![]()

1

THE BEAUTIFUL TREE

Truth is relative to culture, that what one people takes for good, beautiful, and true may be thought as the reverse by another.

—JAMES R. JACOB

IN THE KASHAYA POMO LANGUAGE, TANOAK IS CALLED CHISHKALE, which translates to “beautiful tree.”1 In his 1889 description of tanoak, the first botany professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Edward L. Greene, called tanoak “the most remarkable of all North American oaks” and listed it “among the most beautiful of Californian forest trees.”2 One booster of tanoak as a source of fine-grained wood claimed in 1891 that “[i]t is not generally known that this is one of the most beautiful of all the hardwoods of America or, for that matter, of any other country.”3 In his multivolume treatise The Silva on North America, Charles Sprague Sargent ranked it among “the most interesting inhabitants” of U.S. forests in 1895.4 He claimed that no other western North American oak tree surpassed “the best representatives of [tanoak] in massive beauty, in symmetry of outline, or in richness of color.” Sargent described how “in early spring the elongated tender shoots and unfolding leaves coated with bright hairs, appearing like masses of flowers against the dark background of foliage, light up the dark coniferous forests” where it often grows.5

One late nineteenth-century writer for a San Francisco newspaper compared old-growth tanoak groves in Mendocino County to Druidic temples because of their lofty branches and pleasing forms, a romantic reference to the lost sacred oak groves used in the ancient Celtic religion of the British Isles and Europe.6 George Sudworth, a nationally recognized tree authority who worked for the U.S. Forest Service for more than four decades, remarked in 1908: “Economically a tree of the greatest importance in Pacific forest, both for its valuable tanbark and for the promise it gives of furnishing good commercial timber in a region particularly lacking in hardwoods.”7 Yet despite high praise, most Americans remain unfamiliar with this common associate in the coast redwood forests of the United States.

Tanoak occurs in a monospecific genus, meaning only one species exists in its genus on the planet. The tree variety, Notholithocarpus densiflorus var. densiflorus, grows from southwestern Oregon through the California Coast Range to near Santa Barbara, with inland populations occurring through the Siskiyou Mountains and from the southern tip of the Cascade Range along the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada to Yosemite National Park.8 Much of its coastal distribution overlaps with that of coast redwood, but due to its greater tolerance of drought, tanoak extends farther inland. The shrub variety, N. densiflorus var. echinoides, occurs in “scattered locations in the Siskiyou region and the Sierra Nevada to Mariposa County.”9 This “dwarf form . . . is more common at higher elevations in the north-eastern range of the species, particularly on serpentine.”10 A mutant shrublike form (N. densiflorus forma “attenuato-dentatus”) grows in Yuba County in the northern Sierra Nevada.11 The mutant is used in horticulture due in part to its rarity and its unusual and beautiful narrow leaves, which are deeply toothed and taper to a very narrow apical tip. Given that this mutant’s maximum height is roughly eight feet, it adapts to small urban gardens much better than the full-size tanoak trees. In California, tanoak is more common than any other hardwood tree, which includes all flowering trees.12 Despite being abundant in much of its range, tanoak’s global distribution is very limited.

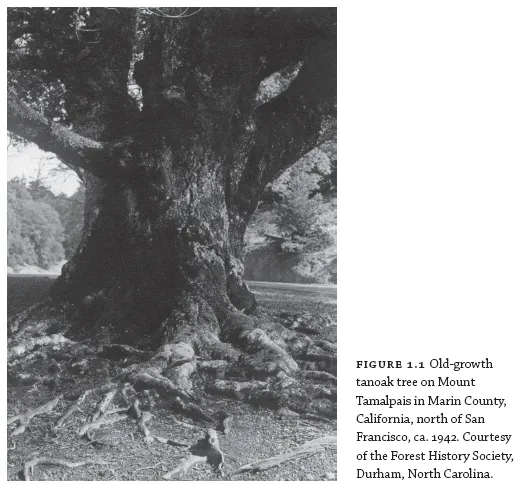

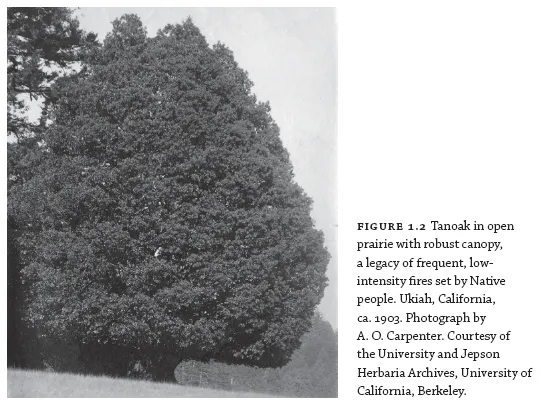

The most ancient trees are estimated to be as old as three hundred to four hundred years.13 According to the U.S. Forest Service, 109 inches is the largest diameter on record, which was measured on a 100-foot-tall tanoak in Humboldt County with a 76-foot-wide crown.14 Although significantly shorter at 65 feet in height, the limbs of another ancient tree reported farther south reached 60 feet in width. This enormous tree with a circumference of 227 inches grew near Rock Spring in Mount Tamalpais State Park, just north of San Francisco (fig. 1.1).15 Throughout its range, 180 years appears to be a typical maximum age in unlogged forests.16 It is often difficult to reliably determine the age of a tanoak due to heart rot and the high frequency of suckering if killed to the ground. Its hard wood also makes coring a tanoak trunk to count growth rings a challenge. Tanoak’s overall shape varies greatly depending on growing conditions, like other plants. However, two common forms of this evergreen tree exist, one in full sun (fig 1.2) and another in shade (see fig. 8.2). In open stands dominated by hardwoods or scattered in prairies, tanoaks form a broad, dense crown and a short trunk with robust horizontal branches that can reach to the ground. In shady, dense coniferous forests, tanoaks often grow as tall as 150 feet, with a branchless trunk that is clear for 30 to 80 feet.17 Taller trees with long trunks growing with coniferous competition lend themselves to wood production, while trees grown in sunny exposures generate a greater abundance of food in the form of acorns. Generally, the height of a medium-size tree typically ranges from 50 to 90 feet, with a maximum height recorded at 208 feet.18 Diameter at breast height in mature trees typically ranges from 6 to 48 inches.19

Willis Linn Jepson, a University of California botany professor from 1899 to 1937, wrote that tanoak is “exceptionally well-fitted by its reproductive powers, vigor and shade endurance to take part in the struggle for continuous possession of the land”—hence its other common name, sovereign oak.20 In response to fire, tanoak can quickly rise from the ashes when previously dormant epicormic buds are activated to sprout from a burl below or near ground level or from the root system. The ability to form a burl as a sapling makes tanoak well adapted to recover if it dies down to the ground after a frost, drought, or fire. Tanoak can be in a repressed state for a long time in the understory and spring to life when released from competition after conifer logging.

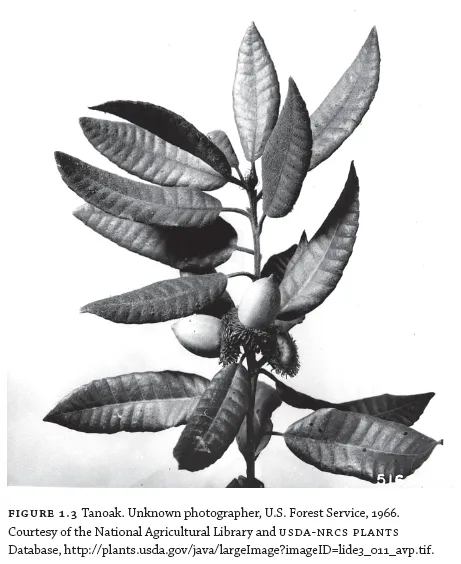

Tanoak is a resilient evergreen capable of withstanding drought and frost. Its simple leaves alternate on the stem. Notorious for being highly variable, the leaves are “leathery to brittle” with serrated to toothless edges and often revolute margins (fig. 1.3).21 The lateral veins off the midrib typically are parallel and unbranched all the way to the leaf margin, which lends the tree the appearance of being related to chestnuts. The usually smooth and shiny leaves are densely wooly on the underside initially, but much of the hair wears off with age.22 Dense hairiness on new leaves and young twigs reduces water loss. The thick, grayish-brown bark becomes fissured with age.

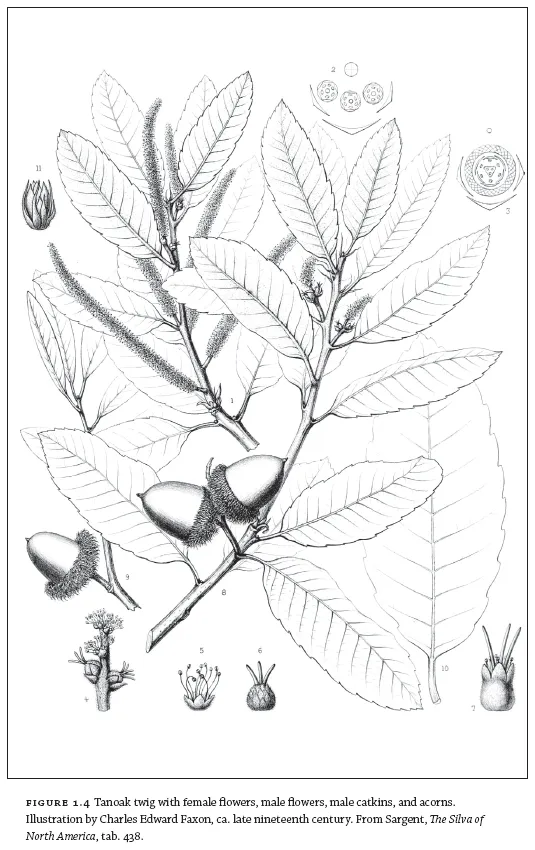

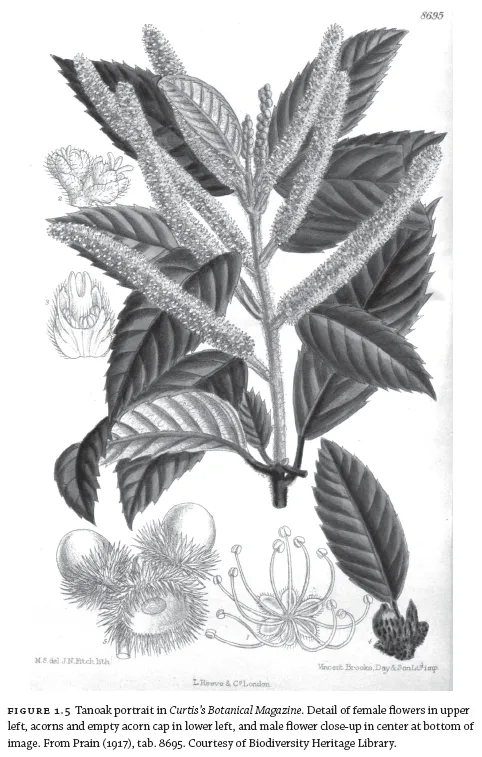

As is typical of the beech family (Fagaceae), tanoak produces separate female and male flowers on the same plant, a condition known as monoecism. Each small, simple unisexual flower lacks petals (fig. 1.4). Although each flower is tiny, collectively the males put on a show in a kind of inflorescence called a “spike,” with each flower lacking an individual stalk. In the words of Donald Culross Peattie, author of A Natural History of Western Trees, the abundant yellowish-white male spikes “light up the tree like candles at Christmas” (fig. 1.5).23 The small, solitary female flowers aggregate at the base of the erect male catkin, each subtended by a small bract. Tanoaks can flower in any season except winter, but blossoms typically appear in June, July, or August with coastal and low-elevation trees blooming earliest.24 Drought during pollination fosters greater seed set.25 Once pollinated, acorns mature after two years.26 Tanoak trees begin bearing acorns in abundance between thirty and forty years of age.27 Coppice growth in the form of burl sprouts can begin producing acorns as young as five years old.28

Although botanists, foresters, and plant pathologists have completed much research on tanoak, a full understanding of the organisms and ecological processes affected by it remains incomplete. Until recently, tanoak was widely believed to be wind pollinated, like oaks in the genus Quercus. Although self-fertilization does occur, and some wind pollination is likely, most female tanoak flowers are insect pollinated.29 Volunteer citizen scientists assisted in making this new discovery; however, the insect species observed remain to be systematically identified. Further research is recommended to study the significance of tanoak pollen as a food source in pollinator communities.30 Tanoak’s pollination ecology has multiple implications for conservation. Insect pollination can significantly increase genetic diversity within a plant’s populations, which can ultimately affect the plant’s ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

These nut-bearing trees feed numerous animal species. Many wildlife species cache tanoak acorns for later consumption, including acorn woodpeckers (Melanerpes formicivorus), Steller’s jays (Cyanocitta stelleri), and at least four species of squirrels.31 One tanoak nut hoarder, the dusky-footed woodrat (Neotoma fuscipes ssp. fuscipes), is an important prey of the northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis ssp. caurina). Other predators of tanoak herbivores include coyotes (Canis latrans), cougars (Puma concolor), and fishers (Martes pennanti).32 Because tanoaks produce their abundant nut crop in the fall, they provide a critically important food source for bear and deer that fatten on the acorns, building a reserve and insulating layer for winter. Even the now extinct, endemic California grizzly bear (Ursus arctos ssp. californicus) ...