![]()

ALONG MONTANA HIGHWAYS

I spent the rest of a long, fine late-summer afternoon drifting down through Montana, south to Missoula and then over to Helena. I only have to be in Montana—any part—about ten minutes to reconvince myself that it is easily the most beautiful American state . . . On a fine day, with the great thunderheads rafting across the high sky, Montana can hold its own, for sheer visual beauty, with any landscape in the world.

LARRY MCMURTRY, ROADS: DRIVING AMERICA'S GREAT HIGHWAYS

Roads no longer merely lead to places; they are places.

—J. B. JACKSON, ROADS BELONG IN THE LANDSCAPE

BOUNDARIES

1 FORTY-NINTH PARALLEL

“From the point on the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude . . . the line of boundary between the territories of the United States and those of Her Britannic Majesty shall be continued westward . . . to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver's Island” (Treaty Establishing Boundary West of the Rocky Mountains, 1846). With a pen stroke on June 19, 1846, President James K. Polk completed a new political geography across a still-incipient American West. And he preordained a cultural landscape that remains etched across Montana's broad and sweeping roofline.

The Canadian-American boundary marks the world's longest peaceful border, a great symbol of hemispheric fraternity. It also reveals how an enduring geopolitical fact, created more than 150 years ago, has shaped two distinctive human geographies. Political realms established along that dividing line influenced subsequent patterns of settlement, cultural evolution, and distinctive agricultural policies.

Still, connections remain. Most palpably, the cross-border crackle of radio stations, the shared small-town sports events, and the daunting rural economy faced by both Canadian and American farmers are reminders that propinquity helps create a common life. On Montana's northern edge, such juxtapositions especially focus on fourteen ports of entry where twin Canadian and American settlements are anchored around small windswept collections of customhouses and border facilities.

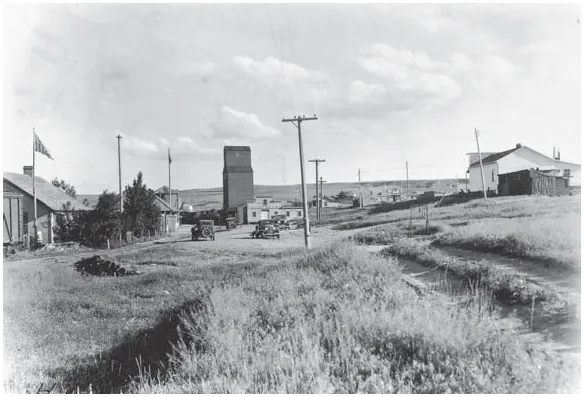

Sweetgrass (Montana) and Coutts (Alberta) have been such cross-border neighbors ever since the two small settlements blossomed during dryland farming booms around 1900.

The two views shown here look south across the border from the Canadian side. The customhouses, originally located next to the rail tracks on the left (east) side of pl. 1a, have migrated to the right (west) and now are aligned along the multilane highway out of sight above the berm on the right side of the modern image (pl. 1b). The grain storage and processing facilities on the American side of the line have expanded greatly since 1932, suggesting the increasing economic linkages that bind the nations more closely together. At the same time, the growth and size of administrative and inspection facilities demonstrate the ever greater political complexities in crossing from one country to another.

Then and now, the photographer stands in a geopolitical no-man'sland barely north of the border. The site is a parking lot for Canadian customs workers. It is not a place for casual wandering: permission must be granted to walk in the boundary zone without raising suspicions, north or south. But overall, congeniality reigns. Here, good borders make good neighbors, as well as Montana's longest, most remarkably linear landscape feature.

2 INTO THE MOUNTAINS

Two hundred years ago, on a warm July afternoon in 1805, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark entered the Rocky Mountains. They had toiled for more than a year up the Missouri River from St. Louis. Their journey had already taken them through a remarkable country in which they saw extraordinary people, plants, and animals. But now, on July 17, 1805, they were poised to leave the Great Plains and enter the mountains just southwest of present-day Great Falls.

Geology prepared the way. Fifty million years earlier, volcanic eruptions had dramatically reshaped the local scene. The Adel Mountains are remnants of that igneous landscape, a ragged collection of sharp, steeply sloped ridges and narrow, rocky dikes through which the Missouri River has carved a path.

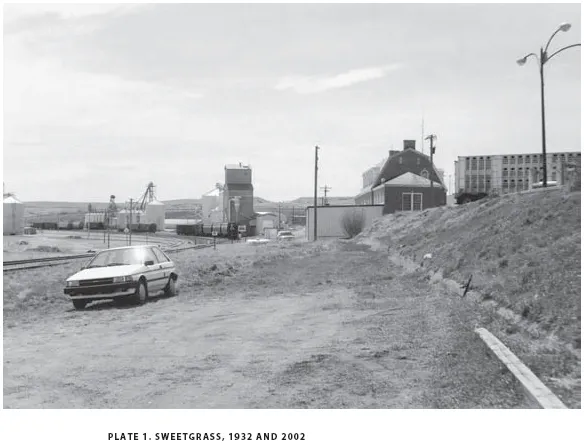

As Lewis and Clark entered the Missouri River canyon two centuries ago, they saw a landscape not fundamentally different from the view captured by a highway engineer in the first half of the twentieth century (pl. 2a). The view shows the broad Missouri River as it exits the mountains, a collection of bordering hay pastures, and a newly improved highway and rail line leading into the mountains. Indeed, the photographer's fine prospect echoes an earlier view gained a few miles farther upstream by William Clark. He described the mid-July scene: “The emence high Precipces oblige all the party to pass & repass the river from one point to another . . . the river confined in maney places in a verry narrow chanel . . . without timber . . . Clifts high and Steep, I assended a Spur of the Mountain, which I found to be highe and dificuelt of axcess, Containing Pitch Pine & Covered with grass.”

The anticipation felt by those early travelers as they entered the mountains remains a part of the modern scene (pl. 2b). The earlier photographer chose his location well: atop a craggy, rocky point that juts directly above the river and the modern highway below (Interstate 15). The grand view still captures the alignment of river, rail line, and roadway. Yet there are differences. Only rotted roots of the pine atop the ridge survived the six intervening decades. Bends in the river shifted slightly. Riparian forests along the river have increased and changed with flood conditions and rural land use patterns. Most dramatically, the modern interstate highway speeds travel through the area in a way unimaginable for Lewis and Clark or even for the more leisurely motorist prior to World War II.

Nevertheless, the long morning shadows play across the grassy hills just as they have for two centuries. The view from the crag still reveals a dramatic juxtaposition of mountains and plains, a place where one western landscape merges with another.

3 CONTINENTAL DIVIDE

Trace a line along Montana's southwest border, from near West Yellowstone to Lost Trail Pass. North of the line, waters drain toward the eastbound Missouri River. Below the line, Idaho streams empty into the westward-flowing Salmon and Snake rivers. The line itself is the Continental Divide, twisting and turning along the summits of the Bitterroots. From Lost Trail Pass, the course takes a sharp eastward bend to Butte. Then it marches northwest, marking the dramatic crests of the Bob Marshall Wilderness and Glacier National Park.

But the divide is more than an arbiter of snowflakes. For Montanans the divide imposes its own bifurcating character and constraints, shaping patterns of movement and environmental adaptation. “West of the divide” describes one set of weather patterns, forest cover, and agriculture, while “east of the divide,” only a few miles away, suggests quite a different natural and human setting.

Crossing the divide is not a casual affair. A steep ascent, a windswept pass, then, brakes burning, a winding downhill grade. Only a dozen paved roads in Montana take you across the divide. The highest road is State Highway 43 at Chief Joseph Pass (7,264 feet), while the lowest is along U.S. 2 at Marias Pass (5,280 feet). The highways are impressive works of engineering, with curves and grades lifting you from cottonwoods and ponderosa pine to aspen and subalpine fir. The roads typically follow rivers as far as possible, then lift up along the mountainsides, ascending the last few miles to the summit. Suddenly, a new vista and it's all downhill.

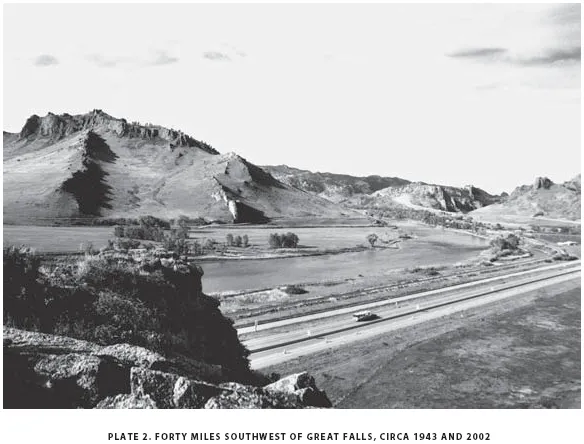

Rogers Pass (5,810 feet) is located along the divide southwest of Great Falls. It holds the unenviable record of being the coldest place in the Lower 48. On the morning of January 20, 1954, the temperature fell to a brisk -70°F. In the early 1920s, the pass was home to a narrow dirt road (pl. 3a). Stunted pine marked nearby hillsides. It was a rocky and austere landscape, in both summer and winter. Eighty years later, mountaintop vegetation had thickened considerably and only the barren road cut in the modern photo echoes the harsher landscape of the earlier view (pl. 3b).

But even today, Rogers Pass is a high and rarefied place, lonely, windswept, beautiful, streaked by swiftly passing clouds. It holds west and east in tender balance, momentarily weighing the fortunes of water droplets before they pass with ease to oceans a continent apart.

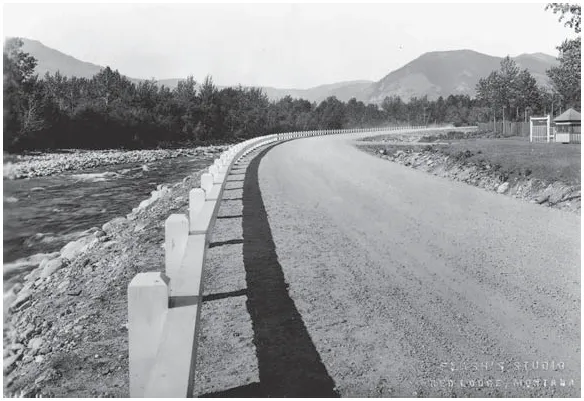

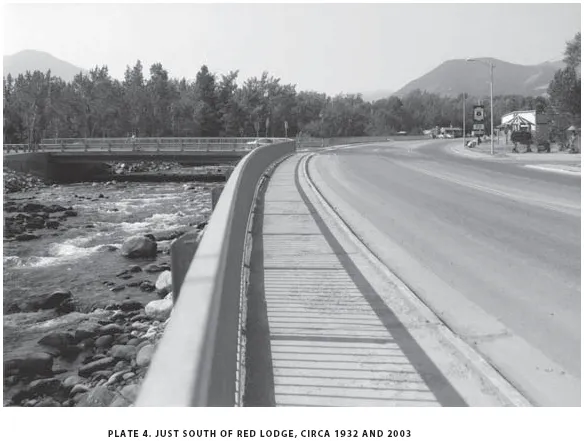

4 LEAVING RED LODGE

Leaving town is just not what it used to be. One of the most profound changes on the national landscape since the 1920s is the reworking and broadening of that shifting boundary between city and country. Eight decades ago, the border between urban and rural was usually well defined. In that earlier American setting, one left town quickly.

On the modern American scene, however, it is no small task to make an exit. Western towns and cities, sprawling for miles in all directions, are particular culprits. Just try and leave Phoenix, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Denver, Salt Lake City, Sacramento, Reno, Seattle, Boise, or Santa Fe. It takes a while! Peripheral clusters of urban activity and endless residential subdivisions blossom everywhere around the blurry borders of such metropolitan areas, true “edge cities,” as journalist Joel Garreau has described them. Smaller towns also reveal an intermingling of urban and rural landscape features, particularly on the advancing borders of fast-growing nonmetropolitan centers. Commercial strips, suburban developments, industrial parks, mini-malls, and small office buildings blend with traditional rural land uses in an increasingly crossbred landscape that is neither “city” nor “country.”

Red Lodge is such a place. The former coal-mining center fell on hard times as the old economy petered out after 1920. Many people left. But a new economy oriented around mountain scenery and outdoor recreation has meant growth for Red Lodge since 1960. Residential and commercial construction has occurred on the edge of the older town and beyond it entirely along nearby streams and scenic hillsides. Golf courses, ski hills, subdivisions, motels, gift shops, cafés, and casinos are accumulating along...