![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Water and Woods in Pennsylvania

Walking through the ancient hemlock grove in the bottom of a remote valley in Pennsylvania's Huntingdon County, hikers in the 1890s may have wondered why a patch of tall evergreens was still standing when nearly everything nearby had been cut down. This area in the south central part of the state is known as Seven Sisters, and by the end of the nineteenth century, each of the seven mountains from which its name derives had been sheared of trees. Only the valley floor remained green. Perhaps a property dispute between two lumber companies saved these few majestic acres. Or maybe the company that was cutting in the area went bankrupt before the final trees were down. No one seems to know for sure.1

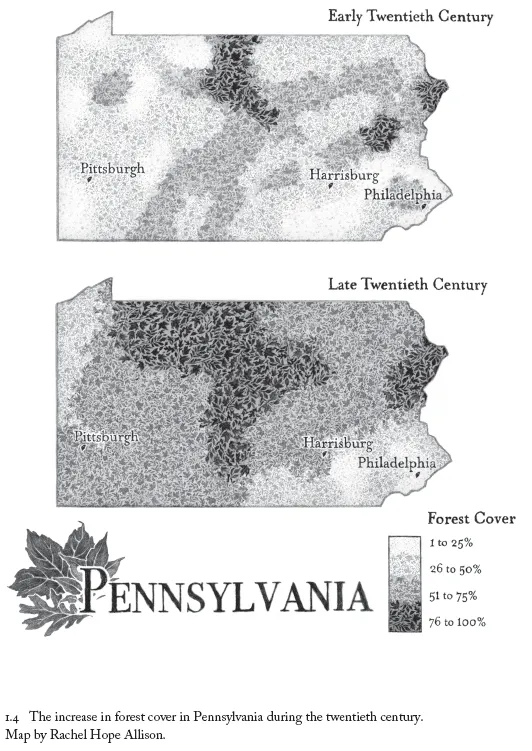

While the hemlocks remain an unexplained anomaly and the most regal living things in sight, they no longer gaze on naked hills. They are surrounded by thousands of acres of hundred-year-old red oak, yellow birch, black birch, ash, cucumber magnolia, striped maple, sugar maple, basswood, tulip trees, sycamore, and rhododendron. The five-hundred-year-old hemlocks are ensconced in a rambling, messy, and beautiful eighty-thousand-acre state forest, a lush landscape of old trees that appears timeless, endless, and wild.2

It seems inevitable, this treed land. These mountainsides and riverbanks have always welcomed woods. Even when loggers cut with abandon, trees grew back easily and quickly. In areas where Pennsylvania's agricultural and mining industries were at their height in the early nineteenth century, saplings threatened to fill in fields and take back mill sites if vigilance lagged. It was constant work to fight back the forest. But by the end of the nineteenth century, it seemed as though this marvelously resilient landscape was nevertheless doomed. Too much had been cut too fast, and too thoroughly, for too long.

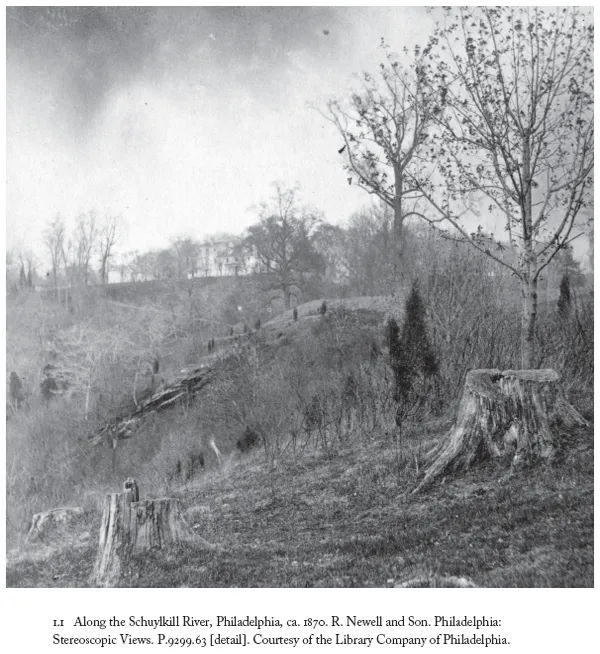

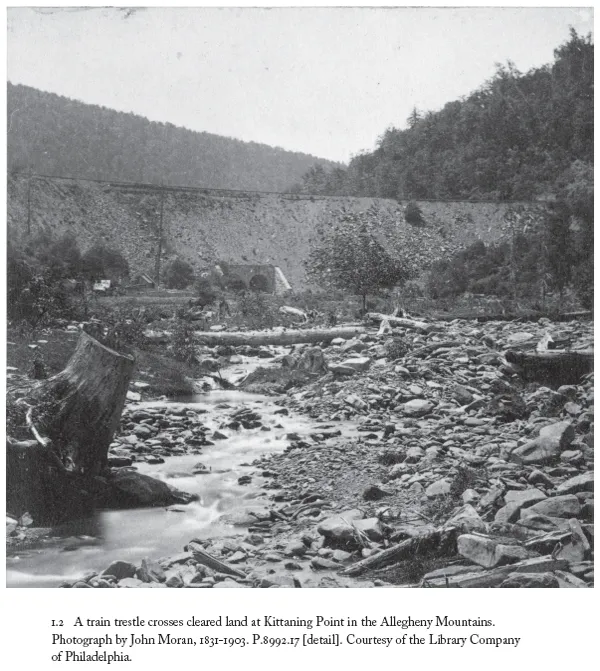

Ever since the early years of European settlement, farmers in Pennsylvania and throughout the Northeast had aggressively cleared forests to make way for fields. Even as the twentieth century dawned, property owners continued to harvest trees at a rapid rate, encouraged to clear as much land as possible by tax policies and lucrative markets for lumber and fuel. But as the state's cities grew and as scientists developed compelling theories about the role of forests in filtering water supplies and preventing both floods and drought, urban activists began to push for a more comprehensive understanding of the value of trees.

As we look back on nineteenth-century seedlings amidst tangles of vine, hindsight allows us to see a future of mature forests taking root in the ravaged landscape. We now know that the trees encroaching on recently abandoned farm, mining, and lumber land—if left alone—would become towering woodlands, a rich habitat for mammals, birds, insects, molds, flowers, fungi, and ferns. But the nineteenth-century hiker instead saw desolation, ruined industry, ill-managed land, and a threat of timber famine that would starve the region in more ways than one. Who would ensure that the land would, in fact, be left alone? The answer, it turns out, lay miles away, in the largest cities of the state.

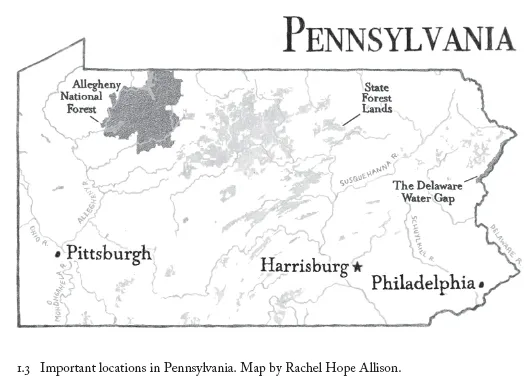

Those fears of timber famine, drought, and disappearing jobs were keenly felt in the state capital in Harrisburg, in the industrial sectors of Pittsburgh, and throughout the scientific community in Philadelphia. As those cities grew, their residents pushed their municipal governments, their state legislators, and eventually the national government to create new forests and put newly forested land under government protection to safeguard against future disaster.

The situation seemed dire. By the end of the nineteenth century, most of Pennsylvania's forests had been cleared for agriculture, mining, timber, and homes. Less than 40 percent of the state's territory could still be called “forest land,” and for most of that, the term was a stretch. Almost all of the land had been cut over at least once, and where trees were left standing, they were frequently pathetic, tiny specimens. In a state that had been named for forests and had once been virtually blanketed in trees, Penn's woods had almost vanished.

Pennsylvanians fretted their loss. By the 1890s, beating back wilderness in the service of civilization no longer seemed wise. People were coming to believe—if haltingly—that they were dependent on environments much more complex than had seemed possible before. A region without trees, they were learning, would be bereft not only of lumber, fuel, and the income of a timber industry but also of drinking water, reliable water power, and navigable rivers. Trees, scientists of the day warned the state's citizens, regulated and purified the water of the state's rivers and reservoirs. Trees captured rainfall in soil, allowing water to filter slowly to rivers and lakes; leaves sheltered snow from the sun and moderated the speed at which ice and wintry drifts could melt; and forests even meant more rain, since trees coaxed moisture from the air by bringing the temperature down. Without forests, rain would splash across the hillsides' surfaces and race to rivers the moment it fell from the sky, plaguing the state with floods in the spring and droughts in the summer. And another danger loomed: water quality. Without forests as filters, drinking water would become foul.3

In an address to the state legislature in 1896, Pennsylvania Governor Daniel H. Hastings described his fear of a treeless future. “This is perhaps the first generation in this Commonwealth that has been brought face to face with the dangers and disasters of a timberless country,” he told legislators. Even land classified as forest, he declared, “possesses almost nothing that is worthy of the name or would be valued by the lumberman for sale or by the mechanic for construction. Many of these large, unproductive tracts present a picture of desolation which cannot well be contemplated without awakening apprehension as to their future bearing on the prosperity of the Commonwealth.” These sorry and desolate “woodlands,” if not restored, would mean the loss of both timber income and lumber supply for the state.4

But the governor was most concerned about implications for the state's water supply. “It is recognized as a fact that of the waters which fall upon cleared areas, four-fifths are lost because they run immediately out of the country; while four-fifths of the waters which fall upon our forested areas are saved,” he warned, quoting with confidence the newest understandings of how forests held water in the soil. “It is now submitted to the General Assembly that it would be both wise and profitable for the State, in some right manner, to become the owner of these vast and comparatively worthless forest areas which contain the source of our water supplies, and to hold them as such reservations, protecting them from forest fires and encouraging regrowth of forest timber.”5 It was a long struggle to get such lands under protection, and one that Hastings would not live to see fully realized, but his vision is now tangible in the 2.5 million acres of state and federally owned forests flourishing in Pennsylvania today. Many acres beyond that number are also in trees—privately held forests that state policy has both nurtured and protected.

Pennsylvania was the home of the nation's first professional forester; the site of the first state-run forest academy; an incubator of new scientific thought about the relationships between cities and trees; and ultimately a laboratory where ideas about taxes, forest management, urban beautification, and water supply were developed in ways that were later incorporated into land management policy throughout the nation. Pennsylvania—with its confusion of municipal structures (so different from the orderly townships of New England) and its unusual proliferation of large cities and towns (from Philadelphia to Scranton to Harrisburg to Pittsburgh and dozens of smaller places in between), combined with elite Philadelphians' sense of themselves as the leaders of the young republic's scientific community—was at the vanguard of managing wildlands and cities as part of one single, interdependent landscape.

That single landscape was clear to nineteenth-century observers like Governor Hastings and his contemporaries. Gifford Pinchot, who grew up in Milford, Pennsylvania, and whom Theodore Roosevelt appointed as the nation's first chief of the U.S. Forest Service in 1905, considered the connections between cities and distant landscapes to be self-evident. Joseph T. Rothrock, who took charge of the state's forests in 1893, saw safeguarding cities and towns as his primary job. Mira Dock, a botanist and city-beautiful activist from Harrisburg, who joined the state's Forestry Commission in 1901, had always connected the health of cities and their residents to the health and proliferation of trees.

Dependence on the natural world was much more tangible in a time when water was not available at the kitchen sink, and when sewage did not somehow magically disappear down drains or with the flush of a toilet. At the end of the eighteenth century, Philadelphia had just over 40,000 residents and—like every other city in the young country—no central water supply. People drew their water from private wells—often in a backyard, not far from the outhouse—or from local pumps. While scientists had not yet taken hold of germ theory to explain the spread of illness, most people associated foul-tasting water with disease. When a yellow fever epidemic swept the city in 1793 and again in 1798, city leaders came under serious pressure to make drinking water safe.6

In 1801, Philadelphia was both the largest American city and the first to build a municipal water supply system. Designed by engineer Benjamin Henry Latrobe, the system involved steam pumps at an intake station on the Schuylkill River to the city's west. The pumps brought water high enough out of the river to flow by gravity through wooden pipes to an elaborate building at Centre Square, where Philadelphia City Hall now stands. Inside the neoclassical building, another set of steam pumps pushed the water up to two water tanks enclosed in the top of the building. All Philadelphians able to pay a fee and build a connection to the main distribution pipes constructed throughout the city could have access to this river water from outside the built-up area, water that was believed to be more pure than any available from local wells.7

Despite being the newest and best thing at the time and a major sightseeing destination for visitors, within fifteen years the capacity and technology of the Centre Street Station were no longer sufficient. Latrobe's former assistant, Frederick Graff, designed and oversaw the construction of a complex of pumping stations on the east bank of the Schuylkill, along with a series of reservoirs atop the hill where the Philadelphia Art Museum now stands. That technology served the city for almost a century. The sophisticated waterworks were also beautifully landscaped, and both picnickers and engineers made the place a popular destination. By the mid-nineteenth century, over a hundred American cities had followed Philadelphia's example of providing water to their residents through municipal systems.8

As Philadelphians soon learned, however, providing centralized water and providing safe water, though connected, were not synonymous. As the city continued to grow, more sewage and other pollution from mills, factories, and homes entered the rivers upstream from Philadelphia faucets. In an effort to limit the pollution traveling from riverbanks to households, the Philadelphia city government began purchasing land along the Schuylkill River in 1843. In 1855, the city council formally named and dedicated the riverbank purchase areas as Fairmount Park, thereby establishing what would become one of the largest municipal parks in the country, encompassing 10 percent of the city's land. New York City's Central Park is a mere 843 acres; today, Fairmount Park totals over 9,000.9

The ideas behind the land purchases and the establishment of the park were simple and straightforward, and yet novel for their time. If there were no factories on the riverbanks, there would be no factory effluent to poison the water. If there were no homes lining the rivers, no household sewage would threaten the city's health. There was as yet little thought of trees or of forested upland watersheds being central to the safeguarding of water supplies; those ideas would be popularized later, most famously through the writings of George Perkins Marsh. At first, it was lack of development rather than presence of trees that caught the public imagination and seemed to promise water purity and public health.10

Because Philadelphia began early with water supply technology, it found itself on a path of technological dependence that meant its engineers and planners ultimately failed in what Boston and New York City were able to accomplish by beginning later, after the mistakes in Philadelphia were more fully understood. Those cities were able to protect their water supplies by controlling upriver land. Today, both Boston and New York City are able to offer their residents unfiltered drinking water because the forested lands surrounding their upstate reservoirs are protected and regulated to such an extent that chemical treatment alone is sufficient to ensure the water's safety. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency closely monitors the water quality in those unfiltered reservoirs, and both cities one day soon may be forced to build filtration plants.11

Philadelphia, always on the cutting edge of water supply technology, began filtering all of its water in 1911, after failing to gain sufficient control over its upriver lands.12 In failure, there was a different kind of success. Other municipalities looked to Philadelphia's experience, and thousands of acres of the state's lands were placed under protection in ways that would allow forests to return over the next century. Pennsylvanians changed the way that people in the region—urban residents, foresters, botanists, farmers, vacationers, and others—thought about the connections among cities, water, and trees. Though Philadelphia moved characteristically quickly to adopt a “modern” technological solution that would later look like giving up the good fight, the lessons learned there pointed toward more regional and ecological approaches to both land management and water supply security.

What had been modern in 1801 had become imperiled by the end of the century, prompting Governor Hastings's dire warnings of a treeless and parched future for the state. But it is precisely that century of striving to protect the Philadelphia water supply that brings us to Pennsylvania for the origins of the return of northeastern trees. Philadelphia was the nation's center of science, and it was in Philadelphia that the most dramatic advances were made in both water supply technology and understanding forests. Unfortunately, the strides made in the two fields were out of sync, and it was left to other large cities to build on what Philadelphia had learned. Because of advances made in Pennsylvania, New York and Boston were able to build their water supply systems with a clearer understanding of the role that forests could play.

The hydrology of forests, the technology of water supplies, the biology of particular trees—these were all new and exciting fields of inquiry in the nineteenth century, pursued by men of science (and a handful of women) who were not trouble...