![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Circuits of Capital

(Chapters 1–3 of Volume II)

Capitalists typically start the day with a given amount of money. They go into the marketplace and buy means of production and labor-power, which they put to work using a particular technology and organizational form to produce a new commodity. This commodity is then taken to market and sold for the initial amount of money plus a profit (or, as Marx prefers to call it, a surplus-value). This is the basic form of the circulation of capital that Marx works with in Volume I of Capital. Put schematically, capital is defined as value in motion: Money—Commodities……Production……Commodity’—Money’ (where M' can also be represented as M + DM, or in these chapters as m, the surplus-value). The central thesis Marx works with is that labor has the capacity to create more value (a surplus-value) than the value it can command as a commodity on the market. The freshly produced commodity, “impregnated” with surplus-value, is what is sold for a profit on the market. The reproduction of capital then depends on the recycling of all or part of M' back into the purchase, once more, of labor power and means of production to engage in a fresh round of commodity production.

“In Volume I,” Marx writes, “the first and third stages [M-C and C'-M'] were discussed only insofar as this was necessary for the understanding of the second stage, the capitalist production process. Thus the different forms with which capital clothes itself in its different stages, alternately assuming them and casting them aside, remained uninvestigated. These will now be the immediate object of our enquiry” (109).

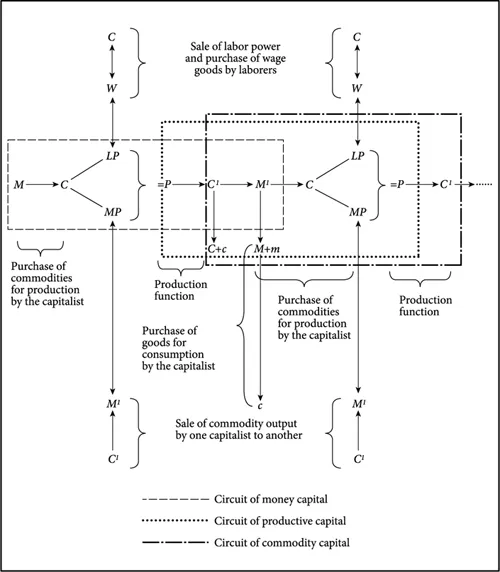

In the first three chapters of Volume II, Marx disaggregates the circulation process into three separate but intertwined circuits of money capital, productive capital and commodity capital. In the fourth chapter, he examines the circuit of what he calls “industrial capital,” which is the unity of the three different circulation processes taken as a whole. In effect, Marx looks at the circulation process from the three different perspectives of money, production and the commodity. The general framework is laid out in Figure 2.

Figure 2

On the surface, this whole approach appears rather simplistic, even banal. He takes the continuous flow of circulation and boxes off three different circulation processes within it. It hardly seems worthwhile. But, through this tactic, he reveals and dissects the difficulties and contradictions inherent within the logic of the circulation process. From each window or perspective we get to see a rather different reality, and this allows us to identify points of potential disruption.

Throughout these chapters, Marx is preoccupied with three things, two of which are very explicit, while the third is implicit. The first is the idea of metamorphosis. This language derives from Volume I, chapter 3, where Marx makes much of the “metamorphoses” that occur within what he calls the “social metabolism” of capital. Metamorphoses are about changes in the form that capital assumes—from money to productive activity to commodity. Marx is interested both in the character that capital assumes as it enters and for a while dwells in each of these different states, and in how capital moves from one state to another. The central question that he poses is: What different possibilities and capacities attach to these different forms, and what difficulties arise in the move from one form to another? The analogy that might help here is that of the lifecycle of the butterfly. It lays its eggs; these become caterpillars that crawl around looking for food, before becoming a chrysalis within a protective cocoon. A beautiful butterfly suddenly emerges from the cocoon, and the butterfly flits around at will before laying its eggs to initiate the cycle anew. In each state the organism exhibits different capacities and powers: as an egg or as a chrysalis, it is immobile but growing; as a caterpillar it crawls around in search of food; and as a butterfly it can flit around at will. And so it is with capital. In its money state, capital can flit around butterfly-like pretty much at will. In its commodity form, capital, like the caterpillar, wanders the earth in search of someone who wants, needs or desires it, and has the money to pay for it and ultimately consume it. As a labor process, capital is for the most part rooted in the “hidden abode of production” (as Marx calls it in Volume I), in the place of the material activity of transforming natural elements through the production of commodities. It is usually locked in place at least during the time taken to make the commodity (transport, as we shall see, is an important exception).

For me, these distinctions are immediately meaningful. The differential spatial and geographical mobilities of capital in these different states have enormous implications for understanding the processes we now lump together under the heading of “globalization.” Each “moment” in the circulation process—money, productive activity, commodity—is expressive of different possibilities. Money is the most geographically mobile form of capital, the commodity somewhat less so, while production processes are generally much harder (though by no means impossible) to move around. Within this general characterization there is a lot of variability. Some forms of commodity are easier to move around than others, and ease of movement is also relative to transportation capacities (containerization made shipping bottled water from France or Fiji to the US possible). The differential empowerment of the different factions of capital has huge consequences for how capital operates on the world stage. To empower finance capital relative to other forms of capital (such as production and merchant capital) is to invite the sort of hypermobility and “flitting around” of capital that has characterized capitalism over the last few decades. Marx does not take up such topics, but there is no reason why we cannot. Marx concentrates on other features of the metamorphoses that occur, and the differences and contradictions that can potentially arise.

This leads to the second major question in which Marx is interested. This concerns the potential for disruptions and crises within the circulatory process itself. In Volume I he made clear that the transitions from one moment to another are never free of tensions. It is generally easier to go, for example, from the universal form of value (money) into the particular form of value (the commodity) than it is to go in the other direction (commodities may be “in love with money,” but “the course of true love never did run smooth,” he observes). There is also no immediate necessity that impels anyone who has sold to use the money they receive to buy. Individuals can hold or hoard money. This underpins Marx’s scathing attack upon Say’s law in Volume I. Say held that purchases and sales are always in equilibrium, and therefore that there can never be any general crisis of overproduction (a proposition that Ricardo also accepted). But the holding of money (hoarding), as Keynes was later also to point out, is a permanent temptation, given that money is a universal form of social power appropriable by private persons. Hoarding is also, Marx shows, socially necessary (and throughout Volume II we will find frequent instances where this is so). But if everyone holds money and no one buys, then the circulation process gums up and eventually collapses. “These forms therefore imply,” says Marx in Volume I, “the possibility of crises, though no more than the possibility. For the development of this possibility into a reality a whole series of conditions are required, which do not yet even exist from the standpoint of the simple circulation of commodities” (C1, 209). Volume II is in part concerned to show how these possibilities might be realized, though it does so in a frustratingly muted and technical way.

Marx also pointed out in Volume I that autonomously forming monetary crises are a very real possibility. With the quantity and prices of commodities constantly shifting, ways have to be found to adjust the supply of money to accommodate to the volatility in commodity production. Here a hoard of money becomes absolutely necessary. It provides a reserve of money to be drawn upon at times of hyperactivity. When money becomes money of account, then the need for commodity money (gold and silver) can be evaded. Balances can be settled up at, say, the end of the year, thereby reducing the demand for actual money (specie, coins, notes). But using money of account creates a new relationship, that between debtor and creditor. And this produces, Marx argued in Volume I, a contradiction, an antagonism, that

bursts forth in that aspect of an industrial and commercial crisis which is known as a monetary crisis. Such a crisis occurs only where the ongoing chain of payments has been fully developed, along with an artificial system for settling them. Whenever there is a general disturbance of the mechanism, no matter what its cause, money suddenly and immediately changes over from its merely nominal shape, money of account, into hard cash. Profane commodities can no longer replace it. (C1, 236)

In other words, you cannot settle your bills with more IOUs; you have got to find hard cash, the universal equivalent and representation of value, to pay them off. If hard cash cannot be found, then

the use-value of commodities becomes valueless, and their value vanishes in the face of their own form of value. The bourgeois, drunk with prosperity and arrogantly certain of himself, has just declared that money is a purely imaginary creation. “Commodities alone are money,” he said. But now the opposite cry resounds over the markets of the world: only money is a commodity. As the hart pants after fresh water, so pants his soul after money, the only wealth. In a crisis, the antithesis between commodities and their value-form, money, is raised to the level of an absolute contradiction. (C1, 236–7)

Does the analysis in Volume II shed light on this issue? The answer is both yes and no. In Volume II, Marx lays the basis for understanding the conditions that might convert the possibilities of circulatory crises into realities. But there is no compelling argument proffered as to why such possibilities must rather than might become realities, and under what conditions. In part, this derives from Marx’s reluctance to integrate the particularities of distribution into his arguments. Marx refrains from any analysis of the role of credit in Volume II, because it is a fact of distribution and a particularity. But it becomes plain as a pikestaff, throughout Volume II, that credit has major effects within the generality of production, and therefore on the actual laws of motion of capital. In the absence of any consideration of how the particularities of distribution and exchange work, a general theory of crisis formation seems a non-starter.

The third and more implicit question that arises in these chapters concerns the definition of the “essence” of capital itself. I am not sure that the term “essence” is right here, but I think these chapters do offer the possibility of reflecting on the different forms that capital can assume, and ask if there is any priority to be given to any one of the forms, as opposed to saying that capital is simply “value in motion” or the total circulation laid out in Figure 2, and that is that. Is one of the circuits of capital more important than the others even though none of them can exist without the others? We need to pay attention to these questions here, because they have deep political implications. But Marx himself makes no attempt to tease out these political meanings. That is something we have to do.

The first link (metamorphosis) in the chain of exchanges that make up capital circulation is the use of money to purchase labor-power and means of production. Money capital here “appears as the form in which capital is advanced.” The word “appears” suggests, as is often the case, that all is not exactly as it seems. “As money capital, [money] exists in a state in which it can perform monetary functions, in the present case of general means of purchase and payment.… Money capital does not possess this capacity because it is capital, but because it is money.” Not all money is capital, and not all buying and selling, even of labor-power (such as in the case of personal services or home help), is caught up in the circulation and accumulation of capital. What converts money functions into money capital “is their specific role in the movement of capital,” and this depends on their relationship to “the other stages of the capital circuit.” Only when embedded in the total circulation process of capital does money function as capital. Then, and only then, does money become “a form of appearance of capital” (113). So there is money, and then money functioning as capital. The two are not the same.

When money is used to buy labor-power—M-LP—then the money actually drops out of the circulation of capital, even as laborers use their money wages to buy commodities that they, under the control of capitalists, have produced. The laborers give up their commodity (labor-power) in order to get the money to buy the commodities they need to live, thus returning money to the circulation of capital. They live in a C-M-C–type circuit (or, as Marx prefers to notate it, an L-M-C circuit), as opposed to the M-C-M' circuit of capital. In this L-M-C movement, Marx argues, “the capital character vanishes though its money character remains” (112). He later expands on this theme:

The wage labourer lives only from the sale of his labour-power. Its maintenance—his own maintenance—requires daily consumption. His payment must therefore be constantly repeated at short intervals … Hence the money capitalist must constantly confront him as money capitalist, and his capital as money capital. On the other hand, however, in order that the mass of direct producers, the wage labourers, may perform the act L-M-C [where L is the sale of their labor power], they must constantly encounter the necessary means of subsistence in purchasable form, i.e. in the form of commodities. Thus this situation in itself demands a high degree of circulation of products as commodities, i.e. commodity production on a large scale. (119)

The movement M-LP is often, and in Marx’s view erroneously, viewed as “the characteristic moment of the transformation of capital into productive capital,” and therefore “as characteristic of the capitalist mode of production.” But “money appears very early on as a buyer of so-called services, without its being transformed into money capital, and without any general revolution in the general character of the economy” (114). For capital circulation truly to begin requires that labor-power first appear upon the market as a commodity. “What is characteristic is not that the commodity labour-power can be bought, but the fact that labour-power appears as a commodity.” Money can be spent as capital “only because labour-power is found in a state of separation from its means of production,” and because the owner of means of production is in a position to take

control of the continuous flow of labour-power, a flow which by no means has to stop when the amount of labour necessary to reproduce the price of labour-power has been performed. The capital relation arises only in the production process because it exists implicitly in the act of circulation, in the basically different economic conditions in which buyer and seller confront one another, in their class relation. It is not the nature of money that gives rise to this relation; it is rather the existence of the relation that can transform the mere function of money into a function of capital. (115)

So here, then, is the first major precondition for the circulation of capital to occur: “The class relation between capitalist and wage-labourer is … already present” (115; emphasis added). This was a major theme in Volume I, particularly in the sections on primitive accumulation. Marx here reiterates that the existenc...