eBook - ePub

Hard Times in Paradise

Coos Bay, Oregon

William G. Robbins

This is a test

Share book

- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hard Times in Paradise

Coos Bay, Oregon

William G. Robbins

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Blessed with vast expanses of virgin timber, a good harbor, and a San Francisco market for its lumber, the Coos Bay area once dubbed itself "a poor man's paradise." A new Prologue and Epilogue by the author bring this story of gyppo loggers, longshoremen, millwrights, and whistle punks into the twenty-first century, describing Coos Bay's transition from timber town to a retirement and tourist community, where the site of a former Weyerhaeuser complex is now home to the Coquille Indian Tribe's The Mill Casino.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Hard Times in Paradise an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Hard Times in Paradise by William G. Robbins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction

To hell with love of country. I compete for myself. People say I should be running for a gold medal for the old red, white, and blue and all that bull, but it's not gonna be that way. I'm the one who has made all the sacrifices. Those are my American records.

The Coos Bay district on the southern Oregon coast is a unique geographic region in one significant respect—it represented the last frontier for a migrating logging and lumbering industry that had its beginnings in the great white pine forests of New England. Since the days of the colonial mast trade, the timbered wealth of the continent has provided the basic raw material for empire building, and it has served as the centerpiece for the commercial and industrial expansion of American capitalism. Products from the forest were as important to seventeenth-century New England shipbuilders as they were to the California home-construction industry after the Second World War.

Operating within a laissez-faire ideological framework, lumbermen were part of the dynamic of an American capitalism that produced a mercurial economic environment of overproduction and cutthroat business competition. Virtually unnoticed in the headlong quest for profits—at least at the time—were the social costs in eroded soils, cutover forestland, tax delinquency, and decaying and impoverished communities. Those insecurities and hardships have persisted, visiting every center of lumbering activity—the river-born mill towns of New England, the sawdust hamlets like Saginaw and Muskegon in the Great Lakes states, the longleaf pine manufacturing centers along the gulf plain, and finally the communities of the Douglas fir region on the North Pacific slope.

That volatile economic world bestowed short-range advantage and opportunity on a mobile work force and then exacted a heavy toll in human misery when the market failed or the investor moved on to new or more profitable sources of wealth. For more than 150 years, the lumber and forest products industry has provided a prime example of migrating capital, rapid liquidation of resources, and boom-and-bust cycles for towns dependent on the forest bounty. That story has a contemporary ring: when the long shadow of want and hardship settled on many of those communities in the 1980s, there were no virgin timber stands beckoning beyond the squeal of the yarding machine; to make matters more difficult, increasingly mechanized and capital-intensive operations are diminishing the size of the forest industry work force.

The lumber trade has left its mark on communities from the Atlantic to the Pacific shores of North America. Lumber entrepreneurs flourished in a culture that provided few restraints beyond the market. Theirs was a world that placed little value on forestry principles that would contribute to economically stable communities. With few exceptions, the industry pursued cut-and-run practices well into the twentieth century and on every successive logging frontier.

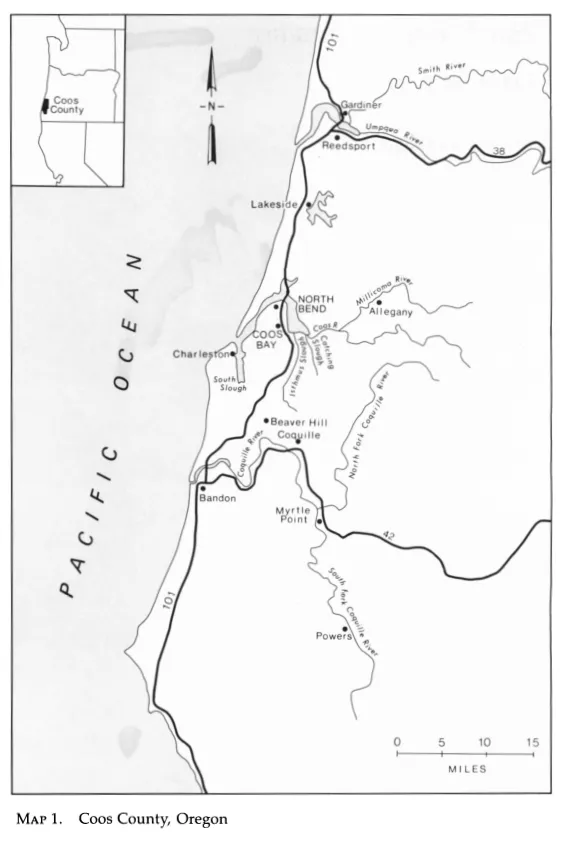

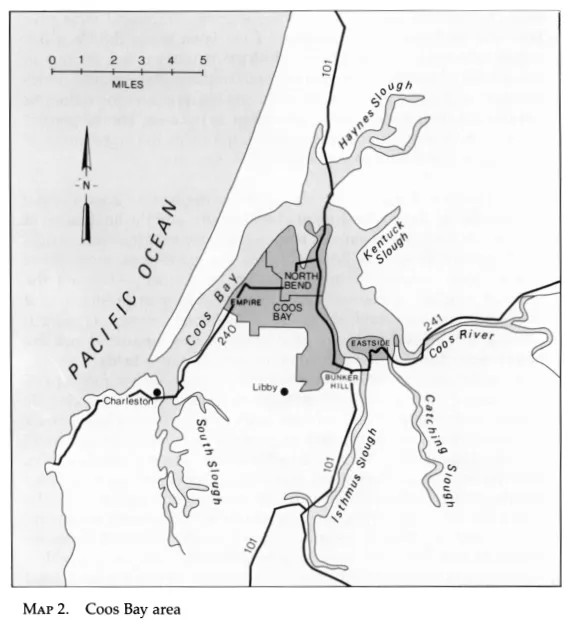

Coos Bay is a semi-enclosed body of water that offers meandering access to the ocean and is located midway between the Strait of Juan de Fuca and San Francisco Bay. The estuary is, in truth, an elongated series of sloughs and tidewater streams where salt and fresh water mix, with tidal action normally causing a slow drift to seaward. The drainage tributary to Coos Bay—approximately 825 square miles—embraces Oregon's rugged Coast Range, which runs north and south in a series of sharply defined valleys and narrow canyons.

A mild, marine climate, with 80 percent of the precipitation occurring between October and March, provides abundant moisture for one of the fastest-growing forest environments in the world. When Indian people dominated the area, Douglas fir, Port Orford white cedar, and Sitka spruce reached water's edge. Tributary rivers and creeks teemed with salmon and trout, and the estuary supported a large variety and an abundant quantity of shellfish and other marine life. To add to the area's attractive bounty for people who would come from another cultural world, quantities of low grade coal lay beneath the hills adjacent to the bay.

Until white fur trappers and traders began penetrating the southern Oregon coast in the early 1850s, the native people—the Coos, a Penutian-speaking group—inhabitated the area around the bay and lived well and peacefully. Adjusting to the rhythms of the natural world and its changing seasons, they skillfully utilized both the estuarine and land resources to provide a rich variety of food and material goods. For centuries they lived in that relatively stable and productive environment, perpetuating certain species and discouraging others. The white newcomers, who first established homes on the bay in the 1850s, eventually altered those ecosystems, and destroyed much of the cultural complex of the native people.

For the past 130 years the Coos Bay area has been the scene of logging and lumber manufacturing, shipbuilding, coal mining, farming, and fishing. All of those activities have shaped the region, but the men and women who worked in the logging camps and mills have been the mainstay of the economy. Their labor made the Coos Bay region one of the leading forest-products manufacturing centers in the world by the middle of the twentieth century. The forested slopes tributary to the bay provided the principal resource and the economic base for the immigrant workers who came to the area. That 87 percent of the region is still forestland today emphasizes the significance of the resource to the southwestern Oregon economy.

The opening of the vast timber stands on the North Pacific slope—to speculation, the establishment of mill towns, and the liquidation of old growth forests—required a large work force to carry on the back-breaking and dangerous tasks of felling the giant trees, moving the logs to mills, sawing them into lumber, and finally shipping the finished product to market. Those men and women produced and delivered the goods, built the towns, established community institutions, and then suffered when the resource was liquidated and the investment capitalist had moved on to more lucrative fields.

A combination of factors attracted people to each new forest frontier, most of them values and attitudes associated with the economic culture of capitalism. Boosters for land companies, spokesmen for transcontinental railroads, and proponents of frontier expansion all described the land to the west as a New Eden, an environment lush with promise and offering the good life to those willing to pull up stakes and head toward the sunset. In the timbered region along the North Pacific Coast, the abundant stands of old growth forests attracted both capital and technical expertise—the two vital forces required to transform the resource into commodities to be shipped to distant markets. Whether they were lumber entrepreneurs, local businesspeople, mill workers, or loggers, they were part of a culture that sought to turn nature's bounty to advantage.

And there were few doubters in the lot. Most believed that those massive timber stands would last forever. In the days when the cedar, spruce, and Douglas fir grew to water's edge, logging operators harvested the forest with reckless abandon, using hurried and careless practices that wrought destruction on both humans and the environment. To magnify the problems of that wasteful and troubled world, periodically depressed lumber prices and cutthroat competition made it profitable to take only the best logs out of the woods. There was no consideration to logging selectively, no thought to the environmental consequences of logging practices, and very little attention to reforesting cutover areas. Lumbermen, bending to the will of an unstable market, carelessly exploited the region's timber abundance in their quest for profits. Those practices were not conducive to a humane social environment.

The pattern of exploitation was set before the lumbermen arrived. From the time the first European venturers sought out the riches of the Northwest Coast 200 years ago, the region has been a centerpiece in the dreams of profit seekers. Its wealth of marine and land mammals offered lucrative trade opportunities to ship captains who plumbed the coastal bays and harbors to exchange trade goods with native people for furs. Those sea otter pelts, bartered in Chinese ports for silks and spices and other goods of value to London and Boston buyers, reaped great rewards for the merchants who underwrote the voyages. More important, that pattern of exchange established a precedent for the future—the region's largely extractive economy would continue to attract outside capital, and much of the wealth gleaned through its exploitation would eventually make its way to metropolitan centers beyond the region.

Capital first created communities in the Pacific Northwest and then milked them of profits when the region's resources were sold in domestic and world markets. When the first white communities were established in the Northwest, local and San Francisco capital financed much of their commercial activity. By the turn of the century that regional autonomy began to erode as eastern and foreign banking interests invested in transportation and resource development.

The extension of transcontinental railroads to the Northwest represents one symbol of that change. Agents of foreign and eastern capital followed the rail lines to the region as entrepreneurs poured money into coastal and Columbia River canneries, and funded the heavy equipment shipped to Idaho mines. To add to that speculative frenzy, Chicago, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and southern lumber capitalists purchased timber and constructed milling facilities along the Pacific Coast.

The Pacific Northwest took on the aura of an investor's frontier as capitalists from far points of the continent sought to tap the region's abundant resources. And the culture that spurred them on offered few words of caution. In western Washington, Seattle, Tacoma, and Olympia mushroomed into metropolitan centers within two decades while the land beyond—adjacent to Puget Sound and the Grays Harbor area—was becoming a vast stump farm as lumbermen turned the forest bounty to profit.

The aspirations of an expansive market economy and its business institutions set those forces in motion and moved people to action. Because that cultural ethos defined all resources as commodities, waterways and estuaries, timbered slopes, and even the resident labor force were valued chiefly for their potential convertibility to market items. Most communities in the Pacific Northwest, however, were not beneficiaries of that process; large capital organizations located at centers of economic power have been able to dominate the less-populated areas where most of the natural wealth lies. Because financial houses and banking institutions—at first in San Francisco, later in St. Paul, and Chicago—provided the capital to exploit those resources, most of the profits were siphoned away. Nowhere is that more evident than in the towns of the timbered back country where residents reaped the social costs in cutover forestlands, eroded mountainsides, and debris-filled and silt-laden waterways.

The movement of capital has become more sophisticated in the last half of the twentieth century as the Pacific Northwest economy has become more closely integrated at the national and international level. The charge can no longer be made that the region's wealth is being drained to the corporate coffers in the East. Today multinational forest products firms, some of them with central offices in the Pacific Northwest, as a matter of common practice shift their investment money to those arenas with the potential for highest return—the logging of southern timberlands, the construction of condominiums and resorts, the building of ocean-ranching facilities, or establishing indoor hydroponic lettuce farms in the Northeast. Meanwhile, the communities creating that surplus capital suffer the consequences. Which is to say that resource capital in the United States (and worldwide) has become increasingly mobile, and investment decisions under those circumstances have been made without community health and stability as a consideration.

The old tale of eastern advantage in the exploitation of western resources and the calculated investments of the multinationals in our present age is only part of the story. More important from a human perspective is what that relation has meant to communities dependent on single industries. That question brings us to the settlements on Coos Bay—communities significantly influenced by investment decisions made beyond the isolated southern Oregon coast.

This book is about the people who made Coos Bay, who forged a culture and tradition not unlike that of other timber-dependent towns in the region. But the bay communities were different in one significant respect; they were the last of the Pacific coastal lumbering centers where old-growth timber provided the raw material for plywood, sawmill, and pulp manufacturing. While other forested areas in the Douglas fir region began to decline as early as the 1930s, the mills on Coos Bay operated three shifts a day into the 1970s.

The people who came to the southern Oregon coast to earn a living and make their homes were part of a broader economic network associated with the Pacific lumber trade. The health and success of that business largely determined the well-being of the south coast communities. In the early years coal mining, and later dairying and fishing, were important ways of making a living. But for most of the period, the logging and lumbering trade was the mainstay of the local economy. The men and women interviewed for this study recognize that fact, and for better or worse, most of them believe that forest products will continue to be the primary economic activity on the bay.

This study is framed in the presence of an area that is experiencing the social stresses associated with high unemployment—a declining population, increased alcoholism, spousal and child abuse, and foreclosures on homes and other personal belongings. The virtually closed housing market in the bay communities of the late 1970s has come full circle; vacant houses, real estate, and for sale signs abound and building construction is at a virtual standstill. Few people are optimistic that conditions will improve in the forseeable future. Increased automation in the mills and a drastically reduced supply of privately owned timber have cast gloom over the future.

U.S. Highway 101 passes through the manufacturing centers of Coos Bay and North Bend. For the tourist, the drive along the industrial waterfront presents a sharp contrast to the windswept vistas of the nearby ocean beaches. For travelers approaching from the California end, the graying, rusting, and silent plywood plants and sawmills stand as mute reminders that not all is well here.

The City of Coos Bay (population 15,000), once a bustling center of forest products manufacturing, does not have a fully operational mill at this writing. Only in North Bend (population 9,000), where the giant Weyerhaeuser plant sprawls along the bay front, is there a sign of industrial activity. Here one sees ships loaded with wood chips and unprocessed logs bound for Asian markets, symbols of the extractive character of the regional economy. The Coos Bay area, proclaimed as the lumber capital of the world following the Second World War, is still dependent on a single industry and, for much of its income, on a single company.

While the communities have brought certain advantages to residents when the lumber market was strong, they have exacted a heavy toll during periods of depression, when building activity was down, or on the occasion of protracted waterfront and sawmill labor disputes. Absentee ownership and management also have influenced the spirit of the settlements and contributed to an element of bitterness, particularly in the wake of the plant closures of recent years. But job instability was inherent to an industry where seasonal layoffs, periodic shutdowns, and business failures were regular occurrences.

When economic disaster struck lumber towns in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1980s, seven out of ten jobs on Coos Bay were timber related, a higher percentage than in any comparable area in Oregon. A Portland Oregonian writer observed in November 1981 that Coos Bay provided “a cautionary example” for the entire Douglas fir region. The Eugene Register-Guard, serving Oregon's depressed upper Willamette Valley, agreed: “Coos Bay's undiversified economy troops in lockstep with the timber industry. For the past two years, the march has been steadily downhill.”1

Today the giant Weyerhaeuser complex, after forcing concessions in wages and benefits from its work force, operates with a sharply reduced crew; every other mill on the bay has either closed or has reorganized under a different corporate title. The new firms are non-union and employ only a few people. Paula Laurilla, who still operates the tavern and rooming house her father established in 1913, worries about the future: “This is the worse since 1932 and ’33. We've had strikes and shutdowns before. But you always knew things were going to be settled and that there would be an end to it. Now you wonder how it's going to turn out.”2

Other people are asking similar questions while the newspaper and the local development agencies pursue new industries for the area. Although Laurilla and many of the older generation in the community still think in terms of the past, events of the last few years have largely destroyed that world.

But Oregon's south-coast residents are a tough, gritty, persistent people, unafraid of hard and dangerous work and always ready “to go down the road” when the boss became overbearing or there were rumors of a better job in the next camp. The late Steve Prefontaine, a graduate of Marshfield High School in Coos Bay and America's premier distance runner at the time of his death in 1975, typifies that tenacious spirit. “His racing style,” a Life magazine article reported in 1972, “reflected the tough, elemental life of Coos Bay, Oregon, the logging town where he grew up.” “Pre,” as he was known worldwide, was a short, cocky maverick who bucked the Amateur Athletic Union establishment in the United States. “To hell with love of country...