![]()

Part I

Cosmopolitan Desires

![]()

1

Salir Adelante

Mobility, Travel, and Aspirational Economies in the Central Andes

Modernity is what it is—an obsessive march forward—not because it always wants more, but because it never gets enough; not because it is more ambitious and adventurous, but because its adventures are bitter and its ambitions frustrated. The march must go on because any place of arrival is but a temporary station.

—Zygmunt Bauman, 1991

The contrast of the country and city is one of the major forms in which we become conscious of a central part of our experience and of the crises of our society.

—Raymond Williams, 1973

Postulantes de loteria de visas acuden a cabinas de Internet en mancha. [Visa lottery applicants storm the Internet cafés en masse.]

—Ojo, 2003

In June 2004, when I arrived in Peru to start my dissertation fieldwork, the country seemed on the surface to be recovering rapidly from the deep internal political crisis that led to the implosion of the Fujimori regime in 2000. President Alejandro Toledo—or el Cholo Toledo, as some Peruvians liked to call him—was now three years into his term. The Peruvian economy had reached one of the highest growth rates in Latin America at the time, inflation was reduced, and the deficit was at an all-time historic low (Gonzalez de Olarte 2007). Democracy had been restored and the Peruvian congress was debating the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report of recommendations for institutional reform and a comprehensive reparation program for the victim-survivors of the violent conflict between the Maoist guerilla Sendero Luminoso and the Peruvian state that had plagued the country for close to two decades.1At first glance Peru seemed to be on a fast track toward a new era in its social and political life.

Yet there is always more than meets the eye. The national media reported weekly, if not daily, about Peruvians leaving the country in growing numbers. A few weeks before my arrival in the field in 2004, the largest national newspaper, El Comercio, had published an opinion poll based on a survey conducted in Lima, which showed that 74 percent of young Limeños would migrate abroad if they could and 53 percent had concrete plans to migrate in the near future.2 Scholars, politicians, and the national media at large participated in the production and circulation of an alarmist discourse of mass exodus, citing endless statistics of how many Peruvians had left that week or that month, and how many were likely to leave in the near future. Media images and popular culture references to people fleeing the country had circulated widely, perhaps not surprisingly, during the worst years of political violence. But why, now that Peru had supposedly become more economically stable and was generally safer for the average citizen, were images of exodus still so prevalent?

The panicky discourse about continued mass exodus in 2004 was not without material basis. Peruvians did in fact continue to migrate internationally in skyrocketing numbers throughout the first decade of the new century despite the country’s economic upturn, much applauded by both economic analysts and the international community. The answer to this apparent paradox is to be found in the processes of network expansion that accompany most migration flows and, once established, make them self-perpetuating over time (Massey et al. 1993). Based on data from the Latin American Migration Project (LAMP), scholars have argued that whilst a decent paycheck that could sustain a family was still readily available to most people in Lima under the regime of import substitution industrialization (ISI), this scenario changed after the introduction of structural adjustment policies in 1987 when both secure employment and wages fell dramatically (Massey and Capoferro 2006).3 Between 1988 and the early 2000s, more and more families in the capital responded to the economic dislocations produced by neoliberal economic policies and to the climate of violence and insecurity and relied increasingly on connections abroad to diversify their household income through international migration (Massey and Capoferro 2006). As a result, the number of migrants augmented dramatically post-1987, as did the variety of foreign destinations and the diversity of migrants’ regional and class backgrounds (Takenaka et al. 2010).4

While it is clear that the social, economic, and political transformations that accompany the expansion of markets along with the enduring effects of almost two decades of political violence produced the ongoing migration flows from Peru throughout the early 2000s, migration studies that approach human mobility merely as a brute fact that can be observed, measured, and analyzed, while valuable in their own right, are less useful for understanding mobility as embodied practice imbued with meaning that is historically variable.

The operative principle in Lima at the beginning of the new millennium indeed seemed to be sálvese quien pueda, an expression that roughly translates as “every man for himself” (Durand in Massey and Capoferro 2006:126). But it was not only in Lima that Peruvians were looking to abandon ship. In the central highlands where most of my Peru-based fieldwork took place, many people I talked to—young and old, men and women, rural and urban—were also contemplating the possibility of migration to foreign destinations. They talked incessantly about their desire to leave and articulated this aspiration by evoking expressions like “getting ahead” (salir adelante) and “improving oneself” (superarse); terms that are simultaneously classically Peruvian and utterly neoliberal in their implication of bootstrap performativity.5 Even Peruvians who had relatively stable jobs in local government offices in Huancayo or Jauja or owned small businesses were on the lookout for migration opportunities to foreign destinations which they hoped could put them on track toward greater future prosperity.

This chapter discusses how people in the Mantaro Valley and in Lima imagined migration to foreign destinations and what it meant to them. I suggest that these imaginaries are not unrealistic fantasies but are grounded in a broader history and political economy of travel, exchange, and expanding infrastructures that continue to shape the contemporary circulation of people, money, ideas, and cultural forms within and beyond the central highlands. This history is significant not only because it has shaped the identity of the Mantaro Valley as a particularly modern and prosperous region within Peru with a unique and vigorous popular culture (Romero 2001), but because it has produced shifting ideologies of mobility that in turn shape the production of contemporary mobile practices. To illustrate how present-day transnational migration operates within this broader history of Andean circulation, modernity, mobility, and travel, I discuss the migration histories of two young women, each from a different town in the area: Inés from Matahuasi and Domitila from Urcumarca. By examining the migration histories and experiences of women like Inés and Domitila and other migrants like them, I show that transnational mobility is variously imagined, experienced, practiced, and corporealized in contemporary Peru, but never inseparable from long-standing moral and cultural imperatives about class mobility which are exemplified in expressions such as “getting ahead” (salir adelante) and “improving oneself” (superarse).

Anthropologists working on issues of poverty, education, and race/class mobility have noted that expressions such as “salir adelante” were often linked to education in Peru and elsewhere in Latin America. For most of the twentieth century education was viewed as the main strategy through which the indigenous population could escape poverty, reduce racial discrimination, and achieve social mobility (De la Cadena 2000; Leinaweaver 2008; Malkin 2004). Jessaca Leinaweaver, for example, describes how concepts such as “getting ahead” and “improving oneself” operate in the context of child circulation in the southern highlands of Peru, that is, the practice of moving children between households and placing them where parents think they will have the best life opportunities. Here, as in the context of rural-urban migration more generally, these expressions immediately evoke the class position that one should aspire to move out of, and therefore impose on poor people, an ideology of self-improvement that they must claim as their own if they are to escape poverty (Leinaweaver 2008:60). This moral connotation attached to the concept of “improving oneself” should be seen in a relational context; in fact, it only fully makes sense when evoked in the context of the family or the community where the notion of “self” refers to more than the individual and includes close kith and kin.6

This prevailing ideology of self-improvement through education as a means to get ahead in life is now increasingly intersecting with processes of transnational migration. Indeed, in some cases, as Inés and Domitila’s stories will show, a key motivation for migration, especially for migrants who are a little older and have dependent children at the time of their migration, is either to be able to pay for a child’s education in Peru (Domitila) or to eventually send for one’s child or younger siblings to offer them an education abroad (Inés). Like education, transnational migration as a strategy for individual and familial progress and social mobility is imbued with hope for change and transformation; indeed, it is sometimes imagined as being capable of lifting entire families out of the shackles of poverty, immobility, and rural backwardness still largely associated with the Andean highlands and with Andean migrants in the capital and abroad.

Aspiring migrants in the Mantaro Valley had good material basis for imagining transnational migration as a stepping stone to a future full of possibilities. Many were already members of transnational migrant households and received monthly monetary remittances in U.S. dollars or Euros, birthday gifts, frequent phone calls, video letters, and home videos burned onto DVDs, from family members in the United States, Japan, Italy, Spain, or other countries. Simultaneously, they were returning photos or videos of home improvement projects and growing children left in their care and occasionally they shipped boxes with local food items, religious paraphernalia, handicraft souvenirs from the area, and DVDs featuring musical performances by local or regional artists. They also frequently visited Huancayo or Jauja’s many Internet cafés, the characteristic cábinas publicas found on every street corner, to connect with their relatives in other countries or to work on getting their own mobile projects off the ground.

The circulation of people, goods, money, ideas, and images across space is facilitated by and indeed largely depends on both older and more contemporary forms of physical, digital, and electronic infrastructures. Brian Larkin has noted that infrastructures as physical form “comprise the architecture for circulation, literally providing the undergirding of modern societies” (2013:328). Larkin draws on media theorist Armand Mattelart who has argued that all ideas of progress from the Enlightenment and in liberalism are based on representations of a world in movement, a world where the free flow of ideas and goods is unrestrained by the fixed hierarchical relations that had characterized feudal society (Mattelart 1996 in Larkin 2008:58–59; cf. Cresswell 2006). But for such movement to exist, Larkin notes, “it requires the constitution of technical systems of canals, roads, railways, and telegraphs, which create the material channels through which movement can occur” (2008:58). Understanding the longue duree of travel and mobility in this particular Andean region thus similarly requires attention to the changing infrastructure that has facilitated such movements over time and helped produce shifting representations of mobility, which in turn has shaped and continues to shape the production of mobile practices, including migration, in this part of Peru.

Routes, Travel, and Infrastructure in the Production of Andean Mobility

While infrastructures and the possibility of exchange over space that these enable are typically associated with industrial technological systems of the nineteenth century, they are not exclusive to modern societies.7 From precolonial times, Andean livelihoods were based on spatial mobility and complex but well-integrated production, distribution, trade, and exchange systems were fundamental to connecting the highland communities with the coast and the jungle lowlands toward the eastern slopes of the Andes. Scholars have shown that forms of spatial circulation including transhumance, differentiated and seasonal agriculture, barter, and trade allowed most Andean populations to earn sustainable livelihoods under changing political and economic circumstances, climatic uncertainties, and shifting pressures and demands of the precolonial and later the colonial state (Cook 1990; Golte 1980; Mayer 2002; Rostworowski de Diez Canseco 1999). These spatial practices allowed populations in the Andes not only to meet their subsistence needs by controlling access to as many microclimates, altitude levels, and ecological environments as possible (Cole 1985, Condarco [1971] 1987), but also to develop the powerful centers and infrastructures of ancient Andean civilizations, which in turn relied on complex transfers and control of labor flows and resources as well as an extensive road and communication system (Murra [1972] 1987).

The most powerful of the Andean civilizations was the Inca Empire.8 In the central highlands, the native inhabitants, the Wankas, had been subjugated to the Inca rulers who from around 1460 had disciplined regional chieftains into complying with their imperial policies (Espinoza Soriano 1973:68). Scholars have suggested that the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores to the area thus represented an opportunity for the Wankas to rebel against their Inca oppressors by becoming allies of the Spaniards. Some argue that this initial alliance is the reason why land in the Mantaro Valley—in contrast to other areas of the Andes where the Crown granted the colonial encomenderos or corregidores both land and the right to the labor of the Indians living on it—remained largely in the hands of the local population throughout the colonial period as a reward to the Wankas for their alliance with and loyalty to the Spaniards (Arguedas 1975; Espinoza Soriano 1973; Romero 2001).

Despite this early alliance with the Spaniards, the region suffered deeply from the devastating effects of the European invasion. Like the rest of Peru, the central highlands underwent dramatic demographic and social changes throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and historians have documented the way sweeping epidemics and out-migration of the population to participate in mita labor service, road construction, and the building of churches and reducciones towns profoundly changed the demography of the area (Mallon 1983; Stern 1982). This was further accentuated by the influx of population to work in the obrajes—the colonial equivalent of today’s sweatshops. Historian Florencia Mallon has found that already by 1780, this region had one of the highest percentages of mixed-race population in the Viceroyalty (1983:11).

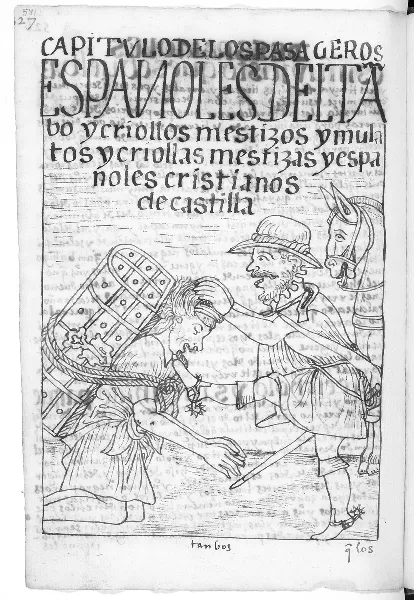

The colonial regimes of governmentality that attempted to fix and confine the Indian population in the reducciones towns (except when they were drafted to work for the colonial administration) not only transformed older Andean practices of spatial mobility to gain access to as many ecological environments as possible, but also gave rise to new forms and shifting meanings of mobility. Within the place-based logic of the reducciones, the Indians who became (or remained) mobile came to be seen as existing on the margins. According to Mörner (1985), some tried to escape their Indian status and its corresponding fiscal responsibilities simply by leaving their assigned communities and adopting Spanish speech and customs elsewhere. This was possible, for example, if they settled and registered as yanaconas (“helpers/dependents”), forasteros (“strangers/foreigners”), or even mestizos in a Spanish town, or if they entered the service of a landowner or miner as a peon (day laborer).9

Furthermore, as Saignes has shown, indigenous women in the Andes speculated on the future status of their children by registering them as illegitimately born to bypassing muleteers or llama-drovers (arrieros), thereby exempting their children from future tribute and labor obligations (Saignes 1995:184; Bouysse-Cassagne and Saignes 1992). These strategies for avoiding taxation and abuse from colonial authorities and taking advantage of the opportunities for social mobility and differentiation made possible through alliances with the Spaniards have frequently been interpreted in Andeanist scholarship under the rubric of resistance to the imposition of colonial rule. Luis Miguel Glave, for example, has argued that what before the conquest was a reproduction strategy (i.e., displacing the population to adapt to a rational use of space) had become “a movement of diaspora which manifests tactics of resistance to the colonial pressure” (Glave 1989:18; my translation). An exclusive focus on resistance, however, precludes an understanding of the aspirations and social agency of Andean societies and the often dynamic relationship between the colonial and indigenous society (Spalding 1970).

After independence in 1821, the control of mobility came under the purview of the new nation-state. The newly minted citizens could now at least in theory move without seeking permission, yet mobility was still organized along the lines of race, class, and gender and across the national territory. Social and economic stratification increased toward the end of the nineteenth century where new market and exchange opportunities gave rise to a new class of traders and town-based landholding mestizo elites (Adams 1959; Alberti and Sánchez 1974; Long and Roberts 1978; Mallon 1983). Peasants in t...