eBook - ePub

Tuberculosis and War

Lessons Learned from World War II

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tuberculosis and War

Lessons Learned from World War II

About this book

Tuberculosis (TB) remains the largest cause of adult deaths from any single infectious disease, and ranks among the top 10 causes of death worldwide. When TB and war occur simultaneously, the inevitable consequences are disease, human misery, suffering, and heightened mortality. TB is, therefore, one of the most frequent and deadly diseases to complicate the special circumstances of warfare. Written by internationally acclaimed experts, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the status of TB before, during and after WWII in the 25 belligerent countries that were chiefly involved. It summarizes the history of TB up to the present day. A special chapter on "Nazi Medicine, Tuberculosis and Genocide" examines the horrendous, inhuman Nazi ideology, which during WWII used TB as a justification for murder, and targeted the disease by eradicating millions who were afflicted by it. The final chapter summarizes the lessons learned from WWII and more recent wars and recommends anti-TB measures for future conflicts. This publication is not only of interest to TB specialists and pulmonologists but also to those interested in public health, infectious diseases, war-related issues and the history of medicine. It should also appeal to nonmedical readers like journalists and politicians.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Reflections about Belligerent Countries in Order of Appearance

Chapter 5

Murray JF, Loddenkemper R (eds): Tuberculosis and War. Lessons Learned from World War II.

Prog Respir Res. Basel, Karger, 2018, vol 43, pp 64–85 (DOI: 10.1159/000481475)

Prog Respir Res. Basel, Karger, 2018, vol 43, pp 64–85 (DOI: 10.1159/000481475)

______________________

Tuberculosis in Germany before, during and after World War II

Robert Loddenkempera · Nikolaus Konietzkob

aGerman Central Committee against Tuberculosis, Berlin, and bEssen, Germany

______________________

Abstract

In 1939, the year Germany started World War II, tuberculosis (TB) mortality was at its lowest, only a few countries had lower TB mortality rates. When the Nazis came into power in 1933, they took over under the main health-related motto “Public interest ahead of self-interest” (“Gemeinnutz vor Eigennutz”). In the first years, there was an intense discussion as to whether TB was caused more by hereditary disposition or by infection. Finally, the arguments by leading TB specialists were accepted that TB is predominantly an infectious disease. As TB mortality was increasing during the war in all sectors – in the civilian and military populations as well as among prisoners of war, foreign forced (slave) laborers and those in the concentration camps – multiple, partly inhuman measures for TB control were introduced, for example, compulsory isolation of so-called “anti-social” TB patients or even patients with infectious TB were forced to work. TB was one of the prevailing diseases in the concentration camps due to the crowded, filthy living conditions, and severe malnutrition. Overall, TB mortality increased by 160–240% compared with pre-war figures. With the help of the victorious Allied powers, the TB control system was restructured and the situation improved slowly over the following years.

© 2018 S. Karger AG, Basel

Germany started the Second World War (WWII) on September 1, 1939, with the invasion of Poland. As a result, the XIth Conference of the International Union against Tuberculosis (IUAT), which was due to be held in Berlin in the second half of September, had to be cancelled. In preparation for the conference, the Tuberculosis Committee of the German Reich (Reichs-Tuberkulose-Ausschuss [RTA]) had already had a booklet printed, entitled “The fight against tuberculosis (TB) in Germany” [Der Kampf gegen die Tuberkulose in Deutschland], which described the TB situation in some detail [1]. The “German Central Committee for the fight against Tuberculosis” (Deutsches Zentralkomitee für den Kampf gegen die Tuberkulose [DZK]), founded in 1895, had already been replaced by the RTA in 1933, shortly after the Nazi regime came into power in January 1933.

All non-governmental health organizations and scientific societies lost their legitimacy, and the government took over full responsibility under the main health-related motto “Public interest ahead of self-interest” (“Gemeinnutz vor Eigennutz”). This edict also changed the existing concepts of TB control in many ways as new control measures were decreed by new laws, as outlined below.

Tuberculosis before the War

Epidemiology

As described in chapter 1, death rates from TB peaked in Western Europe at the beginning of the 19th century, and then declined at a nearly constant rate for more than 100 years. A schematic model showing this trend of mortality from 1740 to 1985 is illustrated in Figure 2 in chapter 1 [2]. The challenges in the assessment of appropriate epidemiological data are described in detail in chapter 2.

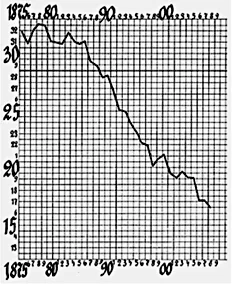

The development of the TB situation in Germany was quite similar. Figure 1 illustrates the development in Prussia after the discovery of the TB bacillus by Robert Koch in 1882. This figure is taken from his last presentation a few weeks before his death [3]. It shows an almost constant decrease in mortality between 1882 and 1907.

This decline continued over the following decades, and was only interrupted in the years of World War I (WWI; 1914–1918) and during the hyperinflation crisis (the Great Depression) in 1923–1924 (Fig. 4 in chapter 1 and 10 in chapter 2).

In 1939, the year WWII began, TB mortality was at its lowest level to date, at 60 per 100,000 population; by 1940, it had increased to 68/100,000. TB mortality in the Greater German Reich (Grossdeutschland), which included Austria and Sudetenland (part of Czechoslovakia) from 1938 after the annexation, was estimated in 1939 at 64/100,000 (and in 1943 and 1945 at, respectively, 80 and 100/100,000 [4].

In 1948, US TB specialist Esmond R. Long, who was appointed Head of a TB commission by the Secretary of the Department of the US Army, was asked to investigate the incidence of TB and recommend control measures in the German civilian population. He cites in his report:

Currency stabilization and resumption of a normal economic state in 1923, with ordinary employment and disappearance of some of the factors supposedly responsible for the 1922 rise in mortality, were accompanied by the development of one of the strongest TB control programs in the world. A nationwide system of TB dispensaries (Fürsorgestellen), a generous provision of sanatorium beds, an insurance system financing treatment of all social levels, and a centralized authority for maintenance of a control program (RTA) all had contributed to this success. Within Germany, excessive rates prevailed in a few places, like Berlin, but the national average compared with most other countries was low. [5]

The 1949 report of the US Commission came to the conclusion that “in 1939 only 4 countries – Denmark, Australia, The Netherlands and the United States – had lower TB mortality rates than Germany” [6].

However, in 1933, the speed of the annual decline in TB mortality had begun to slow down, from 73 to 60/100,000 in 1939. Between 1935 and 1937, an increase had been seen in 15–20 year olds: in males from 31.7 to 36.4/100,000 and in females from 43.6 to 55.5/100,000. Increased physical stress was assumed as the most likely explanation for the increase in this age group – in the newly founded youth organizations of the Nazi regime (Hitlerjugend [Hitler Youth] for boys and the Bund deutscher Mädchen [League of German Girls] for girls, and in the labor service (Arbeitsdienst), which was compulsory by law from 1935 for adolescents between 18 and 25 years of age [7]. Therefore, special regulations were decreed in 1938 to protect young workers (Erlasse zum Schutz jugendlicher Arbeitnehmer).

Fig. 1. TB mortality in Prussia, 1875–1907 (n/10,000) [3], with permission of Springer.

In 1938, the “Regulation on the control of communicable diseases” (Verordnung zur Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten) was decreed, sharpening the obligation to notify all new cases (and even suspected cases) of infectious pulmonary and laryngeal TB, TB of the skin, and of other organs. The registration of notified new TB cases (TB incidence or morbidity) was started throughout Germany already in 1934, and was discontinued only in 1943. In 1938, 65,866 cases of all forms of TB were registered (pulmonary 60,782, extrapulmonary 5,084). In 1939, these figures had increased to 80,798 (72,700 and 8,098) due to the annexing of Austria and the Sudetenland. Table 1 shows that in 1942–1943, the number of new notified cases had almost doubled compared to 1939, with a corresponding increase in incidence (Table 1). These numbers apply only to the civilian population; the military services had their own statistics [8].

Table 1. Annual new TB cases and incidence, Germany, 1938–1943 (from 1939 including Austria and Sudetenland)

Year | New TB cases, n | Incidence (n/100,000) |

1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 | 65,866 80,798 109,508 134,979 146,121 143,171 | 963 1,166 1,568 1,922 2,063 2,033 |

| Modified from Pöhn and Rasch [9]. | ||

Otto Walter, President of the RTA, estimated that in 1935 there were 300,000–400,000 open (infectious) TB cases (probably, largely sputum smear-positive cases, as culture was not yet routinely available), and more than one million persons at risk of becoming infectious. Approximately, 50,000 were entirely and 500,000 partly unable to work [10]. This caused a severe penury of workers, and measures were later taken to integrate most of these into the labor market (see below).

Pre-War Political Measures and TB Control Measures

Political Measures

After coming into power in 1933, the Nazi government issued a series of laws, decrees, and directives that affected the control of TB both directly and indirectly. As early as April 1933, the “Law for the Restoration of the Civil Service” (Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums) was passed, “a law that excluded anyone either of non-German heritage (Jews) or of questionable political sympathies (communists) from employment in the civil service” [11]. The most intrusive edict was the law for the “Unification of Health Affairs,” decreed in July 1934 (Gesetz über die Vereinheitlichung des Gesundheitswesens), which ensured that the health system came under almost complete control of the central government (Ministry of the Interior). By an executive order, most of the communal TB dispensaries (Fürsorgestellen) were incorporated into the local public health offices (Gesundheitsämter), thus transferring decision-making power to the central government, with potentially significant consequences for the individual TB patient.

The most intrusive laws for the individual were the “Law on the prevention of genetically diseased offspring” (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses), issued in July 1933, allowing the sterilization of persons with mainly psychiatric diseases, which was followed in 1935 by the “Law for the protection of the genetic health of the German Volk” (Marriage Health Law) (Gesetz zum Schutze der Erbgesundheit des deutschen Volkes [Ehegesundheitsgesetz]) [12], on the basis of which a marriage could be forbidden (or divorce allowed) when one of the partners suffered from an infectious (or mental) disease that could substantially threaten the health of the (future) spouse and/or potential descendants. Thus, before being married, both partners had to produce a certificate from the health office to the effect that there were no impediments to the marriage. In 1937, Julius Kayser-Petersen, Secretary General of the DTG, postulated that in almost all cases – except in the case of obviously infectious patients – an examination should be performed by a specialist and that in case of unclear results, the decision to allow the marriage should be postponed followed by careful observation [13]. It is not exactly known how many TB cases were affected by these and the corresponding decrees. In any case, there were many fewer than among psychiatric patients, many of whom were sterilized or even killed as terrible consequence of the Marriage Health Law and other, similar decrees. As cited by Susanne Hahn [14], the suggestion was made that women diagnosed with TB during pregnancy should have their babies taken away immediately at birth to allow them to grow up in a healthy environment [15]). In theory, therefore, termination of pregnancy was strictly prohibited. However, in practice, TB was in fact the most frequent medical indication for abortion [16].

The whole topic was connected to the debate as to whether certain diseases are of hereditary origin, an international debate which had already started at the turn of the century, stimulated by Darwin’s Law of Evolution by Natural Selection [1...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Front Matter

- Background Information about Essential Material

- Reflections about Belligerent Countries in Order of Appearance

- Conclusion

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- Back Cover Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tuberculosis and War by J. F. Murray,R. Loddenkemper,J.F., Murray,R., Loddenkemper, J. J. F. Herth,F.J.F., Herth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Emergency Medicine & Critical Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.