![]()

SECTION 1

ANC MOVEMENT-PARTY IN POWER

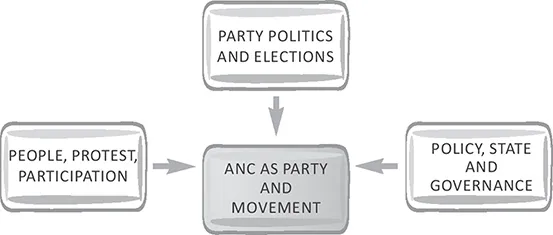

The ANC’s power project is anchored in the organisational strength that this movement-party carries forward into its relationship with the people, its electoral performances vis-à-vis the other political parties, and the governance project in terms of which it exercises state power.

Organisationally the ANC is a formidable force. In many respects, politically, the movement-party is also a world of its own. Internally, it is frequently wracked by power contests, dissent and policy-ideological contestation, with or without the motive to use ideas in the quest for position, succession and hence control over the levers of power. The ANC acknowledges its weaknesses of careerism and pursuit of individual power and prestige rather than unambiguous commitment to selfless service – which would be in line with the overwhelmingly noble character of the ANC as liberation force. The ANC towards 18 years in power had become a vastly changed organisation from the one that waged the anti-apartheid liberation war. Yet, despite its weaknesses, its internal wars (often substituting for inter-party challenge) and its complex policy-ideological positioning, it remained the strongly dominant (and only modestly declining) party political force in South Africa.

Section 1 takes stock of the overall paradox of ANC power and its paths into and in political power (Chapter 1) and the Polokwane-towards-Mangaung contests for internal power (Chapter 2). It explores the Tripartite Alliance and the strengths and vulnerabilities it brings to the ANC. It links the alliance contests to the ANC Youth League (ANCYL) quest for centre-of-power status. The section demonstrates how the ANC regenerates power internally. The processes sometimes happen in flawed and manipulated ways, yet combine with movement character to render a continuously legitimate and popularly endorsed organisation that remains in a league of its own. The overall thrust of this section is that the ANC’s project of sustaining and regenerating its own power has entered a phase that is different and distinctly more uncertain than it had been in previous eras. The ANC remains powerful, and projects itself as the tested liberation movement government. Yet, it is a distinctly different organisation, increasingly driven by new types of cadres that pursue scaled-down dreams.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: ANC pathways to claiming, consolidating and regenerating political power

The African National Congress (ANC), more than 17 years after political liberation, is hard at work to ensure that it rules ‘until Jesus comes again’.1 It is working hard to make the ‘heaven’ of persistent ANC power happen. It works to continuously regenerate its power, thereby ensuring that post-liberation South Africans continue believing that their future and fortunes lie with the liberation movement-party. Without such processes, the ANC’s still-formidable power base is likely to suffer far-reaching erosion. As this book argues, the ANC de facto or systematically by design has been working to contain its post-peak losses of power.

In the 2011-12 conjuncture the ANC has retained the bulk of its liberation movement appeal. South Africans carry deep scars inflicted by apartheid, racism and colonialism. The ANC is the symbol of their liberation. Opposition parties might have rationally-valid appeals, highlighting alternatives to ANC lapses and ANC government deficits. However, the people still retain a deeper linkage to the ANC, one that is cultivated both in the form of an electoral majority and through the ANC nurturing direct and powerful bonds with the people.

There is no guarantee that this deep and presently still pervasive ANC-people bond will persist. The ANC works to avoid a Zimbabwe-like situation at all costs, one where the popularity of the former liberation movement is eclipsed by new alternatives. In this the ANC has been acting pre-emptively to avoid a situation where there is a dangerously narrow margin between the governing liberation movement-party and any opposition party. To do so it works continuously on all fronts to regenerate political power peacefully, by all means legally and constitutionally available. Its democratic integrity is unlikely to allow it to turn to Zimbabwe style violence on its own citizens. Its insurance is precisely to work systematically to defend and nurture popular support, and the power that such support leverages.

Through this carefully steered project the ANC has largely managed to reproduce its power-status across the four domains – ‘faces’ of political power:

•of movement-organisation;

•in relation to the people;

•as competitive political party formalising power through elections; and

•as party in command of most of the state.

The result hitherto is that the ANC has been largely unchallenged by other political parties. Yet the period since 1994 bears testimony to modest threats to this position and flaws in the ANC’s armour. There is evidence of the ANC having moved beyond previous peaks in political power. Retreats in proportions of voter support across the provinces (in both 2009 and 2011 in all provinces except KwaZulu-Natal), cynicism about prospects for improvement in government performance, its ethics in government and in engagement in profit-making enterprises, and rising societal inequality in the face of enrichment of a new elite illustrate spectacular flaws. However, a critical marker of the current epoch is that the electorate has not abandoned the ANC. Rather, people have continued voting for and generally endorsing the ANC, often despite doubts and recognition of its flaws.

Most seriously, divisions and contests centring on factions mobilising for intra-ANC and intra-government power wrack the ANC internally. Intra-alliance contests contribute to what often appears as internal free-for-all combat. The ANC Youth League (ANCYL) acts as an internal guerrilla force, a de facto fourth member of the alliance, trying to hold the top leadership to ransom through the threat of its king-making power and imputed custodianship of the new generation of voters that holds the key to party political fortunes. By 2011, and operating in conditions of the ban on campaigning for ANC succession at Mangaung in 2012, the battle of the vanguards took hold. The South African Communist Party (SACP) and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) locked horns with the ANCYL over the position of vanguard of the poor and the workers. Even this debate was burdened by suspicions about motives and which business interests were being safeguarded in the name of being the torch bearer for achieving the (substantial) outstanding revolutionary transformation of South Africa. In this battle for the heart and leadership of the ANC, the SACP was backing Jacob Zuma as potential guarantor of its continuous hold on the position of ANC secretary general. Cosatu was playing a delicate balancing game, with Zwelinzima Vavi veering between taking on the role of top internal opposition to the ANC, and retaining intra-Cosatu legitimacy.

These internal processes distract the ANC from unambiguously devoting its attention to government and the project of state governance. Progress in government and policy is undisputed, but is often overshadowed by far too modest progress in the triad of issues of poverty, unemployment and inequality. More populist forces, often driven by the ANCYL and executed through demagogy and basic instinct policy options, suggest more extremist routes, perhaps to garner hope among young South Africans that new policies will achieve more definitive differences, perhaps to map their own routes into patriotic capital.

In cadre circles on the ground the ANC has battled to retain control over deployment in the face of cabals that have worked to secure political and economic power through local government and ANC branch mobilisation. The ANC-in-government engages in serial institutional redesigns and cadre redeployment to help keep hope alive. It often reports progress in terms of anticipated and ongoing action, rather than specific results and definitive turnarounds. It adopts moral stances and takes dipstick actions against transgressors of ethical codes of government, whilst stopping short of actions that would ‘indisputably root out’ these practices. This is combined with provincial and local government institutions and governance operations that fall far below the standard set by national government, which itself is often found lacking.

The epoch from 2010 onwards has lacked the euphoria, high optimism and unadulterated faith of people in the ANC, which characterised much of the first decade after liberation. The second decade was no longer one of automatic belief by a large proportion of the population that, given time, more change would come their way. Community protests, especially from 2004 onwards, signalled that people wanted action to supplement voting and ensure that the train to a better life would indeed stop in the local station. A political culture emerged in which large proportions of...