![]()

1. Woodstock and the First Watershed

We have a tradition in our family that sometime in the past century, one of our ancestors crept out of the ground in Lebanon, Connecticut, and as soon as he got money enough together to run away with, came up to Queechy Vermont, where we have remained ever since.

Marsh, speech at Forefathers' Day, Middlebury, Vt., 18591

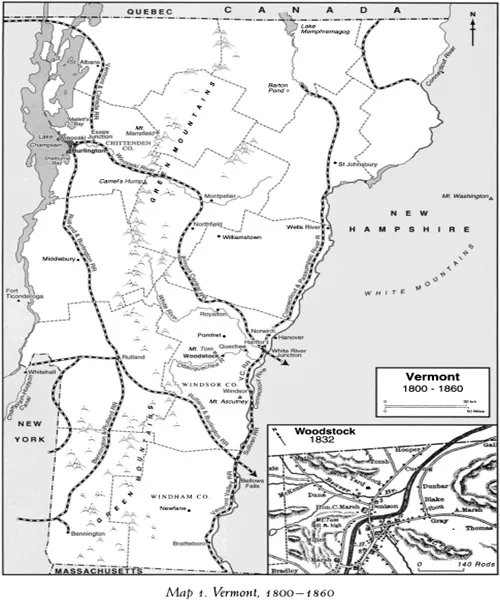

GEORGE PERKINS MARSH WAS BORN IN WOODSTOCK, Vermont, “the true date of my happy nativity being the Ides of March 1801.” So he told a friend who had wrongly antiquated him back into the eighteenth century.2 It was a bitter winter, this first of the new century. Typhus raged in Woodstock village along the terraced flats of the Ottauquechee River, usually known as the Quechee. Across the river, the family of Charles Marsh, Esquire, Woodstock's leading lawyer and U.S. District Attorney for Vermont, escaped the lice-borne malady. Six years later the family left their riverside cottage for a brick mansion a hundred yards north at the foot of Mount Tom.

Here, overlooking the village opposite, Charles Marsh brought up a large family, entertained visiting dignitaries, and managed his farm, the choicest in the township. He owned much of Mount Tom, and his well-tilled fields and meadows covered the whole of the rich intervale in the great bend of the Quechee north of Woodstock. The new road from Royalton, a turnpike in which Marsh held a half interest, skirted his house and entered Woodstock on the Quechee bridge Marsh had built in 1797. Across this bridge to Elm Street, which he had likewise laid out, Charles Marsh would walk to his law office.

From the summit of Mount Tom, treeless since a devastating October fire in George's very early childhood, the boy could survey his entire cosmos. The windswept summit afforded an unobstructed view of the village five hundred feet below. To the west, the main range of the Green Mountains was dark with spruce, hemlock, and white pine. Seven miles to the east lay Hartford, the home of George's grandfather, Colonel Joseph Marsh. A few miles farther downstream, the Quechee entered the broad Connecticut River, spanned seven miles upstream by a bridge linking Norwich, Vermont, where young Marsh would briefly teach school, and Hanover, New Hampshire, the site of his alma mater, Dartmouth College.

This was no static panorama but one in ceaseless flux, rapidly being transformed by the forces George Marsh would so memorably limn in Man and Nature. Thirty years of clearing and planting had converted the wooded lower hills surrounding Woodstock into field and pasture. On higher, steeper slopes the forest was also receding, as demands for fuel and the effects of pioneer profligacy took their toll. The runoff of rain and snow on denuded hillsides sped erosion and depleted once abundant supplies of fish and game. Frequent floods washed out bridges and mill sites.

From his first years, Marsh was acutely aware of such metamorphoses. “Too sterile ungrateful and cold to furnish food and shelter even to the frugal and hardy Indian,” the Green Mountains had remained for the most part “an untenanted and untenantable wilderness,” he wrote half a century later.3 “Born on the edge of an interminable forest,” as he termed it, he himself saw much of it cut down for timber, fuel, and the making of fuller's soap from potash, then in huge demand for manufacturing woolen cloth, especially in England. In Woodstock “every family made its own soap, preparing also its own lye,” Marsh recalled, from “the numerous potash factories supplied with material from the ‘clearings’ then going on.”4

Such clearings had an impact on the fish in local streams. Sent to school in 1811 at Royalton, fifteen miles north, the ten-year-old fisherman found the White River “a very different ichthyological province from that of Woodstock.” Lower-lying than the Quechee, the White River valley had been earlier and more thoroughly deforested. There Marsh caught eels and gathered freshwater clams “never found in forest streams but only [in] those cleared and cultivated.”5

Birds were also affected. Commenting on their nocturnal migrations along natural channels now become thickly settled, Marsh in Man and Nature recalled a boyhood village

at the junction of two valleys, each drained by a mill stream, where the flocks of wild geese which formerly passed, every spring and autumn, were very frequently lost, as it was popularly phrased, and I have often heard their screams in the night as they flew wildly about in perplexity as to the proper course. Perhaps the village lights embarrassed them, or perhaps the constant changes in the face of the country, from the clearings then going on, introduced into the landscape features not according with the ideal map handed down in the anserine family, and thus deranged its traditional geography.6

Many such changes, Marsh later stressed, were at least for some time irreversible. The fierce fire that had denuded Mount Tom in his childhood consumed humus as well as trees: “the rains of the following autumn carried off much of the remaining soil, and the mountain-side was nearly bare of wood for two or three years afterward.” Although Mount Tom was soon again thickly wooded, “the depth of mould and earth is too small to allow the trees to reach maturity.” No trees over six inches in diameter survived, and seedlings would go on dying “until the decay of leaves and wood on the surface, and the decomposition” of rock beneath, had “formed, perhaps hundreds of years hence, a stratum of soil thick enough to support a full-grown forest.”7

In fact, Mount Tom was replanted by Frederick Billings in the 1880s with exotics—Norwegian spruce, European larch, and white ash; thus only fifty years after Marsh's somber augury in Man and Nature, it was well clad in mature growth.8 Yet Marsh's insight that the intensity of human-induced damage might long delay natural recuperation remains valid. And in this instance, as Marsh often came to stress, it was not nature alone but nature aided by human artifice that had restored Mount Tom.

Revolutionary Vermont usually calls to mind Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys, brash, unschooled, ultrademocratic; but the Marshes were emphatically not Vermonters of this type. Indeed, for years they strove not to be Vermonters at all. They sought instead to set up their own Puritan commonwealth between the Green Mountains and the White Mountains, a pious, orderly, Dartmouth-focused New Connecticut. Their political arcadia unrealized, the gentry of eastern Vermont contented themselves with inculcating genteel virtues in their offspring. In frontier Vermont, George Marsh was brought up a sober Calvinist patrician.

For a long time the Green Mountains separated two hostile worlds. To the west, from Bennington and Rutland north through the Champlain Valley, came western Connecticut backwoodsmen. Dissenters from Congregational conformity, some were revivalists, others freethinkers. In orthodox eyes, western Vermont was notorious as the abode of atheists who “chuse to have no Sabbath—no ministers—no religion—no heaven—no hell—no morality.”9

East of the mountains, settlers came from conservative central and coastal Connecticut. Orthodox in religion and Federalist in politics, many were educated and prosperous. The likes of the Marshes along the upper Connecticut and its tributaries were noted for “puritanical gravity, that shrewdness and Connecticut peddler's air, which enables them to drive a lucrative business in the humblest and most unpromising pursuits.” But an 1840s visitor also found them honest and “punctual to a fault.” In eastern Vermont roads were better than those to the west, fences in good repair, houses neat and weatherproof. Yale's president Timothy Dwight smugly judged, in 1803, that “steadiness of character, softness of manners, a disposition to read, respect for the laws and magistrates, are all extensively predominant in this region.”10

Joseph Marsh, George's grandfather, exemplified such traits. With his mother, wife, nine children, and several brothers' and cousins' families, Marsh had moved north from Lebanon, Connecticut, in 1772. Hartford, their Vermont destination, was one of the Connecticut valley townships chartered by New Hampshire Governor Benning Went-worth at the close of the French and Indian Wars a decade before. In those wars Joseph Marsh had ably served. A man of substance, he was already a town proprietor before he came to Hartford, which throve on timber, potash, and wheat.

He rapidly gained further influence. Colonel of militia, convention delegate, Connecticut Valley spokesman, he was chosen lieutenant governor of the newly independent republic of Vermont in 1778. But misgivings about the radical Green Mountain Boys led his “Dartmouth College party,” headed by Dartmouth president Eleazar Wheelock, to seek separate autonomy, or at least Vermont hegemony, for the upper Connecticut Valley. They failed. In 1784 the towns east of the river rejoined coastal New Hampshire, and the Marsh-Wheelock party capitulated to the Aliens. Though they saw the Aliens and their ilk as “friends of Hell,” they were “prepared to make a pact with the devil himself” to protect their properties against New Hampshire and New York. The pact reflected little faith on either side, Ethan Allen terming the Marsh faction “a Petulent, Petefoging, Scribling sort of Gentry, that will keep any Government in hot water till they are Thoroughly brought under by the Exertions of authority.”11

Joseph Marsh again became Vermont's lieutenant governor in 1787-89. Although radical Jeffersonians for the most part controlled the state (admitted to the Union in 1791), conservative Federalists long dominated its eastern counties. As chief justice of the Windsor County Court until 1795, Joseph Marsh was legendary for his capacious memory, logical acuity, and equable temper. Meticulous in dress and manner, he remained until his death in 1811 “a perfect Federalist gentleman … of the pure Washingtonian school,” recalled a grandson, “and trained his children in it.”12 And trained his grandchildren in it too, recalled George Perkins Marsh near the end of his own life.13

Charles, eighth of Joseph Marsh's twelve children, and a graduate of Dartmouth and of Judge Tapping Reeve's famed law school in Litchfield, Connecticut, opened his Woodstock law practice in 1789—the first lawyer there, the third in Windsor County. Charles Marsh is said to have arrived in Woodstock without a shilling in his pocket beyond the price of his first fifty acres;14 but with his undoubted talents and an influential father heading the county court, success and prestige came quickly.

In 1790, Marsh and his wife, Nancy Collins, moved from the Eagle Hotel into the frame cottage at the foot of Mount Tom, known for the next half century as “Mr. Marsh's hill.”15 Here Charles, Jr., was born in 1790, and Nancy Marsh died after giving birth to Ann Collins in 1793. Five years later Charles married Susan Perkins Arnold, also recently widowed, who brought with her a two-year-old daughter, also named Susan. Charles and Susan had five more children: Lyndon Arnold, 1799; George Perkins, 1801;Joseph, 1807; Sarah Burrill, 1809; and—the eldest son having died—another Charles, in 1821.

As a lettered man and trained advocate, Charles Marsh was at first an anomaly. Newly arrived from Connecticut, Charles's cousin Jeremiah Mason found Vermont's courts “badly organized and usually filled with incompetent men. Most of the members of the bar were poorly educated, and some of vulgar manners and indifferent morals.” In Windham County's Newfane, just south of Woodstock, legal credentials scarcely mattered. “I certainly knew very little law,” Mason recalled, “but that was the less necessary as my opponents knew not much more, and the judges I addressed none at all.” Worse yet, “a large portion of the inhabitants were new settlers and poor, and of course not desirable clients.” Mason departed to hang out his shingle in New Hampshire, where he hoped to find lawyers who were gentlemen, judges scholars, and clients well-heeled.16

Charles Marsh was made of sterner stuff—or perhaps he concurred with state supreme court judge Royall Tyler, who termed Vermont “a good place for lawyers” because “all the rogues and runaways congregated” there. Woodstock became the county seat in 1790, Marsh planning the new courthouse. For a decade he monopolized Woodstock's legal business, and for many years led the Windsor County bar. Severity and hot temper made him widely feared; for punching a legal opponent in court, Marsh was scathingly rebuked by his father, sitting as judge. He thereafter behaved with icy restraint, excoriating his foes in a low-pitched voice that compelled close attention. He browbeat juries, too. In one defense Marsh agreed with the prosecutor that his clients were “poor and mean, wicked and criminal”; they ought to be hanged. But, he warned, the jury must heed nothing but the evidence; were they swayed in the slightest by his clients' reputation, “you will as richly deserve the state prison as they deserve the gallows.” Marsh won the case.17

During the War of 1812, when antiwar Federalists briefly controlled Vermont, Charles Marsh was twice elected to public office. Each time he courted public odium. In the Vermont Council of Censors, which met every seven years to revise the state constitution, Marsh urged a Senate elected by men of property to offset the “hasty, inconsiderate, violent rabble” in the Assembly. In the U.S. Congress, Marsh took a grim pride in unpopular stances. Backing a bill to raise congressional pay from six dollars a day—a bill disastrous to several politicians—he had the temerity to demand ten dollars! Like his son George a generation later, Charles Marsh was pilloried for legislative arrogance. Yet he remained staunchly republican; “how indignant my old Federal father was,” George Marsh later recalled, when England at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 “abandoned the peoples of Europe to the tyranny of priests & princes.”18

Charles Marsh gained no public renown. Better schooled and more brilliant than his popular father, he did not make the most of his talents. Echoing Joseph's political and social views, Charles lacked the tact, even the will, to make them palatable to others. He was never eager for office; hauteur ensured he never long retained it.19 Despite habitual self-deprecation—inherited by and intensified in his son George—Charles Marsh saw himself inferior only to God. To most mortals he was clearly superior. Confident of never lying or acting unjustly, he pitilessly pilloried anyone he thought did so. His portrait shows a man one would not care to gainsay: a spare six-footer with a narrow, deeply lined face and thin-lipped, derisive smile.

Reared in a stern religion, Charles Marsh remained a strict Calvinist. He helped found Woodstock's Congregational Society and gave the land for its meeting house. A stalwart of the American Bible, Education, and Colonization societies, Board of Foreign Missions, and Society for the Promotion of Temperance, Marsh never deviated from their aims. Yet he was besieged by doubt as to their efficacy and his own moral worth. It was like him to argue for banning liquor traffic by blaming himself for having “sold spirits to a person who under its influence had abused his family, and consequently been imprisoned.” In grieving the untimely death of his eldest son, Marsh found himself “dumb before my Judge.… ‘How shall I answer Him for one of ten thousand of my transgressions?’”20 Rectitude was the mainstay of Marsh's piety; he taught his children to fear God not as a loving Father but as a righteous Judge.

Charles Marsh was gentler at home than in the courtroom, but a tyrant nonetheless. George's father was as quick to condemn stupidity as to denounce a lapse from probity; a young Marsh ought to know as much as possible about everything. Thoroughness was a lesson George learned early. Watching his father inspect the building of their new house, he “never forgot the stern rebukes administered to the laborers when their work was found to be ignorantly or carelessly done.”21 Slow and negligent learners took a back place in the family circle; George was impelled by more than mere curiosity to absorb the encyclopedia from the age of five. His family viewed him as a paragon because he yearned to know everything from mechanics to needlework; precocity aroused admiration, exemplary conduct exempted him from criticism. At an age when most children are learning the alphabet, George Marsh was well on the way to becoming a pedant.

His rigorous childhood training left lasting traces. Marsh ever reveled in encyclopedic knowledge; versatility was a passion for this polymath in myriad diverse realms. He hungered for data of all sorts. And he forever interjected recondite lore into letters and essays, sometimes to illustrate a point, often simply as self-indulgent fun. Marsh never ceased finding virtue in facts, or delighting in knowing so many of them. In the home of Charles Marsh this had paid well.

George's mother, unlike his father, was brought up in an...