![]()

CHAPTER 1

Lessons in Constructive Resistance

ON a rainy day at the end of November 1882, thirteen-year-old Esther Clayson held her baby sister as her mother helped them board the Gem, the steamer that was taking them away from the logging town of Seabeck, Washington Territory, and from Esther's father, Edward. With money saved in secret, they left the house as if they were going shopping in town. Then they kept going, first by ship and then by train to Portland, Oregon. This “getaway” became the climax of Esther Clayson Pohl Lovejoy's unpublished autobiography of her childhood, an account that traces her experiences in two intersecting worlds. One world was the verdant garden of Washington Territory, where Clayson explored life with her three brothers, scampering about on wrecked ships and making games of adventure last into the dark hours of the summer nights. In the midst of stunning mountains and Puget Sound, and in the luxuriant growth of the woods near Seabeck, the natural world opened to Clayson's young senses and mind. But another, overlapping childhood world involved abuse and loss, painful power struggles and work for survival, hard lessons in what she would later call constructive resistance.1

Esther Clayson traced her family origins in the rhythms of work, family, migration, and the politics of social class. Her mother, Annie Quinton Clayson, was born August 9, 1845, in Portsmouth, England, to John Quinton and Polly Woodruff.2 The Quintons were a working family of tailors and seamstresses in this vital British navy port town. Annie was “born with a tailor's thimble on her finger,” Esther recalled later. “It was no shining silver tip, but a strong practical instrument with a hole in the end, like her father used to support his large family.” As the oldest of eleven children, Annie began helping her father in his Portsmouth shop at the age of five and was soon assisting her aunt, a Paris-trained dressmaker. By the age of fifteen Annie was skilled in tailoring, dressmaking, and other arts of the needle.3

Esther's father, Edward Clayson, was born on July 10, 1837, in the village of Bridge, southeast of Canterbury in the county of Kent, England, one of sixteen children of Charles and Esther Hughes Clayson. Charles worked as a gardener on a local estate, and the family maintained a kitchen garden and livestock at home. The large number of children increasingly taxed family resources. When one of his sons picked a “rare blossom” from the estate and offered it to the landlord, Charles lost his job. “Cold and hunger finally forced the family into the poorhouse,” Esther recalled, “where they developed an undying hatred for overseers and a lasting sympathy for inmates.” Edward and two of his brothers absorbed these lessons and decided to join the Royal Navy as a way out. Edward started service as a cabin boy, then achieved the rank of able seaman and served in the Crimean War.4

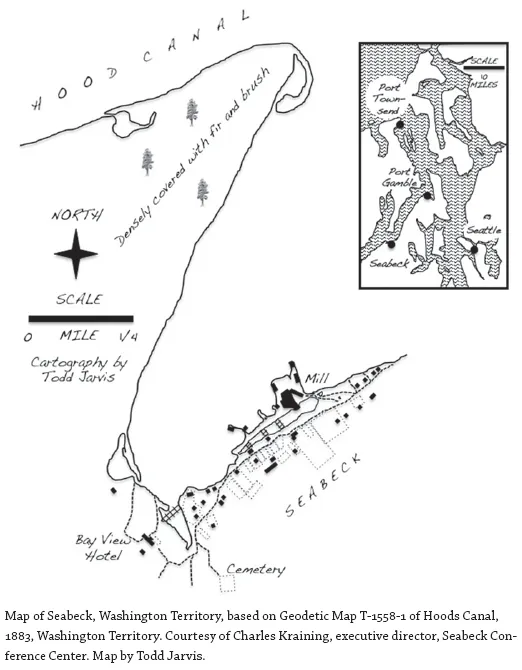

Annie Quinton met Edward Clayson when he came to Portsmouth to sail for duty in British Columbia. “It was love at first sight with both of them,” Esther claimed, “and trouble from the start.” They married in 1864 and rented a small house across town from Annie's family in Portsmouth. Three weeks later Edward left for duty at sea, bound around Cape Horn for the Pacific Northwest coast. Annie contracted with a neighborhood tailor for piecework, and Edward Jr., called Ted, was born in 1865. Annie then received word that her benefits allotment was at an end because Edward had left the Royal Navy. But soon “one enthusiastic letter after another” began to arrive from Port Gamble, Washington Territory, a place Edward considered “the richest and loveliest corner of the world.” He was working for the Puget Mill Company on Hood Canal, and his descriptions of a land of abundance were enticing. Ten years of hard work in the fruitful Pacific Northwest, he told Annie, would allow them to return to England with a comfortable nest egg.5 With this dream in mind, Annie and two-year-old Ted made the voyage to Washington Territory in 1867. Annie understood this to be a temporary sojourn before her return to Portsmouth, where she could provide a comfortable home for her extended family.6

Edward won the contract to carry the mail between Port Gamble and Seabeck and soon moved the family to property he purchased across the inlet from Seabeck's Washington Mill Company.7 He delivered the mail by sailing sloop or rowboat and lost the contract in 1870 when men with faster and more efficient steamboats outbid him.8 Esther's wealthy uncle, William H. Clayson, a captain in the Royal Navy serving with the coast guard in China, staked a new business venture by shipping tea to his brother Edward, who then sold it at ports along Puget Sound.9 But the tea venture was precarious at best and lasted only a short time. Whether delivering mail or tea, Edward drank along the way and ended the day at the bar with friends. Knowing that Edward was spending the family savings, and hearing rumors of gambling debts, Annie wrote to her brother-in-law, telling him to stop sending tea.10

Edward's shifting employment was unsteady, but Annie's industry was the family bedrock. In Port Gamble she went from sewing by hand to using the latest hand-cranked Singer sewing machine, and when the family moved to Seabeck, Annie took her business with her.11 The machine was both a companion during Edward's frequent absences and the tangible symbol of her earning power that would take them back to England.12 Annie could make almost any garment, from layettes to dresses, suits, and burial shrouds. Esther recalled that she made skirts and petticoats “with tiers of ruffles or rows of pleating, and uncounted lengths of such frills and flounces passed over the plate of her machine.” The real moneymakers were shirts for loggers sewn from big bolts of red, blue, and gray flannel brought in from Victoria, British Columbia. Annie Clayson's shirts had distinctive trademarks: high-quality work with a particular “finish of the buttonholes, a herringbone stitch on the collar, or an embroidered design in a contrasting color on the breast pocket.” High demand for her work caused sales of the mass-produced “shoddy shirts” at the Washington Mill Company store in Seabeck to plummet.13

Annie's work and earnings were particularly important because the Clayson family grew by four additional children in these years. “Morning-sickness was the beginning, and homesickness the end of many of her days on Hood's Canal,” Esther recalled.14 William, the second child, was born in Port Gamble.15 Esther was the first to be born in Seabeck, on November 16, 1869, then Fred, his mother's favorite and Esther's shadow in work and play, and then came Annie May, who, Esther noted, “belonged to our family but not to our gang” in the Seabeck years.16

The Washington Mill Company at Seabeck was part of the extensive Puget Sound extractive lumber industry established in the 1850s. Brokered and administered in San Francisco, it was big business and expanded steadily in the second half of the nineteenth century. By the 1880s, according to historian William G. Robbins, the lumber industry “underwent a technological revolution…that vastly increased production and provided manufacturers with readier access to markets.” Railroads provided transportation and land grants. These developments paved the way for the “capitalist transformation” of the region.17 San Francisco investors established the Washington Mill Company in 1857, and the mill fed a global appetite for lumber products and also engaged in shipbuilding for the carrying trade until it burned completely in 1886 and was abandoned.18 Seabeck was part of a cluster of “little kingdoms” such as Port Gamble and Port Madison in Kitsap County, “where the lumber companies managed affairs as they saw fit” and workers lacked power. In this exploitative lumber economy, mill managers such as Sea-beck's Richard Holyoke were “the representatives of colonial powers,” according to historian Robert E. Ficken, “administering economic decisions made in distant San Francisco.”19

With some 250 residents in 1880, most of whom were Euro American (native born and first-generation immigrants) and male, Seabeck was a company town.20 In 1870, 93 percent of Kitsap County residents were either directly employed by the Washington Mill Company, were directly related to someone who worked there, or labored in industries that supported the mill. Ten years later, over 86 percent of residents were still tied to the company. The mill administrators controlled county politics and elections with a heavy hand and influenced county commissioners whose fortunes depended on the mill's success.21 The company store sold up to $10,000 worth of merchandise per month in the 1870s, with well over half of the items sold on credit. The store reported over $20,000 in profits in 1877.22 The workers did not stay long. From 1868 to 1876 some 83 percent of mill employees left within a year or less.23

Edward Clayson had started his new life in Washington Territory working in the Port Gamble sawmill. He left the mill hoping to gain independence and make a solid living by carrying the mail and then selling tea.24 After both failed, in the early 1870s he established a logging camp on his acreage across the small bay from Seabeck to sell lumber directly to the Washington Mill Company. Between eight and fourteen such camps operated along Hood Canal, and the mill owners had a monopoly on most of the lumber they cut.25 As men came to work for the Clayson logging enterprise, Annie opened a boardinghouse to shelter and feed them. “The pretty little house with two dormer windows projecting from the roof and looking eagerly over the bay had not been designed for a logging-camp,” Esther recalled, “but with father as architect it developed sprawling wings to serve this new purpose.” One wing became a dining and living room, and the loft above was fitted out with sleeping bunks furnished with straw tick mattresses.26

The Clayson logging camp was to be the primary family business, but Annie's camp boardinghouse grew steadily by its side. Annie learned how to feed a large group by observing the cooks she employed. Her own baking was legendary, and soon there were often more guests than loggers. The family added another wing and outbuildings, and Annie supervised the kitchen, purchased supplies, and kept the books for the “hotel that was developing spontaneously.”27 Edward's attempt to manage logging camp affairs fared no better than his mail or tea businesses. His next step was to expand Annie's boardinghouse into the family-run Bay View Hotel.28 Kitsap County commissioners granted his petition for a saloon and a liquor license, and Edward later added ninepins and billiards as attractions.29

As saloonkeeper and proprietor of the Bay View, Edward Clayson fought with mill administrators and with the commissioners. He described Seabeck as a “penal colony” and cast himself as the “only free man” living in “free territory” across the inlet from the mill.30 He was embroiled in a conflict about a bridge that connected his property with the town, and ultimately the mill company, which owned the land, had the bridge destroyed.31 The first mill officials and many early residents were from Maine and supported the prohibition of alcohol; they controlled town policies until 1869, when public pressure from workers and proprietors to grant liquor licenses won the day. Even though prohibition in Seabeck ended before Edward Clayson began the Bay View enterprise, elements of the alcohol conflict peppered his relationship with the town and mill thereafter.32 Clayson also worked to prove that the Washington Mill Company and other Kitsap County firms had cut timber illegally on lands in the public domain, and to expose the graft that went along with the practice. All of this fostered what Esther later characterized as a “man against monopoly” political philosophy that led Clayson to embrace the Populist Party, Dennis Kearney's Workingmen's Party, Henry George's “single tax,” and eventually Theodore Roosevelt's Progressive Party. “Petty personal immorality, like petty larceny, didn't matter much” to him, Esther recalled later. “But grand immorality, corporate transgression, the circumvention of the law, and the exploitation of the Public Domain and of working men should be put down with a strong hand.”33

Edward viewed his short-lived newspaper, the Rebel Battery, published in 1878, as another weapon in his war with the mill. He shot rhetorical barrages at mill administrators and represented the virtues of the Bay View Hotel as a thorn in their side. “The hotel is located just outside of the borders of the Kingdom,” he wrote. “It is the first respectable hotel ever built in Seabeck,” and “the money you spend in this hotel does not help, either directly or indirectly, to swell the funds of the…powerful monopoly [of the mill.]” The Clayson family was “numerous enough to run the whole concern from the concert room to the hotel buildings to digging out stumps on the farm.” He advertised good food, convivial surroundings, a flowing bar, music, and a “splendid Base Ball Ground.”34

In the pages of the Rebel Battery Edward Clayson invited mill workers to “find aid and comfort at the Bay View Hotel,” meaning “free meals, drinks, and cigars.” Annie called them “guests of honor” with great irony, and was angry and frustrated as they siphoned off any profits the Bay View might make. Esther and her brothers considered them “bilks” who “didn't care a hang about injustice to labor or the devastation of the national forest. For want of a better hearing, Father read his writings to them, and they had to listen and applaud or go hungry.” Mill administrators branded the Claysons “outsiders, trouble makers, disturbers of the peace,” and mill workers risked their jobs if they patronized the Claysons' establishment. Annie tried to be a peacemaker and broker between her husband and their neighbors, the mill administrators, and the legitimate patrons of the Bay View. Given the circumstances, it was a challenge at best, and the Clayson children negotiated their way through childhood in the middle of it all.35

As a young girl, Esther considered her family's Seabeck logging camp “a glorious playground” beyond compare. She later remembered a parade of “bullwhackers, fallers, buckers, barkers…greasers to grease the skids of the road, and hook-tenders to tend the iron hooks and chains used in getting the logs out of the woods.” Bullwhackers were the “mighty men who thought nothing of giving a boy or a tomboy two bits, and sometimes four bits, on pay days,” she recalled. “These small coins were called ‘chicken feed’ by the best men in our crew, and as little chickens we never lacked for pocket money while the loggers had any to give.”36 Esther, tagged “Daredevil Dick” by her father, won the right to follow along with her older brothers on fishing expeditions by catching the bait; they all explored the woods and shipwrecks and invented games of adventure. Sometimes, to the great scandal of Seabeck, they danced naked in the shallow water separating their home and camp from the town. It was ...