eBook - ePub

A Symbol of Wilderness

Echo Park and the American Conservation Movement

Mark W. T. Harvey

This is a test

Share book

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Symbol of Wilderness

Echo Park and the American Conservation Movement

Mark W. T. Harvey

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

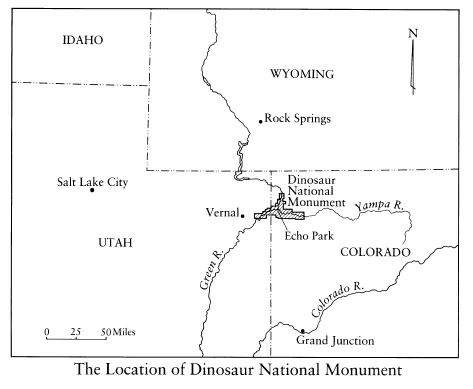

Harvey details the first major clash between conservationists and developers after World War II, the successful fight to prevent the building of Echo Park Dam. The dam on the Green River was intended to create a recreational lake in northwest Colorado and generate hydroelectric power, but would have flooded picturesque Echo Park Valley and threatened Dinosaur National Monument, straddling the Utah-Colorado border near Wyoming.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is A Symbol of Wilderness an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access A Symbol of Wilderness by Mark W. T. Harvey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Forestry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

The Peculiar Past of a National Monument

Olaus Murie, executive director of the Wilderness Society, had become frustrated one January day in 1954, and he decided that Wyoming's Senator Frank Barrett should be the first to know. Barrett was scheduled to appear later that month before a House subcommittee to testify on behalf of the Colorado River Storage Project, and to urge approval of its most controversial feature, the dam slated for construction near Echo Park in Dinosaur National Monument. Murie had been reading the Utah newspapers, whose editorial pages reflected that state's overwhelming support for the project. To Murie's way of thinking, the Salt Lake Tribune and Deseret News deliberately confused the issue with headlines and editorials proclaiming that Echo Park Dam would not flood any dinosaur bones. Murie wanted Barrett to know that for conservationists the fossils were not—and had never been—the point of contention.

Ever since the beginning of the controversy, defenders of the monument had tried to make clear that the dam would not harm the precious fossils—that this was impossible since the quarry of dinosaur remains rested many miles from the dam site. But the prospect of the dam inundating miles of the Green and Yampa rivers and scenic canyons did very much alarm many of the nation's conservationists, who considered this an unwarranted intrusion into Dinosaur Monument and a threat to the national park system. Any mention of flooded bones merely detracted from this more fundamental issue, and was, as Murie told Senator Barrett, “merely a straw man put up for effect.”1

About a year later, as the Echo Park controversy crested in the spring of 1955, Murie found himself scolding the other Wyoming senator out of a similar frustration. Democrat Joseph O'Mahoney had argued the case for Echo Park Dam in the Senate, in the middle of April, taking pains to point out that no one should fear the flooding of fossils. “We know that dinosaur remains are not endangered and that is not one of our arguments,” Murie wrote in exasperation. “To continually dig up this dinosaur bone argument is not a fair procedure, on the floor of the Senate of all places.”2

Wyoming's two senators and most residents of Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico had an obvious interest in raising the issue of the bones. Doing so helped to calm public fears about the dam ruining this part of the national park system, which spanned the border of Utah and Colorado. After all, the very name of the preserve suggested that precious beds of fossils might be at stake, and if they were not, then those who denounced the proposed dam and warned of a desecrated preserve were simply misinformed. And if that were true, it merely confirmed what most residents of Wyoming and surrounding states who stood to benefit from the dam had thought all along: that opponents of the project were driven more by sentiment than by logic. Indeed, the notion that conservationists had bigger hearts than minds was one shared by many Americans in the 1950s. Early in 1954, Time magazine referred to opponents of Echo Park Dam as “professional nature lovers.”3

That comment alone suggests the difficulty of challenging a water project in the era of economic expansion in the United States following the Second World War. Indeed, as this book endeavors to show, the battle to keep the Bureau of Reclamation from having its dam in Dinosaur was enormously difficult for conservation and wilderness groups to win, and most leaders of those organizations did not know if they had the power to do so. Certainly, they lacked the legal means of challenging the project, means that environmentalists of a later generation came to rely on as a matter of course. The 1950s was a vastly different time in the nation's environmental affairs. Even the word environment had not entered the lexicon. More to the point, the Echo Park controversy came along a decade before the Wilderness Act, and nearly two decades before the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. As a result, opponents of the dam did not have the legal means at their disposal to delay or to block its approval. No environmental-impact statement could be requested from the Bureau of Reclamation, no lawsuit could be brought. The controversy—it should be made clear at the outset—played out in an almot purely political arena, and the political odds appeared in many ways to favor the Bureau of Reclamation rather than the National Parks Association, the Sierra Club, or the Wilderness Society.

So the challenge facing Olaus Murie and the gamut of conservationists who sought to defend Dinosaur Monument seemed great. Faced with an expanding national economy, steady population growth in the American West, and a powerful development agency in the Bureau of Reclamation, conservationists could only hope to persuade the public and their political representatives in Congress to reject this plan for a dam in a part of the national park system. Still, as Murie's frustration with Senators Barrett and O'Mahoney suggests, this was no easy prospect. Dinosaur was a remote and virtually unknown national monument, with a somewhat misleading name. What was there other than a desolate and barren landscape with a few remnants of ancient beasts? Would the dam flood the dinosaur quarry? Would the reservoir cover up age-old skeletons that modern science required for study? If not, then what was the whole fight about? What would be flooded anyway, and why was this important? Why should Americans care about it?4

For five and a half years, members of the Wilderness Society, the Sierra Club, the National Parks Association, the Izaak Walton League, and dozens of other organizations struggled to make clear the answer to these questions. They contended that safeguarding the monument from the dam was necessary in order to reaffirm the principles on which the national park system had been founded, as well as to foster protection of a broad range of wilderness lands in the United States. As the controversy unfolded, Echo Park became a prime symbol of the American wilderness, at once magnificently beautiful as well as in danger of disappearing under development pressures.

But Dinosaur National Monument did not become a symbol of wilderness without substantial effort. The monument was hardly well known, even among Americans who traveled regularly to the national parks—as increasing numbers began to do after the war. Here was a part of the national park system known to few Americans, located in an isolated corner of Colorado and Utah. The Green and Yampa rivers and surrounding canyons possessed scenery that many came to consider undeniably grand, but Dinosaur did not have the name recognition of more popular destinations such as Yellowstone, Yosemite, or Grand Canyon national parks. More importantly, as the confusion over the fossil bones reveals, the monument did not possess a clear identity like these other well-known areas in the national park system, and the lack of a distinct identity can be traced to the very beginnings of the preserve. In fact, it was the lack of identity that first gave rise to the suggestion of a dam at Echo Park (and another at Split Mountain). If Dinosaur had been one of the better-known parks, such as Yellowstone or the Grand Canyon, this controversy might not ever have come about. But Dinosaur? What did it matter if a dam were built there? Who cared about a few old fossils?

The problem of having an uncertain purpose and a hazy public identity began in 1915. In that year, President Woodrow Wilson, under authority of the Antiquities Act, proclaimed the new monument around eighty acres of public domain in northeast Utah in order to protect a bed of well-preserved dinosaur skeletons. Wilson's proclamation followed by six years a remarkable scientific discovery—one of the most remarkable in the American West and one of the most memorable in the history of North American paleontology.5

Supplied with funds from Andrew Carnegie, who dreamed of obtaining a dinosaur skeleton for his museum in Pittsburgh, paleontologist Earl Douglass located, one day in the summer of 1909, a fantastic graveyard of dinosaur fossils in the purple, gray, and red hills that made up the Morrison formation north of tiny Jensen, Utah. Over the next fifteen years, Douglass dedicated himself to the Carnegie Quarry, as it came to be known. The quarry contained the remains of some 400 Jurassic dinosaurs, of which nearly twenty skeletons were complete enough to be mounted. Douglass's discovery became renowned as one of the best windows ever opened into the middle period of dinosaur history. Writing to W. J. Holland, director of the Carnegie Museum, Douglass exclaimed that “so far as I know no dinosaur quarry like this has ever been found before…. One couldn't have prayed for anything better and have been at all reasonable in his requests.”6

The fossil quarry sparked great interest in the sparsely populated Uinta Basin of northeast Utah. Residents of nearby Vernal regularly visited Douglass during the excavations, sold him food and supplies, and occasionally pitched in and assisted him. In 1916, one year after Wilson's proclamation, the newly created National Park Service took jurisdiction over Dinosaur National Monument, raising hopes with local residents, businesses, and the Vernal Chamber of Commerce. They hoped that the Park Service would allow some of the fossil bones to remain in place for public viewing, and they urged that a display be erected that would help to attract tourists. Earl Douglass himself expressed interest in such a project; indeed, he became a spokesman for local business interests.

However, when President Wilson established this monument, he was less interested in preserving the fossil bones in their place than in encouraging the Department of the Interior to regulate excavations—a step that Wilson had been persuaded was needed in order to prevent the Carnegie Museum from monopolizing the quarry.7 Then, in subsequent years, despite his intention, the Department of the Interior and the National Park Service continued to permit the Carnegie Museum to remove skeletons, and by 1923 they were nearly gone. By the middle of the 1920s the quarry had been mined of its precious fossils, leaving a national monument with little to show for itself.8 Having been in the spotlight for some years during the excavations, northeast Utah's little communities felt all but forgotten by museums and by the Park Service. Once the skeletons had been carted off to Pittsburgh, Washington, D.C., and Salt Lake City, Dinosaur National Monument seemed to have become a public preserve whose existence could not be justified.9 Local residents were understandably disillusioned, and they had to wait until the early 1950s before the Park Service began to excavate additional fossil bones and place them on display in a new visitor center.

Yet despite deep frustration with the National Park Service, hopes of attracting tourist dollars by no means disappeared, and in the 1930s there began a campaign to protect a large portion of public land north and east of the dinosaur quarry. Here lay a vast, rugged landscape dominated by the Lodore and Yampa canyons and two great tributaries of the Colorado River, the Green and Yampa. A showcase of geologic history, the river canyons provided a haven for wildlife and held innumerable geologic and archeological wonders, including petroglyphs and pictographs decorating the canyon walls. In prehistoric times, these canyons had been home to the Fremont people who inhabited portions of the Colorado Plateau from about 500 A.D. to 1250 A.D. Remnants of their culture were evident in pithouses, petroglyphs, and pieces of pottery and corn.10 In later years, the Ute, who occupied much of presentday Colorado in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, may have hunted and gathered in the canyons.11 During historic times, the canyons did not have permanent inhabitants and seemed to have been primarily a passageway for fur traders and explorers who floated the rivers. Fur trader William Ashley carved his name on a rock wall in 1825, in Red Canyon, north of Lodore Canyon and beyond Browns Park. Ashley descended the Green River and made his way through Echo Park and Split Mountain—as yet unnamed—but left no further sign of his presence.12

John Wesley Powell left a more lasting mark on the region. A geologist by trade, Powell had become enamored with the geology and topography of the West, particularly the Colorado River and Plateau, a region largely unexplored by white Americans in the mid-nineteenth century. With financial assistance from the Illinois Natural History Society and the Chicago Academy of Sciences, Powell launched himself and nine other men in four wooden boats on the Green River in May of 1869.13 Powell successfully descended the Green and Colorado rivers in 1869, and again in 1871. On the first expedition, one of the four boats called No Name wrecked in a furious rapid in upper Lodore Canyon. The three-man crew survived uninjured, but two thousand pounds of provisions and weapons were lost. Appropriately, Powell and his men dubbed the rapid Disaster Falls, and it remains to this day one of the most exciting among many rapids on the Green River in Dinosaur National Monument. Powell named a number of other places inside the present monument, including Lodore, Split Mountain, and Whirlpool canyons, and Island and Rainbow parks.14

On June 18, 1869, Powell rested his crew on a small beach located at the confluence of the Green and Yampa rivers. Here was a perfect site to recuperate. Away from Lodore's rapids, the men relaxed in the grass beneath the cool shade of box elder trees. Surrounding cliffs hovered overhead, and across the Green River from their resting place loomed an eight-hundred-foot sandstone wall, massive and perfectly vertical and so high they had to crane their necks to see the top. The wall dominated the whole scene and, to their astonished delight, sent their voices back across the river in loud echoes. Powell recorded his impression in his daily journal: “Standing opposite the rock, our words are repeated with startling clearness, but in a soft, mellow tone, that transforms them into magical music. Scarcely can you believe it is the echo of your own voice.” Powell decided to call the little glade Echo Park, and the name found its way from his journal to government maps. “Echo Rock” later took the name Steamboat Rock because it resembled a giant ship's prow. Powell and his men treasured their stay in Echo Park, and in 1871 Powell's party camped there for almost a week.15

Following Powell's journey down the rivers, the region surrounding Lodore and Yampa canyons became cattle country, giving rise to small towns such as Maybell, Lay, Hayden, Colorado, and Baggs, Wyoming. A broad, grassy valley known as Browns Park was the center of the industry and a thoroughfare for Butch Cassidy, Tom Horn, Isom Dart and other famous and infamous persons connected to the cattle trade. Two of the so-called outlaw trails between Montana and Texas crossed through Browns Park, skirting the Lodore and Yampa canyons in what later became Dinosaur National Monument.16

Despite the success of the cattle industry, this border region of Colorado and Utah remained isolated from the corridors of transportation and the centers of population in the nineteenth-century West. Vernal, Utah, the small town in the Uinta Basin closest to the canyons, lay nearly two hundred miles east of Salt Lake City and four hundred miles west of Denver, Colorado. In such a marginal region, hopes ran high for new settlements and for still undiscovered sources of wealth. Such hopes appeared in the attempt to establish a colony of homesteaders near Craig, Colorado, in 1915 and in the frequent outbursts of boosterism from local newspaper editors.17

But no amount of hope could overcome the primary obstacle to prosperity—the lack of reliable transportation to the outside world. After the turn of the century, excitement grew with the prospect of a railroad across northwest Colorado, to be built by Denver businessman David Moffat. Moffat promoted his railroad with great enthusiasm, and he had the capital to allow construction to begin. Unfortunately, Moffat's death in 1911 dashed hopes and soon afterward the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad purchased the Moffat line and built the so-called Dotsero Cutoff, a move that left Craig, Colorado, as the western extent of the railroad. Northwest Colorado remained isolated from a good railroad. Residents of Rangely, Colorado, Vernal, Utah, and other towns near the border remained isolated and set apart from the more prosperous communities of Colorado's western slope and Utah's Wasatch Front.18

Given their economic woes, it is not surprising that local residents considered tourism as a prime source of income, and in the 1920s interest grew in attracting visitors to the Lodore and Yampa canyons. Archeologists, explorers, and a handful of river runners came into the area and helped to spark excitement with their writings. Then, in 1928, one A. G. Birch, an employee of the Denver Post, took a much-publicized river trip down the Yampa, which gave rise to a movement to set aside the river and surrounding canyons as part of the national park system. Birch had an urge to explore and a strong interest in promoting desirable tourist attractions in Colorado. Knowing how much “wealthy sportsmen” enjoyed remote spots, Birch believed that Yampa Canyon offered a vacationer's paradise. For three weeks Denver Post readers followed his journey, tantalized by dramatic headlines: “Post's Expedition Is Nearing Perilous Trip Down Cañon” and “Expedition to Risk Death in Wild Region.”19 Given the Birch party's inexperience, the Post headlines probably did not exaggerate the risks. Birch and his companions were lucky to complete the ...