![]()

1 Global disparity and environmental sustainability

Introduction

The global economy has embarked on a new phase of growth and development in the new millennium. The current phase of globalisation has had recent beginnings but already signs of its impact have become visible. These are apparent from the trends in income distribution, trade, environmental pollution, and so on. But what is most noticeable about these trends, particularly in relation to environmental degradation, is the extreme disparity on a global scale. We shall discuss these trends in disparity shortly and relate them to the crux of the matter, that is, environmental sustainability.

In a state of such upheaval although all intellectual inquiry has great responsibility, environmental studies have a particularly important onus to understand and anticipate global challenges rather than merely reacting to them. Any serious attempt to study the process of globalisation and its implications for environmental sustainability has to necessarily follow a truly global approach. While such a position might sound tautological, there is grave paradigmatic problem with this fundamental position. A truly global approach has three dimensions to it. It should be global in the sense of including all factors responsible for global environmental degradation (GED). Second, it must transcend space to include all countries of the world. Finally, it should also be truly global in the sense of being concerned with the global interests from the point of view of global environmental management and not just be based on certain sectional interests. To be global in all senses of the term, the first and foremost requirement is to be able to understand the global environmental issues and concerns, in the spirit in which it has been outlined above.

In this context, the paradigmatic problem, referred above, is rather complex. One approach to environmental sustainability decries any method that involves valuation and value judgement in the realm of environmental studies. Further, this approach eschews aggregation across factors of environmental degradation and across countries.1 An alternative approach is based on valuation, value judgement and measurement, but deems the tools of analysis to be inadequate for global studies. Hitherto, the approach has been to study questions of environmental sustainability from the point of view of a region within a country, a country or a group of countries that are similar. More often than not studies have been centred on OECD countries. More often than not this approach equates global environmental concerns with transboundary pollution and ignores other factors such as, water consumption, paper consumption and so on. As a result extant studies have been based on single pollutants, such as, carbon dioxide (CO2) or sulfur dioxide (SO2). With regards to aggregation, this approach considers methods such as forming composite indices to be the preserve of a few.2

Even a casual look at the trends, which we briefly discuss below, would make it clear that it is urgent to overcome such polemics and evolve an overall approach to environmental sustainability. Our ‘Consumption Approach to Environmental Sustainability’ is one such attempt to evolve such a global approach that is all-inclusive in terms of factors as well as countries of the world.

Our study is based on cross-sectional data. The reasons we advance in support of this are as follows. First, it is difficult to get sufficiently long-term data so as to be able to appreciate changes in the global economy. Second, the data sources need to be consistent. These two conditions are not satisfied in practice so, in this study, we have mostly used cross-sectional data from UNDP’s Human Development Report.3 Third, whereas consistent long-term data is available for different groups of countries, like the OECD, such a data source may result in one-sided results since the countries involved are all in a similar phase of development and the necessary global flavour would be lacking. Further, even if such data were available these may conceal global disparities.4 We propose to make it apparent that at the hub of these problems lies global disparity and conflict of interest. For any attempt at global environmental management (GEM) to succeed ab initio it has to reconcile with this given datum. Our intention is not to say that any such attempt at global management is not welcome. Nor is it to say that it would be doomed to failure. On the other hand, we wish to emphasise the urgent need for such a thrust.5

Global trends in development and environment – the carbon sink

Several issues are pertinent to an understanding of global trends in environmental indicators; however, we wish to confine ourselves to some of the most pertinent issues. Many of the factors that affect the global environment are interconnected. Therefore, in the following analysis we shall study these interrelationships from the point of view of understanding the problems in GED and GEM.

In what follows we provide a basic analysis of global trends in three related aspects – forest cover, CO2 emission and paper consumption. While the relationship between them may be amply clear to the aware reader, we would like to reiterate the relationship. Paper of any kind is made from wood pulp. Essentially the demand for paper arises from rich countries and is largely for fine quality paper:6 the finer the paper the higher the grade of wood required and hence the more superior the tree that is to be felled. We may presume that the wood of such trees is much more expensive than ordinary wood and hence its role in nature is much greater. For instance, while local handmade paper is made from bamboo, high-quality paper is made from pinewood.7 The choice that developing countries face is to earn by exporting such superior wood and augmenting growth and incomes domestically or preserving the forests and remaining poor. Needless to say this is apparently an individual choice being exercised by some poor countries but has a global implication for environmental sustainability. Pine trees have a great capacity to absorb CO2 and act as a ‘carbon sink’ than bamboo trees. Such carbon sinks are the only insurance against global warming being caused by ‘green-house gases (GHGs)’, like CO2, that destroy the ozone layer. By felling such forests these countries benefit themselves and by retaining forests the world benefits, at large, and they lose.

From a global point of view the question is: who owns the ‘carbon sink’? Who is responsible for CO2 emission and who really needs these forests? The global trends in CO2 emission, paper consumption and forest cover may answer this question.

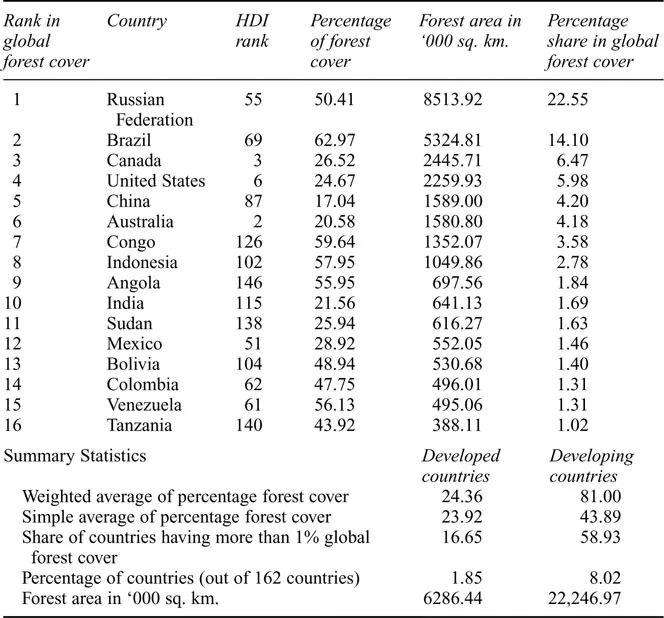

Table 1.1 shows the status of global forest cover in 1999. Since the data relates to Human Development Report we have also indicated the HDI8 Ranks. It is interesting to note that this index conceals the fact that high-ranking (highly developed) countries do not contribute much to green cover. So the index takes into account economic and social criteria but not environmental criteria. The top 48 countries, that is, 30 per cent of per cent of all countries possess only 23 per cent of the cover. Out of these three countries – USA, Canada and Australia, that is 1.85 per cent of the total number of countries – have 16.65 per cent and the rest of the 28 per cent have less than 13 per cent of the global cover. In the case of medium development countries (48 per cent of all countries) they have 67 per cent of the forest cover, in the world. The low development countries form 22 per cent of all countries and have only 10 per cent of the cover. But they are also not yet gainers from development and globalisation.

Table 1.1 Countries whose share is more than 1 per cent of global forest cover (1999)

Source: Based on Human Development Report 1999 and 2000, UNDP, New York.

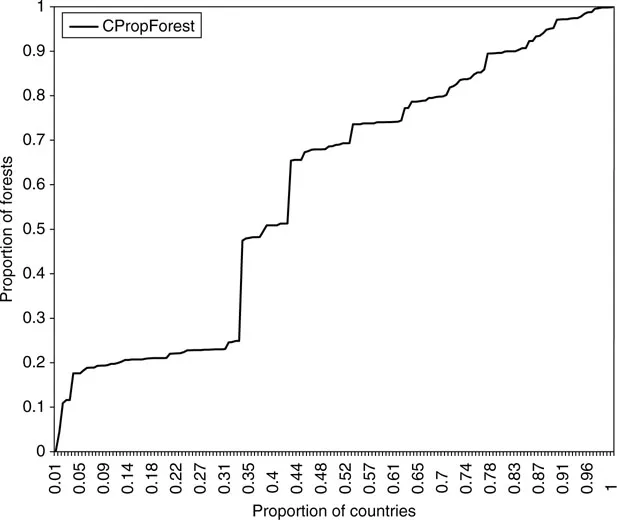

Sixteen countries possess significant forest cover. (We define any country that contributes more than one per cent to the total forest cover in the world as having ‘significant cover’.) Of theses only three countries USA, Canada and Australia are developed countries. The rest 13 are all developing countries. The greatest single contributor is the Russian Federation, which has a 22.55 per cent share in global, forest cover. The smallest is Tanzania with around 1 per cent share. The three rich countries have an average forest cover (out of their total land area) of less than 24 per cent. The same proportion when calculated as a weighted average9 goes up by a few points. On the other hand, the 13 developing countries have simple average cover (within their country) of about 44 per cent and as a weighted average their cover is 81 per cent! The share of these 13 developing countries in the global cover is almost 59 per cent! Hence, the major carbon sink is possessed by developing countries. Devoid of this cover the globe would be at the brink of disaster (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Global distribution of forest cover.

Source: Based on Human Development Report 1999 and 2000, UNDP, New York.

The forest cover in many of the developed countries has evolved out of reforestation efforts. This raises the question of the quality of forests. First, the new varieties of trees are often not suitable to the habitat.10 Second, it has been established that tree plantations host about 90 per cent fewer species than the forests that preceded them. (Allen Hershkowitz, Bronx Ecology, 2002 p. 75), thus reducing biodiversity. Moreover, such monoculture makes the breed of the vegetation more susceptible to disease.

The counterparts of forest cover are paper consumption and CO2 emission. Of the total paper consumed annually, in the world, in per capita terms, 86.75 per cent is consumed by 45 rich countries, which is just 25 per cent of all the countries in the world. On the other hand, 20 per cent of the world’s countries or 35 poorest countries consume only 0.25 per cent of paper. Ninety-four developing countries amounting to 55 per cent of all countries consume the rest, that is, 13 per cent. The per capita paper consumption in developed countries is nearly 60 kilograms. In medium development countries it is around 4 kilograms and in the case of poor countries it is just 0.22 kilograms.

The maximum consumption could go up to 240 kilos in the rich countries! The modal consumption level in rich countries is 115 kilos. The mode in poor countries is 0.1 kilo. These trends are further laid out in Table 1.2 and Figure 1.2. The third component of the environmental trinity we study is CO2 emission. To study this aspect we consider three measures based on Human Development Report 1999:

Table 1.2 Snapshot: paper and the environment

• Of the global wood harvest for ‘industrial uses’ (everything but fuel wood) 42% goes to paper production. (Abromovitz and Mattoon, Worldwatch Paper: Paper Cuts, p. 20, 1999) • Of the 42% of the world’s industrial wood harvest going to ... |