eBook - ePub

Northwest Lands, Northwest Peoples

Readings in Environmental History

Dale D. Goble, Paul W. Hirt, Dale D. Goble, Paul W. Hirt

This is a test

Share book

- 560 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Northwest Lands, Northwest Peoples

Readings in Environmental History

Dale D. Goble, Paul W. Hirt, Dale D. Goble, Paul W. Hirt

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

It can be said that all of human history is environmental history, for all human action happens in an environment—in a place. This collection of essays explores the environmental history of the Pacific Northwest of North America, addressing questions of how humans have adapted to the northwestern landscape and modified it over time, and how the changing landscape in turn affected human society, economy, laws, and values. Northwest Lands and Peoples includes essays by historians, anthropologists, ecologists, a botanist, geographers, biologists, law professors, and a journalist. It addresses a wide variety of topics indicative of current scholarship in the rapidly growing field of environmental history.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Northwest Lands, Northwest Peoples an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Northwest Lands, Northwest Peoples by Dale D. Goble, Paul W. Hirt, Dale D. Goble, Paul W. Hirt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Forestry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 / Setting the Pacific Northwest Stage

The Influence of the Natural Environment

In no other part of North America is so much physical geographic diversity compressed into such a small area as in the three states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. And in perhaps no other part of North America has the natural environment had such a profound effect on human activities. The Pacific Northwest's 250,000 square miles—6.8 percent of the United States' total—hold towering volcanic peaks, raging whitewater rivers, sagebrush-studded volcanic plains, deeply incised canyons, wave-battered rocky coastlines, lush agricultural valleys, and nearly impenetrable coniferous forests. In a half-day's drive from Spokane to Seattle, La Grande to Portland, or Boise to Coeur d'Alene, one experiences tremendous environmental diversity. The climate, landforms, flora, and fauna change repeatedly and remarkably in a mere two or three hundred miles.

On this varied natural stage we humans have settled the land. In the process, we dramatically changed it. We cut the trees, dammed the rivers, paved the pathways, plowed the prairies, dug up the minerals, and turned loose the cows. Our efforts made deserts verdant, turned rivers into reservoirs, reduced mountains to hills, erected cities and towns, and generally “tamed” the wilderness. American history is full of heroic accounts of people “conquering nature,” “opening the frontier,” and “developing natural resources.” Testifying before Congress in 1828, unabashed Oregon booster Hall Jackson Kelley described the territory as “the most valuable of all the unoccupied parts of the earth.” The remaking of nature was our manifest destiny—and certainly the Pacific Northwest fits this frontier model.

The diaries of explorers such as Captain James Cook, Meriwether Lewis, and William Clark are rich with details of the inspiring and challenging landscape. In the 1830s, an adventurous army captain named Benjamin L. E. Bonneville graphically described his encounter with Hells Canyon: “Nothing we had ever gazed upon in any other region could for a moment capture the wild majesty and impressive sternness with the series of scenes which here at every turn astonish our senses and filled us with awe and delight.”1 Coastal, Columbia Plateau, and Great Basin Native Americans, Oregon Trail pioneers, steamship pilots, cannery workers, lumberjacks, stump farmers, and dam builders all shared a common response to the Northwest's natural landscapes: a sense of awe.

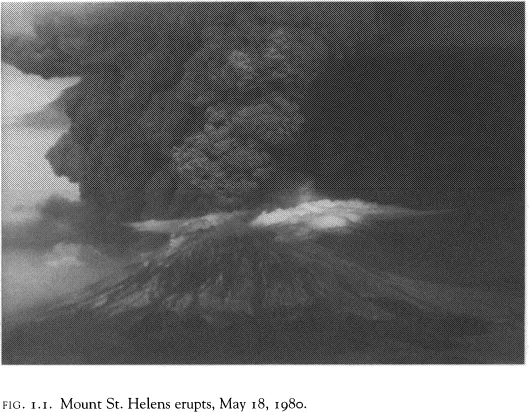

Much of this awe derives from the power involved in the shaping of this dramatic landscape. On May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens reminded us of the natural forces that created the Northwest. On that morning the mountain spewed hundreds of thousands of tons of ash into the air, loosed great debris floods, leveled millions of trees, took 60 human lives, and turned the day to night. Some 6,600 years ago, Mount Mazama—now Crater Lake—did the same thing, only with 50 times the fury. You can find Mazama ash on the East Coast. Indian folklore still recounts the event.

At the end of the Pleistocene—the epoch of the last Ice Age that ended some 12,000 years ago—unimaginable floods surged across what is today northern Idaho and central Washington. These “Missoula Floods”—named for great ice dams and lakes that formed near that present-day Montana town—periodically sent torrents racing into the Columbia River basin when the dams were breached. Coulees, potholes, channeled scablands, and other features of the landscape bear witness to these cataclysmic deluges.

Long before these events, great floods of fiery lava poured forth from fissures in the earth's crust, consuming everything in their paths. Huge portions of central Washington, northeastern Oregon, and southern Idaho were buried beneath hundreds of feet of molten rock. The flood basalts, cinder cones, and lava tubes of the Columbia Plateau and Snake River Plain are solidified testimony to this genesis of some of the Northwest's more striking landscapes.

Even today, we can stand near the floodgates of one of the Columbia or Snake River dams and sense the power of the natural, unharnessed Northwest. Witnessing ocean waves pounding a rocky headland or gale force winds buffeting a Cascade peak evokes a similar appreciation. Northwesterners are imbued with this sense of awe toward the natural environment.

Awe is not necessarily reverence, however. Euro-American immigrants quickly busied themselves with altering the landscapes of the Northwest to fit their needs, desires, and visions of what the land should look like and what it should provide. Reservoirs, farmland, neatly platted towns, channelized rivers, and straight-line transportation routes were far more useful than the rough, “unfinished,” natural Northwest. As we near the end of the second century of this transformation, contemporary residents wonder what happened to the Northwest of expansive forests, free-flowing rivers, uncountable salmon, and wide open spaces; they question whether the transformation has been an unmitigated success—whether what we have gained has always been worth the costs.

Much of this temporal, perceptual journey reflects the continued evolution of our relationship to the natural environment. Initially, the relationship was one of fear because most of the environment was “wild” and unknown. It was the haunt of beasts and bandits, the frightening land between civilizations, and the subject of terror in fairy tales. Later, the environment became a challenge, a place to be overcome and organized, site of a competition between nature and humans that we must not lose. These changes in our perceptions resulted in our treating nature as a commodity with a price, something that could be bought or sold. Natural landscapes became board feet of timber, tons of coal, kilowatts of power, head of cattle, acre feet of irrigation, pounds of pelts, and bars of gold. The value of this natural bounty was determined only by the labor needed to transform it into commodities; in its natural state, it was thought to be valueless.

Recently, a new “value” is being assigned to the Northwest's natural places. This new approach views worth as intrinsic, incalculable in dollar amounts. Not everyone, however, believes that unspoiled views, free-flowing rivers, and abundant wildernesses are valuable for their own sake. The usual course of action is piecemeal protection: listing endangered species, imposing pollution controls, or establishing parks and monuments. These actions are tangible, unlike the altruistic or metaphysical reasons for protection. It is the job of environmental geographers and historians to document and illuminate this journey of changing environmental relations. Numerous contributions to this collection endeavor to do that.

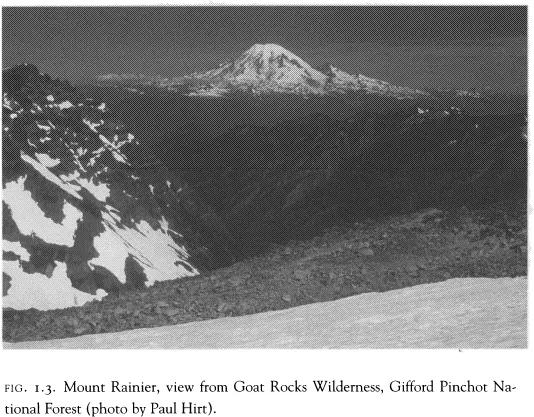

Today, the natural environment is still very much a part of contemporary Pacific Northwest life; it is in part how northwesterners define themselves. Several essays in this collection address how northwesterners develop a “sense of place.” Indeed, much of their lifestyle centers on direct and indirect linkages to the natural environment—even in the region's largest cities. A friend in Seattle said of Mount Rainier, “It's my reference point, my compass bearing. Even on a cloudy day, I know it's there.” Portlanders feel the same way about Mount Hood. Others locate themselves by the Columbia and Snake Rivers, Lake Coeur d'Alene, or the Sawtooth and Bitterroot Mountains. Even locked in traffic in one of the Northwest's large cities, residents can look just beyond the car windows to forested mountains, meandering rivers, undulating prairies, or smooth, gray saltwater bays.

In the Northwest, people's icons and contentious issues are typically environmental as well. Natural landscapes are often at the core of their political, economic, and social debates. Salmon, spotted owls, old-growth forests, wilderness, public land, Columbia and Snake River dams, and air and water pollution dominate the discussion; limiting growth, establishing greenbelts, enacting bottle bills, and channeling development are common issues.

This regional environmental connection is less ubiquitously strong elsewhere in the nation. Residents of the Midwest don't get as excited over the fate of their prairies, nor do south Atlantic Coast denizens over the condition of their Piedmont. Residents of other parts of the country do perceive the Northwest in these terms, however. The Northwest is less well known for memorable cities or notable cultural contributions than for national parks, outdoor recreation, fish, tall trees, and volcanic peaks—and perhaps coffee. These are the attributes northwesterners represent and relate to. They are the Northwest, even for Washington, Oregon, and Idaho's most recent residents.

Even as the traditional extractive industries of timber, mining, fishing, and ranching lose economic dominance, people's connection to the environment remains strong. Newcomers surveyed for the reasons they chose to move to the Northwest always rate the natural environment near the top; they even select this at the expense of a well-paying job. The newer “high technology” businesses—Sony in Eugene, Intel in Portland, Microsoft in Seattle, and Micron in Boise—report that quality-of-life reasons attracted them to the region. It is no accident that outdoor gear purveyors such as REI and Eddie Bauer chose to headquarter in Seattle. Most northwesterners would rather visit the mountains than a museum and would choose the ocean over an opera.

NATURAL DIVERSITY

Fundamental to understanding the role of the environment in the Pacific Northwest is a firm grounding in the region's physical geography. The Northwest's landscapes are exceptionally diverse. It is important to realize that this diversity exists by all measures. There are striking differences in precipitation, temperature, landforms, vegetation, rock types, and soils. Of these, the most important controlling factors are climate and topography. Together these two influence the remainder of the environmental attributes as well as much of the human experience in the Northwest. The remarkable contrast between eastern and western Oregon and Washington or between northern and southern Idaho is traceable primarily to the shape of the land and the long-term influence of weather. Native American and recent northwestern economic activities, settlement patterns, and transportation routes also reflect these natural controls.

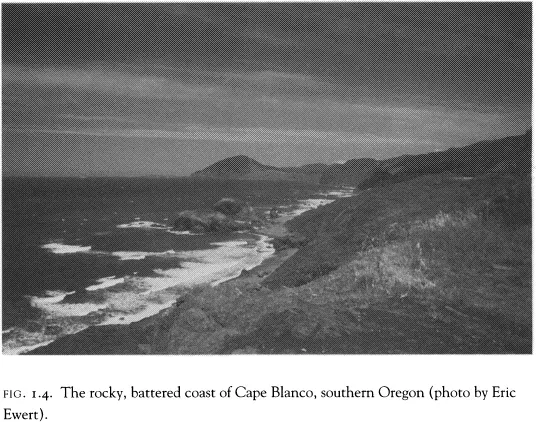

Imagine running your hand over a raised-relief model of the Northwest from west to east. Your fingertips sense a wide variety of surfaces and sensations. After leaving the cold waters of the Pacific Ocean, your fingers quickly gain elevation as you climb the Coast Range. Unlike the south Atlantic coast—where the rolling Piedmont borders an expansive coastal plain—the Northwest leaps from the sea. In many places, the Coast Range mountains rise directly from the ocean, shouldering up in a jagged and abrupt edge of headlands, embayments, sea stacks, and islands. What beaches do exist tend to be narrow and subjected to intense wave activity that may coat them with gravel or cobbles instead of the sand of the East and Gulf coasts. This relationship between sea and mountains precluded the development of large cities on either Oregon's or Washington's coasts. Although Indian and Euro-American fishing villages and towns were and still are quite common, they have never grown to great size.

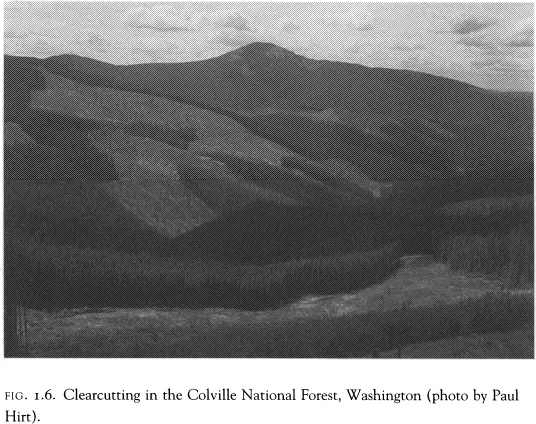

The journey up the Coast Range feels carpetlike as your fingers rub over a thick cloak of evergreen trees: fir, spruce, cedar, and hemlock. The sensation, however, is like that of a three-dimensional checkerboard, because many clear-cut logging swaths now riddle these forests. Some are old-growth forests, with trees that are 1,000 years old and home to the threatened spotted owl. In the far northwestern portion of Washington, the Olympic Mountains greet your hand with 8,000-foot summits, a temperate rainforest with an annual rainfall of well over 100 inches, and many small glaciers. In southwestern Oregon, the Coast Range gives way to the irregularly folded and faulted Klamath-Siskiyou mountain system, which spills into northern California.

After reaching only three to four thousand feet in most of the Coast Range, your fingers drop back down into an extensive inland valley. Stretching from Eugene in the south to Bellingham in the north, the Willamette Valley-Puget Sound lowland is the site of verdant agriculture and sprawling settlement. It is also the most densely populated part of the Pacific Northwest. These lowlands house the largest cities, the most abundant transportation routes, two state capitols, and the greatest concentration of industry. Here the rainfall is high enough, the seasons mild enough, and the soils deep enough for extensive cultivation. The rich farmland, especially along the Willamette River, attracted most of the region's first immigrants and was instrumental in Oregon's achieving statehood in 1859, a full 30 years before Washington and Idaho. Much of this river valley would be a mixed deciduous and evergreen forest if not for the intensive cultivation and historic Native American practice of clearing with fire.

The stunning juxtaposition of mountain and water, forest and farm, so famed in the Northwest, is most dramatic around the Pacific Northwest's inland sea, Puget Sound. Confined by the Olympic Mountains to the west and the Cascade Mountains to the east, great lobes of glacial ice rasped their way south through this lowland. The glaciers gouged channels hundreds of feet below sea level and piled the debris as islands and broad alluvial plains. Dense settlement from Olympia in the south to Vancouver, British Columbia, in the north has long focused on the splendid ports, deep-water channels, and fertile farmland the glaciers left as they retreated. One of the finest inland waterways in the world, Puget Sound is connected to the open Pacific by the Straight of Juan de Fuca, which passes between the Olympics and Vancouver Island.

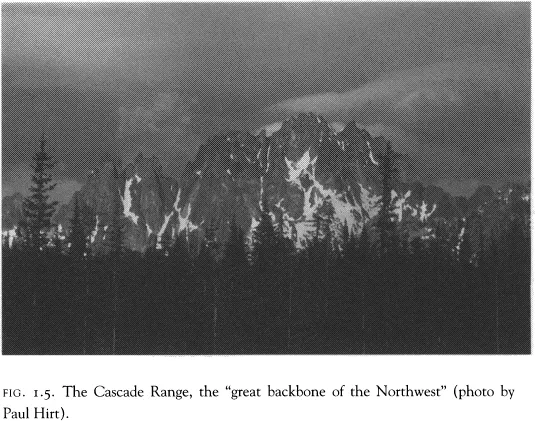

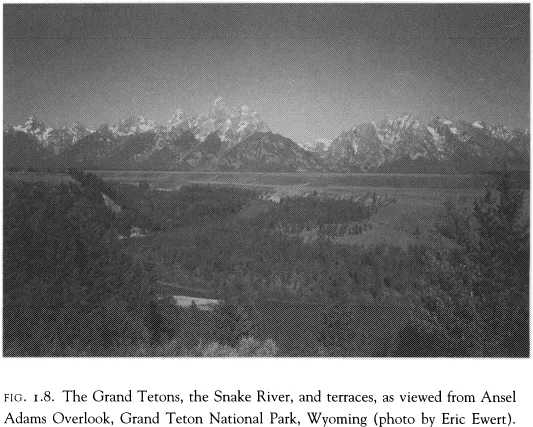

Soon after leaving the valley and sound, your fingers climb rapidly again, up the slopes of the Cascade Mountains. This, the great backbone of the Northwest, stretches from California into British Columbia. It is broken only in two places along its entire length: by the Columbia River along the Washington-Oregon border and by the Klamath River in southern Oregon and northern California. Here, too, great forests cover the hills, nurtured by abundant precipitation. Clear-cutting is common again and displays an odd geometry when one flies into Portland or Seattle. As you explore the range north to south, isolated peaks catch your fingertips. These are the great volcanic summits of the Cascades, the highest of which, Mount Rainier, looms 14,000 feet above Seattle. Its lofty slopes hold more than 25 active glaciers fed by remarkable snow accumulations, sometimes in excess of 100 feet in a single winter. Mount Hood similarly dominates the skyline above Portland. All of the Cascade peaks are dormant volcanoes. Despite Mount St. Helens' warning, northwesterners tend to treat them as extinct mammoths and erect ski resorts, vacation cottages, and recreation facilities on their precipitous slopes. People cluster in valleys in the mountains' shadows and along rivers that race down their margins.

As your exploration continues, the steep journey down the east side of the Cascades begins the most unexpected transition in northwestern geography: the change from the moist west-side forests to the arid east-side grasslands and sagebrush steppe. Swept along by the dominant westerly winds, water-laden air masses from the Pacific Ocean climb the Coast Range and the Cascades and drop most of their moisture as the lower air pressure and cooler surroundings chill the air below its dew point, causing condensation and the formation of great clouds. As the cooling continues, the clouds deliver copious quantities of precipitation to western Oregon and Washington. On the east side of the Cascade summits, the process is reversed. The air descends in elevation and warms in temperature, and the clouds disappear. This is the rain-shadow effect, which influences two-thirds of the Northwest.

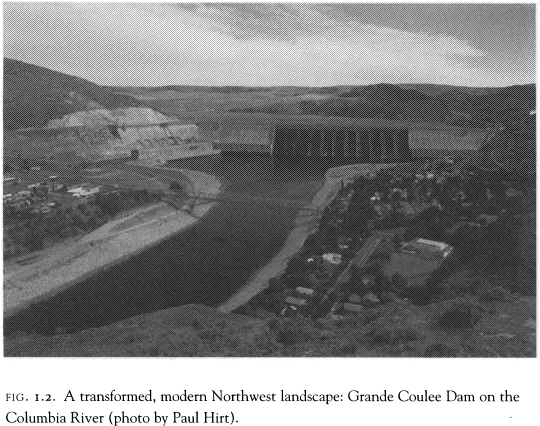

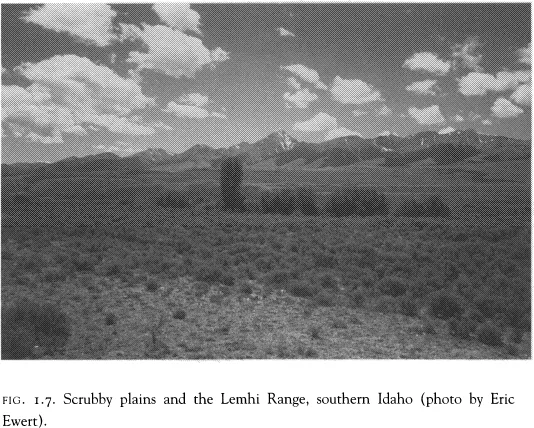

The aridity catches the uninitiated visitor by surprise. The scrubby plains, barren plateaus, and rocky ridges of southern Idaho and eastern Washington and Oregon exist in sharp contrast to the typical northwestern stereotype of Douglas firs and abundant streams. As they gaze at the sagebrush and bare rock, visitors to the Columbia River and Grand Coulee Dam in central Washington often wonder, “Where is all of this water coming from?” The answer lies in distant mountains that squeeze more moisture from the eastward-traveling air masses. These mountains—as far away as Wyoming, Montana, and southeastern British Columbia—catch more rain and snow and give birth to the Columbia River and its major tributary, the Snake River. These green mountains are remote from the stark desert on either side of the river at Grand Coulee, which in places receives a scant seven inches of annual precipitation.

The Columbia River is the great artery and lifeline of the Pacific Northwest. Along its circuitous course, Native Americans settled, explorers journeyed, and pioneers immigrated. Today, the most important east-west highways, railroads, utility corridors, pipelines, and communication facilities parallel at least part of its path. The river has al...