![]()

1 Arendt and the Trial of Adolf Eichmann

Contextualizing the Debate

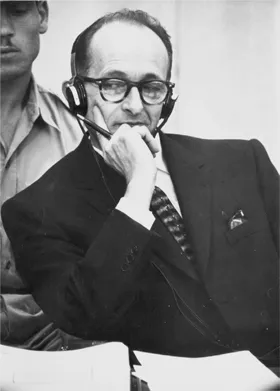

Evil in its total banality: this is what Hannah Arendt claimed to have seen in the figure of Adolf Eichmann when she observed him in an Israeli court in 1961. Eichmann was considered a core member of the Nazi leadership and would have undoubtedly been tried at Nuremberg in 1946 alongside Göring, Speer, and Hess among others for war crimes had he not fled Europe following the collapse of Germany’s Third Reich. He was living in relative obscurity in Argentina when he was captured by the Israeli Secret Service and clandestinely returned to Jerusalem to stand trial for his central role in the genocide of European Jewry.

Initially, at least, Eichmann was one of only a handful of officials in the Nazi SS whose sole job it was to implement or make operational the regime’s various political and physical solutions for what it identified as its Jewish problem. Among other things, this entailed organizing the forced emigration and so-called resettlement of Jewish communities throughout (eastern) Europe and later, as the war progressed, overseeing their transport first to the ghettos and then to the camps where, as it is known, large numbers were systematically killed. While Eichmann never denied his role in helping solve Germany’s Jewish problem—he claimed to have been an “expert” in Jewish affairs, a pro-Zionist no less, and an idealist—he stressed repeatedly that he harbored no ill-will towards the Jews and acted not from base motives but out of a sense of responsibility and duty and with an eye towards personal advancement. In his view, the annihilation of the Jews was “one of the greatest crimes in the history of humanity,” but a crime in which he did not participate directly. He had served the regime only as a midlevel bureaucrat on the margins of power, someone who sat at his desk and did his work, evacuating and deporting rather than killing. And although his account was not entirely accurate, Eichmann’s rendering of his Nazi past was, in Arendt’s view, nevertheless somewhere in the general vicinity of truth: “Technically and organizationally, Eichmann’s position was not very high; his post turned out to be such an important one only because the Jewish question, for purely ideological reasons, acquired a greater importance with every day and week and month of the war, until in the years of defeat—from 1943 on—it had grown to fantastic proportions.”

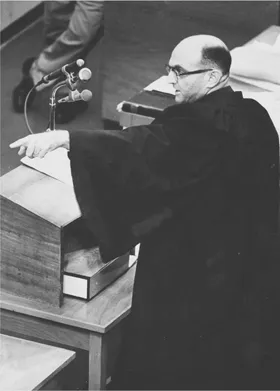

Not surprisingly, the prosecution in Jerusalem advanced a somewhat different view of Eichmann’s position in the Nazi hierarchy and role in the genocide of European Jewry. Indeed, Gideon Hausner, Israel’s attorney general at the time and lead prosecutor in the case against Eichmann, maintained that it was Eichmann and Eichmann alone whose business had been the destruction of the Jewish people in its entirety. He had been the architect of Nazi terror against the Jews and, in Hausner’s words, “the central pillar of the whole wicked system”—personally selecting the sites of the gas chambers, choosing the kind of poisoned gas that was to be used in these chambers, and specifying the number of people to be killed in them daily.1 And while Eichmann may have performed his “bloody craft” from the security of his desk in Berlin—in this Hausner echoed Arendt’s claim that Eichmann represented a new kind of criminal—in the end, the prosecution settled on constructing a somewhat more predictable, conventional, and politically more useful portrait of the former Nazi official. Sitting in a bulletproof glass enclosure—designed to protect the accused from possible attack while in court—Eichmann emerged from mounds of documents and weeks of oral testimony by survivors as a sadistic, demonic figure even while, it should be said, most of those who testified had no direct dealings with the man and were brought to the stand by the prosecution to humanize the larger historical picture of Nazi atrocity.2 In the view of the prosecution, he was a consummate liar and “savage sociopath whose abominations made the crimes of Genghis Khan, Attila, or Ivan the Terrible … pale in significance.”3 Where Arendt saw in Eichmann a disturbingly average man of middling intelligence who, while implicated in a crime of gigantic proportions, was in the end “simply” a petty, deferential, careerist bureaucrat, someone who was not incited by ideological convictions, driven by base motives, or, based on the evidence presented, psychologically capable of committing the kind of acts of overt violence attributed to him; where Arendt saw, in other words, not Attila the Hun or Ivan the Terrible but the embodiment of something she described as evil in its total banality, the prosecution produced and pursued a diabolically wicked, morally monstrous Nazi official whose hatred of the Jews was relentless in its pursuits, deadly in its expression, riddled with sadistic impulse, and far from banal.

Figure 1.1. Eichmann in Court, 1961. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Photo Archive, Jerusalem, Israel.

I.

Considerable outrage greeted Arendt’s report of the trial when it was first published in the New Yorker as a series of articles in 1963. And in the four decades since, her claims regarding the meaning of the Final Solution, her arguments regarding the nature of individual responsibility, agency, and culpability under conditions of terror, and her scathing review of Israel’s case against the accused continue to incite and confound commentators. Two issues in particular have consistently aroused the ire of some readers and the interest of others, and both go to the heart of the problem I want to take up in this and subsequent chapters. There is, first, Arendt’s insistence that great evil is not necessarily a reflection of evil motives or an expression of natural depravity. Such evil, she argued, is better understood as the outcome of a certain thoughtlessness or inability to think—that is, an inability to think from another’s point of view or, as Elaine Scarry has more plainly put it, “to follow the path of the bullet.”4 To regard Eichmann as a perverted sadist or to see in his actions a straightforward display of demonic intelligence was to fail, utterly, to grasp the criminal character of the accused and the nature of his crime. It was also, significantly, to misidentify the larger problem that he represented and that now confronted the world in the aftermath of Auschwitz. “One cannot extract any diabolical or demonic profundity from Eichmann,” Arendt wrote.

He merely, to put the matter colloquially, never realized what he was doing. It was sheer thoughtlessness—by no means identical with stupidity—that predisposed him to become one of the greatest criminals of that period…. [S]uch thoughtlessness can wreak more havoc than all the evil instincts taken together … —that was, in fact, the lesson one could learn in Jerusalem.5

Arendt would return repeatedly to parsing the implications of this lesson throughout the rest of her intellectual life in an effort to make sense of and clearly render the relationship between thoughtlessness and the capacity for evil. While most of the animating links of this relationship would remain an impressionistic patchwork of claims and questions, what she seemed to see clearly and refuse was the all too convenient tendency to equate great evil with a wicked heart. This refusal led many of her critics on the publication of her report to charge that she was, in effect, absolving Eichmann and others in the Nazi leadership of responsibility for their part in building and administering a machinery of death. Her insistence that one of the most remarkable and, for the purpose of comprehending great evil, relevant things about Eichmann and others like him was his—and their—extraordinary shallowness and normality was regarded as an affront to the memory of those murdered.6 It worked against the pull of suffering graphically portrayed in the liberation footage of the camps—shown in Jerusalem as at Nuremberg but, significantly, as evidence not “just” of war crimes but of the Holocaust.7 It worked against the pull of suffering graphically recounted in the testimony of survivors even while Arendt went on to argue that this “normality” was, by implication, infinitely more terrible and “terrifying than all the atrocities put together.”8

If Arendt was thought to have exonerated Eichmann by suggesting that he was “perfectly incapable of telling right from wrong” and “never realized what he was doing”—issues to which I return in subsequent chapters—she provoked an even greater firestorm in challenging the ostensibly self-evident distinction between the victims of Nazi atrocity and their persecutors. This distinction was, of course, sharply drawn by the prosecution in Jerusalem and easily assumable by all who had encountered the many postwar images of corpses and open graves. Arendt contended that things were not so clear cut: there was a chapter, by far “the darkest chapter of the whole dark story” as she described it, that had been omitted in Jerusalem but was nevertheless essential to understanding the totality of the moral collapse caused by the Nazis.9 And this chapter concerned the cooperation of the Jewish leadership across Europe in working out the details of SS directives, implementing the policies of Nazi officials, and shoring up the power of occupying forces. In fact, the cooperation of Jewish authorities constituted a cornerstone of the Nazi’s program, and, in Arendt’s view, this cooperation had a great deal to do with its success. As Arendt put it bluntly in what Lawrence Douglas describes as “the most controversial and vilified statement in her book”:10 “The whole truth was that if the Jewish people had really been unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between four and a half and six million people.”11 If Eichmann bore responsibility for the death of millions—and Arendt was absolutely clear that he did—a significant measure of responsibility for these deaths lay also with the Jewish authorities. Indeed, of the numerous outbursts by spectators in the Jerusalem court that disrupted the proceedings, a significant number “were directed not at Eichmann, but at those Jewish witnesses who had served prominently in the Judenräte.”12 And of all the hard questions Hausner put to the many witnesses he called to testify—why did you not rebel? resist? or try to escape?—he did not ask them what for Arendt was the more troubling question, that is, why had they cooperated in their own ruin? As Arendt saw it, Hausner’s lapse while grave was not surprising: the omission of this chapter from the prosecution’s otherwise meticulously spun story boldly underscored for her the extent to which the trial sought primarily to display a certain truth about Auschwitz rather than decipher its actual horror, in the interest of an emerging Israeli national identity rather than justice.

Figure 1.2. The prosecutor at the Eichmann trial, Gideon Hausner, 1991. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Photo Archive, Jerusalem, Israel.

It is now a matter of public record that Hausner and Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion had sought to use the trial to establish “the correct historical perspective” on what would come to be known, after and in large measure because of the trial, as the Holocaust.13 Their strategy—of fashioning a “canvas soaked in blood and tears … that would reach the hearts of men”—entailed explicitly interweaving two narratives, one having to do with the suffering and destruction of the Jews, not only in the context of the second world war, but across centuries, beginning with the Pharaoh in Egypt and climaxing in an unimaginable martyrdom. “It is not an individual in the dock at this historic trial,” wrote Ben-Gurion, “and not the Nazi regime alone, but anti-Semitism throughout history.”14 This narrative of persecution was coupled with another detailing the remarkable passivity of the world at large as a tragedy of gigantic proportions unfolded.15 And then there was, of course, a lesson to be drawn from the story for which this “correct historical perspective” was required—in fact, several different lessons for different audiences. As Ben-Gurion envisioned it, the trial was to foster a certain consciousness among Jews about their vulnerabilities in a historically hostile world, dramatically rehearsing what it meant to live among non-Jews and emphasizing the obvious conclusion to be drawn from the incontrovertible fact of such vulnerability, that only a Jewish state could guarantee the survival of the Jewish people. For a non-Jewish world, brought into the courtroom by television,16 the trial was to underscore the extent of the destruction of the Jewish people and the culpability and, thus, responsibility of Western powers for the slaughter of innocents: the free world had not only failed to act in either a swift or decisive fashion as a nation was led to slaughter, but had happily forgotten about the catastrophe once the war ended.17 They were to be reminded of their shameful inaction and obligations to the new Jewish state. Finally, for an Israeli audience, the trial was to do a different kind of work, repairing and consolidating an otherwise fractured set of histories through education and “factual enlightenment.” Among other things, this would entail rehabilitating the picture held by many of Diaspora Jews as meek, submissive, and hapless victims who went like sheep to the slaughter.18 What would emerge, therefore, during the trial through witness testimony and in place of this hapless victim was the survivor: Israel (primarily Israeli youth) and the world at large would encounter a figure who had heroically resisted, thwarted, and ultimately overcome the Nazis’ grand and evil designs and whose survival against all odds symbolized the rebirth of the entire Jewish people. And of the many who perished before liberation? They were now to be seen as having died fighting—“not on their bedraggled knees but on their blood soaked feet.”19 Writing some years after the trial, Hausner described the transformation of individual and collective identity that took place over the course of the proceedings in terms that clearly vindicated the past while also authorizing the nation’s political future:

It came as a discovery to many that we are actually a nation of survivors…. The trial … brought home to everyone in Israel the basic facts and lessons of our time. But even more significant was the feeling of self-assurance and confidence that swept the nation. If Hitler, for all his fiendish powers, enormous resources, and unrelenting efforts, did not succeed in wiping out Jewry when he had it at his mercy, then the age old belief in the eternity of Israel was reaffirmed before our very eyes. The Jews had survived their mightiest enemy. The prophetic assurance bequeathed by Isaiah to the Jewish people—“No weapon that is formed against thee shall prosper”—was once again proved true. In comparison with Hitler’s might the present-day anti-Semitics and foes of Jewry and of Israel, formidable as they may be, still look less menacing. There can be no complacency in facing them, but there is a valid and reasonable hope of overcoming them…. [T]he great national disaster has … been a fountain of new strength, and it holds out new hope for a better future.20

Nowhere on the ambitious, multivalent agenda that Hausner and Ben-Gurion set for the trial was there r...