![]()

1 Introduction

Regional Learning in Multinational Enterprises

The key actors in a global knowledge-based economy are multinational enterprises (MNEs). MNEs are essential protagonists in international innovation processes and increasingly organise their research and development (R&D) on an international scale. They provide important channels for the transfer of technological knowledge across national as well as cultural and institutional borders. MNEs can thus be analysed as cross-border networks for the innerorganisational transfer of technological competencies. As apparently footloose companies, they represent important nodes in a global economy. At the same time, however, in many cases at least the core activities of knowledge generation are still concentrated in the home countries of MNEs (Howells 1990; Filippaios et al. 2009). The home country also plays a vital role in the technological profile of most MNEs (von Zedtwitz and Gassmann 2002). It is therefore necessary to distinguish between the role of “MNEs as vehicles for technology transfer and MNEs as generators of new technology” (Dunning and Lundan 2009: 14). In both roles, however, in the cases of home-base-exploiting and home-base-augmenting strategies (Kuemmerle 1997, 1999) the regional environments of corporate headquarters and subsidiaries are an important source of contacts with suppliers, customers and competitors, for knowledge, R&D partners, political support and qualified employees (Cantwell and Mudambi 2005). Therefore, MNEs are not only internationally (or in some cases even globally) active organisations but also nationally and regionally embedded ones.

The tension and potential contradictions between the international reach of MNEs and their national and regional embeddedness have already been discussed in regional studies (Amin and Thrift 1992) and in international business studies which conceive transnational corporations as organisations capable of exploiting globalisation and localisation advantages simultaneously (Bartlett and Ghoshal 1986, 1989). However, this question has hardly ever been analysed on the basis of specific innovation projects (cf., however, Amin and Cohendet 2004; Kristensen and Zeitlin 2005; Forsgren et al. 2005; Rugman and Verbeke 2008). Our question, therefore, is how MNEs combine the advantages of internationally distributed innovation processes, institutionally embedded competencies and R&D facilities in specific innovation projects. How can the observed internationalisation of R&D and innovation projects be reconciled with the crucial role of domestic locations and competencies? To what extent do MNEs rely on dispersed and concentrated forms of knowledge production and application? How are corporate innovation processes conceived, coordinated and organised? What are the organisational and institutional conditions that shape, facilitate or impede cross-border innovation projects within the same company and with external partners?

The basic assumption of this study is that MNEs are neither completely footloose nor completely embedded companies. Instead, they decide strategically on what types of organisational, corporate, national and regional resources and collaborations they rely and what types of embeddedness1 are required for obtaining the desired outcomes. The strength of MNEs is thus the ability to shift between different forms of embeddedness and disembeddedness at the level of the single subsidiary (organisational level), the whole company (corporate level) and its external relations (for example, with regional companies and institutions). In this sense, regional embeddedness is a strategic option for MNEs, but not a necessity. MNEs can opt for both “footloose” global strategies and “embedded” ones in order to avoid the liability of being an outsider (Aharoni and Brock 2010) through a strategic involvement in the policies, business associations, networks and institutions of their host countries and regions. On the other hand, MNEs and subsidiaries can also choose not to get involved in their home country or in their host countries. Good reasons exist for not cooperating with internal or external partners, for not being involved in interorganisational networks or social relations and for not relying on regional and institutional patterns (for example, in order to avoid knowledge spillovers, which are generally only described as a regional advantage but may also imply the loss of proprietary knowledge; cf. Chapter 2). The strong rationality assumptions that underlie our understanding of the strategic and selective embeddedness of MNEs reflect the possibility that large multinationals may also adopt rational organisational strategies with regard to their task-specific and institutional environments (Kostova et al. 2008: 1001). However, faced with the dilemmas of innovation, which will be discussed in the next chapter, the outcomes may be much less rational than might be initially expected, as we will show empirically.

In this study we focus on the regional context of MNEs and their subsidiaries, following the insights gained from both regional and international business studies which indicate that “capability-acquiring R&D is often directed at regional or local clusters of innovation, which in the science-based industries are often linked to public or private research centers, and where agglomeration by other firms from the same sector generates localized knowledge spillovers in the area” (Dunning and Lundan 2009: 25). This specific focus does not imply that the national context is not also important for the technological profile and the knowledge generation of MNEs.2 However, national and regional systems of innovation can differ significantly (Crouch et al. 2009); firstly, in countries with a strong regional tradition (as in Germany) or an increasing decentralisation of competencies (as in France), the regional governance structures might be relatively independent of national patterns; secondly, each region is characterised by a specific sectoral mix and sometimes also by industrial clusters and by supporting institutions, i.e. by a regional innovation system (Asheim and Isaksen 2002; Cooke et al. 2004). This affects the scientific and educational subsystem, given that schools, R&D facilities and training facilities, industrial and innovation policies and intermediary organisations (chambers, business associations, unions …) also reflect the regional patterns of industrial specialisation. These regional varieties of educational, industrial and innovation policies are the result of administrative decentralisation processes as well as the result of different sectoral profiles. The regional business environment of each company (e.g. the proximate suppliers, customers and competitors) and often also the regional institutions, thus implicitly also the opportunities for localised learning in interorganisational networks, will therefore differ in general, even within the same country. We therefore decided to focus on the regional dimension in order to analyse the social and institutional embeddedness of corporate innovation processes.

We chose German and French MNEs because these countries belong to coordinated market economies (Hall and Gingerich 2009), which will presumably be characterised by stronger regional embeddedness. However, the patterns of organisation and innovation as well as the role of the regions in the political and administrative system of these countries differ significantly, which may give rise to different patterns of corporate innovation processes and regional embeddedness. Firstly, French organisational patterns have been characterised as centralised, bureaucratic, formalised and conflict-laden, while German patterns of industrial work have been described as consensual, task-oriented, decentralised and dominated by vocationally trained workers with a high technical expertise and a lower functional separation of production, monitoring and technical tasks (cf. Chapter 7 and Maurice et al. 1980). Secondly, the innovation patterns of these countries have been contrasted as mission- and diffusion-oriented (Ergas 1987b; cf., however, Mustar and Larédo 2002). The mission-oriented French innovation pattern is in general explained by the pervasive role of the strong, centralising Colbertist state, which organises and finances fundamental research independently from the universities and focuses on huge projects organised in close cooperation with mission-oriented public research institutes and large technology companies often owned or dominated by the state and its elites. Thirdly, the role of the regions also differs widely due to the stronger role of subnational regions in the federal German political system. Even if competencies and resources are likewise being increasingly shifted to the regional and also to the European level in France, the role of the regions will be still less important in the formerly highly centralised political and administrative system. Thus, it could have been expected that German companies would rely more strongly on “regional collective competition goods” produced by regional associations and decentralised political actors (employers, employees, economic associations, communes, federal states) within the framework of regional economies, while regional collective competition goods in France would be above all provided by central state agencies. In Chapters 5 and 6, however, we will see that this expectation has been fundamentally disappointed.

In order to place the regional embeddedness of corporate innovation process in the context of current debates, in the following we will analyse how the economic and societal context of MNEs is conceptualised in the field of international business studies and which contextual dimensions are especially important for the innovativeness of MNEs. In the next step, we will discuss current approaches in the field of regional studies in order to determine which regional dimensions are important for locally embedded companies. On this basis, we will specify our own research interest. Selected insights from the two—until now largely unrelated—fields of international business and regional studies will allow us to analyse the strategic and selective embeddedness of MNEs in their regional environments.

1.1 Embeddedne of MNEs in International Business and Regional Studies

The regional embeddedness of MNEs can be discussed from either the entrepreneurial or the regional point of view. We will start with the debates in the field of international business, which refers to the first perspective, and continue with selected approaches from regional studies.

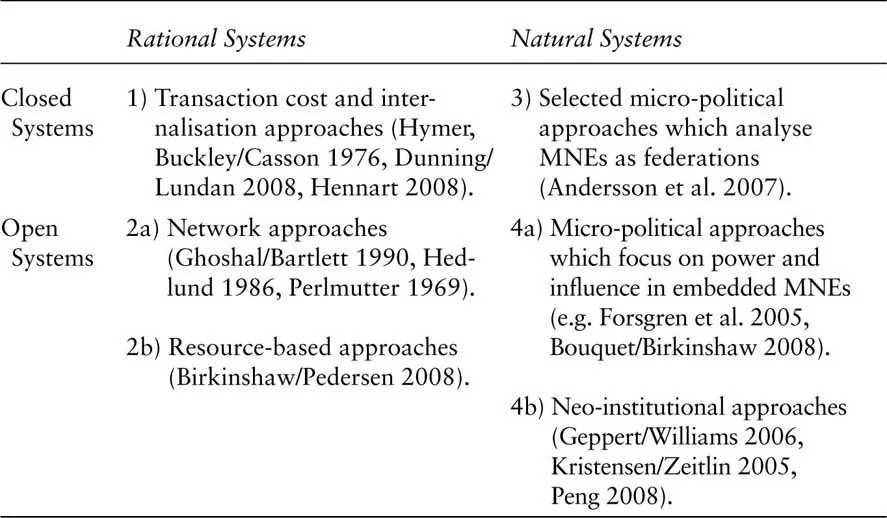

In the field of international business studies, the societal context of MNEs is discussed in four broadly different ways: firstly, as resources and factor advantages exploited by international companies; secondly, as a source of heterogeneity to which different multinational networks have to adapt; thirdly, as strategic resources which can be used in micro-political negotiations between headquarters, subsidiaries and proximate external companies; fourthly, as institutionalised environments that shape organisational policies and beliefs while being simultaneously shaped by the policies and beliefs of MNEs. These four perspectives correspond cum grano salis to well-known organisational theories (W. R. Scott 2001, 2003), especially to the theory of rational, bureaucratic organisations, to contingency theories, to micro-political and resource dependency approaches and to neo-institutional theories (cf. Table 1.1).3

Table 1.1 The Social Context of MNEs: Conceptual Approaches in the Fields of International Business Studies

The first perspective is related to the earliest approaches in international business (IB), namely the transaction cost and internalisation approaches that have been developed since the PhD thesis of Stephen Hymer in 1960, in general assumed to be the starting point of IB research. Hymer assumes that an MNE “must possess an internally transferable ‘advantage’, the control of which gives it a quasi-monopolistic opportunity to out-compete local firms” (Buckley 2002: 366). The MNE thus is analysed as a transaction cost-reducing device. In this perspective, the societal context is basically characterised by imperfect markets: “A firm will grow by internalizing imperfect external markets until it is bounded by markets in which the transactions benefits of further internalization are outweighed by the costs” (Buckley 2002: 368). In addition to internalisation (I) advantages of organisations (in comparison to transactions coordinated by markets), the so-called eclectic or OLI paradigm distinguishes ownership- and location- specific advantages (O and L) which refer to the competitive advantages of multinational firms (in comparison to its competitors) and of foreign locations in comparison to a domestic location (Dunning and Lundan 2008: XXIV). Locational advantages of a specific country are, for example, natural resources, low productions costs, access to (otherwise protected) markets, qualified or cheap labour or advanced technological and scientific know-how—advantages which can be the basis for different asset-, resource-, market- or efficiency-seeking strategies of MNEs. The internalisation or transaction-cost-based perspective can thus also take into account the exploitation of foreign technological capabilities, but not the interactive processes of its creation (cf., however, Hennart 2008: 140). In the transaction-cost framework, MNEs are therefore conceived as integrated organisations which can exploit existing resources or production factors, but do not contribute to the creation of dynamic capabilities in interorganisational or regional networks. It is assumed that “ownership advantages originate in the MNE’s home country” (Birkinshaw and Pedersen 2008: 373); a foreign locality is thus basically analysed as a bundle of static assets which can be exploited by appropriate location strategies. In the field of innovations, this corresponds to market-seeking or home-base-exploiting strategies in contrast to technology-seeking or home-base-augmenting strategies (Kuemmerle 1999; Le Bas and Sierra 2002; Cantwell and Mudambi 2005).

The second paradigm in international business, the network paradigm, focuses on the challenge of managing a complex, cross-border organisation which has to face heterogeneous national contexts. In contrast to the previous holistic approach to MNEs, which assumes that an MNE is a compact, rationally conceived organisation with a uniform goal, the network perspective proposed by Bartlett and Ghoshal (1986, 1989) and other authors analyses the MNE as a differentiated, sometimes multidomestic network characterised by relatively autonomous subsidiaries with increasingly specialised roles as well as different resources and capabilities. Subsidiaries with high competencies in technology, production, marketing or any other areas are designated as contributors or strategic leaders, in contrast to implementers or black holes, which are characterised by low competencies (Bartlett and Ghoshal 1986: 90). Corporate networks can be coordinated either hierarchically or heterarchically (Hedlund 1986). While hierarchical networks are characterised by dependent, hierarchically controlled subsidiaries—a coordination pattern which facilitates the exploitation of globalisation advantages due to company-wide rules, standards and procedures—heterarchical relationships between headquarters and subsidiaries allow the exploitation of localisation advantages due to the largely autonomous strategies of the various subsidiaries which can adapt to the particularities of a specific locality. Bartlett and Ghoshal (1986: 91), for example, observed a subsidiary classified as “contributor” which had “a technological capability and an R&D resource base that was much larger than subsidiaries in other markets of similar size or importance.” These types of companies should be used “as sources of information and expertise… . The best way to exploit this resource is not through centralized direction and control but through a cooperative effort and co-option of dispersed capabilities.” Such an exploitation of localisation advantages, however, is limited by the interest of exploiting globalisation advantages, pointing to the existence of a dilemma between national responsiveness and global competitiveness and often also between the geographical and the functional organisation of an MNE (Westney and Zaheer 2008: 347).

Depending on the role of localisation (L) or globalisation advantages (G), Bartlett and Ghoshal (1989) distinguish on this basis between international (L–; G–), multinational (L–; G+), global (L–; G+) and transnational companies (L+; G+). The transnational company is conceived as a network of interdependent subsidiaries which is able to simultaneously deal with the challenges of innovation, competiveness and local differentiation. The corresponding management styles have been described as ethnocentric, polycentric, geocentric and later also as regiocentric (Perlmutter 1969). In the first case, the locus of decision making is the home country; in the second case the host country; in the third case the world; in the fourth case supranational regions, for example, Europe.

The choice of these management strategies and styles is explained by the external, mostly sectoral and technological challenges that MNEs have to face in a specific task environment. These environments are characterised by sectoral, technological or economic factors such as competition, complexity, uncertainty and dynamics. The relationship between the MNE and their task-specific environment is thus conceived in a way typical for the contingency approach, which assumes that there is no one single best way of organising a company. However, not all organisational structures are equally effective; the best structure depends on the characteristics of the internal and external situation of an organisation (especially the stability of its markets, technologies, knowledge base and size).4

Thirdly, resource-based (cell 3 of Table 1.1) and micro-political approaches (cell 4a)5 have focused on power and exchange relations between headquarters, subsidiaries and their external, task-specific environment (especially suppliers, competitors and customers): “[S]ubsidiaries that are integrated in the MNE network and actively seek influence on the allocation of resources in the MNE” (Birkinshaw and Pedersen 2008: 371). Forsgren et al. (2005) emphasise that customer and supplier relationships are especially important for the development of new competencies which can be used by subsidiaries in order to strengthen their position in corporate networks. In a similar micro-political perspective, Andersson et al. (2007: 815) analyse MNCs as federations and arenas for bargaining. They show that the embedding of a subsidiary into external business networks, the knowledge of the headquarters regarding the subsidiaries’ business networks and above all the importance of the subsidiary for the company-wide product and process innovations are important assets in the power and exchange relationships between headquarters and subsidiaries. Westney and Zaheer (2008: 360) assume that the increased attention of the strategies of subsidiaries and their external resources reflect the increasing role of external companies for the organisational value chain. In a comprehensive overview of these micro-political or resource-based perspectives, Bouquet and Birkinshaw (2008: 479) distinguish between three different ways in which subsidiaries can increase their power and influence within the MNE: “They can achieve legitimacy in the eyes of MNC top executives, they can control resources that are unique and valuable to the firm, and they can become central to the various types of strategic networks in which MNCs are embedded.” A very important resource for R&D affiliates and other subsidiaries is the local knowledge base: the better “a subsidiary can contribute more creatively to technology generation within such a network, the better is the local infrastructure in the location in which it is sited, which increases its potential skill base and local linkages with other innovative firms and research institutions” (Cantwell and Mudambi 2005: 1124; cf. also Dunning and Lundan 2009: 25).

Recent micr...