![]()

ONE

REDEFINING RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE RURAL WEST

TROPHY HOMES PERCHED ON MOUNTAIN SLOPES AND RIDGETOPS ARE an increasingly common sight in the West, the latest in a series of strategies that westerners have employed to control nature and capture wealth from the mountains. When developers platted the initial rural master-planned subdivisions in the 1950s, in many cases their work represented the first break from traditional, agriculturally sustained rural communities. These early planned housing developments offered structures that were more like cabins than suburban houses and had few amenities beyond natural aesthetics, and they were built at a time when rural counties had few building regulations and zoning requirements. The housing trend accelerated in the 1980s, when large numbers of people with greater financial resources started migrating to the mountains, lured in part by developers promising homes in the woods equipped with a full range of suburban amenities. Developer-packaged aesthetics drew a trickle and then a rush of homeowners away from the cities and suburbs—and into the wilderburbs.

Although it may appear that early twentieth-century ranchers and miners and late twentieth-century wilderburb developers had very different ideas about land use, both groups shared a common goal: they wanted to capitalize on mountain landscapes for profit. Early settlers relied on mineral wealth, soil productivity, and carrying capacity to support their herds, flocks, and livelihoods; they invested money and labor to profit from mines, ranches, and farms. Wilderburb real estate developers invested in the same land, but they seized on compelling viewsheds for gain. They built houses to lure buyers looking for a tranquility and beauty not found in traditional suburbs. To provide these aesthetics in an appealing consumable package, wilderburb developers had to imprint a sense of suburban order onto the land, rearranging many natural features in the process. Similar to a gardener reordering a patch of ground to produce a more pleasing scene, developers had to maintain a balance between the appearance of an untouched forest and the order and security of a garden. To attract homebuyers from distant metropolitan areas to the forest edge, developers seized on the landscape's irregular character. Far from being an obstacle to subjugate with bulldozers, irresistible “natural” viewsheds became the key selling feature.

As this housing trend became more popular and developers catered to homebuyers’ desires and market forces, new developments became more sophisticated. In the late 1950s residential developments leaned toward the uncultivated aesthetics that required little capital investment in infrastructure. By the 1980s, however, as people from urban areas with more money relocated to the mountains, the balance between wild forest and garden shifted toward the garden, with developers building golf courses, nature trails, and parks. The amount of capital needed to provide these amenities created much greater financial risk for developers. To sell homes and achieve financial success, they relied on a combination of scenic beauty, relative proximity to metropolitan areas, and the right combination of amenities and price to appeal to upscale homebuyers. The increased level of planning and development produced challenges for both the developers and the host rural counties. The wilderburbs ultimately created a novel landscape that appealed to homeowners’ changing attitudes about quality of life and nature, but this new landscape produced unintended consequences for both the land and landowners. Residential development in the mountains was far more difficult and complex than anyone had imagined.

PRELUDE TO WILDERBURBS

The first wilderburbs were not created at a precise time or date, nor did they draw inspiration from a dramatic event. Many factors induced homeowners to move out of cities and suburbs into houses in the woods. To understand the phenomenon, we must unearth its roots and see how cultural ideas, policies, and demographic shifts coalesced to affect how rural subdivisions evolved into the communities we recognize today. In the early nineteenth century, as Americans became more urbanized, some people began to seek in nature a counterbalance to and refuge from the perceived ill effects of city life. Some advocates pushed for the federal preservation of scenic areas and forests; others, such as Henry David Thoreau, sought to escape the city and live, at least part of the time, “deliberately” in the woods. By the early twentieth century these two cultural trends were working in concert with one another as small numbers of Americans looked for ways to acquire their own woodland retreat.1

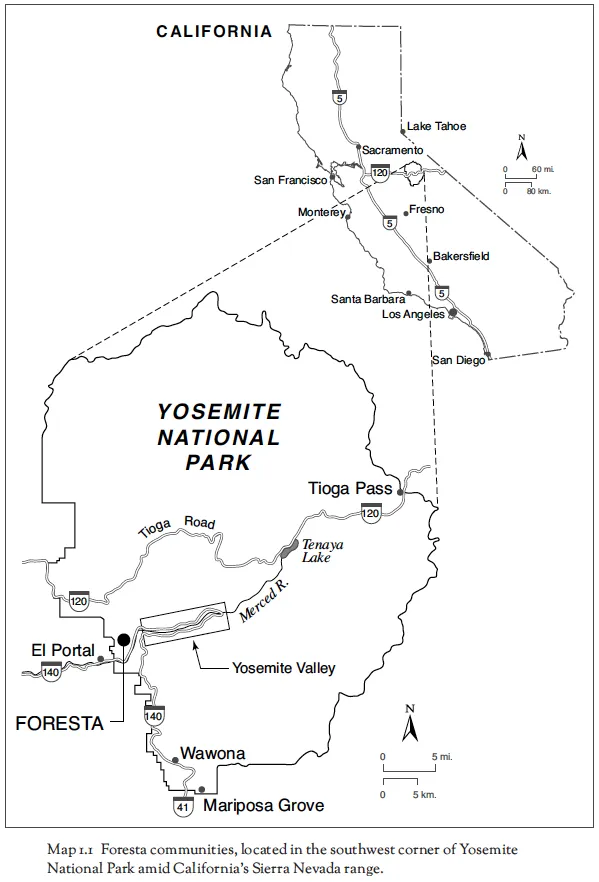

The 1915 Term Permit Act was an important beginning in the history of wilderburb development. As U.S. presidents declared or expanded national forests and parks, the newly designated public lands encroached or surrounded inholdings of private property. In many cases, these inholdings (formerly ranches or homesteads) gained legal protection under the Term Permit Act and remain in private hands to this day. Examples of this summer cabin phenomenon exist throughout the West, and their individual histories are almost interchangeable. The community of Foresta in Yosemite National Park is one of the most well-known examples of a homestead that transitioned into a summer cabin retreat that held on as a private inholding within a public land boundary. Foresta was created in 1911 in Big Meadow, a small valley not far from the venerated Yosemite Valley. Big Meadow witnessed the range of successive land uses that many western landscapes have experienced over the past century and a half. These uses moved from Native American subsistence settlement, to early Euro-American extractive enterprises, to federal land reservation and the creation of a public park, to privately owned summer cabin retreats, which created a market for the scenery.

Among the first inhabitants of Big Meadow, a group of Indians who identified linguistically most closely with the Southern Miwok occupied the area for at least seven thousand years before Europeans arrived, subsisting on the abundant game and black oak acorns they cached in elevated granaries called chuckahs.2 After the discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills in 1848, the influx of thousands of miners precipitated what became known as the Mariposa Indian War and the eventual expulsion of the tribe. On June 30,1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Land Grant Act, placing Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias under the stewardship of the State of California as an inalienable public trust.3 With the Indians removed and a tourist destination established, white settlers began to populate the nearby country. In 1873 a gold-miner-turned-rancher named Dick Meyer bought squatter's rights from a local Indian and became the first permanent Euro-American resident of Big Meadow.

A small group of settlers joined Meyer and filed for 160-acre homesteads that many of them later patented (converted into private ownership). Encouraged by preservationists led by John Muir, President Benjamin Harrison signed H.R. 12187 on October 1, 1890, which preserved fourteen-hundred-square miles around the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove.4 With the stroke of his pen, the president surrounded much of the Meyer ranch and several other original homesteads around Big Meadow with federally preserved land. Now surrounded by a public park, many of the homesteaders continued to work the land, raising livestock and growing foodstuffs to serve the burgeoning tourist traffic. At the same time, several of the old-timers began to sell off their land to developers. In 1911, Fred McCauley sold forty acres for fifty-five-hundred dollars to San Francisco developers, who subdivided the land into 233 postage-stamp-size lots. The investors named their development Foresta and inserted a restriction against any “obstruction to the view” in each deed.5

Foresta's investors made grand plans for the development. On October 23, 1912, they incorporated the Yosemite Utilities Company to provide infrastructure for the development; and although the company promised to “build, maintain, and operate a sawmill, waterworks, light, heat, and power plants,” these improvements never materialized. Months later, in 1913, the investors incorporated as the Foresta Land Company, envisioning Foresta as a place to foster high-minded literary and scientific thought. They organized the Foresta Summer Assembly to host public talks and lectures on the arts, nature, and philosophy. An advisory council was formed with speakers and thinkers, such as literary giants John Muir, Jack London, Joaquin Miller, and George Wharton James. Payment for their participation on the council consisted of a deed to one lot in Foresta. None of the bright lights except James attended a gathering or improved their lot. James became a summertime resident and an active booster of the development. The investors’ grandiose plans failed to attract a significant number of buyers, however; in large part, this was due to the site's near inaccessibility. By 1913 only thirty individuals had purchased lots in Foresta.6

The population in Foresta remained low, even after the completion of the All-Year-Highway (US 140) between Merced and Yosemite Valley unlocked automobile transportation to the park in 1926.7 Yosemite National Park's isolation, with access only by way of an arduous journey, protected it from Euro-American exploitation in the nineteenth century, but this remoteness also kept the Foresta development from reaching capacity in the twentieth century. Not until 1951 did Foresta experience a housing boom, when the Pacific Gas and Electric Company brought power lines to the development for the first time. Residents finally had power for lighting, refrigeration, and water heaters, and although amenities and conditions remained somewhat primitive; between 1951 and 1962 seventy-four cabins were built and a number of families resided in Foresta year-round. Around this time the National Park Service sent a shockwave through the community when it began a program to eliminate private property within the park. The nationwide Mission 66 program to rehabilitate park infrastructure and improve the visitor experience provided Yosemite with annual funds to purchase lots from willing sellers within Foresta and commit them to Park Service ownership. Just as Foresta began to experience growth, the National Park Service's campaign to purchase lots sent the message that the park wished to bring the site under public ownership. Consequently, this dissuaded many owners in Foresta from improving their lots.8

Although some absentee owners sold their Foresta lots to the Park Service, many continued to reside there at least part of the year. For these residents the community represented more than just a cabin; it brought connectivity to nature and was a refuge from the modern world and urban cares. In the words of one cabin owner: “Foresta is a state of mind, a solid core of refuge, beauty and peace where heart, spirit and body are content. It is beckoning woods in which to lose one's troubles and, maybe, one's self…. It is the real world.”9 The Foresta summer cabins and other summer cabin communities on public lands signaled the initial residential push into the woods, representing expanding ideas about how to use the land. These cabin retreats foreshadowed changes in the conservation movement as it slowly evolved from the pre-World War II conservation of efficient and moderate use of natural resources into a quality-of-life movement that sought to improve the daily lives of Americans. This movement became known more broadly by the 1960s as environmentalism. It took years for the changes in the conservation movement to materialize, however. Hard economic times and wartime rationing caused a sharp decline in visitation to national forests and parks in the West and curtailed much of the summer cabin development in these areas.10 Disposable income among middle-class Americans stayed at record lows during these decades; and even though many people took the time to picnic, camp, or vacation on public lands, most Americans did not have the financial resources to invest in even a modest woodland cabin.

With the end of World War II, everything changed. The United States entered an era of unparalleled economic growth. After decades of sacrifice and saving, depression and rationing, middle-class Americans in particular experienced prosperity again and readily embraced consumption. With little global industrial competition, U.S. manufacturing and agricultural exports rose sharply and the domestic market for goods and services opened up. Millions of veterans returned to work, and many attended college under the GI Bill, increasing their earning potential. Postwar initiatives like this helped to expand economic prosperity to a wider segment of society. Increased affluence brought enthusiastic consumption. Low unemployment, inexpensive gas for automobiles, and the new interstate highway system allowed Americans to live farther from the urban center and still work in traditional occupations. Growing access to capital and advances in prefabricated construction techniques, not to mention improved real estate marketing, drew people to the suburbs and city edges with promises of home ownership in what were considered spacious homes and large lots.11

According to historian Hal Rothman, the new consumerism of the 1950s meshed well with the changes taking place in conservation. Americans could develop land for housing, industry, and other uses while still considering themselves conservationists because “progress and the ethic of conservation were entirely compatible. Space was either sacred or profane, either reserved because of its special value or open to development.”12 This dichotomy of love for scenic nature, particularly for public lands that conservationists had fought so hard to preserve, and a willingness to develop land for personal consumption took shape alongside another reality. Among Americans in general there was a seemingly unconscious devaluing of working agricultural lands and other landscapes. Beyond the suburban edge, building a cabin or a home on undeveloped land altered the natural character that attracted the wilderburb homeowner; yet this contradiction in Americans’ value of nature became a hallmark of the new wilderburbs, mirroring a great shift in the conservation movement from the 1950s on.

Amid the economic prosperity after World War II, real estate developers identified and began targeting a small market of scenic beauty enthusiasts who sought a refuge away from urban and suburban areas but close enough they could access jobs and consumer amenities. Beginning with the early developments in the 1950s and continuing through the rest of the twentieth century, land developers built homes on the forest edge because they could market the land's allure and sell houses at a premium. In essence, they hoped homeowners would pay for much more than a home; they hoped buyers would also pay for the natural surroundings. The plan worked. Enough people wanted to live in the faux wilderness, in structures that resembled a suburban home more than a cabin, to make the developments viable for investors. This limited success signaled an elemental shift in rural land use across the Mountain West. Residents no longer extracted commodities from the land; they now tended and cared for it like a garden to preserve their postcard mountain views. Developers advertised this elemental shift in their sales brochures. In Colorado, promotions touted that well-planned, rural subdivisions offered “the dream of every individual. Far from the noise, confusion, and smog of the city, where life takes on a new meaning. Next to nature where children learn about life, breathe fresh air, hike through the hills, enjoy God and his creation.” Another advertisement promised that “families thrive in the clear mountain air where there is enough room to provide privacy for the home-owner, and give the ‘kids’ room to run, and leap and shout—'to their heart's content.’”13 Central to these brochures was untrammeled nature that provided privacy and inspired residents to delight in God's creation. The ads emphasized a different attitude toward the land, which was far removed from running cattle or drilling for minerals.

The first wave of large-scale planned residential developments in western mountain areas began in the 1950s. The children and grandchildren of the original ranching families sold their land to developers and launched subdivisions. Typical of this experience is the transformation of a former ranch into a subdivision in Colorado's Front Range, west of Denver. According to longtime area residents, the Fitzsimmons family had two sons who served in World War II, and when the young men returned, they had no desire to run the family ranch. Consigned to his children's wish to leave the ranch, paterfamilias Perry P. Fitzsimmons sold the land to Chester Howard, who quickly flipped it, selling it to brothers Fred and Walter Burke and their partner, Gil Weakland. The three combined their last names and formed the Burland Ranchettes development. In February 1957 the trio filed plats with the Park County Clerk's Office for the initial three construction phases in the new subdivision. Together, these three phases comprised 149 lots. Burland Ranchettes grew steadily as the original develo...