![]()

1 Introduction

‘The most significant changes since World War II’

The European economic crisis started in 2008 and has received much attention from scholars, journalists and policy analysts. Yet, critical political economic perspectives remain a minority in the large amount of commentary on the subject. Also, little has been written about the role of the media in interpreting the crisis and presenting governments’ responses to it. This is what this book seeks to accomplish, focusing on Ireland to make points often applicable to other European countries. Throughout the book, comparisons will be made with the experience of other ‘GIPSI’ countries (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Italy), Iceland, Scandinavia, the United States, Ecuador, Argentina and Latvia, among others, to contextualize the Irish case. In the conclusion, Irish media will be compared with European and American media in relation to their coverage of the crisis. It will be seen that Irish news organizations tend to be more conservative than European ones, and are, in this respect, more similar to the US media.

The argument can be stated succinctly. As explained in detail in the following pages, the policy response to the European crisis has reflected the interests of political and economic elites. The principle is readily demonstrated by the fact that when banks faced acute difficulties in 2008, European governments immediately mobilized national resources to support them. Conversely, since then, the majority of the population have not been bailed out, but have lived under austerity programmes that have attacked work conditions and public services. Media coverage of the crisis has mostly presented the views of political and economic elites because news organizations are themselves part and parcel of the corporate sector (or government sector if they are state-owned). This was stated candidly at the outset of the crisis by the Sunday Business Post, which declared that the ‘primary interest for the government to take into account is that of Ireland Inc’.1 Thus, the media do not present a broad range of opinions, but rather a relatively narrow spectrum of ideas. They present elites’ economic prescriptions favourably to the public and thus contribute to shape dominant political and economic ideologies. This does not mean that the population is always entirely convinced of the adequacy and fairness of the economic system and governmental policy, but it is safe to say that the media play a role in reducing popular opposition to them. Nor does it mean that critical viewpoints do not appear in the pages of newspapers. Of course, there is a diversity of opinions that appear in the media, including a number of individuals who have strongly challenged government policy, as will be seen in subsequent chapters. However, the point is that they are not representative of the general trends in media coverage.

The next chapter situates the European response to the crisis within the neoliberal economic model that has come to characterize advanced economies over the last four decades. The period has seen the financialization of the economy reach much higher levels than during the two or three decades following World War II, while credit- and debt-led growth has become more prominent. Moreover, there have been repeated assaults on the welfare state which have led to rising levels of inequality as elites have sought to reassert and maintain their position of power in society. The ongoing austerity implemented in Europe is a clear example of such dynamics.

That the crisis is used as an opportunity to dismantle the welfare state is no mere academic interpretation. It has been announced explicitly by European authorities. For example, Mario Draghi, the European Central Bank (ECB) president, declared in an interview with the Wall Street Journal that the European ‘traditional social contract is obsolete’ and that ‘there is no escape from tough austerity measures’. He further said that continuing ‘shocks’ would ‘force countries into structural changes in labor markets’. Accordingly, Europe’s population faces repeated challenges from corporate and political elites, a fact noted by the New York Times recently when it observed that ‘Americanized labor policy is spreading in Europe’. It remarked that in 2008, 1.9 million Portuguese private sector workers were covered by collective bargaining agreements, but that the number is now down to 300,000. Greece has cut its minimum wage by almost a quarter, Ireland and Spain have frozen it, and in general labour protections have been reduced in peripheral Europe, so that austerity is ‘radically changing the nature of Europe’s society’. The developments will transform the social fabric so deeply that the chief economist of the International Labour Organization described them as ‘the most significant changes since World War II’.2

The book proceeds chronologically and discusses the housing bubble, the rescue of the banks in 2008–9, the role of European institutions and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in bailing out countries in difficulty, and austerity. In Ireland, these topics have received attention from a number of authors, but their accounts have often focused on the personalities of bankers, builders and developers, and the political intrigues surrounding the economic crash, instead of interpreting the events within a critical political economic framework.3 Alternative policies that could be, or could have been, useful in dealing with the crisis are also addressed, such as debt default, economic stimulus and the possibility of leaving the eurozone. In each case, it is shown how the media have largely sided with government policy and corporate interests while opposing fairer strategies. In general, it will be seen that under neoliberalism, profits are privatized and losses are socialized. The bailout of private banks at taxpayers’ expense perhaps best illustrates this assertion. Moreover, there has been a democratic deficit in responding to the crisis, as the population has effectively not been consulted on which strategies should be implemented.

The book focuses on the print press, and in particular on the Irish Times, Sunday Times, Irish Independent, Sunday Independent and Sunday Business Post. They are appropriate for this study because in addition to being the most popular newspapers in Ireland, they are agenda setters. They shape to a great extent what other news outlets cover in print and on radio and television, and thus play an important role in determining the nature of public debate. The Irish Times is often referred to as ‘Ireland’s newspaper of record’ and has a readership of 390,000, while the Irish Independent has 650,000 readers. The Sunday Independent is the most popular of the Sunday newspapers, with a readership of about 940,000. The Sunday Times has a readership of over 400,000 and the Sunday Business Post reaches nearly 150,000 people.4 The methodology varies by chapter, depending on what is most appropriate and feasible to analyze media coverage of specific issues. Sometimes, a systematic quantitative analysis is used, for example to examine what proportion of news articles favour austerity versus those that oppose it. Elsewhere, media reporting is organized into themes that are prominent in the coverage of specific issues. Throughout, Ireland is compared to relevant cases, both contemporary and from recent history. This highlights the range of possible policy alternatives in responding to economic problems.

Ireland has often been presented as a poster child for austerity. In fact, the results have not been impressive, as will be discussed in more detail in later chapters. Economic growth is still weak or negative after a significant fall in 2008–9, GDP is still 8 per cent below its pre-crisis level, unemployment is still very high and debt has accumulated since the beginning of the crisis.

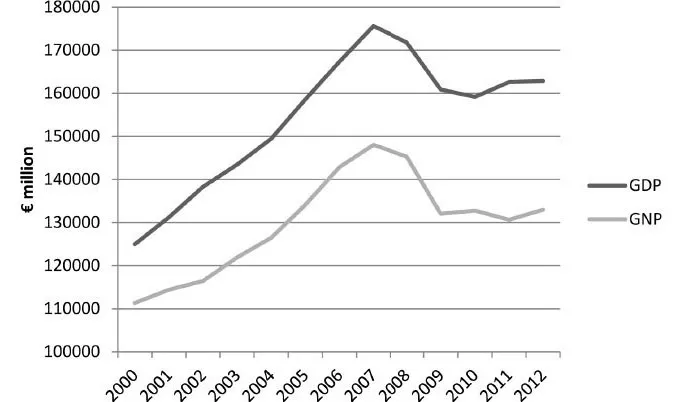

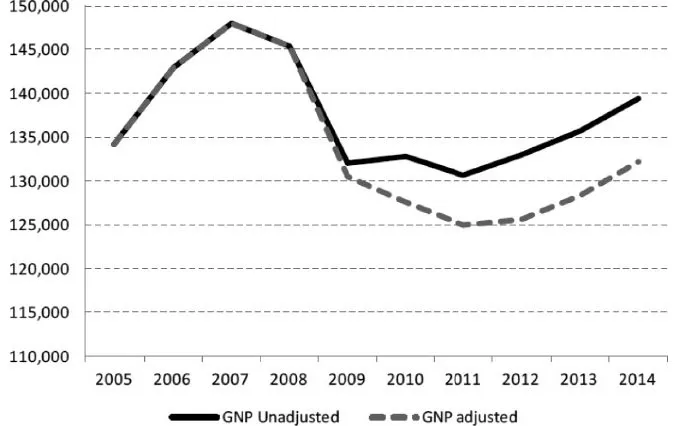

After increasing strongly during the ‘Celtic Tiger’ boom preceding the crisis, gross domestic product (GDP) and gross national product (GNP) dropped massively between 2008 and 2010, and economic growth has been relatively flat since then, which is not a satisfactory performance (see Figure 1.1). Irish data must be treated with caution, given the large impact of multinationals’ activities in the country. Transfer pricing, profit repatriation, royalty payments and accounting peculiarities greatly affect the published data, which may thus diverge significantly from economic reality. In particular, in most countries, there is little difference between GNP and GDP, but in Ireland, GNP is lower than GDP. The difference is mainly due to the profits repatriated abroad by foreign-owned multinationals operating in Ireland. Therefore, many researchers consider the lower GNP figure a better indicator of the state of the economy. In addition, GNP figures for the last several years have been artificially inflated because of the effect of ‘redomiciled companies’. These are companies that have relocated their headquarters to Ireland but do not generate any real economic activity in terms of employment or purchases of domestic inputs. Their numbers have grown very rapidly since 2008. Although they bring no benefit to the Irish economy, due to accounting rules, they raise Irish GNP, giving a rosier picture of economic activity than the reality. This means that the collapse of the economy has been deeper than the official data imply (Figure 1.2). Nevertheless, this book uses official data, bearing in mind the above caveats.5

Figure 1.1 Ireland’s GDP and GNP (constant market prices) Source: Central Statistics Office database, www.cso.ie

Figure 1.2 GNP adjusted for the effect of redomiciled companies (€ million, constant prices)

Source: ESRI, Quarterly Economic Commentary, Autumn 2013, www.esri.ie

During the boom years, unemployment was relatively stable, at about 5 per cent. It started rising rapidly in 2008, from 4.9 per cent (January 2008), to 9.5 per cent (January 2009), to 13.1 per cent (January 2010), and peaked at around 15 per cent in early 2012. Since then, it has decreased slightly, settling at a little more than 12 per cent in late 2013. However, as some analysts have noted, if broader measures of unemployment are used and the large numbers who have emigrated during the crisis are considered, the unemployment rate could have reached nearly 30 per cent. Also, beyond the numbers employed and job creation statistics, the quality of work and remuneration are important. For example, a recent government statistical release heralded the 58,000 growth in employment – or 3.2 per cent – in the year to the third quarter of 2013. While this is positive, a not insignificant portion of the added jobs were in the hospitality sector, the lowest paid and lowest value-added sector of the market economy.6

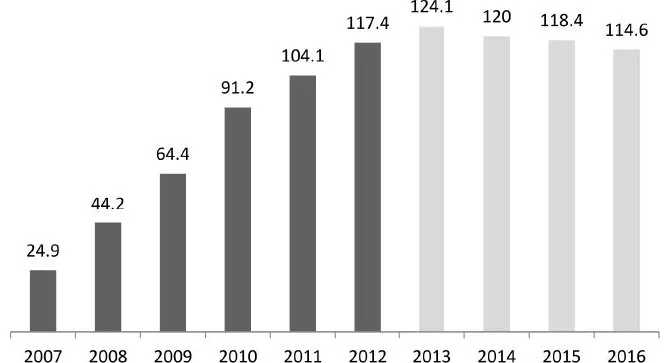

Government debt has surged in relation to the size of the economy ever since austerity started to be implemented (Figure 1.3). Early in the crisis, claims were heard that when government debt reaches the threshold of 90 per cent of GDP, the economy is in danger. As debt accumulated, this limit was breached and the new announced danger zone threshold became 100 per cent. It was then pushed up to 120 per cent after it was breached again. Austerity has not succeeded in reducing the state’s debt burden, and in fact has increased it. For example, general government debt as a percentage of GDP grew from 25 per cent in 2007 to 64 per cent in 2009 to 104 per cent in 2011 and is projected to reach 124 per cent for 2013. The situation may be even worse than those numbers indicate. If GNP is used instead of GDP, the debt ratio has increased from 29 per cent of GNP in 2007 to 78 per cent in 2009 to 130 per cent in 2011 and is projected to reach 153 per cent for 2013. Government projections, which have turned out to be over-optimistic in the past, do not even forecast a significant reduction in the debt ratio. They estimate a slow, gradual decrease in debt-to-GDP to 115 per cent by 2016, and to 150 per cent relative to GNP.7

Figure 1.3 General government debt as a percentage of GDP (%) (2013–16 are estimates)

Source: National Treasury Management Agency, www.ntma.ie

The next chapter describes the neoliberal political economy which has characterized developed countries since the 1970s and this book’s interpretation of news organizations. This sets the stage for the discussion of media coverage of the economic crisis in the remainder of the book.

Notes

1 R. Curran, ‘Riding to the Banks’ Rescue’, SBP, 30 November 2008.

2 B. Blackstone, M. Karnitschnig and R. Thomson, ‘Europe’s Banker Talks Tough’, WSJ, 24 February 2012, online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052970203960804577241221244896782 (accessed 11 December 2013); E. Porter, ‘Americanized Labor Poli...