![]()

CHAPTER 1

RANKING “KOREAN” PROPERTIES

Heritage Administration, South Gate, and Salvaging Buried Remains

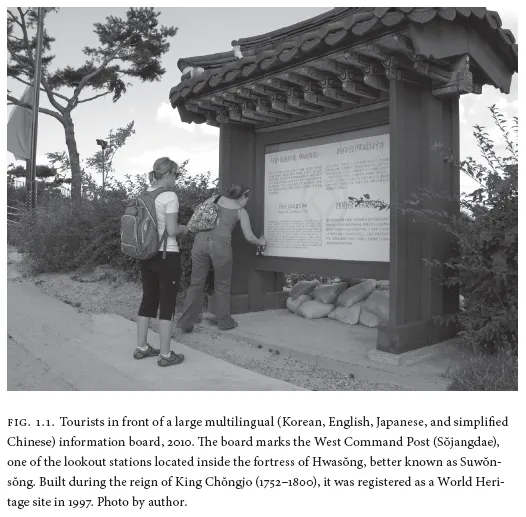

The Cultural Heritage Administration, or the Munhwajae Ch'ŏng (hereafter CHA, 1998–present), formerly the Office of Cultural Properties (Munhwajae Kwalliguk, hereafter KSMKG, 1961–98), has played the major role in transforming the cultural and tourist landscape of the Republic of Korea. For more than three decades, its committee members and staff have worked hand in hand with the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism (MCST; Munhwa Ch'eyuk Kwan'gwangbu) and the Korean Tourism Organization (KTO; Han'guk Kwan'gwang Kongsa) to promote Korea to a world audience. Beginning with the successful staging of the Seoul 1988 Olympics, these national institutions have constructed museums, monuments, and shrines, as well as erected tens of thousands of signs and markers promoting cultural properties throughout the peninsula.1 They have also deployed media outlets, including newsletters, newspapers, television, and the Internet, to advertise Korea's latest World Heritages sites—royal palaces, tombs, temples, Yangban Villages architecture, and ancient walled towns such as Suwŏn (fig. 1.1) and Kyŏngju (see figs. 5.5, 5.6, 5.7, 6.5, and 6.7)—to both the domestic audience as well as foreign visitors (KS Korean National Commission for UNESCO 2001, 2002). Consequently, from the densely populated urban enclaves of Seoul to remote mountainous locations only hikers frequent, one can come across green-painted railings fencing off state-designated cultural properties and heritage zones. As we can see in figure 1.1, heritage sites are demarcated by “Korean-style” columns decorated with red-stained gabled roofs framing large, shiny metal plaques inscribed with the name of the monument and its registered classification or ranking category as a world heritage site, national treasure, treasure, historical site, natural monument, or provincial-government-designated property. In recent years, in an attempt to greet all visitors, these information boards and tourist maps have been translated into English, Japanese, and, increasingly, simplified Chinese.

Because of the perceived inherent value of cultural properties as immutable tangible relics demonstrating Korea's antiquity, ancestral achievements, and the unbroken continuity of its civilization, more than in any other country, state-employed archaeologists, architects, curators, academics, and research staff in Korea have micromanaged every aspect of heritage management (including excavations, collections, documentations, registrations, museum exhibitions, and restoration projects) for tourists in the past century. Although in 2011 the CHA commemorated its fiftieth anniversary as the supreme arbiter of state-directed cultural initiatives, very few (except for a handful of historians and insiders working for the CHA) are aware that the institutional foundations of Korea's cultural heritage management system dates back much earlier, to the early colonial period in the 1910s (Pai 2001). Like many political, military, economic, and cultural institutions introduced by Japan's empire-building colonialists and administrators, the CHA inherited its hierarchical working structure and property-ranking criteria directly from the Government-General of Chōsen (Chōsen Sōtokufu, hereafter CST) Preservation Laws Governing Antiquities and Relics that were first promulgated in 1916, and, therefore, it is not without much controversy (Pai 1994, 2006). For example, the bulk of Korea's most representative national treasures (kukpo)—such as Pulguksa Temple (see figs. 5.6 and 5.7), Sŏkkuram Grotto (see figs. 5.5 and 6.5), and archaeological remains dating back to the Three Kingdoms era (c. 3rd–8th century CE)—were first surveyed, excavated, and reconstructed for tourists by Japanese scholars, engineers, and developers (Pai 1994, 2010a, 2010b, 2011). Therefore, the CHA's naming and ranking systems for Korea's national treasures inventory have sometimes been challenged as relics of colonial practices that have distorted the “true” identity, age, and artistic worth of Korea's core body of ruins and relics.

Since the first Cultural Properties Preservation Act (Munhwajae Pohobŏp) was promulgated in 1962, the term “state-designated heritage” (chijŏng munhwajae) has been broadly defined as consisting of natural and man-made objects designated as having important archaeological, prehistorical, historical, literary, artistic, and technological importance. The CHA Ministry, currently ranks national cultural properties into the following seven categories:2

1. National treasures (kukpo): Heritage of a rare and significant value in terms of human culture with an equivalent to “treasures.”

2. Treasures (pomul): Tangible Cultural heritage (yuhyŏng munhwajae) of important value, such as historic architecture, ancient books and documents, paintings, sculpture, handicrafts, archaeological materials, and armory.

3. Historic sites (sajŏk): Places and facilities of great historic and academic value that are worthy of commemoration (e.g., prehistoric settlements, fortresses, ancient tombs, kiln sites, dolmens, temple sites, and shell mounds).

4. Scenic places (myŏngsŭng): Places of natural beauty with great historic, artistic, or scenic values, which feature distinctive uniqueness and rarity originated from their formation process.

5. Natural monuments (ch'ŏnyŏn kinyŏmmul): Animals, plants, minerals, caves, geological features, biological products, and special natural phenomena carrying great historic, cultural, scientific, aesthetic, or academic values, through which the history of a nation or the secrets of the creation of the earth can be identified or revealed.

6. Important intangible cultural heritage (muhyŏng munhwajae): Drama, music, dance, and craftsmanship carrying great historic, artistic, or academic values. The list includes the following: (a) living artisans who, as “possessors of traditional arts and crafts” (poyuja), are represented by craftsmen, wine makers, singers, and musicians; (b) religious customs such as Confucian ancestor ceremonies and shaman exorcism rituals; (c) regional theaters and musical and village dances; and (d) folksongs and folktales.

7. Important folklore materials (chungyo minsok charyo): Clothing, implements, and houses used for daily life and business, transportation, communication, entertainment and social life, and religious or annual events that are valuable for understanding people's lifestyles and more. This category includes subsistence strategies such as food-preparation techniques, cooking recipes, local agricultural festivals, rituals (sixtieth birthday party, ancestral worship, and shaman rituals), local customs, games (kites, wrestling, and the like), religious customs (shaman paintings), and costumes.

The application forms submitted for formal consideration must include detailed information such as the name and address of the owner of the property where the artifact was reported, its location, its discoverer, its measurements, legends, related stories, and the state of preservation—all of which are recorded side by side with an attached photograph. The registration requiring specialists' survey records, supporting historical records, and collections of associated legends supervised by CHA staff is a complex and time-consuming bureaucratic process. Once an item is deemed worthy of serious investigation, one of the CHA committee members is dispatched to the site to verify its status and report it to their respective committees. Currently, CHA-appointed specialists (munhwajae wiwŏn) meet monthly, as nine separate committees (punkwa wiwŏnhoe): (1) Architectural Heritage; (2) Movable Cultural Properties Division; (3) Historic Sites and Monuments; (4) Historic Cities Division; (5) Archaeological Heritage; (6) Natural Heritage; (7) Intangible Cultural Properties; (8) Modern Cultural Heritage; and (9) Heritage Security. The final decision to register a cultural property is handed down by the minister of CHA, who awards a certificate of authenticity (munhwajae taejang). In addition, on occasion the committees will decide which state-designated inventories (munhwajae mongnok) are to be reshuffled between categories, appended, or delisted, depending on reports of new discoveries and major restorations, either due to natural or man-made disasters in the previous year.3 The class and ranking of a cultural property is particularly significant, because it determines not only the amount of government funding granted for its preservation, study, and promotion but also its monetary value in the international art market.4 The fact that the 2010 budget for the CHA amounted to 521.2 billion Korean won (about 500 million dollars) indicates how much the government invests in long-term efforts to preserve and promote for posterity the tangible symbols of Korea's natural and cultural identity.

According to the CHA search engine, as of 2011 the number of nationally registered cultural properties totaled 3,385 items (see appendix, table 1), including a wide array of both tangible and intangible properties from prehistoric sites, such as shell mounds and rock reliefs; burial goods of bronze weapons and gold crowns; architecture such as Buddhist cave temple sculptures; tumuli, Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1910) royal burials, and shrines; palaces, battle sites and fortresses; natural monuments (plants, trees, animals, and mountains); and skilled artists and craftsmen designated as “living treasures” or “possessors of tradition” (poyuja). Once a site is registered, it is the duty of the CHA to inform the general public of the status of the ever-growing list of national treasures, historical sites, and folk resources. Although previously the bulk of heritage information was disseminated in school textbooks, published catalogues, and national or municipal government-issued monthly newsletters, today anyone can visit the CHA home page to access the latest news and statistics of discoveries, excavations, and restoration projects, as well as tourist information about transportation access and a wide array of visitors' facilities (see appendix, table 2). The recent addition of an English-language search function indicates that cultural properties are being valued as increasingly vital components in “branding” the cultured image of the country for a world audience. In recent years, the CHA has also actively courted “netizens” input by sponsoring online competitions with a sizable amount of prize money (US $1,000–3, 000) awarded for the best essays, tourist photos, posters, videos, and even academic papers addressing new ways to promote heritage venues to tourists, including festivals and cultural events held at royal palaces, temples, historical sites, and ancient capitals such as Kyŏngju and Puyŏ (see fig. 1.6).5

In contrast to such outreach efforts, CHA committee membership has historically been reserved for well-connected academics who have served at least ten years as professors at leading universities, or for curatorial staff at national museums. Over the decades, CHA-appointed experts have expanded to include a wide range of disciplines, including archaeology, anthropology, art history, architecture, ancient history, ethnomusicology, ethnology, botany, zoology, and geology. That is, their expertise has qualified them to evaluate which geological formations, natural species, objects, monuments, talents, and skills should represent the body of “Korean” identity and heritage. Most notably, out of the hundreds of academics who have served as committee members over the past five decades, the most prestigious posts (such as the directorships of the network of eleven national museums) have been dominated by archaeologists and art historians who were appointed as the “authentic” speakers of Korea's most ancient past. For example, the first director of the National Museum of Korea was Kim Chae-wŏn (directorship, 1945–70), an art historian and archaeologist who received his degree from the University of Munich (Kim Chae-wŏn 1992).

He was succeeded by Kim Wŏl-lyong (r. 1970–71), another art historian and archaeologist, trained at Seoul National University, with graduate degrees from New York University and the University College London. Kim Wŏl-lyong is also often referred to as the father of native Korean archaeology because he founded the Department of Art and Archaeology at Seoul National University (Kogo Misul Sahakwa). Kim was the influential author of Introduction to Korean Archaeology (Han'guk kogohak kaesŏl), which has been published in a dozen revised versions and has served as the bible for students of Korean archaeology since its first edition appeared in 1973 (Kim Wŏl-lyong 1986). The third director, Hwang Su-yŏng (1972–74), was also an art historian, with degrees from Tokyo University, and is recognized as the preeminent expert on the Buddhist art and sculpture of the Three Kingdoms period (Hwang 1989).

The fourth director of the CHA was Yi Kŏn-mu (2008–11), another Seoul National University–trained archaeologist of prehisty who earned his pedigree excavating under his mentor, Kim Wŏl-lyong. Yi's other positions included the directorship of the Kwangju National Museum and of the National Museum of Korea.6 In 2011, he was replaced by Ch'oe Kwang-sik (2011–12), another scholar of ancient history and former director of the Korea University Museum. As we can see, over the past fifty years, a small core of state-appointed bureaucrats and academics trained at elite universities have exerted enormous influence in defining what, who, and in which order something or someone represents the ever-growing body of “Korean patrimony.”

The current structure and ranking system of the CHA bureaucracy can be traced back to the year 1961, when its predecessor, the Office of Cultural Properties (Korea [South] Munhwajae Kwalliguk; hereafter KSMKG) was founded under the auspices of the Ministry of Education. The OCP's official journal, Journal of the Office of Cultural Properties (Munhwajae), was launched in 1965 and is still published today. The following mission statement in the journal's inaugural issue states the raison d'être of the KSMKG as follows:

The goal of the office and its promulgation of cultural preservations laws and regulations is to preserve, manage, and reconstruct our cultural properties so as to hold on to our most precious ancestral heritage and keep them with us for eternity…. Furthermore, we have to make up for the systematic destruction and plunder of Korean art and architecture perpetrated by the Japanese. Our mission is also an urgent one because Korea's cultural properties are currently being threatened daily by the onslaught of Western culture with the stationing of American soldiers in the postwar period. (KSMKG Munhwajae 1965b, 1–6)

The patriotic sentiments expressed in this directive clearly reflect the overwhelming pride of ownership of museum officials, curators, and KSMKG committee members, who have often referred to themselves as “the creators of Korean Culture” (minjok munhwa ch'angjo; KSMKG 1965b, 1). The amorphous slogan dubbed the “Korean spirit” (Chosŏn chŏngsin) was the most-often-cited criteria considered by the committees when deciding which objects, historical sites, and monuments ought to represent Korea's racial identity and cultural lineage (Pai 2001, 76).

Needless to say, the patriotic direction of the KSMKG's policy mandates during the 1960s through the 1980s was also heavily influenced by the personal ambitions of past presidents, who ruled with an iron fist for more than three decades. President Park Chung-hee (r. 1961–79)—a former colonel in the Japanese army who masterminded a coup in 1961 following the chaos of the student revolt that overthrew the lame-duck President Syngman Rhee (1875–1965)—is widely acknowledged as the first president to use “history” as a political tool in a systematic manner (Park S. 2010; Park Sang-mi 2010). According to the broad outlines of Park's 1972 Yusin Constitution's ideology of national restoration that was propagated in school textbooks and the media, the trajectory of Korea's history was driven by the spirit of national resistance (t'uchaengsa) in order to preserve the Korean people and its unique culture from invading foreign armies. In this overarching narrative, Korea's unique identity and independent spirit were forged over two millennia, in resistance to successive invasions by Chinese conquerors, beginning with Han Emperor Wu-di (c. 108 BCE) and continuing with the dynasties of the Sui and Tang (6th–7th century), the Mongols (13th century), the Khitans (17th century), the Japanese (16th–20th century), the Manchus (17th century), the US Army (1945–48), and, finally, the communist North during the Korean War (1950–53) (Kal 2008). The turning points in the struggle for national independence were not only marked by epic battles but also by the appearance of self-sacrificing martyrs such as Admiral Yi Sun-sin (1545–98), who saved the people from the rampaging armies of Japanese warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–98) during the Imjin Wars (1592–98). Handpicked as Korea's hero par excellence Admiral Yi under President Park's directive, the KSMKG commissioned the construction of several war monuments to consecrate the bitter memories of the seven-year period of the Imjin War, including the Hyŏnch'ungsa Shrine (1966–75) and a floating replica of Yi's “turtle boat” in white stucco placed in an inlet of Hansando Island, where Yi famously defeated the Japanese navy (Korea [South] Munhwa Kongbobu 1979, 288–89). Today, reproductions of turtle boats are ubiquitous; they appear as artwork etched into wall reliefs adorning the halls of the Yongsan National War Memorial, as well as in many lesser-known war memorials scattered throughout the peninsula (Jager 1999). They are also sold in souvenir shops in the form of miniaturized toys, drawings, and puzzles (Park Yŏng-mu 1971). The most famous relic dating from Park's Yusin era is the colossal bronze statue of the admiral that still towers over the renovated Kwanghwamun Plaza (fig. 1.2), which has now been transformed into a family-friendly destination complete with fountain...