![]()

1 | Lost in Translation: Globalization 2.0 |

“It has been said that arguing against globalization is like arguing against the laws of gravity.”

—Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations

AT A GLANCE GLOBALIZATION 2.0

Five Essential Points

- Globalization 2.0 is fundamentally different from version 1.0. The East will progress from just being the workplace of the West; Western companies will still operate in the East, but under different circumstances. Goods, people, and capital will flow in multiple directions, not just from West to East, but also very much from East to West.

- Traditional trade patterns will be disrupted. As economic power shifts eastward, trade between emerging markets will flourish. The East will rely less and less on the West for goods and services. Organizations will need to think differently about marketing.

- Beware of “glocalization.” New middle classes will emerge in more and more countries, each with its own set of consumer demands, thereby “glocalizing” the market. A single, centralized strategy and operating model will no longer be adequate for multinational organizations.

- The burden of complexity will intensify. Globalization 2.0 will demand a complexity of thinking that few organizations or leaders have encountered—significantly intensifying the cognitive and, in particular, the conceptual and strategic demands on already overstretched leaders.

- Contextual awareness will be critical. Organizations will need to be more adaptable and encourage diversity of thought, in order to enhance their contextual awareness and ensure that communication is truly two-way.

Five Questions Business Leaders Should Ask

- How agile is my organization?

- Are our strategy and operating model adapted to the demands of different regions?

- How nimbly can we react to local demands?

- Will the next generation of leaders come from the local population, or will we need to import talent?

- How can we ensure that our leaders are equipped with the conceptual and strategic demands required for the demands of the new globalization?

Ten years ago, this book would have been written on American laptops, designed and engineered by IBM. But the company that revolutionized computing in the 1980s famously sold its PC manufacturing arm to Lenovo in 2004. So now here we are, tapping away on Chinese-made machines.

Three or four years back, one of us drove a Volvo, the other a Land Rover. Once the pride of the Swedish automotive industry, Volvo sold its car division to Ford in 1999. Ford also acquired Land Rover from BMW in 2002. The American manufacturer subsequently sold Land Rover to Indian carmaker Tata Motors in 2008, and Volvo to China's Geely in 2010.

And a year ago, when one of us needed to replace an old Grundig TV, friends recommended Philips, a European leader in technology, design, and engineering. The day the new set was delivered, the Dutch electronics giant announced the divestment of its TV division to a joint venture with Hong Kong's TPV Television. Philips now has a 30 percent minority share.

So only recently, between us we owned American computers, Swedish and British cars, and a German TV—all decidedly Western. Today, these appliances are Chinese and Indian. What happened?

Welcome to the world of Globalization 2.0.

THE HISTORY OF GLOBALIZATION

Before examining what happened, let's briefly refresh our memories of what has characterized globalization until now. We'll call this Globalization 1.0.1

Under Globalization 1.0, West went East. Western corporations sought cheaper production in less developed markets. They transferred labor and manufacturing facilities to distant locations, exporting their products back to their home markets at a fraction of the cost of domestic production. These distant locations were principally in the East: India, China, and the Far East (and in the case of some U.S. companies, Latin America). To put it crudely, the East became the sweatshop of the West.

Globalization 1.0 is nothing new. The process is hundreds of years old at the very least, possibly older. We might argue that it goes back to the Silk Road or the sea traders of ancient times. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) calls it “an extension…of the same market forces that have operated for centuries at all levels of human economic activity.”2

The phenomenon really took hold during the second half of the twentieth century, when technological innovation and international liberalization created the conditions for it to flourish. The twentieth century was, of course, a time of great technological advancement. Global travel, international freight, and long-distance communication became considerably easier, not to mention cheaper. And the advent of information technology enabled organizations to systemize and manage work, processes, and transactions happening thousands of miles away. Innovation decimated the time, cost, and practical barriers associated with doing business across borders.

At the same time, bureaucratic barriers also crumbled. The liberalization of international regulation occurred on an unprecedented scale. The peace that followed two devastating world wars allowed the creation of international pacts and free trade areas, such as the European Economic Community that was formed by the Treaty of Rome in 1957. Hurdles to cross-border trade fell away. Commerce, labor, and capital were able to flow between countries at hitherto unseen levels.

However old Globalization 1.0 may be, like it or not, it's a given. We cannot choose whether or not to accept or participate in it. The world is globalized, and it has been for some time. But globalization as we know it is changing.

What Is Globalization?

In its widest sense, globalization isn't a single topic. It's several all at once. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy points out, globalization covers a “wide range of political, economic, and cultural trends.” It can be defined variously as the pursuit of liberal, free market policies in the world economy; the dominance of Western forms of political, economic, and cultural life; the proliferation of new information technologies; and even the grand notion that humanity stands at the threshold of realizing one single unified community.

But thankfully, social theories have in recent years converged on a generally agreed upon definition. Broadly speaking, globalization is the compression of space and distance as the time it takes to connect geographical locations is reduced.3 This is the force that gave Globalization 1.0 a turbo-boost during the last century (see above).

In other words, the world is getting smaller.

This definition has been discussed by philosophers for 200 years or more. It may come as a surprise to learn that Karl Marx viewed this compression as, at least in part, a positive force. In the Communist Manifesto of all places, he and Friedrich Engels predicted that it would bring about the “universal interdependence of nations.”4 The German philosopher Martin Heidegger was less welcoming. He bemoaned this “abolition of distance,” issuing a bleak warning that “everything gets lumped together into uniform distancelessness.”5

More recently, the IMF provided a more strictly economic definition, one very much aligned with our concerns in this book. In 2000, an IMF paper described globalization as “the increasing integration of economies around the world, particularly through trade and financial flows.” The term also encompasses the movement of people, knowledge, and technology across international borders, the report pointed out.

The paper also defines four “basic aspects” that make up globalization. These are trade and transactions; capital and investment movements; the migration and movement of people; and the dissemination and exchange of information, knowledge, and technology.6

The IMF report also brings an economic logic to the compression of time and space described by our philosophers and social theorists. Globalization, it says, is the “result of technological advances that have made it easier and quicker to complete international transactions—both trade and financial flows.”

In other words, the world is getting smaller.

THE MEGATREND: GLOBALIZATION 2.0

The twenty-first century is witnessing the emergence of a parallel phenomenon to Globalization 1.0: Globalization 2.0. East is now also going West. Everything we thought we knew about the economic, commercial, and financial world is being turned upside down.

An important point to note here is that the new model does not replace the old. Globalization 1.0 goes on. Western multinationals will continue to operate from distant, low-cost bases. In June 2012, as the UK geared up for the Queen's Diamond Jubilee, The Times of London reported that souvenir tea towels were on sale in London at £4.25 per pair, sourced in China for just 9.1 pence (about 15 cents) each.7

Though the locations are changing, many of these low-cost bases will still be in the East. However, of the so-called Next 11 emerging countries identified by Goldman Sachs in 2005, seven are in Asia (Bangladesh, Indonesia, Iran, Pakistan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Vietnam). The list contains only one European nation (Turkey), as well as Mexico, Nigeria, and Egypt.8

But Globalization 2.0 is a different beast compared to its predecessor. It is not model 1.0 in reverse. Rather, it is characterized by two unique and interrelated attributes: (1) the shift in the economic balance of power to Asia, and (2) the rapid expansion of the middle class in the emerging nations.

The Asian Century

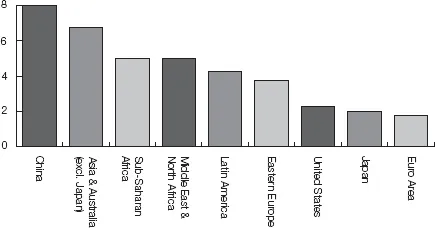

There is a wealth of statistical evidence documenting the rise of Asia as an economic power. China has been the fastest growing economy for the last thirty years, growing nineteen-fold in real terms over three decades since 1980.9 Market saturation and the economic crisis in the West are causing growth prospects there to practically stagnate—or, in many cases, leading to out-and-out recession. Meanwhile, Asian policy makers are frustrated that growth in the East is struggling to regain the double-digit acceleration it was experiencing before the financial crisis of 2008. The chart below summarizes GDP growth in 2016, as estimated by the Economist Intelligence Unit's World Economy Forecast of March 2012.

Figure 1-1 Estimated GDP Growth in 2016

In the race for economic growth, East is beating West hands down. But simply outperforming Western economic superpowers does not equate to a power shift. The tipping of the balance can be seen in the comparative scale and influence between East and West resulting from this reversal of economic fortunes.

In April 2011, the IMF provoked dramatic headlines across the world by forecasting that China would surpass the United States as the world's largest economy in purchasing power terms as soon as 2016.10 According to PwC, India is on course to overtake the United States on the same basis by 2050, at which point China's economy will outstrip America's by some 50 percent. Come this time, just three of the world's top ten economies will be from the West: the United States, Germany, and the UK.11

With scale comes influence; with economic scale comes financial influence. China's foreign exchange reserves totaled $3.2 trillion in February 2012.12 In May of the same year, the country's state-owned investment fund, the China Investment Corporation (CIC), was sitting on assets worth $440 billion.13 And inevitably, the capital is flowing West. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Europe totaled $12.6 billion (€9.6 billion) in 2012.14 In 2011, for the first time, more Chinese companies than U.S. companies invested in business locations in Germany, and by a significant number: 158 compared to 110.15 This would have been inconceivable twenty years ago.

Red Lights, Green Lights: The Geely Story

“There is nothing mysterious about making cars…I am determined to do this, even at the risk of losing everything I have.”

—Li Shufu, Chair, Geely Automobile Holdings Limited, 1997

China's largest private car manufacturer is in many ways the very model of Globalization 2.0. The company's rapid rise from humble beginnings culminated in its takeover of Volvo in March 2010.

The Volvo deal is a sign of the economic power shift from West to East. As if to underline this, Geely bought Sweden's most recognizable auto-brand from none other than American icon Ford—the very first company to mass-produce affordable cars. What's more, it did so at a bargain price: Ford paid $6.65 billion to acquire Volvo in 1999, while Geely paid Ford a mere $1.8 billion.

Geely's Chair, Li Shufu, had courted Volvo for three years, a determination he demonstrated many times over before Geely's meteoric rise. For example, in what has become a well-known story, when Li graduated school, he invested the money he received as a graduation gift in an old camera and bike. Then, he ...