![]()

1

UPLAND ALTERNATIVES

An Introduction

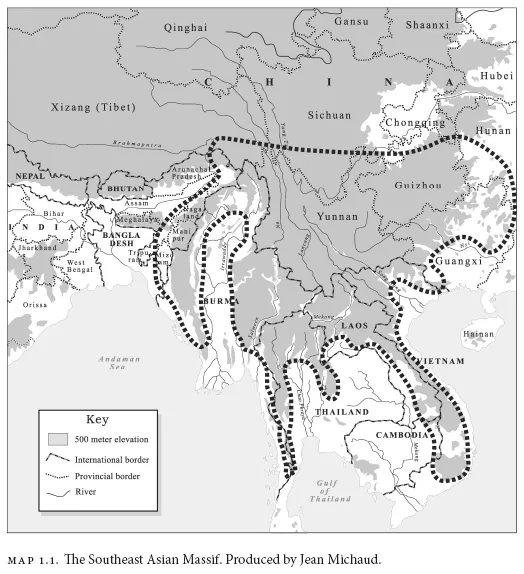

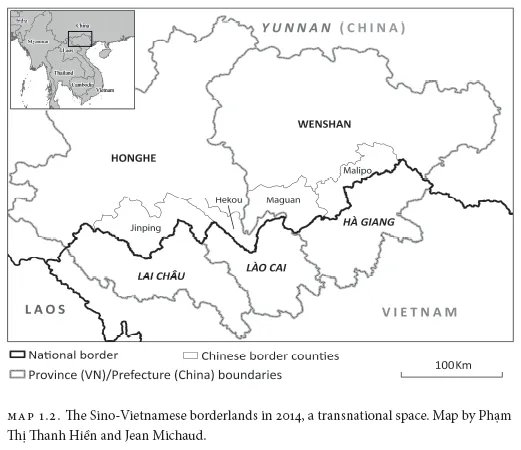

TWO HUNDRED MILLION PEOPLE, MORE THAN HALF OF WHOM ARE ethnic minorities, reside in the uplands of the Southeast Asian Massif, with livelihoods based predominantly on rural agriculture (map 1.1). In this book, we offer an examination of the predicaments, choices, and fates of members of one such minority group, known by its most common ethnonym, the Hmong.1 There are approximately four million Hmong in Asia (Lemoine 2005), spread, in decreasing order of population, over China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Burma, and conceivably Cambodia. More than a million Hmong live on the Vietnamese side of the Sino-Vietnamese border, and possibly as many live in Yunnan, on the Chinese side (map 1.2).

Relatively little is known about the livelihoods of these transborder Hmong individuals and households in China and Vietnam. Hmong residents of this frontier region face particular challenges as economic liberalization and market integration advance under the impetus of centralized political structures that maintain a strict communist leaning—a historically unique combination that specialists of Marxism might have thought paradoxical.2 In these borderlands, both states have rapidly instigated a push for modernization through investment programs and economic development schemes, backed by multilateral financing and the work of nongovernmental organizations on the ground. Since the onset of reforms in the 1980s that loosened the grips of these communist states over their then-flagging economies, collective property has been replaced with private land-use rights, cash cropping has been encouraged, and shifting cultivators have been strongly advised to become permanent, settled farmers. New infrastructure works such as highways, airports, hydroelectric projects, and communication networks, all support this modernization drive, which is frequently labeled “development.”

Dwelling at a distance from the seats of power, ethnic minorities on the physical, cultural, and economic fringes of China and Vietnam face tough choices. Their status is marginal, to put it mildly, which makes their task of evaluating livelihood options difficult. How can they, and how do they, combine and negotiate far-reaching choices regarding new liberal market economies, obligations, opportunities, identities, and livelihood diversification? Putting local agency at the center of our analysis, we ask: how do Hmong individuals, households, and communities in the Sino-Vietnamese borderlands make and negotiate their livelihood decisions? In what manner(s) are they adapting, diversifying, or sometimes disguising their actions? How do they shift their strategies to take on new imperatives, constraints, and opportunities?

In the early twenty-first century, some scholars foresee a global narrowing of livelihood choices as inevitable. The dilemmas that Hmong farmers face, they suggest, are part of a well-documented process that has been occurring worldwide as rural inhabitants undergo an agrarian transition toward wage work and large-scale cash-based agricultural systems designed to support increasingly urbanized and industrialized economies (Hart, Turton, and White 1989). This is even more pronounced in places such as China and Vietnam, where formerly collectivized communist economies rapidly switched to a market paradigm (Burawoy and Verdery 1999). Such syntheses of worldwide trends are useful, but their outcomes often seem entirely predetermined. While global processes can standardize practices on the ground, they also materialize with unique challenges across time, space, and cultures. These challenges can certainly trigger reactions of compliance, but they can just as well lead to debate, contestation, and struggle that require further scholarly attention (Edelman 2001; Hollander and Einwohner 2004; Kerkvliet 2009). Research by Willem van Schendel (2002) and the debates surrounding James C. Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (2009), for instance, show that there is more than meets the eye in the dilemmas at play in the Southeast Asian Massif.

Since the seminal works of Karl Polanyi (e.g., Polanyi 1944), many social anthropologists and human geographers have pleaded for the need to recognize “the cultural, historical, and spatial dynamics of rural livelihoods—in addition to the more obvious economic dynamics” (McSweeney 2004, 638). Such recognition requires a nuanced understanding of a place’s social connections, embedded as they are in local histories, customs, and systems of regulation that shape economic exchanges and the decision making surrounding them.3 Only by factoring in these localized layers of complexity can any well-intentioned research on livelihoods and household endurance strategies in the Global South be effectively advanced and stand a chance of yielding lasting results.4

Social anthropologists, for whom studies at the micro level are frequently the norm, find this obvious, and many human geographers and progressive-development specialists concur. But many economists and experts of macro-development discard the approach as a well-meaning but naïve ideal, bound to waste precious time and energy in the face of pressing national programs, global economics, and environmental challenges. This book is aimed at such skeptics. We hope to show that there is much more to this intricate equation than global formulas and bottom lines.

Yet, a livelihood approach can be limited by its inclination to focus primarily on aspects of material access and capital, often ignoring less palpable social and political influences (Kanji, MacGregor, and Tacoli 2005; Scoones 2009; Carr 2013). Such an approach is prone to producing only a cursory examination of social factors, including gender and age, with regard to differential access to resources and decision making (Hapke and Ayyankeril 2004). Focused on recurrences and patterns as it is, the livelihood approach tends to disregard local peculiarities (deemed unreliable) in favor of well-tested generalizations (deemed functional). The mechanistic and somewhat positivist focus on identifying and analyzing five specific forms of assets or capital—an approach commonly adopted by global development agencies such as the United Nations Development Program (UNDP)—generally produces a “one size fits all” methodology that often fails to take into account agency at the local level. This focus also produces the potential for indiscriminating action by state agents on the ground (Arce 2003; Hinshelwood 2003; Staples 2007).

Consequently, calls continue to be made for more inclusive, culturally specific, actor-oriented approaches to livelihoods that consider microscale social relations and their embeddedness within local socioeconomic, political, and cultural systems.5 By listening to the voices and experiences of individual actors regarding homegrown knowledge of “development,” and the way actors adapt modern circumstances to their reality, one can bring to light the local, everyday practicalities of how people make and defend their livings and their visions of the world. This approach allows for a comprehensive recognition of locally rooted livelihood dynamics alongside broader structural forces (Arce and Long 2000; Bebbington 1999, 2000; Long 2000).

The decisions of Hmong individuals and households illustrate how livelihood diversification strategies might include engaging in new income opportunities, experimenting with different crops, or combining agricultural, livestock, and off-farm activities (Chambers and Conway 1991; Rigg 2006).6 Market integration, agrarian change, and globalization processes present unprecedented challenges for these borderland residents. In response, households adopt fluid and innovative diversification approaches to survive, remain resilient and secure, and prosper (cf. de Haan and Zoomers 2003; Eakin, Tucker, and Castellanos 2006). In this borderland context, the malleable nature of livelihoods has been largely overlooked by academics, state officials, and aid agency workers to date (Bouahom, Douangsavanh, and Rigg 2004). Indeed, with broader economic contexts being in a state of flux, the degree to which livelihoods are continuously refashioned and negotiated—and the agency of those involved—has often been underestimated or misjudged.

Because the three of us have spent years talking with individuals at the receiving end of development schemes across the Southeast Asian Massif, and in the Sino-Vietnamese borderlands in particular, and because we feel that the dominant mindset toward “developing them” is far from optimal, we offer a locally adapted, nuanced analysis of rural livelihoods. The first way we do this is by drawing upon the notion of agency (Ortner 2006). To disentangle what we mean by this, we highlight debates regarding alternative modernities and the “indigenization of modernity” (Sahlins 1999), in conjunction with actor-oriented approaches that draw on the concept of “social interface” (Long 2001, 2004). An important component of an individual’s agency is the ability to decide when to comply with or oppose outside influences, hence the relevance also of everyday politics and resistance (Scott 1985; Kerkvliet 2009). Second, we examine debates surrounding borders, namely the roles, relationships, and contestations of borderlines, borderlands, fringes, and frontier regions. In this way, drawing on livelihood and borderland debates as well as the implications of agency and the indigenization of modernity, everyday politics, and resistance, we suggest a framework to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of how rural Hmong inhabitants in the Sino-Vietnamese borderlands navigate, rework, contest, and appropriate specific facets of identity, modernity, market integration, and nation-state building as they go about creating resilient life-worlds and everyday livelihoods.

THE IMPLICATIONS OF AGENCY

CREATIVE ADAPTATION, THE INDIGENIZATION OF MODERNITY, AND AGENCY

Modernity is one of those catch-all terms that is debated across disciplines.7 Perhaps the most recognized interpretation of modernity is societal modernization, which has been encapsulated by the modernization theory of development studies. This linear-trajectory approach includes the “emergence and institutionalization of market-driven industrial economies, bureaucratically administered states, modes of popular government, rule of law, mass-media, and increased mobility, literacy, and urbanization” (Gaonkar 1999, 2). In such narratives, a distinction has historically been made between the “West” and the “rest”—“traditional” or “premodern” societies. The economic development pursuits of the Chinese and Vietnamese governments overwhelmingly follow such an approach in their teleological drive for economic growth, the development of a bureaucratic state, and the eradication of “backwards customs and superstitions” (Qian Chengdan 2009; Li 2011). Proponents of this acultural theory consider the transition to modernity to be a collection of culturally neutral (and highly desirable) processes.

Alternatively, a slew of anthropologists and other scholars have examined the ways in which modernization as actualized is far from acultural. For instance, Charles Taylor (1999, 153) raises the possibility of a “plurality of human cultures, each of which has a language and a set of practices that define specific understandings of personhood, social relations, states of mind/soul, goods and bads, virtues and vices, and the like.” Instead of presupposing the decline and end of traditional societies and the ascent of modern ones, as acultural notions of modernity would, cultural theories attend to how modernity processes are inflected by culture, history, and politics (Featherstone and Lash 1995; Michaud 2012). They consider the ways in which alternative modernities are produced “at different national and cultural sites. In short, modernity is not one, but many” (Gaonkar 1999, 16).

For ethnic minority communities in the Southeast Asian Massif, modernity incorporates a convergence of institutional arrangements—such as a market economy and bureaucratic state—alongside a “divergence . . . of lived experience and cultural expressions of modernity that are shaped by what is variously termed the ‘habitus,’ ‘background,’ or ‘social imaginary’ of a given people” (Gaonkar 1999, 16). As such, our focus is on the “site-specific ‘creative adaptations’ on the axis of convergence” (ibid.).

The vast majority of Hmong households in these uplands are busy with daily agricultural and rural livelihoods. Some are eager to take up new opportunities and diversification strategies that might make life easier, such as new farming techniques, high-yield crop varieties, cash crops, and trading networks extending beyond customary ethnic circles. Moreover, outside the mainstay of farming life across the Massif, many Hmong individuals are exploring their options, working for wages on construction sites, buying and driving taxis, engaging in transnational trade, texting their kin and chatting on QQ, setting up Facebook pages, learning European languages, or pursuing tertiary education nationally and abroad. Like any other minority group in these uplands, Hmong individuals are adopting market economic opportunities and state policies and programs as they see fit. However, these creative adaptations do not signal a straightforward acquiescence with modernization’s wishes; to suggest that would be to close one’s eyes to the existence of more subtle signs of diversion and dissent.

Sherry B. Ortner proposes that, “to some extent, and for a variety of good and bad reasons, peoples often do accept the representations which underwrite their own domination” (1995, 182). However, she adds, “at the same time, they also preserve alternative ‘authentic’ traditions of belief and value which allow them to see through those representations” (ibid.). Further, Marshall Sahlins (1999) developed the idea that modernity—or any global command—can be “indigenized” locally, suggesting that economically and politically weak groups are indeed changed by outside pressures, but also creatively use what power they have to interpret, adapt, and even subvert them (cf. Babadzan 2009). Our argument echoes Sahlins’s proposition that “local societies everywhere have attempted to organize the irresistible forces of the Western World System by something even more inclusive—their own system of the world, their own culture” (2005, 47).

Considerations of how global edicts are invested locally with fresh meaning point to agency—the power to act—as a pivotal notion. Saba Mahmood (2004, 29) thinks of agency “(a) in terms of the capacities and skills required to undertake particular kinds of moral actions; and (b) as ineluctably bound up with the historically and culturally specific disciplines through which a subject is formed.” Ortner similarly notes, “In probably the most common usage, ‘agency’ can be synonymous with the forms of power people have at their disposal, their ability to act on their own behalf, influence other people and events, and maintain some kind of control in their own lives” (2006, 143–44). Like Mahmood, Ortner argues that agency is not an entity that exists apart from cultural construction: “Every culture, every subculture, every historical moment, constructs its own forms of agency” (ibid., 186). As agency appears and evolves in context, it must be studied in relation to the circumstances that have formed the actors.

ACTOR-ORIENTED ANALYSES AND THE SOCIAL INTERFACE

In a similar vein, adherents of the actor-oriented perspective, anchored in the literature of development sociology and anthropology, have also reacted against earlier metanarratives that emphasize structural constraints. These metanarratives have been criticized for their inability to explain location-specific differences in development, while overemphasizing macroscopic economic determination (Korovkin 1997; Hebinck, den Ouden, and Verschoor 2001). Actor-oriented proponents argue instead that any transformation occurs via the mutual and inescapable interplay between internal and external factors, thus shedding new light on the power of human agency to mediate structural changes in creative and locally rooted ways.

Useful here is Norman Long’s notion of the “social interface,” which emphasizes that, as Arturo Escobar (2001, 139) puts it, “culture sits in places.” Long argues that to fully comprehend the everyday processes by which “images, identities, and social practices are shared, contested, negotiated, and sometimes rejected by the various actors involved” (2004, 16), one must analyze the extent to which the life-worlds of specific actors, including their social practices and cultural perceptions, are simultaneously autonomous and “colonized” by the more extensive frames of ideology, institutions, and power. He suggests that it is these interplays of everyday life and wider structural forces that comprise social interfaces. Interface encounters can be in person between individuals or can be mediated via additional actors, even absent ones, who still influence local outcomes. At these interfaces, different life-worlds intersect and interests, values, knowledge, and power are challenged, mediated, and transformed. Long (2000) advocates for the documentation of these interfaces through careful ethnographic investigation—a call to which we wholeheartedly respond.

The refined actor-oriented approach of recent years allows us to engage across spatial scales of analysis to better understand structures that influence daily livelihood decisions, and to uncover the “micro-foundations of macro-processes” (Booth 1993, 62). We do not wish to underestimate the constraints that hierarchical structures impose upon Hmong livelihoods, nor overestimate the capacity of Hmong individuals and households to influence or alter changes that are taking place. We carefully weigh the balance between individual actions and institutional or historical constraints. As Ben Jones put it, “We try to remain open to individual interests while understanding the ways in which cases relate to broader changes in the social landscape. Individuals, or groups, . . . are seen to use their relative power; their capacity to argue for certain outcomes; or their desire to privilege certain discourse; and are thus able to draw on past experiences in bringing new things into being” (2009, 29).8 Discrepancies in knowledge, power, and cultural interpretation are mediated, perpetuated, or transformed at critical points, whether these be points of linkage or of confrontation (Long 2001). These complex negotiations trigger the vernacularization—or cultural adaptation—of global commands and processes along the lines of local knowledge and belief systems (Long and Villarreal 1993; Engel Merry 2006; Michelutti 2007). Such mediations and transformations can occur through, among other routes, the use of everyday politics and resistance.

EVERYDAY POLITICS AND COVERT RESISTANCE

In trying to understand the complexities of making a living in the socialist Sino-Vietnamese uplands and how individuals there use their relative power to indigenize modernity, everyday politics and covert resistance deserve attention. In asserting agency, individuals draw on a variety of covert as well as overt actions while engaging with change. Yet, to date, the livelihoods literature has tended to underplay the significance of local peoples’ everyday politics, especially in unyielding authoritarian contexts such as communist regimes. In numerous cases of development policy and practice, a mainstream livelihood approach is typically mobilized to strategize economic development (Forsyth and Michaud 2011; Turner 2012a). By maintaining this focus, researchers and developers frequently lose sight of t...