eBook - ePub

The American Crucible

Slavery, Emancipation and Human Rights

Robin Blackburn

This is a test

Share book

- 520 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The American Crucible

Slavery, Emancipation and Human Rights

Robin Blackburn

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

For over three centuries, slavery in the Americas fuelled the growth of capitalism. But the stirrings of a revolutionary age in the late eighteenth century challenged this "peculiar institution" and set the scene for great acts of emancipation in Haiti in 1804, in the United States in the 1860s and Brazil in the 1880s. Blackburn argues that the anti-slavery movement helped forge the political and social ideals we live by today.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The American Crucible an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The American Crucible by Robin Blackburn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia de Norteamérica

Introduction: Slavery and the West

The conquest and colonization of the New World by the early modern European states was a decisive step in the global ‘rise of the West’. The gold and silver which obsessed the conquistadors were just a beginning. America was vast and fertile, and its peoples had domesticated and developed a tempting array of foodstuffs and intoxicants. European traders and colonial officials were able to throw the rich produce of the American cornucopia into what was now – for the first time – a truly global balance of exchanges. Great toil was required to wrest precious metals from the earth, to construct fortified imperial lines of communication, and to cultivate and process such premium products as sugar and tobacco, cotton and indigo. The European conquerors and settlers soon learned how to reinforce and multiply their own efforts by introducing African captives, and using them to strengthen empire and boost the output of the coveted export staples. These processes had their roots in Europe’s own needs and desires, and in the emergence of a new political economy – a new type of state, a new class of merchant and a new type of producer and consumer. The Absolutist state and the early capitalist economy drove a process of imperial and commercial expansion which soon overstretched the labour power available to it. The introduction of millions of Africans, and their subjection to a hugely demanding regime of racialized slavery, was seized upon as the solution to the problem. Between 1500 and 1820 African migrants to the New World outnumbered European migrants by four to one.

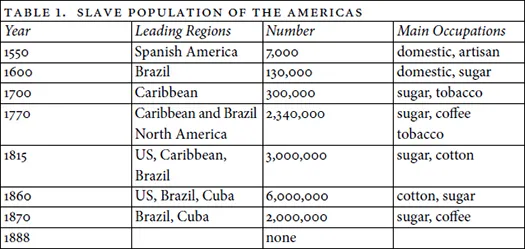

The Atlantic slave trade and the slave systems it served met resistance from the captives and troubled a few observers, but aroused no public controversy until the last decades of the eighteenth century. During the first century or so after Cortés’s arrival, the conquest and enslavement of native peoples, with its tens of millions of victims, constituted one of the great disasters of human history: the number of victims is exceeded only by the total losses of the Second World War. The ‘destruction of the Indies’ eventually aroused widespread condemnation and, as we shall see in the first chapter, led the Spanish royal authorities to discourage the outright enslavement of the indigenous population. Unfortunately, around the same time, they also licensed a trade in African captives to the New World. At first the sorts of work to which the slaves were put were various. They were domestics, gardeners, masons, carpenters, peddlers, and hairdressers, and some eventually managed to purchase their manumission. But this ‘traditional’ Mediterranean pattern of slavery gradually gave way to a new type of enterprise, the plantation, which was based on a great intensification of slave work and slave subjection. This institution was to have a career of nearly three centuries during which it was responsible for an extraordinary boom in output, and eventually for great changes in the power and prosperity of the West in relation to the rest of the world.

The present work considers the entire history of the enslavement of Africans and their descendants in the Americas, from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, explaining why Europeans resorted to slavery and gave it a strongly racialized character. The book also explores the role of resistance and rebellion, abolitionism and class struggle, in the acts of emancipation which finally destroyed the New World slave systems from the 1780s to the 1880s. Slavery and abolition possess their own bibliographies, and are treated as almost separate fields of study. In previous books I have tried to close the gap. But the titles of those books – The Making of New World Slavery and The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery – show them to have a different focus. The temporal span of the present book is also much wider, since it includes the rise and fall of the new slave regimes of the nineteenth-century United States, Brazil and Cuba. The antebellum US South is sometimes taken to typify the slave order of the Americas but, despite some real parallels, it was very distinctive. The slave regimes were by-products, I will argue, of the rise of colonialism and capitalism, making it all the stranger that the ending of colonialism gave a further boost to slavery. The two leading slave powers of the nineteenth century, the United States and Brazil, had thrown off colonial rule and, together with the anomalous colony of Cuba, gave the slave systems a new lease of life.

Those interested in New World slavery and abolition are fortunate in having two recent overall studies by outstanding scholars upon these topics: Inhuman Bondage, by David Brion Davis, and Abolition by Seymour Drescher.1 Like others working in this field, I have a great debt to these two writers. So why the need for another book? The topic is certainly large and complex enough to warrant a variety of approaches.

I focus more attention than Drescher on the plantations, on the consumer capitalism that summoned them into existence and how their extraordinary growth precipitated crisis and provoked slave resistance and nurtured planter rebellion. Whereas I argue that a series of sharp clashes linked to war, revolution and class struggle set the scene for anti-slavery and emancipation in the Americas, Drescher believes that revolutionary excesses led anti-slavery astray, and emphasizes the reformist and parliamentary path to emancipation; however, I believe that he is right to depict a fateful link between abolitionism and the emergence of a new ‘public opinion’.

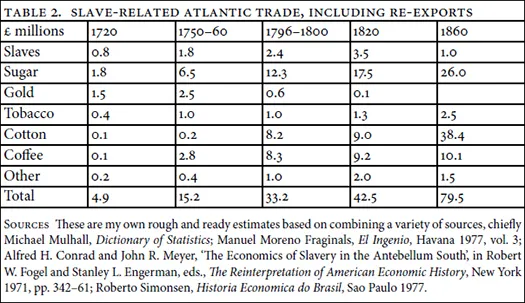

David Brion Davis has written a brilliant study of The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (1975) which, rightly in my view, situates British abolitionism in the context of the Revolutionary age. In his recent book he has more on how slavery worked on the ground – in the plantations – than Drescher. However, Davis devotes less space than I do to slavery and anti-slavery in the Iberian world. Another difference in emphasis relates to the economic significance of slavery. I believe that the slave-based commerce of the Atlantic zone made a large contribution to industrialization, furnishing capital, markets and raw materials, tempting consumers with new drugs and stimulants, and adapting to the ‘steam age’ with remarkable facility. Davis offers a mixed verdict, as when he writes: ‘the expansion of the slave plantation system … contributed significantly to Europe’s, and also America’s economic growth. But economic historians have wholly disproved the narrower proposition that the slave trade or even the plantation system as a whole created a major share of the capital that financed the Industrial Revolution.’2 In Chapter 4 I offer evidence for reaching a stronger conclusion than this.

While Drescher has rightly resisted interpretations of abolition that reduce it to economic interest, I argue that abolitionist movements were intimately linked to the stresses and strains of the industrial revolution.

I shamelessly borrow from these authors where I believe that they have got it right, but my concern is with what was newly forged in the crucible of the Americas, whether it was a more intensely racialized slavery or a reformulated ‘rights of man’. My emphasis throughout is on how slavery and abolition in the Americas as a whole were linked to the overall evolution of society, culture and economy in and beyond the Atlantic world – to the functioning of the European monarchies, to the differences between Protestant and Catholic, Iberian and Anglo-Dutch colonialism, to the rise of capitalism, to the succession of revolutions on both sides of the Atlantic, to the colonial racial order and what followed, to industrialization and the logic of Great Power rivalry, and to the emergence of new social values and social rights in the African diaspora and in momentous national and class struggles. (I would have liked to offer a fuller account of the tremendous impact on Africa of the Atlantic slave trade, but that will have to remain a task for another time.)

For nearly 400 years, struggles over slavery were of the greatest importance in the Atlantic region and yet they take place, as it were, offstage. The award to Britain of the asiento – the right to supply slaves to South America – by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1714 was one of the rare occasions when it might seem that the Great Powers took some notice; but even this was misleading, since the main story at that time was the hugely larger – and minimally regulated – trade in slaves to the English and French colonies, and to Portuguese Brazil. In my view the emergence and growth of capitalism was very much part of the problem, and not, as some recent accounts would have it, part of the solution. The destruction of slavery, like its initial spread and growth, was a by-product of such central events in the Atlantic world as the American and French Revolutions, British industrialization, the Napoleonic Wars, the Spanish American revolutions, the US Civil War, the rise and fall of the Brazilian Empire, and Cuba’s protracted struggle for independence.

The possibility of assessing the contribution of Atlantic history to world history has been greatly boosted by the advance of research and by debates over which models best explain the pattern of events, especially since it is only recently that research had established such basic information as the size of the Atlantic slave trade. There is still unevenness in the literature available on slavery and abolition in the different regions of the New World – but a wave of recent publications, many in Spanish, French and Portuguese, is beginning to change this and assisted me in broadening my account.

The advance of abolition has been central to national historiography in the Atlantic world, and it has typically been couched in celebratory mode. Important protagonists of this history were often neglected, and the sometimes bitter fruits of emancipation were ignored. Descendants of slaves – among them W. E. B. Du Bois, C. L. R. James and Eric Williams – have made a major contribution to supplying a more balanced assessment. In The American Crucible I seek to evaluate the controversies their work has aroused. Because of the size and value of the slave systems, and because of conflicts over the future of slavery, the New World became a crucible of new nations, values, institutions and identities. The clashes generated by racial slavery, and the new complexities of commercial and industrial capitalism, gave birth to an age of revolutions and rival conceptions of modernity. While general histories have rightly studied the novel aspirations fostered by the American and French Revolutions, they have too often failed properly to register the contribution of Haiti and Spanish America in extending and re-working the doctrine of the ‘rights of man and of the citizen’. African agency and the counterculture of the freed people helped to shape emancipation in major ways, in a pattern that crisscrossed the Atlantic. At the limit, as I hope to show, the new class struggles of the industrial-plantation order put in question the prevailing forms of racial domination and capital accumulation. Unfortunately the achievements of emancipation were limited, checked or even reversed by the weaknesses and divisions of the anti-slavery movements when they were put to the test of success. Racial oppression and inequality took new forms. However, such outcomes were contested, as we will see, and thus contributed to reshaping political programmes and the appeal to basic rights.

The role of both slave revolt and natural rights doctrines in the destruction of slavery has given rise to new controversies. João Pedro Marques argues that abolitionism, especially British abolitionism, should be once again given the entire credit for ending New World slavery, and that the contribution of slave resistance and revolt was minimal and has been greatly exaggerated.3 In contrast to the account I offer in this book, Marques insists that the world of abolitionism and that of the Haitian Revolution ‘do not make part of the same series’ since the deliberate action of a parliamentary body is quite distinct from an elemental upsurge of revolt. (However, Marques does make an exception for the revival of British abolitionism in 1804, the year of Haiti’s founding). While Drescher and Marques do not agree on all points they share the view that Haiti made a largely negative contribution – it was a horror story – while British abolition was the real saviour of the enslaved.

The Haitian Revolution suppressed slavery three or four decades before the British managed to do so. Some recent authors have seen this as an early triumph for the idea of the ‘rights of...