- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Cities are the new battleground of our increasingly urban world. From the slums of the global South to the wealthy financial centers of the West, Cities Under Siege traces the spread of political violence through the sites, spaces, infrastructure and symbols of the world's rapidly expanding metropolitan areas.

Drawing on a wealth of original research, Stephen Graham shows how Western militaries and security forces now perceive all urban terrain as a conflict zone inhabited by lurking shadow enemies. Urban inhabitants have become targets that need to be continually tracked, scanned and controlled. Graham examines the transformation of Western armies into high-tech urban counter-insurgency forces. He looks at the militarization and surveillance of international borders, the use of 'security' concerns to suppress democratic dissent, and the enacting of legislation to suspend civilian law. In doing so, he reveals how the New Military Urbanism permeates the entire fabric of urban life, from subway and transport networks hardwired with high-tech 'command and control' systems to the insidious militarization of a popular culture corrupted by the all-pervasive discourse of 'terrorism.'

Drawing on a wealth of original research, Stephen Graham shows how Western militaries and security forces now perceive all urban terrain as a conflict zone inhabited by lurking shadow enemies. Urban inhabitants have become targets that need to be continually tracked, scanned and controlled. Graham examines the transformation of Western armies into high-tech urban counter-insurgency forces. He looks at the militarization and surveillance of international borders, the use of 'security' concerns to suppress democratic dissent, and the enacting of legislation to suspend civilian law. In doing so, he reveals how the New Military Urbanism permeates the entire fabric of urban life, from subway and transport networks hardwired with high-tech 'command and control' systems to the insidious militarization of a popular culture corrupted by the all-pervasive discourse of 'terrorism.'

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

War Re-enters the City

URBAN PLANET

At the dawn of the twentieth century, one in ten of the Earth’s 1.8 billion people lived in cities – an unprecedented proportion, even though humankind remained overwhelmingly rural and agricultural. A mere fraction of the urban population, overwhelmingly located in the booming metropoles of the global North, orchestrated the industrial, commercial and governmental affairs of an ever more interconnected colonial world. Meanwhile, in the colonized nations, urban populations remained relatively tiny, concentrated in provincial capitals and entrepôts: ‘The urban populations of the British, French, Belgian and Dutch empires at the Edwardian zenith,’ writes Mike Davis, ‘probably didn’t exceed 3 to 5 per cent of colonised humanity’.1 All told, the urban population of the world in 1900 – some 180 million souls – numbered no more than the total population of the world’s ten largest cities in 2007.

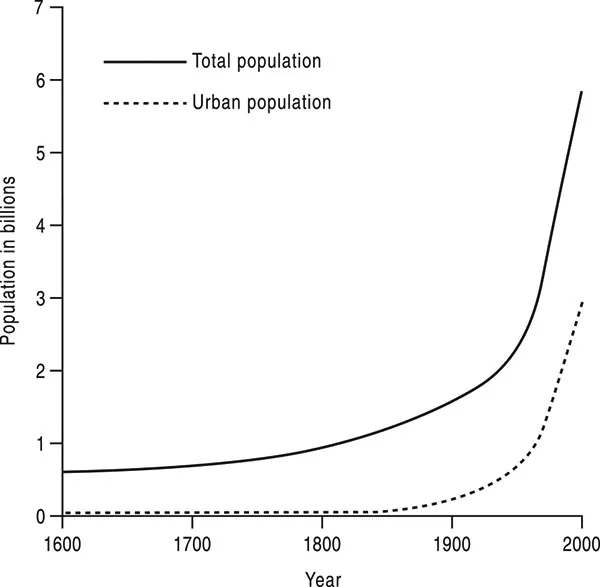

In the course of the next half-century, Earth’s population grew steadily but unspectacularly, reaching 2.3 billion by 1950. While the urban population nearly tripled to over 500 million, it still formed less than 30 per cent of the whole. Developments in the following half-century, however, were astonishing: the greatest mass movement, combined with the greatest burst of demographic growth, in human history. Between 1957 and 2007, the world’s urban population quadrupled. By 2007, half the world’s 6.7 billion people could be classed as city-dwellers (Figure 1.1). Homo sapiens had precipitously become a predominantly urban species. It had taken almost ten thousand years – from 8000 BC to 1960 – for cities to house the world’s first billion urbanites; it will take a mere fifteen for this figure to rise from three billion to four.2 Dhakar, the capital of Bangladesh, a city of 400,000 in 1950, will by 2025 have mushroomed into a metropolitan area of some 22 million – a fiftyfold increase within only seventy-five years (Figure 1.2). Given the density of cities, more than half of humanity is currently squeezed onto just 2.8 per cent of our planet’s land surface, and the squeeze is tightening day by day.3

1.1 Total world population, and total urban population, 1600–2000.

As we move into what has been called the ‘urban century’, there appears to be no end to this headlong urbanization of our world. In 2007, 1.2 million people were added to the world’s urban population each week. By 2025, according to current estimates, there could easily be five billion urbanites, two-thirds of whom will live in ‘developing’ nations. By 2030, Asia alone will have 2.7 billion; the Earth’s cities will be packed with 2 billion more people than they accommodate today. Twenty years further on, by 2050, fully 75 per cent of the world’s estimated 9.2 billion people will most likely be living in cities.4

In other words, within just over four decades the Earth will host seven billion urban dwellers – 4 billion more than in 2007. The overwhelming majority of these will be in the burgeoning cities and megacities of Asia, Africa and Latin America. To be sure, many cities in developed nations will still be growing, but their growth will be dwarfed by urban explosion in the global South.

As demographic, political, economic and perhaps technological centres of gravity emerge in the South, massive demographic and economic shifts will inexorably continue. As recently as 1980, thirteen of the world’s thirty biggest cities were in the ‘developed world’; by 2010, this number will have dwindled to eight. By 2050, it is likely that only a few of the top thirty megacities will be located in the erstwhile ‘developed’ nations (Figure 1.2).

1.2 World’s largest thirty cities in 1980, 1990, 2000 and (projected) 2010. Table illustrates the growing domination of ‘mega-cities’ in the global South.

POLARIZING WORLD

We are now learning what countries across the developing world have experienced over three decades: unstable and inequitable neoliberal economics leads to unacceptable levels of social disruption and hardship that can only be contained by brutal repression.5

The rapid urbanization of the world matters profoundly. As the UN has declared, ‘the way cities expand and organize themselves, both in developed and developing countries, will be critical for humanity.6

While relatively egalitarian cities like those in continental Western Europe tend to foster a sense of security, highly unequal societies are often marked by fear, high levels of crime and violence, and intensifying militarization. The dominance of neoliberal models of governance over the past three decades, combined with the spread of punitive and authoritarian models of policing and social control, has exacerbated urban inequalities. As a result, the urban poor are often confronted with reductions in public services on the one hand, and a palpable demonization and criminalization on the other.

Neoliberalization – the reorganization of societies through the widespread imposition of market relationships – provides today’s dominant, if crisisridden, economic order.7 Within this framework, societies tend to sell off public assets (whether utilities or public spaces) and open up domestic markets to outside capital. Market-based strategies for the distribution of public services undermine and supplant social, health and welfare programmes.8

An extraordinary expansion of financial instruments and speculative mechanisms is also crucial to neoliberalization. Every area of society becomes marketized and financialized. States and consumers alike pile up drastic financial debt, securitized through arcane instruments of global stock markets. By 2006, just before the onset of the global financial crash, financial markets were trading more in a month than the annual gross domestic product of the entire world.9

In practice, the much-vaunted economic axioms of ‘privatization’, ‘structural adjustment’ and the ‘Washington consensus’ camouflage disturbing transformations. They serve as euphemisms for what Gene Ray has called ‘the coordinated coercions of the global debtors’ prison, for the pulverization of local labor and environmental protections, and for the breaking open of all markets to the uncontrolled operations of finance capital’.10 Wealth has been stripped from poor and vulnerable economies through the flagrant predations of global capital, organized from a mere handful of megacities in the North. Structural adjustment policies (SAPs) imposed on the world’s poor nations by the IMF and the World Bank between the late 1970s and the late 1990s re-engineered economies while ignoring issues of social welfare and human security. The result was enormous disruption, widespread insecurity, and massive, informal urbanization. Deteriorating conditions in increasingly marketized agricultural areas – often combined with the mandated withdrawal of welfare systems under the strictures of the SAPs11 – forced many people to migrate to cities.

Invariably, then, ‘liberalization’ has meant a collapse in formal employment opportunities for marginal urban populations; a withering of fiscal, social, and medical safety-nets, public health systems, public utilities, and education services; and a massive growth of both consumer debt and the informal sector of economies. Such fiscal and debt regimes have often tended, as Mike Davis puts it, to ‘strip-mine the public finances of developing countries and throttle new investment in housing and infrastructure.’ SAPs have thus worked in many cases to ‘decimate public employment, destroy import-substitution industries, and displace tens of thousands of rural producers unable to complete against the heavily subsidized agri-capitalism of the rich countries.’12

Such processes have been a key driving force behind the global ratcheting-up of inequality within the past three decades. Across the world, social fissures and extreme polarization – intensified by the global spread of neoliberal capitalism and market fundamentalism – have tended to concentrate most visibly and densely in burgeoning cities. The urban landscape is now populated by a few wealthy individuals, an often precarious middle class, and a mass of outcasts.

Almost everywhere, it seems, wealth, power and resources are becoming ever more concentrated in the hands of the rich and the super-rich, who increasingly sequester themselves within gated urban cocoons and deploy their own private security or paramilitary forces for the tasks of boundary enforcement and access control. ‘In many cities around the world, wealth and poverty coexist in close proximity,’ wrote Anna Tibaijuk, director of the UN’s Habitat Programme, in October 2008. ‘Rich, well-serviced n...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: ‘Target Intercept …’

- 1. War Re-enters the City

- 2. Manichaean Worlds

- 3. The New Military Urbanism

- 4. Ubiquitous Borders

- 5. Robowar Dreams

- 6. Theme Park Archipelago

- 7. Lessons in Urbicide

- 8. Switching Cities Oe

- 9. Car Wars

- 10. Countergeographies

- Illustration Credits and Sources

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cities Under Siege by Stephen Graham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Aménagement urbain et paysager. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.