![]()

CHAPTER 1

IMPERIAL REPERTOIRES IN REPUBLICAN XINJIANG

IN HONING THEIR TOOLS OF GOVERNANCE IN XINJIANG, HAN officials looked to both domestic precedent and foreign models. Their source for investigating the former is readily apparent: for the first two decades after the 1911 revolution, nearly all Han officials in Xinjiang were veterans of the Qing state, claiming extensive experience in the old imperial bureaucracy. Most of them were intimately familiar with Qing repertoires of rule and had an extensive literature of former imperial precedents at their fingertips. But what about their knowledge of contemporary European and Japanese models? The journey from Urumchi to Beijing, undertaken on camel and horseback well into the 1930s, could take upward of three months to complete. Clear into the 1940s, Xinjiang was notorious for the extent of the information blockade imposed upon its inhabitants by a series of Han warlords. The telegraph system was in perennial shambles, earning the derogatory nickname of “camelgraph” from the Russians. As a result, the conventional view of Han officials in Xinjiang has been that they were of a rather parochial and reactionary mindset, scarcely interested in the outside world. Writing about Governor Yang in 1917, Xie Bin, an envoy from the central government, concluded that “his mind is too steeped in the old ways of thinking and his convictions are too deeply imprinted. He has served as an official in the northwest for too long and knows nothing of intellectual currents in the outside world. He will prove unable to row his boat with the tides of progress.”1

Xie may have been surprised to learn just how informed about the outside world both Yang and his former Qing colleagues in Urumchi actually were. In 1909, Liankui, the Manchu governor-general for both Gansu and Xinjiang and Yang’s superior at the time, was tasked with overseeing provincial elections and the formation of a parliament for Xinjiang. After noting the miniscule proportion of Han in his province and the almost total lack of educated Han gentry, Liankui proceeded to regale the central government with his extensive knowledge of ethnopolitics in other contemporary empires. “In governing their dependent territories,” he wrote, “both Eastern and Western states employ special methods. The British in India and the French in Vietnam, for example, both maintain an autocratic form of government.” After citing Herbert Spencer’s The Study of Sociology, Liankui outlined three types of government in European empires: settlement colonies subject to a monarch, dependencies with representative organs but no cabinet, and those with both representative organs and a cabinet. In those dependencies where “white people are many but natives are few,” the “degree of civilization” made it possible for “the state to grant them self-governing powers.” Thus, according to Liankui, until Xinjiang made significant strides in either developing education among the non-Han peoples or resettling droves of educated Han to the northwest, the province was not prepared to undertake elections.2

As was made evident in the discourse on Hokkaido and Taiwan, the once prevalent view of Chinese officials on the frontier as doddering relics of an intellectual and cultural backwater is almost entirely baseless. While they may have striven to limit the contact their subjects had with the outside world, the Han governor and his ranking officials in Urumchi were fully enmeshed in the intellectual and political currents of a cosmopolitan imperial elite. Wang Shunan (1851–1936), the provincial treasurer of Xinjiang during the final years of the Qing dynasty, provides us with an excellent example. Born into a literati family in Hebei, Wang worked his way up through the traditional examination system before serving as a magistrate in Sichuan for eight years. After coming to the attention of Zhang Zhidong, one of the most vigorous reform officials of the late Qing, Wang worked on various modernization projects in the Yangzi delta, coming into frequent contact with Chinese students returned from Europe. An ardent admirer of Japan, Wang was sent in 1898 to escort Western-style munitions to suppress a Muslim rebellion in Gansu, just southeast of Xinjiang. Wang would spend much of the next two decades in the far northwest, obtaining a transfer to Xinjiang in 1906.3

Just as important as his political career, however, were Wang’s scholarly labors. During his time in Gansu, Wang wrote five books concerning the history of various European countries, with the goal of identifying the source of their wealth and power. By the time of his death, Wang had authored or edited histories of Greek philosophy and of great wars in European history, a massive gazetteer of Xinjiang, the official history of the Qing, and a history of Russia under Peter the Great. Among his voluminous publications, some are notable as the first-ever treatment of their subject in China. More germane to our purposes here, most of Wang’s works on European history and culture were written during his time in Gansu and Xinjiang and published in Lanzhou, far from the traditional centers of Chinese scholarship. When the famous French sinologist Paul Pelliot passed through Urumchi in 1907, he was delighted to find so many cosmopolitan savants among Wang’s entourage. Wang, “a man of great learning” and a “very esteemed scholar,” asked Pelliot to lend him astronomical instruments for some scientific experiments. After noting a few places in need of revisions in Wang’s history of Peter the Great, Pelliot was “overwhelmed” by local officials hoping to pick his brain. One asked Pelliot to write several pages summarizing the last two centuries of developments in European philosophy, while another asked him to pen an article describing the financial conditions of loans and interest rates in Europe, with an eye toward eliminating the usurious practices of Hindu moneylenders in Kashgar.4

Wang is so important because he presided over a patron-disciple relationship with Yang Zengxin, the future Republican governor of Xinjiang (1912–28). Indeed, over a relationship that would ultimately span more than three decades, Wang secured Yang’s transfer to Xinjiang from Gansu, contributed several prefaces to Yang’s Records from the Studio of Rectification, authored the epitaph for the tombstone of Yang’s father, published a book of poetry in praise of Yang, and carried out a host of political assignments on Yang’s behalf in Beijing. In return, Yang financially supported Wang and his entire family for nearly twenty years after the latter’s departure from Xinjiang. Thus it seems safe to say that Yang, the governor of Xinjiang for nearly two decades after the 1911 revolution, was able to partake amply of the global knowledge economy of imperial governance as distilled in his patron’s writings. Nor were Wang and Yang unique among Chinese officials in Xinjiang. The large volume of travel writings left by Western archaeologists and explorers who visited Xinjiang during these decades suggests that many—though by no means all—of Yang’s subordinates were similarly eager to learn about the latest developments abroad. In 1906, when Finnish traveler and future statesman Gustaf Mannerheim passed through the southwestern oasis of Kashgar, he noted how “during our visits to the Chinese authorities they were interested in informing themselves about the political situation in Russia,” and that they “expressed the conviction that H.M’s government will not be long-lived and that their mighty neighbour is moving towards a republican form of government.”5

Their interest in Russia was not misplaced. As with so many other areas of modern Chinese history, developments in the Russian empire often constituted a preview of social and political vicissitudes that were soon to shake China. Nowhere does this realization come through more clearly than in the response of Han officials in Xinjiang to the evolving imperial repertoires deployed by their Russian counterparts. Russian officials in and around Xinjiang first showed Han officials how to turn their newfound imperial liabilities into nationalized assets. Though political elites throughout China were closely attuned to strategies of difference practiced in the British, French, and Japanese empires, those practiced in the Russian empire would ultimately determine the geopolitical and ethnocultural configurations on display in today’s People’s Republic. Due to Russia’s geographical proximity, superior military technology, transportation networks, and economic resources, Han officials posted along the northern and western borderlands ignored their neighbor at their own peril. In fact, more often than not, whenever Han rulers saw fit to import Russian political innovations into their own non-Han jurisdictions, they did so as part of a defensive strategy designed to counterbalance an offensive version of the same tactic first introduced by the Russians.

The concept of imperial repertoires is essential to understanding the specific types of institutions and strategies of difference employed in support of late imperial and early Republican rule in Xinjiang. These can be thought of not as “a bag of tricks dipped into at random nor a preset formula for rule,” but rather the evolving tools of governance that imperial elites could envision on the basis of past precedents, cultural habits, geopolitical context, and rival innovations.6 Flexible in nature, they tended to evolve from a pragmatic impulse to pursue the path of least resistance in securing the loyalties of diverse constituencies. At any given moment during the twentieth century, the changing repertoires of Chinese rule in Xinjiang are best viewed as a sort of administrative cabinet of “best practices,” an imperial portfolio of governing tactics whose contents were culled from domestic precedent and contemporary foreign models. Successful Chinese rule in Xinjiang during the twentieth century depended upon up-to-date knowledge and innovative application of portable repertoires of differentiated rule then circulating through the various empires of Eurasia.

A number of specific precedents would have been familiar to Governor Yang as he assumed his new post in 1912, less than a year after the Wuchang uprising: territorial accommodation, dependent intermediaries, supranational civic ideology, deflection of ethnic tensions, and narratives of legitimacy.

TERRITORIAL ACCOMMODATION

The institutionalization of difference in units of territorial administration has long been a hallmark of empire. For most of the imperial era in China, the driving force behind such demarcations was the “northern hybrid state.” These political entities combined the military advantages of an Inner Asian conquest elite with the cultural, economic, and administrative resources of the Han heartland. The largest and most successful empires in continental East Asia invariably evinced strong northern and northwestern associations.7 Whenever pastoral peoples from the “northern zone” managed to incorporate the sedentary agricultural communities of the south into their state, however, they continued to treat the Han heartland as a distinct economic, cultural, religious, and political unit. While the “inner provinces” (neisheng) were intended to provide most of the wealth, labor, administrative knowledge, and cultural resources necessary to run a massive empire, Mongolia, Tibet, Manchuria, and Xinjiang were chiefly envisioned as strategic bulwarks unique to the geopolitical concerns of an Inner Asian conquest dynasty. As such, they were not expected to finance their own administrative and military expenses, and instead drew massive subsidies of silver—known as “shared funds” (xiexiang)—from the wealthy interior. Their special status was captured in the name of the government office tasked with their administration during the Qing: the Court for Managing the External (Lifanyuan). Whether envisioned as a “dependent territory” (shudi) or an “outer dependency” (tulergi golo in Manchu), the point was that Xinjiang and other non-Han territories were different, and this difference should be recognized in the territorial institutions through which they were governed.8

In practice, this meant that a political map of Qing Xinjiang would have evinced composite layers of jurisdictional units, which claimed varying degrees of autonomy and ties with Beijing. Some of these geographical units—Ili, Tarbagatai, and Khobdo among them—were governed by Manchu and Mongol bannermen dispatched from Beijing. Others, such as the Muslim khanates of southern and eastern Xinjiang, were hereditary fiefdoms granted by the Manchu court to the descendants of the indigenous Turkic supporters of the initial Qing conquest of Xinjiang in the 1750s. Muslim princes retained control over the taxproducing resources of their districts, the most prominent of which were located in Hami, Turpan, Kucha, and Khotan. Though cultural and social links persisted among these Muslim khanates, the relationship was ultimately oriented toward Beijing, where each prince and his entourage were expected to participate in a periodic round of pilgrimage to present tribute to the emperor. The end result very much resembled a so-called hub-and-spoke patronage network, “where each spoke was attached to the center but was less directly related to the others.” Ideally, horizontal intercourse among the constituent parts—such as marriages—could be undertaken only through the center (Beijing).9

During the first decade of the republic, this patchwork legacy of territorial and administrative layering induced seemingly unending political headaches for Governor Yang Zengxin. Faced with numerous geopolitical crises in and around these semiautonomous regions, Yang found it almost impossible to force their officials to do his bidding. Making matters even more difficult for Yang was the fact that his rivals enjoyed their own lines of communication with Beijing, thereby allowing them to bypass the governor’s censors in Urumchi. It should come as no surprise, then, to learn that Yang made it a high priority to eliminate these autonomous jurisdictions. From 1915 to 1921, the governor, aided by geopolitical crises occasioned by the Russian civil war, successfully lobbied for the abolition of the Ili general, Tarbagatai councilor, and Altay minister. In fact, the present-day borders of Xinjiang are largely a result of Yang’s efforts to create an administratively homogenous provincial unit free from internal challenges to his rule.

Yet a crucial caveat is in order. Whereas Yang was only too happy to aggrandize the authority of those (mostly) Han officials sent by Beijing to fill military posts once reserved for the Inner Asian conquest elite, he did not apply the same model of aggrandizement to the indigenous non-Han nobility of the province. Partly this was for the simple reason that the Qing court had already done away with most of them. By the time Yang became governor, the Muslim princes of Turfan, Kucha, and Khotan existed in name only, having been divested of their economic and military prerogatives during the reforming zeal of the late Qing. Yet the prince of Hami, Shah Maqsut, still lorded over his khanate in both name and substance. Yang Zengxin, over a period of nearly two decades, never saw fit to continue the late Qing trend of depriving the indigenous Muslim nobility of Xinjiang of their hereditary privileges by eliminating the last Muslim prince of Hami. In fact, he often decried the integrationist thrust of late Qing reforms in Xinjiang, lamenting how Xinjiang had become a “colony” (zhimindi) of the inner provinces.

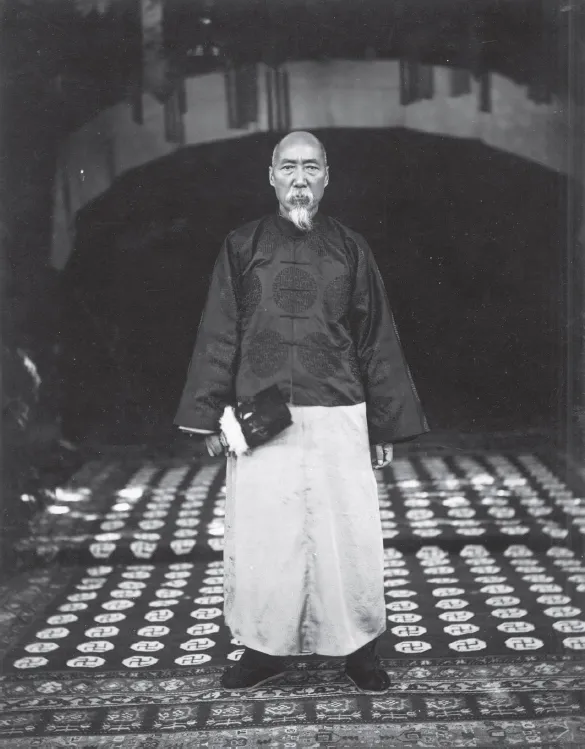

FIGURE 1.1. Yang Zengxin, governor of Xinjiang, 1912–28. The longest-serving governor in the history of Xinjiang, Yang consistently promoted a conservative ethno-elitist platform and was quick to suppress all nationalist platforms, including those that valorized “the yellow race.” He was assassinated in July 1928, mere months after this photograph was taken. Sven Hedin Foundation collection, Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm.

The cumulative picture to emerge from Yang’s efforts, then, is as follows. Regarding as a mistake the designation of Xinjiang as a province in 1884, Yang moved to restore a foundation of institutionalized difference in Xinjiang, which he regarded as a land distinct from the inner provinces. To do this, he needed to eliminate those semiautonomous offices traditionally filled by appointees from Beijing, for these extended into Xinjiang a volatile continuity with the centralization and integrationist efforts of the late Qing state. In their place, Yang staffed his provincial bureaucracy with veteran Qing officials of the northwest and reserved criticism for those who ventured to govern the non-Han borderlands without prior experience in the field. In effect, he was recreating the principles of territorial accommodation once prevalent in Xinjiang prior to the last decades of the Qing, complete with a new occupational caste modeled on the Inner Asian conquest elite once assigned sole responsibility for the non-Han borderlands. These men were Han officials who had spent most, if not all, of their careers in the northwest.

Without a doubt, Yang manipulated this legacy of territorial difference for his own purposes. Yet part of the reason he managed to stay in power for seventeen years is precisely because he recognized the very real conditions of difference bequeathed him by his Qing predecessors. According to Yang, Xinjiang, though still a province in name, must be treated differently from the Han heartland. Otherwise, as he was fond of telling anyone who would listen, it just might become “the next Outer Mongolia.” In 1955, the Chinese Communists, in repudiating Xinjiang’s provincial status and designating it the Uighur Autonomous Region—effectively restoring the early Qing distinction between “inner...