checks and balances. In the Kingdom of Kongo, committees of local rulers (the “chiefly office”) openly chose and controlled the “councils” (Broadhead 1979: 621). Luba power was balanced not only between landowners and rulers but between the balopwe patrilineages and vidie organizations that had a say in the succession of the rulers ...