![]()

1

Liberal Plunder

A RECURRING Q’EQCHI’ HISTORY

Pilar Ternera let out a deep laugh, the old expansive laugh that ended up a cooing of doves. There was no mystery in the heart of a Buendía that was impenetrable for her because a century of cards and experience had taught her that the history of the family was a machine with unavoidable repetitions, a turning wheel that would have gone on spinning into eternity were it not for the progressive and irremediable wearing of the axle.

—Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Progress, far from consisting of change, depends on retentiveness. . . . Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

—George Santayana, The Life of Reason, vol. 1

ON a recent flight to Guatemala, seated to my left were two middle-aged gringos dressed in overalls who appeared to be on a volunteer trip to build a church. In front of me was a group of young men with military haircuts planning some kind of expedition; in fact, “kaibiles,” soldiers from Guatemala’s special operations force, met them at the airport’s baggage claim. Seated behind were a couple of businessmen intently discussing strategies for the newly privatized telecommunications system in Guatemala. Like the recurring characters in García Marquez’s epic novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, my three sets of neighbors on this plane seemed like a reincarnation of the original Spanish invaders—missionaries, military conquistadores, and colonial officials.

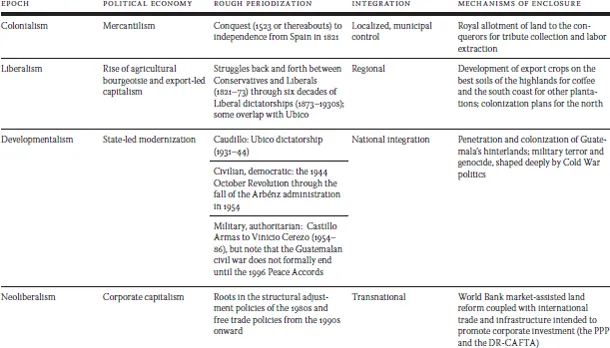

As the conquistador Bernal Diaz once described it, their goals were “to bring light to those in darkness, and also to get rich, which is what all of us men commonly seek” (quoted in Farriss 1984: 29). Regardless of which outsiders happen to hold power, the everyday lived experiences of Maya people have changed little (ibid.). Indeed, for the average Q’eqchi’ farmer, the experience of dispossession has been remarkably consistent over the epochs. Through multiple conquests in the name of God (Christianity), gold (commerce), and glory (civilization) (Hecht 1993), outsiders have repeatedly sought to enclose Q’eqchi’ territory, not only for the value of its fertile land, but also for the corollary control of the labor of its people (Taracena 2002). These interlopers consolidated and replicated their agrarian power during the three key moments in Guatemalan history preceding neoliberalism that are described in this chapter—colonialism, Liberalism, and developmentalism1 (table 2). While the repetitive nature of these multiple histories of enclosure may make them seem inevitable in retrospect, Q’eqchi’ people also repeatedly resisted their dispossession.

FIRST ENCLOSURE: CONQUEST BY CHRISTIANITY

Before the Spanish conquest, Q’eqchi’ people likely lived around a 1,500-meter altitude in the elongated valleys between (present-day) Tactic and San Cristóbal and between Cobán and San Pedro Carchá. Located in a strategic zone between the northern lowland forests, the Atlantic ocean, and the densely populated western Guatemalan highlands, Q’eqchi’ people took advantage of their geography by working as highland-to-lowland traders from at least the early Classic period (300–600) (Wilk 1997). Early writings by Spanish conquerors comment on Q’eqchi’ involvement in long-distance commerce in cotton, chocolate, and annatto (Bixa orellana), and other forest and agricultural products, all of which traveling Q’eqchi’ merchants (“Cobanero” salesmen) continue to trade today. Little else is known about precolonial Q’eqchi’ political organization except that it was less hierarchical than more powerful city-states such as those ruled by the K’iche’ and other western highland groups; this may help explain why the Spanish found the Q’eqchi’ so difficult to conquer.

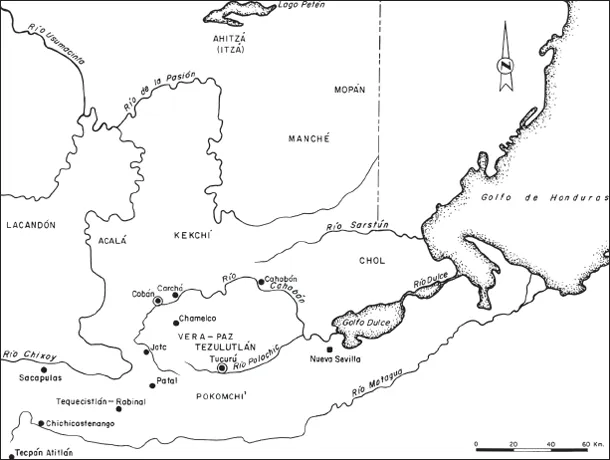

By the 1530s, the Spanish had established dominion over most of Guatemala except for territories belonging to the “unconquerable” Lacandón, Acalá, Mopán, Itzá, Manché Ch’ol, Pocomchi’, and Q’eqchi’ peoples (fig. 1.1).2 Spanish conquest broke down these boundaries—either through forced resettlement or through mutual Maya resistance and flight—and leveled America’s diverse mosaic of civilizations into a single category of rural “Indians” (Bonfil Batalla 1996). The people perceived to be “the Q’eqchi’” today were clearly influenced by their cultural and linguistic interactions during the colonial period with other neighboring groups, particularly the Manché Ch’ol and Acalá. The Spanish coveted Q’eqchi’ territory, in particular, as a staging ground for taking control of the expanse of forest that stretched from Chiapas, across Petén to Belize, and down into part of the Verapaz and Izabal departments between the Sierra de Chinajá in the west and the Motagua Valley in the east (Sapper 1985). After several failed forays into the Q’eqchi’ region, the Spanish retreated and renamed this frontier the Land of War, or Tezulutlán. The Spanish inability to conquer Q’eqchi’ and surrounding lowland peoples militarily sparked the interest of Fray Bartolomé de las Casas (1474–1566), a farmer turned Dominican priest.

TABLE 2. Summary of Q’eqchi’ Enclosure by Epoch

FIGURE 1.1. Ethnic groups, circa 1550. Source: André Saint-Lu, “La Verapaz, Siglo XVI,” in Historia General de Guatemala, vol. 2: 628, illustration 175. © Fundación Herencia Cultural Guatemala, Archivo 1359

De las Casas had gained fame as the first Spaniard to chronicle and condemn the atrocities of conquest he witnessed as a Hispaniola settler. Traveling back and forth to Spain for religious and legal study, he advocated before the pope and King Charles V for more humane treatment of the native peoples of the Americas and proposed “peaceful” religious conversion as an alternative means of conquest (Todorov 1984).3 Returning to the Americas in 1535, de las Casas accepted the challenge of Guatemala’s Spanish rulers to prove his theories in the Land of War. According to a fellow Dominican priest named Remesal (for other histories, see Pedroni 1991; Gomez Lanza 1983; Biermann 1971; and Dillon 1985), de las Casas purportedly initiated his peaceful conquest in 1542 by teaching a musical poem about the life of Jesus to four traveling K’iche’ merchants whom he sent into Q’eqchi’ territory with the usual Spanish trade goods (axes, machetes, pots) and trinkets. These singing bards sparked the interest of local rulers, or “caciques,” who invited the Dominican priests to visit. Leading the delegation, Bartolomé de las Casas convinced the caciques to convert to Christianity through baptism by offering them the privileges of Spanish nobility and protection from Spanish settlers (Biermann 1971: 467).

By 1545, Dominican priests claimed to have pacified Tezulutlán. Through papal bull, de las Casas became bishop of this new Episcopal province along with Chiapas. Renaming the region Vera Paz (Land of True Peace) in 1547, Charles V granted the Dominicans control of the area and banned Spanish settlers from claiming landed estates known as “encomiendas.” Elsewhere, these land allotments included not only the right to use the soil but also exclusive rights to enslave local indigenous labor; as Severo Martínez observed in his history of Guatemala, “Indians were part of the landscape” (Mauro and Merlet 2003: 7).

Having consolidated political control over the region, Dominican friars began resettling Q’eqchi’ and neighboring lowland Maya groups into forced resettlements, what they called “reducciones” (literally, “reductions”). By 1574, they had established fifteen nucleated towns, separated by approximately a day’s travel on foot (A. King 1974), which remain the municipal centers of contemporary Verapaz. Invented by Guatemala’s Bishop Francisco Marroquín, forced resettlement became a common colonial administrative practice for facilitating indoctrination of the indigenous population, tribute collection, and seizure of native lands—a concept akin, one might argue, to the so-called model villages established by the Guatemalan military in the early 1980s.

Though portrayed as a peaceful means of religious conversion, this resettlement process almost always required violent enforcement to prevent Q’eqchi’ families from fleeing back to their villages (A. King 1974). Spanish captain Tovilla described how he assisted one Dominican raid: “We burned all their houses. We took all the corn the carriers could bring. We destroyed the milpas. . . . So they are well punished and will be obliged to be peaceful, unless they want to die because we didn’t leave them anything to eat or any metal tools with which to cultivate the land again” (Scholes and Adams 1960: 166). Although the Dominican order forbade friars to inflict corporal punishment, they called upon Spanish authorities to administer lashings and organize forays into the un-Christianized northern hinterland (Biermann 1971). Historians applaud de las Casas for a 1541 decree prohibiting the forcible relocation of native peoples to unfavorable climates, but, in practice, Dominican priests did not always respect this policy (Sapper 1985, 2000). They also transformed the Q’eqchi’ economy in order to fill Church coffers. Emulating Spanish conquistadores, the Dominican priests started demanding tribute in 1562 (Cahuec del Valle et al. 1997) and reorganized the Q’eqchi’ into religious brotherhoods (“cofradías”) for this purpose (Scholes and Adams 1960). Although the brotherhoods eventually became a potent symbol of Maya identity in the twentieth century, Q’eqchi’ people initially resisted the economic burdens of organizing the required religious festivals. Dominican priests also wrote about their frustrated attempts to get their Q’eqchi’ subjects to plant foreign fruit trees such as oranges, citron, lemons, peaches, and quince (A. King 1974)—foreshadowing the complaints of contemporary development agents about Q’eqchi’ disinterest in agroforestry projects.

In addition to such everyday forms of resistance, there were regular armed uprisings in the Dominican forced resettlements. When the priests temporarily left the area, Q’eqchi’ people burned down the first church de las Casas had built in Cobán (A. King 1974). The denial of a 1799 Q’eqchi’ petition to remove the names of dead people from the tribute rolls provoked another revolt in Cobán in 1803, which led to the assassinations of the mayor, the military commissioner, the governor, and a prominent merchant (A. E. Adams 1999; Bertrand 1989). The most common form of Q’eqchi’ resistance to tribute requirements was to flee into the forest, making it difficult for the Dominicans to maintain accurate census records.

Q’eqchi’ flight may also have been an escape from epidemics of European diseases. Unfortunately, the real scope of the demographic collapse of the Q’eqchi’ and other lowland groups will never be known, as the Spanish conquerors burned pre-Columbian Maya books and records. Nonetheless, most historical demographers estimate that nine-tenths of Native American peoples died within a century of European contact from disease, violence, and ecological devastation (Crosby 1972). Perhaps 90 million native peoples had perished by 1600, making it the greatest relative holocaust in the recorded history of humanity (R. Wright 1992: 14). Recognizing that European diseases might have been spread through Spanish military forays along the Belize coast in 1507, up to Lake Izabal in 1508, and through to Petén in 1525 (G. Jones 1997), George Lovell and Christopher Lutz (1995) estimate the combined population of Verapaz and Petén at 208,000 people immediately preceding contact. Just three decades later, the figure had fallen apocalyptically by three-quarters to 52,000 in 1550 and continued to plummet. Once Dominicans established a permanent presence, the census of “tributaries” (probably referring to male heads of household) in Alta Verapaz fell again by half, down from 7,000 households in 1561 to just 3,535 in 1571. That community and ritual life survived at all reveals the resilience of Maya traditions (Nations 2001: 463).

In other ways, colonial life under the Dominicans was comparatively easier for the Q’eqchi’ than for other Maya groups under direct Spanish rule. Due to the emphasis on religious conversion, the Dominicans provided education for both boys and girls, and many nineteenth-century travelers’ reports commented on the unusually high rates of urban Q’eqchi’ literacy. The Dominicans ended forced resettlements in the 1760s, allowing families to live on their farms most of the year so long as the men returned to town for religious festivals and tribute payments (A. King 1974). Not until Guatemala’s recent civil war did the Q’eqchi’ area become significantly re-urbanized, as people fled violence in the countryside for more anonymous and safer urban residences.

Although their entire territory technically belonged to the Spanish Crown, Q’eqchi’ people were able to maintain their traditional, community-based land management under Dominican rule. This would have grave unforeseen consequences for the Q’eqchi’ in the late nineteenth century, when the Guatemalan government decided to reassert its claim over untitled land. Unlike highland Maya groups, who began using the judicial system to protect their community lands from Spanish settlers in the 1500s, Q’eqchi’ people had no legal experience defending their territory and were, therefore, disproportionately hurt by government land expropriations starting in the 1870s. Nonetheless, another peculiar fact of colonial history also provided many Q’eqchi’ with an escape—migration into the northern Maya lowlands.

Although the Dominicans pacified the Verapaz region by the mid-sixteenth century, the northern hinterlands remained both spiritually and militarily unconquerable. Neither from the north (from Yucatán) nor from the southeast (from Comalapa) could they manage to convert or conquer lowland Maya populations across this thickly forested region. Considering Manché Ch’ol resistance to be less “ferocious” than that of the Mopán, Lacandón, and Acalá peoples, the Dominicans made regular expeditions into Ch’ol territory in the early seventeenth century. By 1633, they had converted some six thousand Ch’ol “souls,” but Ch’ol people continued to flee back to the forest (Sapper 1985), while other unconquered groups repeatedly attacked the newly pacified settlements.

Exasperated by this lowland resistance, in 1692, the Council of the Indies issued a final and definitive order to conquer and convert the lowlands and sent troops from Huehuetenango and Chiapas to undertake the task (A. King 1974). During a five-year campaign culminating in 1697 with the conquest of the Itzá in Petén, the Spanish rounded up Mopán peoples from southern Belize and resettled them around Lake Petén Itzá (G. Jones 1997). They resettled the Ch’ol in Urrán, a distant and inhospitable valley above the Motagua River, where they died of disease and starvation (Sapper 1985). Lacandón and Acalá prisoners were moved to Cobán, eventually losing their identity and language to Q’eqchi’ cultural assimilation (ibid.; Cahuec del Valle et al. 1997).

In addition to cultural jumbling in the urban resettlements, there was significant intermixing among remnant groups in the forest frontier, especially between eastern Q’eqchi’ people and the Manché Ch’ol. Based on evidence from Otto Stoll, J. Eric Thompson (1972) suggests there were two different “stocks” of Q’eqchi’ people: those from the highland Cobán region and those he calls “Q’eqchi’-Ch’ol” people from the lowland Cahabón area. One elder and his wife from a Q’eqchi’ village in southern Belize told me a story of having given lodging about fifty years ago to a “Ch’ol” man who came to visit them when he got lonely in the forest (Grandia 2004b; for other stories, see Wilk et al. 1987; Schackt 1981; Danien 2005). While it is unlikely that any unconquered Manché Ch’ol people survive today, the depth and breadth of Q’eqchi’ people’s contemporary knowledge of hunting, fishing, agriculture, and especially healing with medicinal plants in the Atlantic coastal region certainly indicate that they had a long history of interaction with northeastern forest people (cf. G. Jones 1986).4 The astonishing migration of Q’eqchi’ people into Izabal and Belize all the way to the Atlantic coast in response to their next enclosure certainly suggests that the Q’eqchi’ had some prior knowledge from the Manché Ch’ol about this lowland rain forest and ocean habitat.

SECOND ENCLOSURE: CONQUEST BY COMMERCE

After Guatemala gained independence from Spain in 1821, a protracted struggle commenced between Conservatives, who wanted to uphold the power of traditional colonial elites, and anticlerical Liberals, who felt it was necessary to undermine the power of the Catholic Church in order to transform Guatemala into a modern, capitalist economy (A. E. Adams 1999). These terms are capitalized here to emphasize that Conservatives were conservative not in the contemporary, political sense of wanting to uphold traditional religious and personal ethics but in the nineteenth-century sense of hoping to maintain the traditional economic power of estate owners along with Catholic authority and landholdings. Likewise, Liberals defined themselves not in the contemporary, progressive sense but rather as members of the ruling elite who felt that foreign investment and immigration were the ideal path to modernization. Put another way, Conservatives wanted to rule by caste, Liberals by class. Unlike other regions of Latin America where leaders sought to assimilate the rural, indigenous populations, Guatemala remained ethnically stratified—with indigenous land and labor subordinated to elites, both Liberal and Conservative (Weaver 1999).

When Liberals seized power briefly after independence, they attempted to expropriate indigenous common lands as well as Catholic Church properties so that they could reward foreign investors with large land grants. They passed an 1824 law inviting “all foreigners that may wish to come to the United Provinces of Central America . . . to do it in the terms and the way which may best suit them,” including free land grants and tax exemptions (Fuentes-Mohr 1955: 27). In order to speed the pace of European settlement, President Mariano Galvez (1831–38), for example, concessioned more than half of Guatemalan territory—includi...