![]()

Protein

Maughan RJ, Burke LM (eds): Sports Nutrition: More Than Just Calories – Triggers for Adaptation.

Nestlé Nutr Inst Workshop Ser, vol 69, pp 97-113,

Nestec Ltd., Vevey/S. Karger AG., Basel, © 2011

______________________

Effect of Protein, Dairy Components and Energy Balance in Optimizing Body Composition

Stuart M. Phillipsa · Michael B. Zemelb

aExercise Metabolism Research Group - Department of Kinesiology, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada; bThe Nutrition Institute, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN., USA

______________________

Abstract

Weight loss is achieved through the consumption of a hypoenergetic diet and/or increased energy expenditure through exercise. While weight loss is associated with numerous benefits, the pattern of weight loss in terms of body composition changes is not always studied. In our view, the optimum pattern of weight loss is one in which fat mass is lost and lean mass is preserved. The preservation of lean mass has important consequences due to the role of this tissue in contributing to basal metabolic rate, controlling glycemia, and contributing to lipid oxidation. We also propose that a preservation of lean mass would have important consequences in resisting weight regain after loss. We review dietary practices, including reduced consumption of dietary carbohydrate, consuming higher than recommended dietary protein, with an emphasis on dairy sources, as well as dietary calcium, to accelerate the loss of fat mass during dieting and preserve lean mass. Available evidence suggests that each practice has a highly plausible mechanistic and growing clinical rationale in terms of efficacy in promoting fat mass loss and lean mass retention during a hypoenergetic diet.

Copyright © 2011 Nestec Ltd., Vevey/S. Karger AG, Basel

Introduction

Obesity and leanness are complex genetic traits, with multiple genes interacting to modulate energetic efficiency, including regulation of lipid storage in adipose tissue and lipid oxidation in support of new protein synthesis in skeletal muscle. However, the metabolic pathways operated by these genetic factors may also be modulated by specific nutrients, foods or dietary patterns, providing opportunities for functional foods and ingredients to alter body composition independently of their energy content. Weight loss, however, must depend on either reducing habitual energy intake or/and increasing habitual energy expenditure, or some combination of these two options. Many studies have shown the benefits of both approaches alone and in combination to promote weight loss, favorable blood lipid changes, better glycemic regulation, and a host of other benefits. Nonetheless, the longest-term studies on the efficacy of diet-only weight loss programs have reported that most participants regain their lost weight and continue on an upward trajectory in terms of weight gain [1]. A registry of what have been termed ‘successful long-term weight losers’ is now maintained and characteristics of those people are being examined [2, 3]. This review will assess the efficacy of certain dietary practices, alone or in combination with programs of exercise, on people’s capacity to lose weight and more importantly to affect the pattern of weight loss in terms of body composition. The focus on body composition is important because loss of lean as well as fat mass will have both short- and long-term consequences that may affect a person’s capacity to regain weight and affect their metabolic health. The focus of this review is on patterns of dietary macronutrients that appear, at least in short-term studies, to be more effective in promoting loss of fat mass and promoting lean mass retention. We also review the components enriched in dairy, such as calcium, vitamin D (when present as a supplement) and leucine, as important factors in promoting fat mass loss and lean mass retention or accretion.

The relative energy deficit created by dietary energy restriction and/or increased energy expenditure is clearly the primary driver of weight loss, but certain patterns of macronutrients and ingredients might create a generically applicable efficacious approach to weight loss. Dietary patterns may affect the rate and composition of weight loss; however, our recommendations extend beyond the energy deficit. In this review, we focus on weight loss strategies that affect not only the quantity of weight loss but the ‘quality’ of weight loss. An improved quality of weight loss is defined as being the loss of weight with the highest possible ratio of fat to lean mass loss with the further aim to promote loss of as much visceral body fat as possible. We propose that this weight loss pattern is important for short and long-term metabolic health and possibly aids in resistance to weight regain after loss [4-6]. The measurement of weight loss without focusing on the loss of skeletal muscle as a highly metabolically active tissue is flawed. Skeletal muscle is the largest single contributor to basal metabolic rate (BMR) [7] and its loss during a hypoenergetic period is therefore one of the main reasons why BMR declines with weight loss [8]. A decline in BMR will affect the acute reduction in weight loss and the long-term maintenance of a lower body mass. Weight loss resulting from reduced energy intake will lead to loss of skeletal muscle, which is unlikely to be reclaimed in the absence of resistance exercise to stimulate muscle hypertrophy, resulting in a chronic decline of BMR [9]. Moreover, skeletal muscle is the primary site of postprandial blood glucose disposal [10], and thus plays an integral role in regulation of glycemia and risk for type 2 diabetes [10]. Also, due virtually entirely to its mass, skeletal muscle is a significant contributor to lipid oxidation and thus is an important contributor to postprandial lipemia [11] and overall blood lipid regulation [11]. In the light of these roles of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, it is apparent that weight loss strategies need to protect against loss of skeletal muscle and promote fat, especially visceral fat, loss.

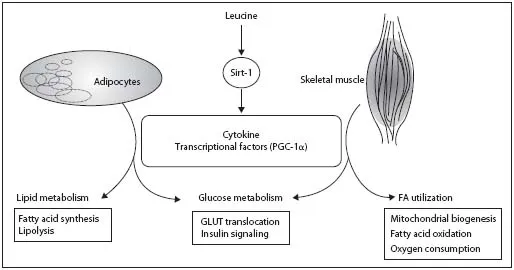

Fig. 1. Effects of leucine on energy partitioning between adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. Leucine stimulates Sirt 1 transcription and activity, resulting in reduced lipid storage and a net increase in lipolysis. Sirt 1 also mediates an increase in muscle mitochondrial biogenesis, fatty acid oxidation and oxygen consumption, and a net increase in insulin sensitivity. Based on data from Sun and Zemel [42].

Macronutrient Composition

The macronutrient composition of energy-restricted diets and the influence of these ratios on weight loss remain somewhat controversial. As recently as 2010 in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans the following conclusion was reached: ‘There is strong and consistent evidence that when calorie intake is controlled, macronutrient proportion of the diet is not related to losing weight’. (http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/DietaryGuidelines/2010/DGAC/Report/D-1-EnergyBalance.pdf). An important caveat in this conclusion, however, is in regards to the composition of the weight lost and the failure of the preceding statement to differentiate between the outcomes of subject compliance and diet efficacy [1]. The composition of weight loss with energy-restricted diets is generally 70-80% adipose and 30-20% lean tissue (almost exclusively skeletal muscle) [12]. As stated in the introduction, this pattern of weight loss will influence metabolic function during weight loss. The decline in BMR that accompanies weight loss is a primary reason for the slowed rate of weight loss seen in longer-term programs due to a gradual narrowing of the gap between energy requirement for weight maintenance.

Many weight loss diets set protein at 15% of energy, <30% lipids, and 50-55% carbohydrates, with reductions in dietary fat and increases in dietary fiber being favored. It is reasonable to reduce energy density with this ratio of macronutrients and promote weight loss in the short term, but this diet is associated with low satiety and poor long-term adherence [1, 13, 14]. Emerging evidence suggests that reducing the intake of dietary carbohydrates is critically important for promoting both greater weight loss and greater loss of body fat [13-15]. The mechanisms underpinning this effect are uncertain but may relate to a lower daily blood glucose and insulin levels [16]. Insulin’s primary function as a hormone is to promote storage of blood glucose in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue and to inhibit lipolysis and promote triglyceride synthesis and storage [16]. This may explain why a hallmark adaptation to lower carbohydrate diets is a pronounced reduction in circulating triglycerides versus other diets. A proven strategy, and one that is beneficial, is also to reduce not just the total quantity of carbohydrate but also to globally lower the glycemic load of the diet by selecting low glycemic-index (GI) carbohydrate sources [13]. In a weight loss context, such a strategy has been shown to be effective and also results in lowered insulin levels [16] and triglyceridemia [17]. It does need to be highlighted that following lower carbohydrate, lower GI diets may be a problem for endurance athletes seeking to compete since dietary carbohydrate intakes are recommended to be higher to allow full recovery of muscle glycogen stores. While lower total and relative carbohydrate diets appear effective, an important question is what macronutrient should replace the carbohydrate. Diets moderately high (no more than 35% of total energy intake) in protein and modestly restricted in carbohydrate (no less than 35% of total energy intake) and fat may have more beneficial effects on body weight homeostasis and associated metabolic variables [13-17]. Other factors such as dietary omega-3 fatty acids may also be important for weight loss given their impact on satiety and potentially on muscle anabolism. We focus here on moderate-protein diets (30-35% energy at the expense of carbohydrates) and those with low-GI carbohydrates (within the 40% energy).

Increasing protein to higher than the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) levels of 0.8 g protein/kg per day has a beneficial effect on retention of lean mass during hypoenergetic periods of weight loss [13-17]. In fact, in their meta-analysis, Krieger et al. [15] pointed out that in short-term trials (<12 weeks), protein intakes that were 40% higher than the RDA were associated with a 0.60 kg additional fat-free mass retention compared with diets with lower protein intakes. If the trials examined were extended beyond 12 weeks, then this difference grew to a 1.2 kg preservation of lean mass versus lower protein diets. The decrement in lean mass induced by a period of reduced energy intake can also be offset with a resistive exercise component to aid in muscle mass retention [18]. A small handful of studies have also reported that the combination of higher protein consumption and performance of exercise has a synergistic effect in terms of preservation of skeletal muscle mass [18, 19]. An important point is that such a strategy results in less total weight being lost, which may or may not be desirable. A few studies have shown that strength, for example, is preserved during periods of weight loss, and so a consideration for athletes is that if it is weight loss pure and simple that they require then preservation of lean mass may not be concern [20]. However, it i...