![]()

PART ONE

THE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE

![]()

ONE

Establishing Roots

Island soul of me

Cast off to cross the ocean.

Ah, the world is big!

—Issa1

ON A DRIZZLY LATE summer morning in 1919, the passenger freighter S.S. Suwa Mam nudged its hull against the pilings of a familiar berth at the Great Northern Railway pier in Seattle's Elliott Bay, bringing a collection of people and cargo from Asia. The ship, one of four British-built vessels owned by the NYK (Nippon Yusen Kaisha) shipping line, was completing the North American leg of the company's twenty-five-year-old route between Seattle and the Asian Pacific.

Shortly after the lines were secured, a first-class passenger, Dr. Toma Inoue of Tokyo, appeared on deck attired in a deep blue-black silk kimono with “a touch of white at the throat.” One of 500 licensed female physicians in Japan, Dr. Inoue had received her training in Western medicine, with a specialty in internal medicine and diseases of children. She was en route to New York at the invitation of the international YWCA to attend a conference on education in health and social morality. Following an interview with the press, the assistant manager of NYK escorted her off the ship for a tour of the city; his instructions from his superiors were to attend to her welfare during her twenty-four-hour stay in Seattle.2 The ship's passenger list recorded this as her sixth journey to America.3

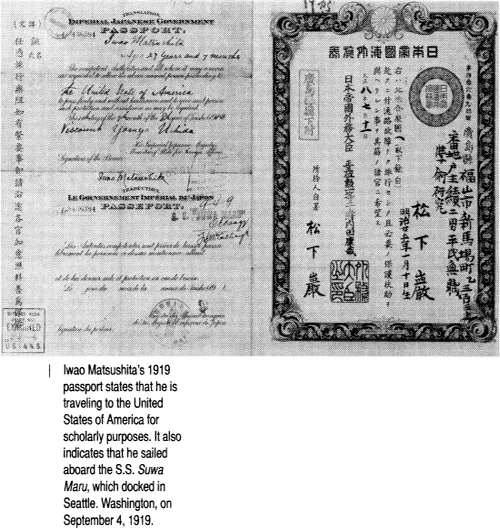

Among the 325 other passengers on board (233 of them Japanese subjects) were twenty-seven-year-old Iwao Matsushita and Hanaye Tamura Matsushita, his twenty-one-year-old bride of seven months. They had boarded ship at Yokohama, the last of several scheduled stops prior to the Pacific crossing. Although the majority of the Japanese passengers were returning to the United States, the Matsushitas, having booked one-way passage, were traveling abroad for the first time. They planned to make Seattle their home for as long as five years.

The year 1919 saw 10,064 Japanese immigrant arrivals in America,4 many of them came as sojourners with dreams of accumulating wealth to take back to the homeland for a better life. The Matsushitas also arrived with dreams of riches, but they sought a wealth of a different kind. Iwao's passport bore a student visa,5 which gave him entreé to a culture that would enable him to pursue fluency in the English language, to acquire familiarity with its literature, and, he believed, “to become a better man.”6

Iwao Matsushita was born on January 10, 1892, in Miike, Hiroshima-ken (Hiroshima prefecture), on the island of Honshu.7 He was the second son and third of five children of Isao and Hana Matsushita. A sister, Toku, and a brother, Sekio, were four and two years older. Sisters, Tonomi and Fumi, followed three and five years later. The Matsushita family members were among a minuscule group of people practicing the Protestant faith in Japan at that time. Earlier, following the Meiji Restoration, Methodist missionaries had converted the elder Matsushita to Christianity; he later became a proselytizer.8

Isao Matsushita's superiors sent him to engage in mission work in Tonomi, a small fishing village near the seaport town of Mitajiri. Immediately, the Matsushitas became a curiosity to the non-Christian villagers, a curiosity that quickly turned on the newcomers and led to persecution of the children. Spreading the word of Christ among a Buddhist majority proved burdensome enough for Isao, but the lives of the Matsushita children became unbearable after the parents enrolled the two eldest children in the primary school. Years later, as an adult, Toku revealed in her diary the story of her early persecution at the school:

A few days after our arrival [at] Tonomi, father took me to the primary school for admission. The teachers and children received us with looks of surprise. Many children at once crowded around and stared at us very wonderfully as if we Christians were visitors from a distant foreign country or rather something not human. Though I was able to pass my first day at the school without suffering any mischief because my father was with me, some mischievous boys would not let any other day pass without teasing me in some way or other. The very next day, some boys came near me and by turns pulled my hanging braided hair crying, “Why did you Christians come to this village? What did your family come here for? We guess you've come to destroy our Empire, you hateful foreign girl!”9

Despite the early cruelties suffered by each of the children, young Iwao's upbringing in a Methodist household exposed him to Western culture and awakened a keen interest in the English language, one shared by his parents and all his siblings.10 Following graduation from Kobe's Kwansei Gakuin high school in 1911, he entered the prestigious Tokyo Foreign Language College to study English language and literature. During summer breaks, his eagerness to learn led to employment at the British Embassy tutoring an attaché in Japanese. After three years of study in the Department of Education, he received a certificate to teach English in Japan's high schools. From 1914 to 1919 he drilled students in English grammar at a high school in Fukuyama, Hiroshima-ken. His principal there, Mr. Tamura, was the father of the woman who later became his wife.

Hanaye, six years younger than Iwao, was born March 9, 1898, in Okayama, Okayama prefecture, on Honshu Island. Her parents, too impoverished to provide for their children's basic needs, eventually turned her and her siblings over to an orphanage. In time a home was found for Hanaye. Her adoptive parents, the Tamuras, possessed sufficient means to support a child; they raised Hanaye in the Protestant tradition and sent her to a private Christian school in Tokyo for a portion of her education.

As was the custom, the Tamuras planned to arrange their daughter's marriage. The intention was to adopt a boy whom Hanaye would marry and who would eventually inherit the family property. The adoption took place; however, the marriage plan dissolved after the spirited young Hanaye balked. According to surviving family members, she simply did not like the boy and refused to go along. Therefore, at twenty she remained unwed. Still determined to find a match for their only daughter, Mr. Tamura turned to Matsushita, the eager and promising young English teacher at his high school. A traditional go-between helped arrange a match, this time successful, and a marriage took place on January 22, 1919. Hanaye viewed this relationship not only as an opportunity to be rid of her “brother” but also as the beginning of an exciting life with an educated man whose sights were beginning to focus eastward on America.

It is not clear when Matsushita first considered coming to the United States. Certainly his upbringing and professional interests influenced his developing vision, but his marriage to Hanaye also must have contributed. Dr. Kyo Koike, an old friend of Mrs. Tamura's whom Hanaye fondly called Uncle, the customary address for familiar elders, was a Seattle physician who had emigrated from Shimane prefecture in 1917. Koike's medical practice, which included surgery, was located in the heart of the city's Japantown, the Nihonmachi, where he served the immigrant population living there and in the surrounding farm communities.11 Longer established in Seattle was Katuichi Katayama, a relation of Koike's, who served the Japanese business community as an interpreter. These familial links led Matsushita to look to Seattle too, where the University of Washington might be the means of achieving his intellectual goals.

The encouragement of Katayama and Koike, the frugality that enabled Matsushita to save the necessary capital for a comfortable oceanic journey and adjustment period in America, and the adventurous spirit of a young wife led to passport applications and booking on a trans-Pacific steamer in the summer of 1919.

THE CROSSING

The Matsushitas arrived at Yokohama at least a week prior to the scheduled departure of the S.S. Suwa Maru for America in order to validate their passports and receive the obligatory medical examination. On August 12 they presented their papers to the American Consulate General. Iwao's passport stated the purpose for their travel to America—”for scholarly pursuits and research” (gakujutsu kenkyuu)12

On August 19 the ship slid from its berth in Yokohama harbor to begin the crossing, the trip having originated in Hong Kong and made stops at Shanghai, Nagasaki, and Kobe. Matsushita's savings enabled them to avoid the discomforts of third-class passage endured by many married couples and picture brides of that era. One third-class passenger who paid the $75 booking later remembered: “Of course the trip was third class, and there were miserable things about it. There were four people in one cabin with four small silkworm-type shelf-bunks. On the floor was cargo with canvas spread over it, and sitting on that we third class passengers had our meals.”13

Following sixteen days on the high seas and a twelve-hour stopover in Victoria, British Columbia, the Suwa Maru headed southward into Puget Sound. Hours later she entered Seattle's Elliott Bay. At 11:00 a.m. on Wednesday, September 3, under a pewter sky, the Matsushitas' trans-Pacific journey ended beside the long finger pier at Smith Cove, nestled between Magnolia Bluff and Queen Anne Hill. Adjacent to the pier another frequent visitor, the Azumasan Maru, awaited her scheduled departure date for the return voyage to Asia.14

Although the Matsushitas' passport status and ship accommodations made their voyage much less exhausting than most immigrants', it still took many hours to clear immigration and customs.15 Only the next morning were they able to leave the wharf and shuttle southward toward Japantown, likely under the escort of Katayama. Europeans of their status would have walked right through.

For the young couple, Seattle was part of a strategy for furthering Iwao's professional life as a teacher in Japan. They had no intentions of making Seattle their permanent home. Fate, however, would intervene. Hanaye would never return to her homeland, and neither one would see his parents again.

SETTLING INTO SEATTLE LIFE

The Matsushitas arrived in America with $450 in cash, an ample sum to tide them over for several months until they acclimated to the strange country. This amount far exceeded the traditional $50 per capita of most immigrants. With this cushion they could afford to rest for the first days or perhaps weeks without Iwao's having to seek immediate employment. They stayed with Katayama at his house for the first month, and there Matsushita met Koike, who had stayed with Katayama upon his own arrival two years earlier.16

Few immigrants spoke English adequate to facilitate adjustment into the mainstream. Seattle's Japantown provided a welcome transition. In 1919 the Matsushitas and their fellow passengers found 7,484 people there, 2.5 percent of the city's total population.17 The Nihonmachi extended some blocks from its business center at Sixth Avenue and Main Street, below Skid Road and south of the city's main downtown area. The area bustled with 1,489 business of all kinds.18 Japantown consisted of a mélange of small groceries, restaurants, apparel shops, barbers, dye works, and many other small operations serving the needs of arriving immigrants, resident Japanese, and nearby working-class whites as well.

Following their stay with Katayama and his family, the Matsushitas moved to their first housekeeping address, 1032 Main Street. This rental house was situated several blocks east of the heart of the Nihonmachi business district and faced southward toward majestic Mount Rainier, a fourteen-thousand-foot peak that would play a spiritual role in their lives in later months and years. Iwao soon found temporary employment as a cook in a Japanese-run restaurant.

An active community religious life awaited the couple, for both Buddhist and Protestant churches were well rooted in Seattle by the time of their arrival. The Japanese Methodist Episcopal church, which they soon joined, had its own permanent building on Washington Street.19 Their affiliation with the church (which later became Blaine Memorial Methodist Church) would bring them spiritual fulfillment throughout their lives.

The stay on Main Street and Iwao's career as a cook proved brief. On January 7, 1920, the census taker recorded the Matsushitas as on-site managers of the Chester Lodging House at 1322 Old Fifth Avenue (Fifth-and-a-Half Street).20 Eight working-class boardinghouses lined the two-block street, in reality a wide alley sandwiched between Fifth and Sixth avenues and hardly a legitimate thoroughfare. The Chester's thirty rooms earned it the reputation as the largest residence along the row.21 The lo...