![]()

1 / GLACIERS AND GASOLINE

Mount Rainier as a Windshield Wilderness

In the early 1920s, a national park brochure observed that driving around Crater Lake was not “a joy ride, but a pilgrimage for the devotees of Nature.” Touring the lake by car was “a spiritual experience—nothing less.”1 In time Americans would come to question the presence of cars in national parks and their compatibility with wilderness. But at the turn of the century, autos offered a fresh perspective on national parks. Indeed, they helped foster a principle of preservation in which it seemed possible to commune with nature in a car. As auto use rose in national parks, park patrons and managers began to consider the meaning of national parks within the context of the motor age. They began to consider how to reconcile machines in park settings. They were not interested in excluding machines from parks to promote a wilderness experience. Instead, they started to fashion a new set of mental perceptions about national parks in which automobiles made the experience seem possible.

Of all the early parks, Mount Rainier stands out in understanding this process. The nation's fifth national park, established in 1899, it set the pace for interpreting national parks in the motor age. By the time the National Park Service was created (1916), Mount Rainier had not only allowed the first cars into a national park, but also had provided access by road and car in such a way as to emphasize the view from the road and the road as part of a scenic narrative. In this way, Mount Rainier illustrates the transition from an older way of knowing parks, by horse power, to a new way of knowing parks, by motor power. The park is also important in understanding the transition to the motor age because it did so with such apparent ease and speed. This was partly because it lacked the long history of railroad patronage common to other western parks, where transportation companies attempted to retain control of park services and accommodations. But the main reason was that Mount Rainier served a motoring audience sooner than other parks. Mount Rainier was in closer proximity to urbanites than any other park of its time. The park's main patrons were residents of Seattle and Tacoma, who could visit the park in a day by car and typified a new generation of park visitors; they were middle-class, urban Americans whose perceptions of the park were tied to their machines.

At Mount Rainier and other parks, reconciling machines with nature relied on a number of factors. The process required thinking of roads not as the antithesis of primeval nature but as constructions that enabled people to know primeval nature better. Park roads were built with the idea that they both organized and protected park scenery. The process also required thinking of parks, and the landscapes they preserved, as best seen from and experienced through a car. Because automobiles increased the pace and range of park tours, and enabled more people to visit national parks, Americans came to associate autos with appreciating national parks and the natural world. Finally, reconciling automobiles in national parks required thinking of motoring Americans not only as the main audience for parks, but also as essential to their preservation. For better or worse, many agreed that autos popularized national parks, making them truly democratic by opening them to more Americans. Moreover, autos promoted the use of parks for the appreciation of their scenic wonders and in turn protected them from resource development. In the nation's emerging consumer culture, parks had economic value as tourist attractions and wilderness reserves. In these ways, coming to terms with autos contributed to the notion that in the relationship between national parks and automobiles there was potential accord between the machine and wilderness.

THE VIEW FROM THE ROAD: SCENERY, PARKS, AND PRESERVATION

Before autos ever appeared in national parks, there were roads. Roads, physically and conceptually, paved the way for the transformation of parks into special places for automobiles and nature. At the turn of the twentieth century, roads were shaped to be appropriate for parks, but parks also shaped roads—their routes and views—and were even identified as ideal settings for laying roads out. Roads symbolized a form of modernity, in that their construction altered the primitive to make way for human use of nature, and employed the technology of an industrializing society. The justification for and design of roads were key elements of an ideal of preservation through development, which considered roads not as intrusions but as enhancements.

Within the context of nineteenth-century ideas of nature, advanced by park designers such as Frederick Law Olmsted, roads were expressions of the natural world as “scenery,” artistic compositions of the picturesque and sublime, and not nature as wild and unpredictable. In this sense, roads provided a scenic narrative: they organized and selected views for park visitors. As Olmsted noted in his recommendations for Yosemite in 1865 (when it was a state park), public parks should be open to everyone but their scenery preserved from “injury.” Roads allowed this to happen. They protected these reserves by regulating use—concentrating people in specific areas—and presenting nature. In this way generations of tourists would not overrun the park; traveling Olmsted's proposed valley loop road, they would discover the same Yosemite, its “finer points of view” arranged in a predetermined and visually appealing sequence. Without roads, visitors would not have been able to encounter a national park. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, army engineers constructed roads in Yellowstone and Mount Rainier, for example, that conformed to these standards. Routed like paths in a garden, roads were considered less as a disturbance and more as a dramatic contrast to each park's primeval setting. Roads, in effect, “produced” the space we know as a national park.2

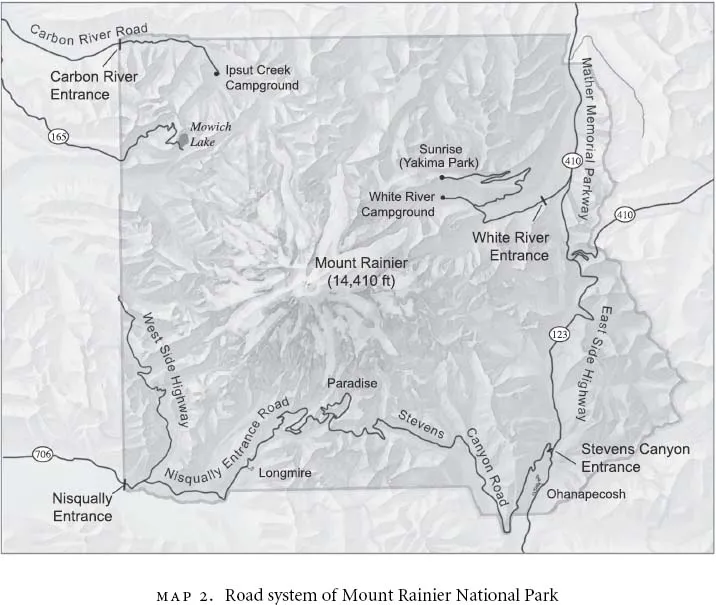

The early development of Mount Rainier National Park's road system reflected the notion that a road was a form of protection for, and an essential element in appreciating, the national park. Construction began on the park's first road, to the subalpine meadows known as Paradise, shortly after the park's creation in response to rising visitation and increasing calls for better access. Paradise was popular because it offered access to the south side of the mountain, considered the easiest route to the summit. But it was even more attractive for its close views of the mountain's glaciers and famous subalpine floral display. Mount Rainier and its unique attributes fit the model for a park envisioned in terms of the nineteenth century: as a cultural icon.3 Mount Rainier's roughly square boundaries enclosed a relatively small area (some 320 square miles) and focused attention on the principal feature: the 14,410-foot, glacier-clad volcano that dominates the skyline of western Washington. In the late 1890s, the naturalist John Muir observed that Mount Rainier possessed all the qualities of an ideal national park, with its sublime and picturesque scenery. The “noblest” of all the Pacific Coast volcanoes, Mount Rainier evoked feelings of awe, he wrote, for its “massive white dome rises out of its forests, like a world by itself.” In contrast to this immense physical presence, a “mountain wreath,” “a zone of the loveliest flowers, fifty miles in a circuit and nearly two miles wide,” encircled Mount Rainier and beckoned outdoor lovers with its beauty. “Nature,” Muir concluded, had created between the dense woods and deep ice “the richest subalpine garden I ever found, a perfect floral elysium.”4

In May 1903, Assistant Engineer Eugene V. Ricksecker, who was in charge of Mount Rainier's road project locally, selected a route up the Nisqually River valley that would lead visitors to Paradise. This way up the mountain was already popular with tourists and climbers. The road entered the park near its southwestern corner and led to Longmire, which had been attracting visitors since the turn of the century with its medicinal springs and views of the mountain. And from there, the road wound up the mountain's shoulders to Paradise. In addition to taking advantage of its popularity, Ricksecker justified his selection of the route because it would open the park to the greatest number of people. The roadway offered the main connection with Tacoma, the largest city near the park.5

Besides these practical considerations, Ricksecker was particularly responsive to the quality of the road's design because it would contribute greatly to how tourists perceived the mountain as a national park. Reflecting the basic philosophy noted above, the engineer chose a route intended to display the park's sublime and picturesque scenery. He also expressed concern for protecting the natural environment through which the road would pass. In this, he was indebted to the work of Major Hiram M. Chittenden. Chittenden, his supervisor, oversaw the construction of Yellowstone's system of roads and bridges from the late 1880s to the early 1900s. Chittenden, himself indebted to park designers like Olmsted, established an ideal of construction in which roads did not mar the park landscape; roads should instead lie gently on the land. Chittenden believed that all road work should enhance the visitor's appreciation of scenery. Roads organized the park tour, the natural scenes and wonders, that visitors would see. And as part of this goal, he thought it essential that road builders consider the aesthetic impacts of construction.6

In his survey, Ricksecker portrayed the road to Paradise as different from other roads because it was in a national park. Its location and design would emphasize its scenic rather than commercial purpose. He envisioned it “solely as a pleasure road” for “the enjoyment of the people.” It would make “more accessible the summit of Mt. Rainier, and its surrounding grandness.” Rather than taking “the shortest practicable route” between two terminals, the road instead would rise from Longmire and reach Paradise through a meandering series of switchbacks that conformed closely to the mountain's topography and connected several points of outstanding scenery. It would take visitors through lowland forests and up the south flank of the mountain, past the snout of a glacier, rushing waterfalls, and striking vistas, until reaching the alpine meadows of Paradise.7

Like those employed in developing Yellowstone's roads, Ricksecker's plans showed an interest in both preserving and presenting the mountain's scenic grandeur in such a way as to make the road appear part of the mountain. He explained that it would follow “the graceful curves of the natural surface of the ground,” for these were “most pleasing and far less distractive than the regular curves laid with mathematical precision.” Other construction details would contribute to the road's rustic appearance as well. To diminish the sense of barrenness and artificiality that a swath of some sixty feet would create through dense forest, Ricksecker directed that a few of the finest trees should be left standing. He also noted that no borrow pits (holes created for fill dirt) should be made and that no material from excavations for the road cut would be used to build the road surface, reducing unnecessary scarring. His choice of the mountain's ubiquitous volcanic rock for surfacing the road added to the natural appearance, as did his selection of native stone for the construction of retaining walls and guard rails, and wood for the road's many bridges.8

Ricksecker's construction specifications combined the practical with the pleasurable to ensure that park visitors traveled safely and comfortably, and that their attention was drawn to the scenery instead of to the road. By allowing the road to follow “its own course” as much as possible, Ricksecker believed that the road would not only appear natural, but the traveler would also be “kept in a keen state of expectancy as to the new pleasures held in store at the next turn.” In order to ensure the road's “natural” quality and to make travel along it enjoyable, the engineer settled on a gentle gradient. Following a standard set by Chittenden and the army engineers in Yellowstone, the grade of 4 percent would accommodate wagons and other horse-drawn vehicles. The grade and mode of travel in turn influenced what scenic features were seen from the road. The route should link “all points of interest that lend themselves readily to the scheme,” the engineer noted, without adding too much distance. Ricksecker recognized that in order to maintain the attention of wagon-bound travelers, changes in scenery “should be kaleidoscopic. Steep stretches where teams must walk soon become monotonous and pall upon the senses. Light grades offer no excuses for the teamster to walk his horses.”9

For this reason, Ricksecker conceived of travel along the road, up one of the nation's highest mountains, as an unfolding panorama, one he and his crews pieced together on the ground and then rendered on a map. The engineer described this process as one in which the road transported the traveler from forest floor to alpine meadows in a gradual climb in which each foot of elevation gain created a more expansive view of the mountain and surrounding terrain. Speaking of the section of road above Nisqually Glacier, for example, Ricksecker observed that an “extended view of the lower Nisqually country opens up; the first close view of the mountain and its Southeasterly slopes is obtained, and a superb view of Nisqually Glacier [meets the eye].… The trees are sparse, just thick enough to keep one alert to… the best views.”10

Despite the imagined naturalness of the road, nature itself appears only as tapestry in Ricksecker's writings and, for that matter, in those of Chittenden and other park designers of the period. Nature is the scenic canvas of forests, glaciers, and waterfalls that the road crosses. In the setting of such a natural icon as Mount Rainier, the road appears minuscule but symbolizes by its mere presence the triumph of technology in the wilderness. It is this element that illustrates best how Ricksecker and others of his time viewed the road and the mountain as complementary forms of the sublime. The road was, in a sense, a stage that dramatized the unfolding scenic narrative. By its sheer scale, Mount Rainier did not appear threatened by the road, while at the same time the road transformed the mountain into a spectacular backdrop.11

The contrast between road and mountain, among other things, underlay Ricksecker's concept of the road to Paradise specifically, and of a road system for the entire park generally. He envisioned Mount Rainier as having an extensive network of roads. In time, he thought that many of the local routes leading into the park should be improved. In addition to the Nisqually River valley, the engineer learned of a number of access routes into the park during the initial stages of his survey, among them a trail up the Carbon River from Fairfax, a wagon road and trail up the White River from Enumclaw, and a wagon road up the Naches River (near what is today Chinook Pass) from Yakima. He also expressed the possibility of a road into the park from the southeast by way of a wagon route and trail along the Cowlitz River and Ohanapecosh Creek. Along with the Nisqually entrance, the routes would eventually form the principal entrance points into Mount Rainier—at the square park's four corners.12

More importantly, Ricksecker imagined a scenic road encircling the mountain that would ultimately link up with these entrance roads. The engineer, who made his proposal in December 1904, explained his vision in idealistic rather than practical terms. A high-elevation road around the mountain, constructed as close as possible to the permanent snowline, would offer diverse and alternating scenery. In contrast, a lower route passing primarily through forest, as recommended by another army survey, would be “more or less monotonous.” Since a section of the road he surveyed already passed through forest, the engineer believed that it would be “with a certain sense of relief that the tourist will welcome the coming into the open with the opportunity to see out and over such an expanse of rugged country as is here to be seen, and I can imagine no more thrilling exhilaration than a ride along the summit of the Cascades and the glacier dividing ridges.”13

By mapping the route in his mind and on paper, the engineer made the road encircling the mountain seem more real and further suggested the intimate connection between the road and natural landscape. His vision in many ways was farsighted—a road around the mountain would intrigue park administrators and park supporters for some time to come, in part because it would bring the mountain to the people. Although it reflected Chittenden's plan for the Grand Loop Road in Yellowstone, Ricksecker's proposal also expanded upon the concept. Ricksecker's road would encircle the park's primary feature, the volcanic cone, and provide as many views of it as possible. It would present the mountain from a well-graded road, incorporate it into a familiar type of experience and setting, and thus enable visitors to know the mountain better ostensibly without harming it.14

But the reality of road construction demonstrated the limits of this vision. Work on the twenty-five-mile road to Paradise began in 1904. Ricksecker had seriously underestimated the cost of construction, and from the outset road work encountered the difficulties presented by short seasons, rough terrain, and contract labor. Chittenden was called on to oversee the project in 1906 and, as Ricksecker's superior, would be often credited with its construction and that of the proposed road around the mountain.15 Chittenden concluded that Ricksecker's design details—the road's width of twenty-five feet and its complex “system of berms and drains” for example—were entirely too elaborate, refined, and expensive for a park road in “this wild and rough country” and were better suited to a city highway. The senior engineer also thought that the wagon road between Ashford and Long-mire, essentially the park's entrance road, was the worst he had ever traveled. Chittenden ordered Ricksecker to revise construction standards and adjust priorities to make reconstruction of the lower portion of the road his highest priority. Ricksecker complied, and by the following year the road from the park entrance to Longmire had been improved. By 1908, road construction had been completed to the snout of Nisqually Glacier, making the route the first American road to reach a glacier. By 1910, the Nisqually Road (as it was later called) was complete as far as the Paradise Valley, but the section above Nisqually Glacier was too narrow for safe travel and would not open to automobiles until 1915.16

The road to Paradise was by no means a first-class road, and it would undergo considerable r...