![]()

1

Growing Up in the Shadow of Moral Exclusion

I guess you could say I live on the hyphen.

—Hadice, Syrian American, age seventeen

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the identity negotiation of immigrant Muslim youth living in the United States became decidedly more challenging. Although their nation was under attack, they were suddenly perceived as a potential threat to U.S. safety. The number of hate crimes against Muslims increased seventeenfold in a single year (FBI 2002). Overnight, “they,” Muslims, became the designated “others” who had to be watched, detained, and sometimes deported, in order to save “us.” Although many were already well integrated into the fabric of mainstream U.S. society, they came to be regarded as a potential security risk. While learning to navigate through this historical period has been daunting for everyone, young Muslims confronted particular psychological challenges. Hadice, a high school student in one of our studies, explained that Muslim American youth found themselves living then on a very precarious “hyphen” (Fine 1994).

The contentious nature of living on the hyphen did not dissipate after the initial attacks; to the contrary, the moral exclusion continues today (Opotow 1990, 2005), heightened with every local or global terror news story and intensifying the surveillance on Muslims (Bryan 2005; Cainkar 2004). While a full 80 percent of Americans thought racial profiling was wrong before 9/11, nearly 60 percent now favor racial profiling “at least as long as it was directed at Arabs and Muslims” (Maira 2004, 219). Even more alarming for Muslims is the finding that after 9/11, 30 percent of their fellow Americans thought that Arab Americans should be interned (Gallup 2006; Swiney 2006). At this moment in this country, Muslim young people are both culturally grounded and nationally uprooted, transnational and homeless, and swirling psychologically in a contentious diaspora (Bhabha 2005; Levitt 2000). In the last half decade, they have learned that their standing in the United States is provisional, as Sarah Gualtieri would argue, “not-quite-white. . . . not-quite-free. . . . subject to ‘the hyphen that never ends’” (2004, 65; from Suad 1999, 268).

At the same time, the experiences of Muslims in the United States after September 11 are not simply about alienation and struggle but also about their engagement with mainstream U.S. culture. Contrary to what many have predicted, Muslims in this country have not “given up” their American identity for the sake of their Muslim identity, despite the many pressures from Muslim fundamentalists and some Western intellectuals, who claim that one cannot be a good American and a good Muslim at the same time. As our data show in greater detail in chapter 5, the Muslim American youth that we studied for this book maintain in no uncertain terms that they experience no “clash” between their American and Muslim heritage. Unlike their counterparts in western Europe, Muslims in the United States are, in fact, well integrated into the mainstream culture. Integration does not require the erasure of culture but, rather, an engagement with a pluralistic society. According to the Pew Research Center’s national polls on Muslims living in the Western world, although 81 percent of Muslims in Britain chose to identify themselves as “Muslim first,” only 47 percent of U.S. Muslims felt the same way, which is similar to the percentage of U.S. Christians who identified themselves as “Christian first” (Pew Research Center 2007).1 Furthermore, the majority of Muslims in the United States, especially women, have a more positive outlook on their lives than do women in Muslim countries and are very concerned about Islamic extremism. Based on polls like these, the Pew report concluded that “the views of Muslim Americans resemble those of the general public in the United States” and depart from Muslims in Europe and elsewhere (Pew Research Center 2007, 4).

Perhaps because of these differences in integration policies, Muslims in the United States have one of the highest rates of citizenship, whereas most Muslims in Europe are still struggling to gain full citizenship, even when they have been legal employees for more than four decades. After France banned head scarves, Joan Wallach Scott made the obvious comparison: “If America permits the coexistence of many cultures and grants the legitimacy (and political influence) of hyphenated identities (Italian-American, Irish-American, African-American, etc.), France insists on assimilation to a singular culture, the embrace of a shared language, history and political ideology” (2007, B11) (see map 3). Thus in this book, in addition to describing many painful consequences of moral exclusion, we also offer many stories of sustained social integration to illustrate the U.S. context for Muslim immigrants (see color map 28). We indeed have much to learn from the experiences of young Muslims in the United States, about how we can start a new dialogue across the hyphens regarding culture, religion, and gender.

This book lays out a theoretical and empirical analysis of how first- and second-generation immigrant Muslim adolescents and young adults living in the United States have carved out hyphenated selves in the contemporary diaspora with creativity, resilience, and hope. Here hyphenated selves refers to their many identities, including their standings as Muslims and Americans, that are at once joined and separated by history, politics, geography, biography, longings, and losses. We explore here how these boys and girls, young men and women, make meaning of who they are amid the global conflict. Based on the attacks of 9/11, the global “war on terror,” and the domestic passage of the Patriot Act, we consider what happens socially and psychologically when young people suddenly become “designated others” in their own nation.

Although we provide a broad perspective on Muslim American youth in this book, our specific focus is on those who are either first-generation immigrants who were born abroad or second-generation immigrants who were born in the United States to immigrant parents. Currently, they constitute more than two-thirds of Muslims in the United States. As chapter 2 explains, these Muslim youth are distinct from other immigrants in that most have grown up comfortably in working-, middle-, or upper-middle-class families. They also are different from the native-born, African American Muslims in the United States because they are immigrants, and moreover, many “appear” to be white (Deaux 2000). As their stories in this book reveal, most of these young people were born and raised in the United States by immigrant parents with a relatively stable sense of the United States as home.

The accelerated emergence of the “Muslim American” label as a new social identity during the past decade presents a unique example of identity as a socially constructed and historically bound phenomenon (Ashmore, Deaux, & McLaughlin-Volpe 2004; Cushman 1995; Gergen 1994). The popular media, government agencies, and, more important, Americans of Muslim origin have increasingly adopted the label “Muslim American” to refer to Americans of specific religious or Middle Eastern geographical origins (Grewal 2003). Since the 9/11 attacks, a growing number of Americans have joined both national and local organizations under the label of “Muslim American” (Leonard 2003). For example, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, a small organization with eight chapters in 2001, is now the largest Muslim organization in the country, with more than thirty-two chapters. Most college campuses have Muslim student organizations instead of ethnic (e.g., Arab Student clubs) or home country–based organizations (e.g., Pakistani Student Organization).

Immigrants from Muslim countries who previously were identified by their ethnicity and home culture have now come to be identified by their religion. Jamar, a nineteen-year-old man in our focus group, summarized this historical transition:

Since 9/11, even more recent stuff . . . wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lebanon strengthened the bond of a lot of Muslims and I think that’s brought us more to the idea of being unified. It’s not worth us being individuals right now because we need each other and we all get support from each other.

Another young man in our focus-group discussions observed how current social contexts shape the overarching “Muslim” identity:

We really have to dislodge ourselves from the cultures that we came from and we should really become more Muslim as opposed to becoming, “I’m a Muslim Pakistani American” or “I’m a Muslim Syrian American.” There are more intermarriages between different cultures. A lot of African American brothers, Muslims, marrying Arab women, Pakistani men marrying Arab women or Arab men marrying Pakistani women. That’s one of the things happening nowadays and it’s a positive thing.

Thus despite wide variations in race, ethnicity, social class, and country of origin, a fragile collective identity of “Muslim American” has emerged in a relatively short period of time. We set out to study this social and historical construction and the effects of this “marking off” on youth.

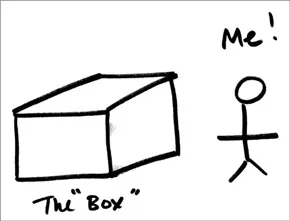

In this book we challenge ourselves and our readers to stay with the label “Muslim American,” which we use only reluctantly. We constantly remind ourselves and our readers that we are not talking about a single, unitary, fixed identity; rather, we are proposing a fluid, and therefore a figuratively hyphenated, identity that is open to variation at both the group (e.g., racial, ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity) and the individual levels. One of our participants, a young Pakistani woman, illustrated the problem with fixed, or “boxed” notions of identity in her map (map 1). She is delighted to be out of the box.

Beyond their shared background and experience of exclusion and surveillance, however, Muslims in the United States are extremely diverse. As we demonstrate in the next chapter, they come from more than one hundred different countries, belong to array of religious sects, and while some practice Islam, a majority consider themselves “just Muslims,” using the label as a cultural, not a religious, category (Genesis Research Associates, 2006). The young Muslims discussed in this book attend public schools and religious schools (sometimes Islamic, sometimes not), wear religious garb and baseball caps, enjoy the riches of the upper middle class and know the life of the working poor, drink beer with their parents and stay away from proms. In many ways they are unique individuals like any other young group of young people living in this country. Despite their enormous variation, however, they are brought together by the fact they all come from Muslim immigrant households and they all are experiencing something very unusual in post-9/11 United States. As map 1 reveals, these young people do not want to be stereotyped in a box.

Map 1. Noor, Female, Pakistani, Age 25

Our study of “Muslim American” identity, therefore, is not necessarily a study of ethnicity or religiosity but a study of an emerging collective identity influenced by not only ethnic and religious background but also the unique social and historic aftermath of September 11, 2001, in the United States. Accordingly, this book is a study of the psychological dynamics of working the hyphen by which young men and women negotiate their Muslim and American identities. Whereas we examine the role of religiosity and ethnicity as important background characteristics (Markstrom 1999), we concentrate on how a group of young people negotiates their Muslim and American identifications across contexts at a time when their group is under siege.

September 11: The Dawning of Moral Exclusion for Muslim Americans

In early September 2001, Muslims in the United States already were unusual immigrants. Relatively comfortable in the middle and upper middle classes of urban and suburban life, they spoke English, and many had enough social capital to feel as they belonged to U.S. society (see Deaux 2006; Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco 2001). They and their families were woven, albeit provisionally, into the fabric of American culture. As social theorists Sunil Bhatia and Anjail Ram (2001) argue, they implicitly rejected a notion of “national culture” and instead embraced identities that were “hybridized, diasporized and heterogeneous” (Bhatia & Ram 2001, 11). As the young artist Dorah wrote on her identity map, “America pre 9/11: integration while maintaining identity; building a community; human rights. . . . Much was still wrong with the world and America had its problems but there was still some semblance of sanity.” And yet within a few years, national opinion polls indicated that 46 percent of adults in the United States agreed that “It is OK to detain Muslims indefinitely to protect ‘us’” (Deane & Fears 2006). In the fall of 2001, these young people and their families were ejected from the national “we.” Quoting Dorah, a twenty-year-old woman (see map 2), “American Post-9/11: fear, hysteria, bias, ignorance . . . goodbye Geneva conventions, hello war crimes, Abu-Ghraib. . . . The U.S. Muslim community cowers in fear.” Their hyphenated identities were being perforated or, as one Muslim comedian put it, “We went to bed white on 9/10 and got up ‘Muslim’ on 9/11.”

For the young people of this book and their families, 9/11 indeed marked a rupture in their identity negotiation process. They underwent two kinds of cultural disruption. First they were placed under suspicion, socially and psychologically, within the nation they considered “home.” Suddenly cast “amongst those whose very presence is both ‘over-looked’—in the double sense of social surveillance and psychic disavowal—and, at the same time, over-determined—psychically projected, made stereotypical and symptomatic” (Bhabha 2005, 13). Varied forms of discrimination and surveillance now penetrated their communities, social relationships, and self-consciousness. As one participant, Aisha, noted:

I remember that day [9/11/01] my father drove home a number of children from school, a religious school. As he dropped them at the elementary school, where they would meet their parents, the police were there, taking names, phone numbers, and licenses. That was frightening enough, but as we drove off we found ourselves in a big traffic jam and some woman screamed out of her car, “Why don’t you just go home?” I knew then that everything was going to be different.

Map 2. Dorah, Female, Palestinian, Age 20

Second, their other community, the Islamic diaspora, was shaken as well. Their geographic imaginary, as Edward Said wrote (1979), was shattered. Despite their personal, often quite resilient, responses, these two geographic imaginaries of belonging had become destabilized. Saleed, age twenty-one, a U.S. citizen with family roots in Palestine, explained how throughout his life he had rejected the label of “American” and then found himself considered “American” on his first visit to Palestine.

I realized that when I would walk into a room, they would all get up to shake my hand, and tell each other in Arabic “this is the American” and I’m like, wait a minute, what’s going on here, and I realized that I don’t really fit in there, or here, and I guess to them, I’m American, over here I may choose not to be.

Sociologist Rabab Abdulhadi, a Palestinian in New York, tells a similar story about looking for “home” on 9/11, running down the street.

I am already bracing myself for the battle between “us” and “them.” My hand instinctively goes to my neck to hide the chain with the Qu’ranic inscription my students . . . gave me before I left Cairo. Luckily I had forgotten to put it on today. My split lives are on a collision course again: I feel like such a traitor for passing. But wouldn’t it be better to pass today? Do I want to identify with “them,” though? Do I want to escape the collective guilt by association, the fate of my fellow Arabs, Palestinians and Muslims? Should I renege on my roots. There is this nagging feeling that I need some sort of a symbol to shout to the world who I am. I want so much to defy this monolithic image. (2003, 92)

She concludes her essay with questions of home.

When 1,000 are detained and 5,000 are not so voluntarily interviewed, New York and indeed the United States, feels suspiciously like the occupied West Bank. But this is not the West Bank, where most Palestinians are subject to the same misery and terror and, as my mother would say, “Illi waqe ‘ala nass waqe’ aleina” [We are very alone here: our diasporic lives are fragmented]. Our souls are split open. It is perhaps time to go home, but back home exists no more. (2003, 100, italics added)

In this book we present a developmental story about this splitting: the story of immigrant Muslim youth living in the United States responding and resisting with Dorah’s (see the previous map) “glimmer of hope—yet and still.” We try to learn what happens when young people find their “souls split open” and “home exists no more.”

Designating the “Other”

What is currently happening to Muslim people in general, and to young Muslims of this generation in the United States, is not historically unique in this country. These rhythms of ethnic marking and exclusion resonate with the story of our nation. As children exiled from a place they called home, these Muslim American youth walk in the historic psychological footprints of Native Ame...