![]()

PART I

SHANGRILAZATION

Tourism, Landscape, Identity

These old men [two seventy-five-year-olds in Hamugu Village] started hunting before Liberation because their families were poor—their living conditions were difficult, so they took up hunting. They hunted mostly musk deer and bears because of their high value, and this allowed them to make a go of it. At the age of sixty they stopped hunting. Now they regret having done it. Over the years their families and their livestock have suffered misfortunes of various kinds. Divinations at the monastery show that they’ve been punished for not respecting the zhidak [territorial gods commonly abiding within mountains] and sacred lakes. . . . [In similar fashion] government-organized timber-felling destroyed thousands of ancient trees—a serious misfortune. We now protect the forests and I am very happy; not destroying the sacred mountains and lakes is excellent. We Tibetans [believe] that wild animals living in the realm of the deity mountain have relationships with the zhidak, the ecology, the local people, and nature that is like the relationship between you and me. All are living beings. Conflicts between animals and people are like conflicts between people; if you violate someone they will take action against you. . . . The cable car system that is being built on the [primary local god] mountain is already having severe environmental impacts, and when droves of tourists ride up to the summit there will be destruction that takes forms not immediately visible to the eye. Already there are mudslides occurring in several nearby villages and the destruction is bound to increase. Only by protecting the ecology, the zhidak, and the sacred lakes can there be peace, and only after there is peace can there be prosperity.

—LAZONG RUIBA

WHEN Lazong Ruiba, an environmental activist from Hamugu Village, made these observations in 2005, Zhongdian County was still adjusting to its new life as “Shangrila.” In 2001, China’s State Council announced the “discovery of Shangrila” in an economically marginal region of southwest China internationally recognized for its high levels of biological and cultural diversity and its spectacular mountain scenery. On May 2, 2002, after a battle among neighboring provinces and prefectures lasting more than five years, Zhongdian County was officially renamed Shangrila (Ch. Xianggelila). Zhongdian’s accession to Shangrila status occurred after a search party of more than forty scholars from Yunnan and other provinces “proved” that the setting for James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon (the source of the name) was based on descriptions of the Zhongdian basin in the writings of the early twentieth-century botanist and explorer Joseph Rock. Becoming the star attraction of the Greater Shangrila Ecological Tourism Zone, a region that includes the Sino-Tibetan border areas in Yunnan, Sichuan, and Qinghai, as well as the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), accelerated the transformation of the county into “a world tourism brand name” and global tourism hotspot and helped accelerate the development of tourism and other forms of commerce throughout the region.1 A brief consideration of the shangrilazation process in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture sheds light on how tourism development schemes shaped many towns and cities in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands in the late 1990s and early in the first decade of the 2000s.

In Diqing, a decade of explosive growth in the tourism industry has also seen the rapid extension of the transportation network and the transformation of urban and small-town landscapes. In 1999, when ground transport to Kunming, the provincial capital, was still limited to dirt roads, the Diqing airport was built among farmhouses and pastures just outside the Shangrila county seat, Zhongxin Town (known by Tibetans as Gyalthang, which is the source of another Chinese name for the town, Jiantang). Sections of the paved highway from Kunming were still under construction in 2004, but enhanced transport links arose in tandem with the architectural re-creation of a Tibetan sense of place in the town itself:

Whereas in 1998 the town . . . was unassuming, dominated by the usual grey and unimaginative concrete blocks that could be seen in any Chinese town, in 2002, this was no longer the case. By then all the buildings lining the main street were being repainted with bright colors in “Tibetan” designs, described by one visiting journalist as the creation of a “Tibetan toy town.” Following this, elaborately decorated streetlamps were put up, and the sidewalks were repaved with stones. . . . Although the traffic in Zhongxin Town was still easy to navigate, the first traffic light appeared in 2003, while new hotels were emerging all over the town. In the Old Town of Zhongxin, Dokar Dzong [Dukezong], things were also happening. The streets were still squalid, as in the rest of the town’s back streets, but this area was gradually developing a reputation as a backpacker zone with quaint little guesthouses and cafes opening up. (Kolås 2008, 4)

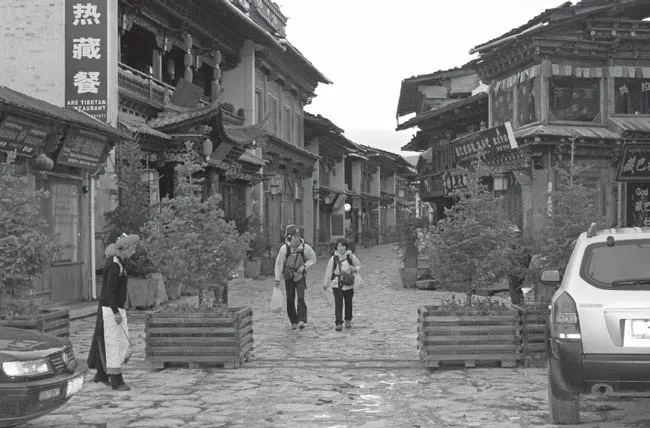

FIGURE I.1Young Chinese tourists exiting the maze of cobblestone streets and “Tibetan” shops, hostels, and restaurants that made up Dokar Dzong in 2011. Roughly two-thirds of Dokar Dzong was destroyed by a fire in January 2014. Photo by Chris Coggins.

By 2004, there were several five-star hotels in and around Zhongxin, and even the “squalid,” muddy streets that laced the Old Town, Dokar Dzong, were being carefully paved with cobbles, while more and more cafés, Tibetan souvenir shops, tea shops, guesthouses, and outdoor-gear stores sprang up all around. By 2005, the Old Town was the showcase of Shangrila—a simulacrum of a medieval Tibetan town—where cars were not allowed to penetrate into the winding, narrow lanes, and tourists, both Chinese and foreign, mingled with Tibetans before heading off on overland adventures into the wilds of rural Diqing, western Sichuan, or the TAR (fig. I.1). Each night, hundreds of local Tibetans and some adventurous travelers gathered in the newly rebuilt Culture Square to participate in folk dancing, moving clockwise in large, concentric circles in the fashion of a prayer wheel.

A critical reading of the restoration of Dokar Dzong could easily relegate the place to the likes of a Disneyfied Tibetan tourist trap (Llamas and Belk 2011), but that would require a static conception of the landscape, one that elides the involvement and agency of local people in making and remaking the Old Town to suit their own desires, interests, and values (Hillman 2010). An eye obsessed with signs of the ersatz is blind to the ways that Tibetan carpenters and woodcarvers hew the timbers, raise and fit the beams, and sculpt and paint the facades of the new stores using old techniques refined over generations of building farmhouses, shrine rooms, and temples across the region. Likewise, the work of Tibetan bureaucrats, entrepreneurs, academics, and others who are proud to promote “Shangrila” remains invisible or only dimly considered.

Perhaps more significantly, the invisible features of the landscape—attributes alluded to by Lazong Ruiba—become undecipherable, obscured by assumptions about the imposition of a new state-capitalist utopian order.2 For the purposes at hand, it should be kept in mind that while landscapes appear to be solid, natural, and in a sense incontrovertibly “real,” they are also both the products of visible and invisible sociocultural contests and the media through which form and meaning are continually instantiated. Furthermore, the practices that imbue a landscape with meaning and with a capacity for certain kinds of agency are not translatable without attention to the subject positions of those who live and work within them. We can conceptualize landscape as a quasi-object—a thing that humans act upon but that also has a certain degree of agency—with the capacity to structure social reality to a significant degree:

[Landscape] represents to us our relationships to the land and to social formations. But it does so in an obfuscatory way. Apart from knowing the struggles that went into its making (along with the struggles to which it gives rise), one cannot know a landscape except at some ideal level, which has the effect of reproducing, rather than analyzing or challenging the relations of power that work to mask its function. (Mitchell 1996, 33)

Both conventional historical accounts and more critical analyses of economic development often place Shangrila within a telos in which a region deemed by the state as a “backward minority minzu” area, brutally restructured into communes, work brigades, and Maoist study groups for decades, is now being transfigured. Sanguine observers see empowerment, or at least its gradual emergence, while critics see a utopian diorama—a simulacrum of “Tibet”—and a remarkable exemplification of governmentality meant to produce a multiethnic and economically vibrant Chinese hinterland.3 Politically astute and theoretically trenchant as such critiques may be, they miss the complex sociology of associations involving local and nonlocal actors in particular landscapes as both agentive subjects and objects of representation.4 Border landscapes are constituted by associations of nature, culture, and capital that are constantly reworked in the production of multiple Shangrilas. The chapters in part 1 focus on several modalities of the shangrilazation process: literary representations of the landscape in fiction and nonfiction; the representation of Tibetan landscapes and cultures in official travel guides and in the act of travel itself; and travel, photography, and writing as means of representing embodied experiences of discovery that both map “new territory” and establish it within the common geography of the nation.

In chapter 1, Li-hua Ying addresses the contribution of literature to the shangrilazation of Sino-Tibetan border landscapes as well as the centrality of the borderlands for the construction of Han, Tibetan, and other ethnic identities. Contrasting and comparing the works of Wen Pulin, Fan Wen, Alai, Tashi Nyima, and Li Guiming, all of whom write about borderland areas of Sichuan and Yunnan, she shows how Han and Tibetan literary communities adopt different strategies to make distinctive claims on national identity, place, landscape, and nature. Ying focuses on the fluidity of identities in these ethnically complex areas but also on the ongoing dialectics of “insider” and “outsider” identities, showing how Sino-Tibetan border landscapes are represented as part of the constitution of self and other in what she calls the “vital margins.” While travel literature is a catalyst for tourism, playing a critical role in the cultural economy of shangrilazation, the “frontier poetics” of Tibetan writers working in Chinese are a vehicle for reconstituting that which has been destroyed or obliterated—a means of challenging or dismantling the shangrilazation process. Ying demonstrates how contemporary literary renderings of life in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands articulate with a national discourse that places the region at the heart of a collective quest for spiritual renewal. She also shows how literary groups such as the Khawa Karpo Culture Society call for a return to indigenous roots, and how the success of Tibetan writers such as Alai and Tashi Dawa challenge the notion of the metropolitan center versus the cultural margins; literary renaissance thus becomes a form of reterritorialization that may counter the forces of shangrilazation.

Chapter 2, by Chris Vasantkumar, examines shangrilazation through a critical reading of two government-supported travel texts that depict Xiahe (Tib. Labrang) and Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, in Gansu, as a touristic dreamworld of consumable Tibetan culture. Drawing on these texts as well as ethnographic observations, Vasantkumar highlights the complex politics at work in a place marketed as “little Tibet” but where local Han and Hui have long been important members of the community. He argues that Chinese domestic tourists’ engagement with the landscape draws more on notions of the miniature than on Western landscape genealogies, and that the elision of the ethnic makeup of the area has been key to its shangrilazation as a miniaturizing method. At the same time, the two texts demonstrate the ambivalent and polyvocal nature of official tourist meanings. Chinese scenic spots are not necessarily hegemonic; instead, they are always in the making.

The final chapter in this section, by Travis Klingberg, also explores Chinese tourism in a Tibetan borderland area through a study of the transformation of the Yading Nature Reserve in southwest Sichuan, which has gone from a remote, rugged, and biologically diverse region visited by only the most determined explorers to a major destination that attracts tens of thousands of tourists annually. Packaged as “the Last Shangrila” and incorporated into the Greater Shangrila Ecotourism Zone, Yading is represented as a “nature destination” where tourism and biological diversity are seamlessly complementary. Like Vasantkumar, Klingberg challenges interpretations of hegemonic official tourist landscapes by focusing on the productive and influential role tourists themselves have had in the production of these landscapes through embodied practices of seeing and discovery. As the discovery of Yading becomes a shared routine for increasing numbers of Chinese tourists, even photography serves as a means of incorporating shared experience, of knowing and producing an exotic place within the national territory. Tracing three sets of explorations of the region—by Joseph Rock, Yin Kaipu and Lü Linglong, and the growing numbers of Chinese tourists, Klingberg demonstrates how Yading has become part of the national imagination and a remaking of Chinese national geography through tourists’ inscribing and incorporating practices.

Each of these case studies reveals the power of inscription, travel, imagination, and embodied practice in the making of place, landscape, and identity in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands during the era of the Great Western Development strategy. Each author also raises questions, implicitly or explicitly, about the possibilities for a popular politics of the governed in a period of striking transformation (Chatterjee 2006). Where Han travel writers seek more authentic selves in the “vital margins,” Tibetan writers forge a “frontier poetics” of recovery. Where the miniaturization practice is constitutive of a culture of landscape consumption that incorporates marginal places into the national imaginary, such works of imagineering do not endure unchanged for long. These chapters show that the landscape simulacra of shangrilazation are built of the visible and the invisible, of the remembered as well as the embodied. Therein lie struggles that are too easily obscured by reductive assumptions based solely on “reading” the landscape as text, productive as such readings can be. Above all, the work of landscape production is never finished. Thus, shangrilazation as material transformation and immaterial meaning-making is never hegemonic or complete but always in the process of formation, as a particular civilizing project of the Great Western Development strategy in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands. There is always more to the mountain than meets the eye.

PART 1. SHANGRILAZATION

Epigraph: Lazong Ruiba, personal communication, Hamugu Village, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, 2005.

1In 2004, China Daily (2004, 1) trumpeted the term “world tourism brand name” with pride, and tourism statistics indicate that it is not mere hyperbole. Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture has been open for tourism only since 1992, but the number of tourists increased from 42,300 arrivals in 1995 to more than 1.28 million in 2002 (Kolås 2008). By 2008, from 3 million to 3.8 million tourists visited Shangrila County (Jenkins, 2009; People’s Daily 2008). The number of international tourists remains relatively small but continues to rise rapidly, with 80,000 in 2002 and between 300,000 and 400,000 in 2008 (Yunnan Tourism Bureau, personal communication, 2004; Jenkins 2009).

2This is not to dismiss the idea out of hand. Karan’s (1976) early and highly compelli...