eBook - ePub

Repairing the American Metropolis

Common Place Revisited

Douglas S. Kelbaugh

This is a test

Share book

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Repairing the American Metropolis

Common Place Revisited

Douglas S. Kelbaugh

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Repairing the American Metropolis is based on Douglas Kelbaugh's Common Place: Toward Neighborhood and Regional Design, first published in 1997. It is more timely and significant than ever, with new text, charts, and images on architecture, sprawl, and New Urbanism, a movement that he helped pioneer. Theory and policies have been revised, refined, updated, and developed as compelling ways to plan and design the built environment. This is an indispensable book for architects, urban designers and planners, landscape architects, architecture and urban planning students and scholars, government officials, developers, environmentalists, and citizens interested in understanding and shaping the American metropolis.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Repairing the American Metropolis an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Repairing the American Metropolis by Douglas S. Kelbaugh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architettura & Design e architettura. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitetturaSubtopic

Design e architettura1 | SUBURBAN SPRAWL |

PAVED WITH GOOD INTENTIONS

“But then the Depression came, and war, and a generation of Americans grew up who had apparently forgotten what a town was, or how a city was built and who were obsessed by enthusiasm for the free passage of the automobile at the expense of all other values. We were told that this was the way it had to be done by hero-architects …; and hero administrators … put it heroically, savagely, into practice, and the Bronx was destroyed, and I-95 and its connectors came to New Haven and smashed through between the railroad station and the old town, destroying everything in their path. And I-95 went on down the east coast, reaming out the centers of cities, scattering neighborhoods, mostly those of black Americans, all the way to Miami, where as its last act it obliterated Overtown, an African American community of long standing, where Cab Calloway had delighted to sing.”

— VINCENT SCULLY, 1999

WE ARE A CULTURE OF PRODUCTION AND CONsumption. We produce and consume so much because we borrow so much. We borrow from the past when we burn fossil fuels and clear-cut ancient forests. We borrow from the present when we overfertilize the land and overfish the oceans. And we borrow from the future when we bequeath government deficits and chemical toxins to our children. Put less gently, we are robbers: by plundering the planet’s savings account and squandering its income, we rob future generations of a good and decent life and maybe of life itself.

The First to Sprawl

No phenomenon embodies and sponsors our predicament more than suburban sprawl does at this point in our history. The United States is the first nation to distribute its metropolitan populations at extremely low densities across the countryside, to achieve that unlikely mix of both sprawl and congestion. The American metropolis is far less dense than its counterparts in Europe, Asia, and other parts of the world—about a third as dense as metropolitan Paris and a thirtieth as dense as metropolitan Hong Kong. And it is getting less dense every year. Only recently have cities begun to sprawl.

Since the first cities of the ancient Near East, cities have existed to define a center. The Egyptian hieroglyph for the city was a cross inscribed in a circle—the idea of a crossroads or center combined with that of a defined border. In Hellenistic and Roman times the very form of the classical city expressed the idea of a center around which a hinterland was organized; later, the Renaissance used the techniques of linear perspective along great boulevards to reinforce the meaning and dominance of the core…. The coming of the global trading city and the 19th-century industrial city did not contradict but reinforced the desire to create classical urban space at least at the city’s core.1

Why are we the first suburban culture in history, with more people residing in the suburbs than in the city or country? An underlying reason for spreading out is the historical propensity of Americans to depend on expansion, growth, and the new start as a way to solve difficult problems. Westward expansion across a vast continent provided a giant safety valve. Abundant natural resources supplied inexpensive building materials. Compared to other cultures, Americans opted for bigness over quality—big houses with big rooms, quickly constructed on big parcels of land. They also opted for newness, perpetually starting over again, rather than sticking it out in the old place and reworking it until they got it right. Waste, largeness, obsolescence, and impermanence were not worrisome. There was plenty of room and resources; and no reason to crowd together in small dwellings in tightly packed communities.

Our agrarian roots and pioneer spirit held the promise of generous acreage and commodious homes. There were no compelling reasons for permanence, frugality, or sustainable practices. In fact, there were social and political pressures to be free of these restraints and shed the crowded and oppressive European or Asian models of dwelling and community from which many of our forebears emigrated or escaped.

Another factor in the American way of life is physical mobility. The typical household now moves more frequently than it votes for president or watches the summer Olympics. This transience has deterred the investment in housing of more permanent construction, which is less expensive in the long run than shorter-lived buildings. The easy ownership of automobiles and the vast highway and interstate system amplifies this mobility. Both have made it more convenient and attractive to move to and commute to pastures that are presumably greener. Moving is not the physical ordeal today that it once was when, for instance, the farmhands migrated westward in the 1930s, so vividly depicted in The Grapes of Wrath. Whether for executives being shuffled around by national corporations or for migrant workers, modern vehicles and highways have made migration much easier—with inevitable dissipation in the sense of community.

Automobiles and automobility are by now deeply rooted in American culture. There is now one motor vehicle for every licensed driver, nearly twice as many per capita as a generation ago. Cars and trucks are a major part of our modern folklore, mythology, movies (American Graffiti, Hud, Batman, Road Warrior), art world (Cadillac Ranch), music (The Beach Boys, Don McLean), sports world (Indy, stockcar, and drag racing), entertainment world (demolition derby, monster trucks), styling world (car shows), and media (TV and magazine advertising, Click and Clack). They are also fundamental to our economy, providing many jobs in designing, manufacturing, repairing, servicing, and fueling cars—not to mention the need for roads and bridges, police, insurance, etc. Automobiles are objects of desire as well as of mobility and represent some of the more beautiful and refined industrial designs of the century. Their bodies, grilles, headlights, and tailfins titillate us everywhere we go.

Automobile names “are the single largest set of discriminated nouns in English…. The typical 26–year-old American man can name 12 to 20 colors, maybe 15 fruits, but he can name 60 or 70 cars and tell you something about most of them.”2 Americans also put a lot of money where their mouths are. Young people spend four billion dollars a year customizing their cars, not to mention what they spend to buy them in the first place. We are not going to exorcise automobiles from our culture in the foreseeable future. Nor do we have to. We can, however, tame these metallic monsters and return them to an expeditious and pleasurable mode of travel, rather than the addictive answer to our restlessness.

Our national restlessness seems to go hand in hand with the local traffic we have come to expect daily on our crowded roads. Gone is the sheer joy of driving—the exhilaration of acceleration and the wind-in-the-hair, heart-in-the-mouth thrill of moving effortlessly and fast along an open highway. Life on the run has become the norm, and the transportation network is overloaded. Gridlock is no longer just a rush-hour phenomenon. It occurs much of the time in much of the metropolis here and abroad. “In the 1950s a similar situation faced two other cities, Tokyo and Seoul. Tokyo opted for a mass transportation system that today is respected the world over. Seoul went for more roads; today the city has twenty-eight lane highways and traffic jams that would impress even a Manhattan taxi driver.”3

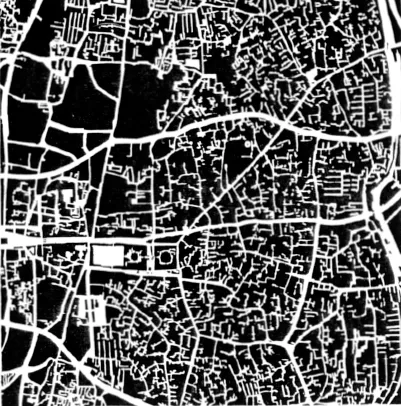

What a difference the car makes in urbanism. The top diagram is of public streets in Ahmedabad, an Indian city founded in the fifteenth century; at the bottom is Irvine, California, established in mid-twentieth century. The former is pre-automobile; the latter is planned for the automobile and is, remarkably, drawn at the same scale. (Allan Jacobs, Great Streets, MIT Press))

The biggest perpetuator of sprawl is zoning that segregates different land uses into large, single-use zones that are monocultures, i.e., all garden apartments, all single-family houses, all retail, all office. Large arterials separate these areas like rivers, impassable to pedestrians and often gridlocked for automobiles.

Not long ago the Southern California Association of Governments, including some thirty municipalities around Los Angeles, commissioned a computer simulation of traffic in the year 2010. It modeled many possibilities, among them double-decking highways, additional lanes, expanded bus and rail transit service, and staggered work hours. They concluded that nothing that could be done to add capacity to the system would have a lasting effect on congestion—except for one strategy that was not a transportation fix per se. Mixed-use neighborhoods, because they eliminate the need for trips in the first place, were found to offer a permanent solution to traffic congestion!

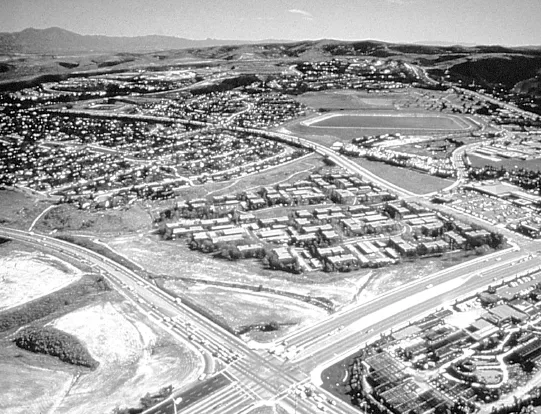

American metropolises have managed to do the impossible: to sprawl at very low densities and choke themselves with traffic congestion at the same time. If we are going to make metropolitan areas that are more livable, more affordable, and more sustainable, we need new paradigms and mixed-use models that do not perpetuate sprawl and that recognize its economic, social, and environmental costs. Peter Calthorpe and Henry Richmond have succinctly summed up the situation:

Unrestrained sprawl around our cities is generating profound environmental stress, intractable traffic congestion, a dearth of affordable housing, loss of irreplaceable open space, disinvestment in our inner cities, and life-styles which burden working families and isolate elderly and singles. We are using land planning strategies that are 40 years old and no longer relevant or affordable to today’s culture. We are still building World War II suburbs as if families were large and had only one breadwinner, as if jobs were all downtown, as if land and energy were endless and as if another lane on the freeway would end traffic congestion. It is time to overhaul the American dream, returning to the values and patterns of our traditional towns—diversity, community, frugality, and human scale. We must move back from cul de sac subdivisions to elm street neighborhoods, from drive-through commercial strips to main street communities, quite simply from segregated sprawl to places more like traditional American towns.4

A Primer on Costs

Some thoughts on the nature and definition of costs may be helpful before tallying the costs of sprawl. There are two important distinctions to be made for the purposes of this book. First, there is the distinction between public costs and private costs. Public costs, a.k.a. social costs, are the ones borne by all of society, or at least by a large group or class within it. These costs are exacted primarily through government taxation or through collective sacrifice or loss. Private costs are the ones paid in the market by individuals for goods and services.

There is also the distinction between cost and price. Price is the numerical value affixed to goods and services by the market. It is driven by supply and demand, although often modified by taxes or subsidies. Cost, sometimes referred to as true cost, is the fully reckoned cost of providing goods or services. It includes both direct and indirect costs. Direct costs include expenditures by the supplier for items such as design, supplies, raw material, manufacturing, packaging, transportation, advertising, sales, transaction fees, and profit. Indirect costs include environmental and social costs or subsidies that are not reflected in the price. They are often called externalities, a term that also can refer to either costs or benefits that accrue to a third party. External costs refer to measurable costs, such as environmental clean-up or disposal costs, and to less quantifiable costs or losses, such as degradation of the quality of life; loss of comfort, convenience, or time through congestion, crime, or negligence; or outright loss of life. These externalities are borne by individuals or society or both.

However brilliant and quick the market may be at establishing price for a given product or service, it is not very good at determining cost including externalities. In a more perfect market, the true and total cost would be more accurately reflected in the price. A closer correlation between cost and price would serve to assign the costs for goods and services to the actual beneficiaries of those goods and services. Although there may be cases or times when society decides it is advantageous to favor or penalize a particular enterprise, sector of the market, or segment of the population, a society has a greater chance of equity and sustainability when market prices square with true costs. Without such accountability, society or an economic unit within it can make foolish decisions and transactions. This is one of the main reasons that the former eastern block of Socialist European countries, whose centrally planned and managed economies failed to factor in industrial pollution, ruined vast reaches of their environment. Even if the pricing for small items is below cost, it can result in minor environmental deficits that can accumulate into disastrous results. The everyday use of millions of underpriced aerosol cans, for example, has quickly helped to open a bald spot in the planet’s ozone layer. Underpricing can result in false savings and deep risks.

Last, there are subsidies. These are attempts, usually by the public sector but also by the private sector (in the form of charitable contributions), to benefit a particular industry, institution, region, or segment of the population. This assistance can be through grants, services, or tax relief. Sometimes they are out in the open and well known (e.g., the National Endowments for the Arts and the Humanities or agricultural price supports), and sometimes they are hidden and hard to trace (e.g., the oil depletion allowance; defense contracts that aid corporate research and development; military commitments that benefit a particular foreign investment; reduced tuition at state universities). Government subsidies are often hidden because special interest groups have successfully lobbied for favorable policies, taxes, or tariffs that are too subtle, complex, or numerous for the average citizen to follow. Private gifts and grants are often publicly acknowledged, but they, too, are sometimes anonymous or secret for the sake of the donor and/or the recipient. Because subsidies, including many to suburbia, are often hard to understand and track, it is important that we account for them publicly.

The Economic Costs of Sprawl

Government subsidies have played a large role in promoting low-density suburban development. The federal income tax deduction for home-mortgage interest payments has had a powerful impact on home ownership, raising it to among the world’s highest rates—65 percent, almost double the turn-of-the-century rate. However, this tax policy has tended to encourage the construction of detached single-family houses, most often in suburbs. This single tax provision costs the federal treasury an estimated $50 to $90 billion a year, making it in effect the broadest and most expensive welfare program in the U.S.A. Earlier this century, the federal government intervened after the Great Depression to bail out the banks that were financing suburban homes. Later, FHA loan guarantees and VA loans made long-term and low-interest mortgages available to homebuyers (not for renovation of existing homes), who were purchasing new homes for the most part in suburbia.

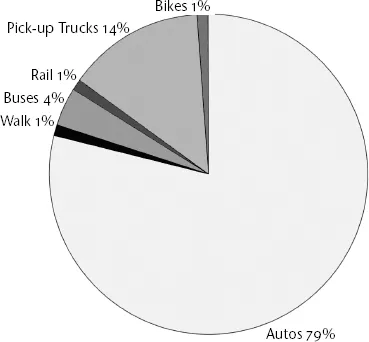

“The price of private vehicle travel in the United States is very low. Private vehicle users do not pay directly for the pollution they generate or the congestion they impose on other travelers. Police and other emergency services, maintenance of local roads, and many other parts of the transportation system are supported indirectly by property and other taxes. Gasoline taxes, vehicle-registration fees, driver’s license fees, and automobile taxes are lower here than anywhere in the developed world. Parking is offered free to most workers and shoppers. Given the extent of subsidies to private vehicle use, we should not be surprised that other forms of transportation cannot compete….” (Genevieve Giuliano, “The Weakening of the Land Use/Transportation Connection,” On the Ground, summer, 1995, pp. 13–14; pie chart, p. 4.)

Another oft-cited subsidy is the federal road-building program, which promoted automobile usage almost to the exclusion of rail transit. The ...