![]()

PART 1

A Case for Change

BEFORE ONE EMBARKS on a complex journey, it is fair to ask the simple questions: Why not just stay put? What is wrong with the status quo, and how much will really be gained by stepping forward onto this difficult road? After all, it is human nature to cling to the comfort of what is known and resist the challenges and uncertainty of what might lie ahead. The more risky the traveler perceives the journey to be, the more likely that he or she will not venture far from home—which means never reaching the intended destination.

Chapter 1 makes clear the basic reason that there no longer remains much choice but to venture ahead. It describes how today’s environment of uncertainty and change is undermining many corporations’ and institutions’ ability to succeed. It explains why merely tweaking what they do now is no longer an option; why sustaining business excellence will take adopting a different focus to better anticipate and more effectively respond to this growing challenge.

Chapter 2 describes the rationale and foundation for making a case for this change to the leadership, employees, and key stakeholders. It describes a new approach for identifying “value,” and assessing how well a business or an institution is suited to delivering strong, consistent value across the range of conditions it might face. This is an important step to fostering the understanding, buy-in, and sense of excitement that is critical yet very often neglected.

Chapter 3 concludes this part by examining the road ahead for those beginning their lean journey. It describes the five levels of lean maturity and the reasons why firms often stagnate along the way. Finally, it shows that advancing in lean maturity requires a vision, structure, and specific techniques for overcoming the potential to stagnate.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Redefining the Competitive Solution

“WE’RE HERE TODAY because we made mistakes,” CEO Rick Wagoner said to the congressional committee. “And because some forces beyond our control have pushed us to the brink.”1

With this simple statement, the leader of General Motors—once the world’s most powerful manufacturer—essentially acknowledged defeat. The company found itself on the edge of disaster; it could remain afloat only if Congress agreed to give it tens of billions of dollars in taxpayer-funded bailouts—and even then its survival was anything but assured.

How could this titan of manufacturing have plunged into such crisis? Sure, the economy had suffered its worst decline in nearly a century. And with it, customers had simply stopped buying. Yet congressional critics addressed Wagoner and his counterparts at Ford and Chrysler with the same criticism voiced by many observers—that before this downturn, Detroit had been in a steady decline for several decades. Now this once dominant corporation—along with much of this country’s automotive industry—teetered at the brink of extinction.

What went wrong with GM and so many other corporations? Have America’s businesses become soft, unable to see the inefficiencies and waste that crept into their operations? Is their challenge as clear as many describe: Find a way to stretch their business further—demand more from workers, speed up processes, apply greater information technology, or outsource more work to lower wage regions? Does the secret to sustaining competitive advantage boil down to finding a better way of cutting costs?

Like so many of America’s other once mighty corporations, it appears that GM had simply fallen victim to its own success. For decades, the company’s unquestioned market leadership gave it little reason to really change. Despite valiant efforts aimed at cutting costs and refining its methods, it seems that the company did so within the confines of its traditional framework for doing business—an approach that proved to be not nearly enough.

The unfortunate reality is that the environment in which this company must operate today looks dramatically different from the one for which its business practices were built nearly a century ago. Despite all the rationalization and finger pointing, this basic disconnect has significantly contributed to its long, dramatic decline. And this is the same challenge that so many of this nation’s corporations and institutions face as well.

Seeing Beyond Stability

GM’s way of doing business traces back to its historic quest early last century to achieve the unthinkable. In 1921 the company’s newly appointed president, Alfred Sloan, set out to break Henry Ford’s iron-clad lock on the automotive industry—one that he held for nearly two decades. Sloan recognized that the enormous efficiencies Ford’s methods generated made competing head-to-head based on low pricing a losing proposition. So Sloan pointed his company in a very different direction—restructuring for a business environment that he sensed had undergone a substantial shift.

With automobiles becoming widely available, Sloan recognized that customers no longer sought rock-bottom pricing as their only consideration. He built a system that moved beyond Ford’s approach of driving down costs by producing huge quantities of nearly identical vehicles. As described in Going Lean, Sloan instead set out to promote a “mass-class” market, which encouraged more people to buy better and better cars—something that Ford’s way of doing business was ill-suited to support.2

GM succeeded in bringing variety and choice within reach of its customers, moving beyond Ford’s presumption of a single product mass market in favor of a strategy of variety. With five lines of vehicles, its offerings could meet a broad range of customer needs and financial capabilities. This strategy succeeded; it ultimately launched GM to dominate what became the largest manufacturing industry in the world.

Sloan managed his company by operating under what he called coordinated control of decentralized operations.3 This meant that the company’s different divisions operated as separate, distinct organizations—designing and producing different lines of vehicles while generating economies of scale through many of their shared resources. But with it came a new burden: the challenge of managing the incredible complexity this created. He needed a way to simplify the problem—to look at each part of the business in the same way, but while preserving the distinct character of each division that would drive his strategy’s success.

What he came up with was a means to track performance by smoothing out short-term fluctuations, essentially measuring based on average production levels, something he called standard volume.4 This greatly simplified oversight, making it easier to relate costs to their driving factors and determine where greater attention was needed, such as where to focus to maximize workforce, inventory, and equipment efficiencies and which managers were performing well relative to forecasted expectations.

It also made it possible to structure the business in a way that gave managers the insights they needed for maintaining efficient use of people, facilities, and equipment without tracking the myriad of details that had made Henry Ford’s methods so complex. Managers no longer focused on the individual details of work as products progressed down the line. Instead, they set their sights on optimizing factories for the averages, which meant turning out huge batches of identical items at a rate that approximated standard volumes. The downside was that efficiencies dropped off precipitously if they had to operate outside of their intended production conditions.

For a long time, this same basic management system thrived; its underlying presumption of steady, predictable demand seemed to closely match the reality of prevailing business conditions. Industries of all types embraced it as the gold standard for managing complex businesses. Today, however, its limitations are becoming increasingly clear, causing an effect that has become quite serious.

To understand why, let us look to an analogous situation that most readers recently experienced in their own lives. The summer of 2008 brought with it a challenge that many people had never before experienced. Gasoline prices rapidly increased, rocketing beyond the dreaded $3-per-gallon threshold and quickly exceeding $4 per gallon. The impact was immediate and crippling, with people everywhere struggling to pay what had become exorbitant amounts simply to fuel their cars.

Americans faced a growing crisis. But what was the cause? Surprisingly, as clear as it seemed, the issue was not simply the high price at the pump. Instead, unaffordable gasoline was merely the visible symptom of a much deeper issue—a dangerous condition that had been quietly developing for years.

The “Steady-State” Trap

Many years ago I began a weekly routine of fueling my car in preparation for my drive to work on the days ahead. I clearly recall the price. Gasoline cost somewhere around a dollar and a quarter per gallon. More than two decades later I distinctly remember noting that not much had changed; the price of gasoline still fell within the dollar-something range.

The presumption of such steady fuel prices factored heavily into the choices I made (not necessarily consciously)—just as it seemed to for many others. The result was significant and widespread: suburbs grew rapidly, as did the size of the typical vehicle. Americans’ average daily commute increased substantially, while trucks and SUVs increasingly filled the highways. It is not hard to see why Americans broke record after record for their consumption of huge quantities of low-cost gasoline. And in doing so, people everywhere locked themselves into lifestyles that were increasingly dependent on continued price stability.

And then everything changed.

When gasoline prices suddenly spiked, most people could do little to change. They still had to drive to work, and they still had to take care of the many obligations that depended on their use of gasoline. The difference was that fuel was no longer inexpensive; drivers everywhere suddenly had to make tough choices in response to their ever-tightening financial circumstances. And the result soon spread to the broader economy.

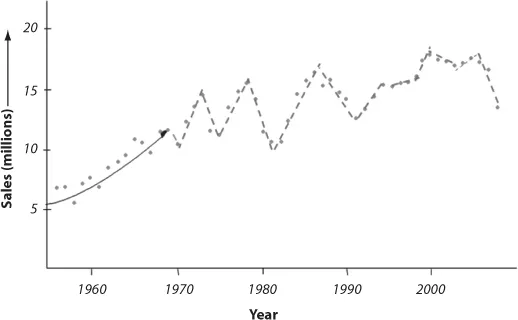

America’s corporations face much the same challenge. Consider the sales trend in the automotive industry, depicted in Figure 1-1. The left side of the graph depicts a smooth and predictable demand pattern in the years following World War II (shown in terms of overall sales)—precisely the environment for which Sloan’s system of management was intended. And for decades, this environment persisted; businesses and institutions everywhere came to operate well within a remarkably narrow range of largely predictable conditions.

Figure 1-1. Automotive Industry Demand Shift

Data Source: Sales from 1965 to 2008: Ward’s Motor Vehicles Facts & Figures 2009, a publication of Ward’s Automotive Group, Southfield, MI USA.

Sales for 1956 to 1964: MVMA Motor Vehicle Facts & Figures, Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Association of the United States, Inc.5

In the early 1970s, the environment abruptly shifted. Unpredictability skyrocketed; customers’ interests began to shift. Businesses that had structured themselves based on a presumption of stability—operating at or near narrowly optimized rates to create great economies of scale to meet precisely forecasted customer needs—suddenly found themselves locked into a way of doing business that was ill-suited for these very different conditions. And each new bout of disruption brought with it the same result: workarounds, disruption, and crisis.

What is particularly striking is how closely this shift correlates to the timeframe in which Detroit’s reputation—along with its market share—began its steep decline. This should have served as a wake-up call for the challenges American producers would face. Yet rather than making a fundamental change to accommodate these dramatically different conditions, they redoubled efforts to stretch their existing product focus and practices a little further—and in doing so achieved the same basic result.

Why does this create such a problem? Going Lean described that such unstable conditions cause substantial internal variation—deviations from intended plans, objectives, or outcomes within traditionally managed organizations built for stability. Variation leads to operational unpredictability, driving the need for workarounds, inventories, and other buffers—waste that draws corporate resources without contributing to creating customer value.

Key Point: What Is Waste?

The late Taiichi Ohno, a recognized architect of the famed Toyota Production System, identified seven forms of waste—excesses that do not add value but draw resources, attention, and create delay and overreaction that promotes more waste.6

1. Overproduction is caused when manufacturers build large quantities of items to maximize economies of scale or build large inventories to buffer against uncertain or changing demands.

2. Waiting is a frequent result of shortages, equipment failures, or other causes of delay from a system suffering the disruptive effects of operational discontinuities.

3. Transportation is one of the more visible forms of waste, including long travel distances that create the potential for delay and the need to handle material several times during delivery or receipt.

4. Processing waste includes extra steps that can creep in over time in dealing with recurring challenges like defects, shortages, and delays due to lagging, disconnected work, or flawed information.

5. Inventory waste is most apparent when manufacturers maintain large quantities of either end items or work-in-progress as a way to bridge value-creating activities whose flow is otherwise disconnected or uncertain.

6. Motion that takes time but does not contribute to the result is wasteful, such as workers searching for tools or “chasing parts” to prevent stoppages from stock-outs.

7. Defects are wasteful on multiple levels. They must be corrected, distracting from operations and causing work that does not create value. Removal of defective parts can cause material shortages on a production line, leading to several other forms of waste (waiting, transportation, motion). Frequent defects create uncertainty, which drives an increase in inventory, another form of waste.

Removing these excesses has become a primary target of today’s cost-conscious managers. Yet wast...