![]()

PART I

Reading Kipling in America

“I move,” said the legislator, “that we now take up the–” “Mr. Chairman,” interrupted a Senator, “hasn’t that white man’s burden poetry been worked about enough?”

—A joke printed in the North American,

a Philadelphia newspaper, March 13, 1899

In the joke above, Kipling’s poem has overstepped its bounds when it enters the Senate halls, but as I demonstrate in this section, the poem was indeed “worked about” in Congress and throughout the culture at large. On the reception of “The White Man’s Burden” in the United States, little has been written that goes beyond general assertions about its influence on U.S imperialism.1 This is an oversight of what was seen at the time as the era’s most important literary incursion into the realm of international politics. After its initial U.S. publication in the February 1899 issue of McClure’s Magazine, the poem was extensively reprinted through the McClure’s newspaper syndicate; according to one estimate, it appeared in at least six-hundred thousand copies of newspapers nationwide and reached over one million American readers.2 Its publication accompanied an unprecedented surge in Kipling’s popularity. In the following months, newspapers produced supplements devoted to minutiae of Kipling’s life and career; a monthly journal entirely devoted to miscellaneous facts and opinions about Kipling enjoyed a year-long run in New York; publishers took advantage of the fashion by hastily rehashing and printing as free-standing pamphlets brief articles on Kipling taken from monthlies; and all sort of writers and politicians found ways to comment on Kipling’s writing and on “The Kipling Boom.”3 One reviewer concluded, “Whatever be the reasons for the popular appreciation of ‘The White Man’s Burden,’ the immensity of that appreciation is most remarkable. Sermons have been preached about it, editorials written on it, jokes made of it, [and] parodies innumerable and cartoons have been inspired by it.”4 To satirize the fashion of banking on Kipling in the United States, the London Academy printed a false prospectus for “Kipling (Limited),” a U.S. corporation that would buy up and reproduce Kipling’s childhood “attempts at pothooks and penmanship,” as well as his current writings: “The Company will be vigilant that no imperial crisis shall pass without poetic comment from Mr. Kipling’s pen. It trusts also that it will be successful in inducing Mr. Kipling to give these political poems a form which shall be easily parodied: thus providing for increased publicity.”5

And, indeed, parodies abounded. Through references to “The White Man’s Burden,” something as vague as “U.S. imperialism”—as a set of policy choices, a philosophy, a popular mood, a logical rationale for certain actions—could be targeted and evaluated. Kipling’s strident trimeter, repetition, and ordered, rhyming stanzas made an easy target for anti-imperialists interested in striking a satirical blow to expansion. E. S. Martin in Harper’s Weekly wrote that the poem seemed to have a “red rag effect on the opponents of expansion,” being “chiefly quoted by persons who find fault with its sentiments.”6 One 1899 parody mimicked the poem’s emphatic meter while pointing out its self-serving rationale for wrongdoing:

Take up the sword and rifle

Still keep your conscience whole—

So soon is found an unction

To sooth a guilty soul”7

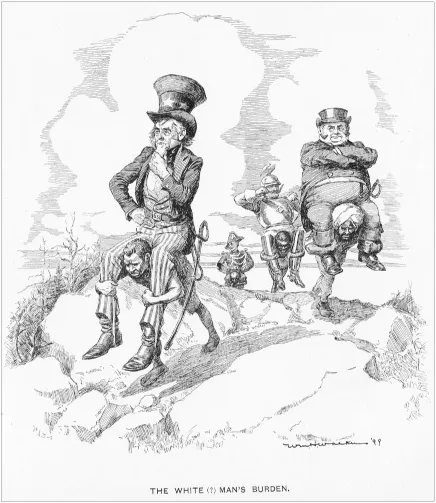

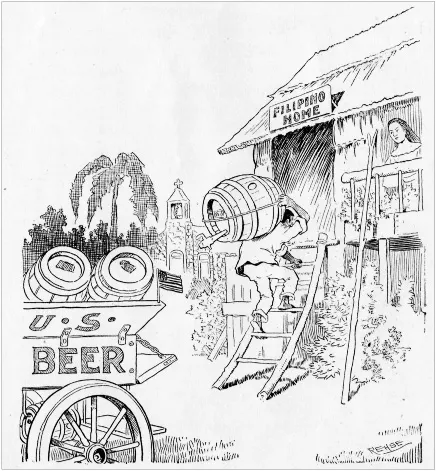

Other satirical treatments rendered the burden not as a trial but as stolen treasure; Robert Underwood Johnson’s 1901 parody of the poem answers the question “What is the White Man’s Burden?” in this final couplet: “Go bribe new ships to bring it—/The White Man’s Burden—loot!”8 Or, as another parodist quipped, the “burden” was not to spread civilization but to teach the Philippines “what interest and taxes are / And what a mortgage means.”9 A favorite anti-imperialist tactic was pointing out the poem’s obfuscating reversal, which diplomatic historian Albert K. Weinberg called in 1935 an example of onomantithesis, the figure wherein any unpleasant thing is designated not by its usual name but by the antithesis of its usual name. In Kipling’s poem, Weinberg writes, “imperialism, connoting the burden of the race of color by military subjugation if not economic exploitation, was called in ‘onomantithesis,’ the white man’s burden.”10 As one critic of the day complained, “The trouble with the kind of White Man’s Burden that Kipling talks about is that it really means the Brown Man’s Burden. It means the white man taking his own burden and putting it upon the brown man’s back and compelling the brown man to carry it.”11 Visual images pointing out this reversal frequently appeared in political cartoons depicting Uncle Sam carrying off bags of Filipino wealth or riding atop a Filipino over the title, “The White Man’s Burden” (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. “The White (?) Man’s Burden,” by William H. Walker, Life 33 (March, 16 1899), 201.

Figure 2. “Taking Up the First Installment of the White Man’s Burden,” by George Washington Rehse, American Monthly Review of Reviews 21, no. 4 (1900), 392.

In chapters 1 and 2, however, I aim to show that the poem was more than a jingoistic rallying cry or an easy mark for anti-imperialists. Readers of the poem expressed a surprising amount of confusion about its meaning, and at the root of this confusion, I argue, was their ambivalence about the idea of the United States taking up a “white” imperial mission. In chapter 1, I examine the poem’s reception to argue that, rather than supporting the linkage between whiteness and American empire, the poem exacerbated anxieties about the meaning and importance of whiteness for a U.S. global mission. In other words, while some satirists demonstrated the poem’s hypocrisy by pointing out the onomantithesis in Kipling’s binary treatment of black beneficiaries and white servants, for some readers Kipling’s binary was not deceptively reversed but troublingly collapsed in a context where the meaning and stability of whiteness was in question.

In chapter 2, I interpret Dixon’s best-selling novel The Leopard’s Spots: A Romance of the White Man’s Burden as a response to the anxiety about white American empire that Kipling’s poem provoked. Dixon’s novel attempted to resolve the poem’s contradictory meanings, especially for Southern Democrats who were invested in visions of racial homogeneity and domestic segregation and troubled by the poem’s destabilizing conception of whiteness. I contend that in attempting to envision a white man’s burden that would appeal to the South as well as the North, to Democrats as well as Republicans, Dixon sought to revise Kipling and extend the poem’s appeal beyond the party of Theodore Roosevelt, the Republican imperialist to whom the poem was initially addressed. To create this appeal, Dixon tried to create a more stable sense of the white American imperial subject, and in doing so he had to address the questions that I argue were continually provoked by Kipling’s poem: Who is the white man? What does the United States have to do with a white racial mission? And how does that mission coexist with internal racial heterogeneity? Ultimately, my purpose in chapter 2 goes beyond offering another example of Kipling’s influence in provoking these questions, and, instead, examines Dixon’s popular reinterpretation of Kipling as a sustained literary effort to reorganize U.S. racial categories and hierarchies in light of a global mission.

![]()

1

The Burden of Whiteness

In February 1899, a query was posed to “Chappy,” the persona of a news columnist who served as resident expert for readers of the Milwaukee Journal:

Dear Chappy,

Please state in your column what is the real meaning of the poem of Rudyard Kipling, entitled The White Man’s Burden, published in McClure’s Magazine for February, 1899.

Does it refer to expansion or to the ills of our present social system?

It may seem strange to you, but many people of intelligence are divided on this subject, and it has caused considerable discussion. Please give us your idea as to which meaning is intended by the poet.

Yours very truly, T. F. H.1

This particular question is one that literary critics today seldom puzzle over—when Kipling scholars write about this poem, they generally treat it as one of Kipling’s simpler works, important as a reference point for comparison with the author’s other works but not complex enough to merit its own analysis.2 In short, literary critics seem inclined to agree with the interpretation given by Chappy, who answers T. F. H.’s question with a quick gloss of some of Kipling’s lines and concludes with some chiding condescension: “It is clearly an ‘expansion poem,’” which “seems to me to be quite clearly the meaning of the highly polished verses and I quite fail to understand how the other meaning in your letter could possibly be associated with them.”3

Kipling’s familiar and frequently cited poem is rarely the object of serious literary analysis, but the story of how “The White Man’s Burden” was received in the United States demonstrates that the poem’s meaning and effect are more complicated than often supposed. Historians have long held that Kipling’s poem offered to the United States a key formulation of expansion as selfless duty, a moral justification based on idealism and racial mission for empire in the newly acquired Philippine islands.4 More recently, scholars of U.S. imperialism have interpreted the poem, subtitled “The United States and the Philippines,” as a representative articulation of transatlantic imperial identification.5 But by taking seriously T. F. H.’s question about interpretation and looking for its echoes throughout U.S. political and literary discourse, we see much more. As I contend in this chapter, the reception of Kipling’s poem in the United States reveals the poem’s important role in channeling anxieties about the definition of whiteness and its relationship to U.S. empire and American “social ills.” Following this trail of interpretive uncertainty, we see the productive confusion that arises when a poem enters into the public sphere as a political document, a confusion that points us back to some of the classic concerns of interpretive method: Where is the “real meaning” of a poem? What does a poem do in the world? For wondering what Kipling’s poem in fact meant and did became one way that readers in the United States pondered some of their most pressing questions of national and racial identity.

As a reception study, this chapter suggests that the meaning of Kipling’s poem derives not only from authorial intention or formal features but also from the interpretations made by readers of the poem in particular socio-historical contexts.6 While I am primarily interested in using reader response as a window onto the turn-of-the-century U.S.’s vexed ideas about race and imperialism, “The White Man’s Burden” also provides an interesting case study in literary reception, one in which readers’ interpretations range widely, due in part to a conscious perception of the literary work as also a political document, a sort of mixed genre that readers experienced as unprecedented. During the three-year period of the Filipino American War following the poem’s release, commentators often spoke of Kipling as a writer whose importance transcended “merely literary” concerns. Frederick Laurence Knowles published a Kipling Primer, a guidebook intended to help the common American reader understand the poet’s importance; it introduces “The White Man’s Burden” as “more widely read, discussed and parodied than any other poem of the time” and affirms another critic’s claim that the poem is “an international document of the first order of importance.” Walter L. Sheldon chose Kipling as his topic for an essay in the series “Ethical Addresses,” stating the poet’s reputation to be not “a problem for the literary critic or the man of letters, belonging only to the sphere of literature” but, rather, an issue of much broader political relevance. Kipling’s reviewer in the Outlook similarly identified him as a writer who, although a private individual “detached from the world of affairs,” has “won the place of a leader” among English speakers. And Paul Elmer More in the Atlantic Monthly contended that no other English or American poet has ever enjoyed popularity on par with Kipling, partly because others such as Tennyson, Browning, and Longfellow “remained more or less isolated in the realm of pure art,” while Kipling used art to voice ideas that shaped world events.7 We may wish to question the idea that other poets were more isolated in the “realm of pure art,” but the perception that Kipling was special in escaping it evoked different reading practices.

Certainly Kipling intended the poem to influence U.S. foreign policy. Before its publication in McClure’s, he sent an advance copy to Theodore Roosevelt, the recently elected governor of New York and hero of the Spanish American War. Kipling perhaps hoped that Roosevelt would find the poem relevant to questions gripping the United States: What did it mean to have beaten Spain, liberated Cuba, and taken possession of several Caribbean and Pacific islands, the most populous and distant of which were the Philippines? And, more urgently, what should be done with these new possessions? Roosevelt passed the poem along to fellow expansionist Henry Cabot Lodge, noting that it was “rather poor poetry, but good sense from the expansionist viewpoint.” Lodge, the famously Anglophobic Massachusetts senator, appreciated sound but took issue with sense: “Thank you for the advance copy of Kipling’s poem. I like it. I think it is better poetry than you say, apart from the sense of the verses.”8 Despite their different evaluations of the political message, both politicians take the poem’s “sense” or meaning as something easily identified and separated from its form as poetry, an assumption challenged both by a close reading of the poem and by the story of the poem’s broader reception.

Read as a poem and as a policy statement, “The White Man’s Burden” resonated widely in a variety of cultural forms such as congressional debate and presidential policy, scientific writing, advertisements, sermons, newspaper and magazine editorials, personal letters, political satire, and literary criticism. Examining such a broad reception requires attention to divisions within the culture’s politics and within its reading publics. Reception studies have explored the ways that interpretation can be motivated or primed in a number of ways: by political agendas, individual subjectivities, cultural assumptions, and literary expectation regarding genre and convention.9 But when poetry is taken as policy, poetic ambiguity offers particular grounds for motivated interpretations by readers with varying interpretive skills. As a columnist with the Kansas Atchison Daily Globe wryly noted, “That is the trouble with poetry; people do not understand its meaning. We have read Kipling’s poem, at the expense of a headache, and we say he advises the Filipinos to take up the white man’s burden; that is, they should quit lying around in the shade like dogs, and go to work, die of dyspepsia, and go to hell, like the white man.”10 Here ideas about poetic indirectness create a satiric opportunity to rewrite the poem’s meaning, expressing a sarcastic version of T. F. H’s seemingly sincere sense that the poem might be critical of the nation’s “present social system.” And yet in doing so, the Kansas columnist only extends the poem’s authority in turn-of-the-century debates about U.S imperialism. Instead of disqualifying poetry from serious discussion of foreign policy, poetic ambiguity in the case of Kipling’s poem enabled a literary text to be marshaled in a number of debates. And one of the most important of these was about the importance of race for charting a global role for the United States.

With this ambiguity came a troubling anxiety about the meaning of whiteness. I argue that by celebrating whiteness as both an explanation and a goal of the civilizing mission, Kipling’s poem invited reflection on the meaning and definition of whiteness that its fragile and shifting construct could not completely bear. This is not to say that this is the essential or ultimate meaning of the poem but that an interrogation of whiteness and empire was its most significant and presently unacknowledged social effect. The concept of race as a key tool for explaining world politics, history, and human potential reached its height at the turn of the twentieth century and was about to begin its decline as a legitimate scientific concept. In the interpretive controversy over Kipling’s verse, we can see writers dwelling on and contending with the concept’s fractures and contradictions, intentionally or unintentionally making its incoherence more visible, for widely different purposes. In other words, while the poem both harnessed and reinforced certain historical constructions of race such as “Anglo-Saxon” or “white,” it also placed these groupings in a spotlight that cast critical attention on these strategic gro...