![]()

PART I

Retrochic

![]()

Retrofitting

1 The Aesthetics of Light and Space

Forty years ago, when ‘Do-It-Yourself’ first caught on as a national enthusiasm, modernization and home improvement were interchangeable terms, just as ‘ugly’ was commonly coupled with the old-fashioned, and ‘Victorian’ with the out-of-date. The ruling ideology of the day was forward-looking and progressive, the ruling aesthetic one of light and space. Newness was regarded as a good in itself, a guarantee of things that were practical and worked. Modern heating was efficient (‘In…the open fire…only about 17 per cent of the heat finds its way into the room; the rest goes up the chimney’ 1); modern plumbing, as househunters were advised, ‘sound’. The Victorian mansion, though it might be converted into maisonettes or flats was, left to itself, large, draughty and wasteful of space – ‘crumbling, decaying and totally uneconomic,2 was the verdict on those cleared away at Roehampton when the LCC put up its much-admired ‘point-blocks’. The by-law terraced street, with its poky houses and absence of light and space, was ripe for demolition. Like the ‘Dickensian’ tenements and the basement dwelling, it was thought of as a breeding-ground for TB.

In the domestic interior, new materials – man-made fibres especially – were routinely preferred to old. ‘Scientifically up-to-date’ carpets – in the words of the News of the World ‘Better Homes’ book – had rubberized backings to make them moth- and damp-resistant.3 Plastic lavatory seats were more hygienic than wooden ones, which collected germs. Traditional upholstery, ‘with its daily accumulations of dust’,4 was much less serviceable for soft furnishings than Pirelli webbing, fibreglass covering and latex foam rubber – ‘light’, ‘hygienic’ and ‘almost everlastingly resilient’.5 Latex foam was also recommended as a hygienic filling for children’s toys6 and as an alternative to the interior-sprung mattress (‘Latex foam mattresses…do not gather fluff or dust, and can be washed if necessary’7). Candlewick bedspreads were recommended for the same reason: ‘easy washing, no ironing, no trouble’.8

For the handyman (Do-It-Yourself, then, was still regarded as a masculine province) home improvement was largely a matter of making surfaces seamless. Doors were hardboarded to cover up dust-collecting panels and give them a streamlined look. Dados and picture-rails were taken down so that the walls could be painted in one colour: ‘the unbroken surface…will make your room seem much larger’.9 Bathroom pipes were boxed in as unsightly and the bath itself, if the household budget ran to it, replaced by modern ‘non-chippable and rust-proof’ fibreglass, recommended on the grounds of both hygiene and looks. ‘The gleaming, streamlined bathroom is a modern invention…a fine spick-and-span affair…. Bathrooms in old houses can look incredibly dreary.’10 Fireplaces were removed as dust-traps and replaced by convectors or radiators. The cast iron, as Do It Yourself explained to readers in October 1958, could be cracked away with a club hammer:

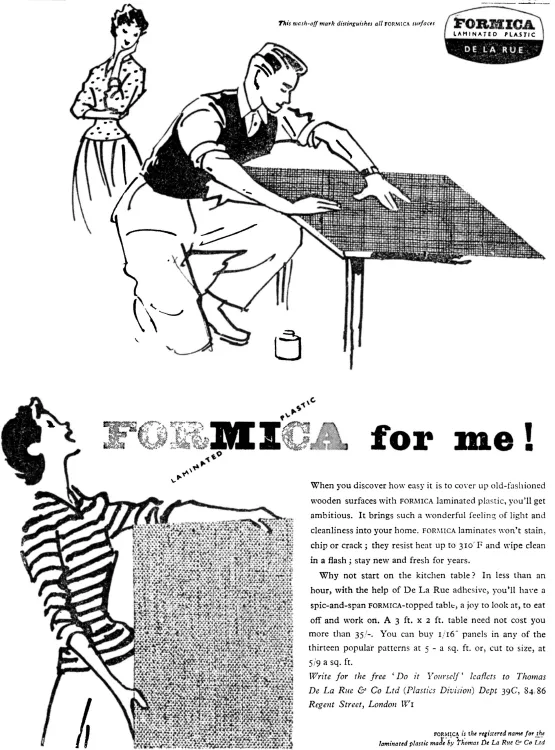

In the kitchen – regarded, in those days, as a menial workplace, and occupying much less space than it does in houses and flats today – the great object of improvement was ‘labour saving’. The News of the World ‘Better Homes’ manual advised ‘gradual modernization’.12 The old-fashioned sink could be replaced by a stainless steel unit. The cupboards could be fitted with ‘flush’ doors. Above all there should be a washable and continuous working surface. Formica – ‘the surface with a smile’ – was vigorously promoted in this way, an easy-to-fit domestic improvement which could transform the housewife’s lot: ‘More leisure, more colour, less work are yours from the day “FORMICA” Laminated Plastic comes into your kitchen. You can do a busy morning’s cooking on a “FORMICA”-topped table – and wipe away every trace, in seconds. The satin-smooth surface thrives on hard work and is impervious to stains or marks.’13

Windows, too, ideally were seamless. Glazing bars were dispensed with to produce a deadpan, streamlined surface which was easily cleanable and maximized the light. ‘The outside coming in’ was one of the architectural ideals of the period. One frequent device was the horizontally pivoted window, framed in metal; another, sliding sheets of glass which could be pushed back into a cavity. ‘The south wall of the living room is…of glass’, runs an admiring report in The Country Life Book of Houses of 1963, ‘the upper part comprising three frameless sheets of glass which slide very sweetly on a brass track.’14 When the replacement window boom began in the early 1960s, it followed a similar pattern. Sash windows were dispensed with, on account of the frequency with which they needed to be repainted and the likelihood that the wood would rot. Metal-framed windows, in steel or aluminium, were much in vogue for the kitchen. Double-glazing units came in seamless sheets of glass; ‘picture windows’ in giant panels.

One of the delights of the handyman of this period was making old furniture look new. Tables could be made to look ‘contemporary’ by taking off their legs and substituting screw-on splays;15 the shabby old dresser could be smartened up with a colourful coat of Robbialac – ‘the quick-drying easy-to-use finish which gives a diamond-hard gleaming surface’16 and the addition of bright plastic handles to the drawers. A little modernizing of this kind could transform the old-fashioned bathroom: ‘A new bath or basin may be too costly for the family budget, but modern fittings, particularly chromium taps, can save a great deal of the housewife’s time and add to the general appearance of the bathroom. Few women have time nowadays to polish brass taps every day.’17 Under influences like this, children’s rooms of the period were given a sunshine look. ‘Old Furniture Made Smart’ is the heading of an article in the ‘Fatherhood’ section of Parents in April 1955:

The early gentrifiers taking up residence (rather nervously) in rundown Victorian terraces, and the architects and developers converting multi-occupied rooming-houses into self-contained flats, acted in a similar spirit when doing up old properties to give them a contemporary look. Interiors were systematically gutted to remove every trace of the past. In large houses suspended ceilings covered up cornices and mouldings; in smaller ones partition walls were removed to give rooms a see-through look. Floors were sanded and sealed to give them a modern feeling, ‘spare yet gay’. ‘Off-white’ here served as the equivalent of the bright colours of the working-class interior, cantilevered shelves as the space-savers. Curtains were dispensed with, in defiance of the English laws of propriety, allowing the light to stream in by day and at night transforming dining-rooms into stage-sets. Furniture was minimalist – futurist pieces, in glass or metal, being regarded as the perfect foil to older surroundings. Lighting was futurist too – fluorescent tubes in the kitchen19 and on the desk a swivel-joint anglepoise lamp with perforated metal reflectors.20 Taps, handles and coat hooks, knives and forks and crockery were all ideally rimless, ‘designed for easy handling and cleaning, with no ridges to collect soap and dirt’.21 If there was an extension at the back of the house – as was often the case when houses in erstwhile industrial terraces were transformed into bijou residences – it might be finished off with floor-to-ceiling glass walls in the form of ‘patio’ sliding doors.

In the property columns of the newspapers, as in the House and Garden interior, modernization, where period properties were concerned, was treated as an absolute good. Roy Brooks, the fashionable left-wing estate agent, whose advertisements in the Sunday Times and the Observer – Jimmy Porter’s ‘posh Sundays’ – were a delight of the cognoscenti, and who has some claim to being a pioneer of gentrification in the scruffier parts of London, treated new gadgetry as a selling-point where period property was at stake – even a Tudor farmhouse was recommended on account of its ‘luxury tiled bathrooms’ and its ‘super kitchen’ with ‘double sink unit’. Here are some representative examples of his style.

One moment to pause on, in any archaeology of changing attitudes to the past, would be the 1951 Festival of Britain. Taking its occasion from the centenary of the Great Exhibition of 1851, it was determinedly modernist in bias, substituting, for the moth-eaten and the traditional, vistas of progressive advance: ‘a great looking forward after years of rationing and greyness’. The past was present only in the form of anachronism. The model of Stephenson’s Rocket which graced the Dome of Discovery was a primitive original of more streamlined successors; the Emmett Railway in the Battersea Pleasure Park, with its whimsical title (‘The Far Tottering and Oyster Creek Railway’) was a phantasmagoria of backwardness, showing that the British had a sense of humour; old-time music-hall, one of the Festival’s evening entertainments, showed that they could let their hair down and engage in ‘knees-up’ frolics. The things that one was expected to admire were the novelties – the bright new towns of the future, represented by the Lansbury estate; the products of industrial design, proudly displayed on the trade stands; the labour-saving kitchen units; the clean lines of ‘functional’ architecture; the gay colours of ‘contemporary’ style. ‘The Homes and Gardens’ pavilion, a major influence on design, was a showcase for the new; as visitors were informed as they entered, it took the past ‘as read’.23

The themes of the festival were amplified by the ‘Do-It-Yourself movement of the 1950s. They were vigorously promoted by the Council of Industrial Design with passionate moderns at its head – first Gordon Russell and then Paul Reilly. They were taken up by go-ahead manufacturers such as Hille, and embraced by avant-garde designers. Enthusiasm for the modern was to a remarkable degree cross-class. Up-market design magazines such as House and Garden embraced it as enthusiastically as those like the News of the World or Odhams Press whose guides were directed at working-class readers. Most striking of all – in the light of its later contributions to conservationism and, as critics complain, the revival of aristocratic fantasy – was the endorse...