![]()

PART I

The Great Drought, 1876–1878

![]()

1

Victoria’s Ghosts

The more one hears about this famine, the more one feels that such a hideous record of human suffering and destruction the world has never seen before.

— Florence Nightingale (1877)

“Here’s the northeast monsoon at last,” said Hon. Robert Ellis, C.B., junior member of the Governor’s Council, Madras, as a heavy shower of rain fell at Coonoor, on a day towards the end of October 1876, when the members of the Madras Government were returning from their summer sojourn on the hills.

“I am afraid that is not the monsoon,” said the gentleman to whom the remark was made.

“Not the monsoon?” rejoined Mr. Ellis. “Good God! It must be the monsoon. If it is not, and if the monsoon does not come, there will be an awful famine.”1

The British rulers of Madras had every reason to be apprehensive. The life-giving southwest monsoon had already failed much of southern and central India the previous summer. The Madras Observatory would record only 6.3 inches of precipitation for all of 1876 in contrast to the annual average of 27.6 inches during the previous decade.2 The fate of millions now hung on the timely arrival of generous winter rains. Despite Ellis’s warning, the governor of Madras, Richard Grenville, the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, who was a greenhorn to India and its discontents, sailed away on a leisurely tour of the Andaman Islands, Burma and Ceylon. When he finally reached Colombo, he found urgent cables detailing the grain riots that were sweeping the so-called Ceded Districts of Kurnool, Cuddapah and Bellary in the wake of another monsoon failure. Popular outbursts against impossibly high prices were likewise occurring in the Deccan districts of neighboring Bombay Presidency, especially in Ahmednagar and Sholapur. Having tried to survive on roots while awaiting the rains, multitudes of poor peasants and laborers were now on the move, fleeing a slowly dying countryside.3

As the old-hands at Fort St. George undoubtedly realized, the semi-arid interior of India was primed for disaster. The worsening depression in world trade had been spreading misery and igniting discontent throughout cotton-exporting districts of the Deccan, where in any case forest enclosures and the displacement of gram by cotton had greatly reduced local food security. The traditional system of household and village grain reserves regulated by complex networks of patrimonial obligation had been largely supplanted since the Mutiny by merchant inventories and the cash nexus. Although rice and wheat production in the rest of India (which now included bonanzas of coarse rice from the recently conquered Irawaddy Delta) had been above average for the past three years, much of the surplus had been exported to England.4 Londoners were in effect eating India’s bread. “It seems an anomaly,” wrote a troubled observer, “that, with her famines on hand, India is able to supply food for other parts of the world.”5

Table 1.1

Indian Wheat Exports to the UK, 1875–78

(1,000s of Quarters)

| 1875 | 308 | |

| 1876 | 757 | |

| 1877 | 1,409 | |

| 1878 | 420 | |

Source: Cornelius Walford, The Famines of the World, London 1879, p. 127.

There were other “anomalies.” The newly constructed railroads, lauded as institutional safeguards against famine, were instead used by merchants to ship grain inventories from outlying drought-stricken districts to central depots for hoarding (as well as protection from rioters). Likewise the telegraph ensured that price hikes were coordinated in a thousand towns at once, regardless of local supply trends. Moreover, British antipathy to price control invited anyone who had the money to join in the frenzy of grain speculation. “Besides regular traders,” a British official reported from Meerut in late 1876, “men of all sorts embarked in it who had or could raise any capital; jewelers and cloth dealers pledging their stocks, even their wives’ jewels, to engage in business and import grain.”6 Buckingham, not a free-trade fundamentalist, was appalled by the speed with which modern markets accelerated rather than relieved the famine:

The rise [of prices] was so extraordinary, and the available supply, as compared with well-known requirements, so scanty that merchants and dealers, hopeful of enormous future gains, appeared determined to hold their stocks for some indefinite time and not to part with the article which was becoming of such unwonted value. It was apparent to the Government that facilities for moving grain by the rail were rapidly raising prices everywhere, and that the activity of apparent importation and railway transit, did not indicate any addition to the food stocks of the Presidency … retail trade up-country was almost at standstill. Either prices were asked which were beyond the means of the multitude to pay, or shops remained entirely closed.7

As a result, food prices soared out of the reach of outcaste laborers, displaced weavers, sharecroppers and poor peasants. “The dearth,” as The Nineteenth Century pointed out a few months later, “was one of money and of labour rather than of food.”8 The earlier optimism of mid-Victorian observers—Karl Marx as well as Lord Salisbury—about the velocity of economic transformation in India, especially the railroad revolution, had failed to adequately discount for the fiscal impact of such “modernization.” The taxes that financed the railroads had also crushed the ryots. Their inability to purchase subsistence was further compounded by the depreciation of the rupee due to the new international gold standard (which India had not adopted), which steeply raised the cost of imports. Thanks to the price explosion, the poor began starve to death even in well-watered districts like Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu, “reputed to be immune to food shortages.”9 Sepoys meanwhile encountered increasing difficulty in enforcing order in the panic-stricken bazaars and villages as famine engulfed the vast Deccan plateau. Roadblocks were hastily established to stem the flood of stick-thin country people into Bombay and Poona, while in Madras the police forcibly expelled some 25,000 famine refugees.10

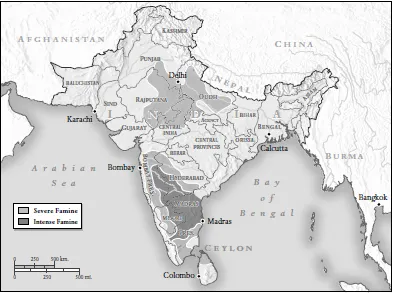

Figure 1.1 India: The Famine of 1876–78

India’s Nero

The central government under the leadership of Queen Victoria’s favorite poet, Lord Lytton, vehemently opposed efforts by Buckingham and some of his district officers to stockpile grain or otherwise interfere with market forces. All through the autumn of 1876, while the vital kharif crop was withering in the fields of southern India, Lytton had been absorbed in organizing the immense Imperial Assemblage in Delhi to proclaim Victoria Empress of India (Kaiser-i-Hind). As The Times’s special correspondent described it, “The Viceroy seemed to have made the tales of Arabian fiction true … nothing was too rich, nothing too costly.” “Lytton put on a spectacle,” adds a biographer of Lord Salisbury (the secretary of state for India), “which achieved the two criteria Salisbury had set him six months earlier, of being ‘gaudy enough to impress the orientals’ … and furthermore a pageant which hid ‘the nakedness of the sword on which we really rely.’”11 Its “climacteric ceremonial” included a week-long feast for 68,000 officials, satraps and maharajas: the most colossal and expensive meal in world history.12 An English journalist later estimated that 100,000 of the Queen-Empress’s subjects starved to death in Madras and Mysore in the course of Lytton’s spectacular durbar.13 Indians in future generations justifiably would remember him as their Nero.14

Figure 1.2 The Poet as Viceroy: Lytton in Calcutta, 1877

Following this triumph, the viceroy seemed to regard the growing famine as a tiresome distraction from the Great Game of preempting Russia in Central Asia by fomenting war with the blameless Sher Ali, the Emir of Afghanistan. Lytton, according to Salisbury, was “burning with anxiety to distinguish himself in a great war.” 15 Serendipitously for him, the Czar was on a collision course with Turkey in the Balkans, and Disraeli and Salisbury were eager to show the Union Jack on the Khyber Pass. Lytton’s warrant, as he was constantly reminded by his chief budgetary adviser, Sir John Strachey, was to ensure that Indian, not English, taxpayers paid the costs of what radical critics later denounced as “a war of deliberately planned aggression.” The depreciation of the rupee made strict parsimony in the nonmilitary budget even more urgent.16

The 44-year-old Lytton, the former minister to Lisbon, had replaced the Earl of Northbrook after the latter had honorably refused to acquiesce in Disraeli’s machiavellian “forward” policy on the northwest frontier. He was a strange and troubling choice (actually, only fourth on Salisbury’s short list) to exercise paramount authority over a starving subcontinent of 250 million people. A writer, seemingly admired only by Victoria, who wrote “vast, stale poems” and ponderous novels under the nom de plume of Owen Meredith, he had been accused of plagiarism by both Swinburne and his own father, Bulwer-Lytton (author of The Last Days of Pompeii).17 Moreover, it was widely suspected that the new viceroy’s judgement was addled by opium and incipient insanity. Since a nervous breakdown in 1868, Lytton had repeatedly exhibited wild swings between megalomania and self-lacerating despair.18

Although his possible psychosis (“Lytton’s mind tends violently to exaggeration” complained Salisbury to Disraeli) was allowed free reign over famine policy, it became a cabinet scandal after he denounced his own government in October 1877 for “allegedly attempting to create an Anglo-Franco-Russian coalition against Germany.” As one of Salisbury’s biographers has emphasized, this was “about as absurd a contention as it was possible to make at the time, even from the distance of Simla,” and it produced an explosion inside Whitehall. “Salisbury explained the Viceroy’s ravings by admitting that he was ‘a little mad’. It was known that both Lytton and his father had used opium, and when Derby read the ‘inconceivable’ memorandum, he concluded that Lytton was dangerous and should resign: ‘When a man inherits insanity from one parent, and limitless conceit from the other, he has a ‘ready-made excuse for almost any extravagance which he may commit.’”19

But in adopting a strict laissez-faire approach to famine, Lytton, demented or not, could claim to be extravagance’s greatest enemy. He clearly conceived himself to be standing on the shoulders of giants, or, at least, the sacerdotal authority of Adam Smith, who a century earlier in the The Wealth of Nations had asserted (vis-à-vis the terrible Bengal drought-famine of 1770) that “famine has never arisen from any other cause but the violence of government attempting, by improper means, to remedy the inconvenience of dearth.”20

Smith’s injunction against state attempts to regulate the price of grain during famine had been taught for years in the East India Company’s famous college at Haileybury.21 Thus the viceroy was only repeating orthodox curriculum when he lectured Buckingham that high prices, by stimulating imports and limiting consumption, were the “natural saviours of the situation.” He issued strict, “semi-theological” orders that “there is be no interference of any kind on the part of Government with the object of reducing the price of food,” and “in his letters home to the India Office and to politicians of both parties, he denounced ‘humanitarian hysterics’.”22 “Let the British public foot the bill for its ‘cheap sentiment,’ if it wished to save life at a cost that would bankrupt India.”23 By official dictate, India like Ireland before it had become a Utilitarian laboratory where millions of lives were wagered against dogmatic faith in omnipotent markets overcoming the “inconvenience of dearth.”24 Grain merchants, in fact, preferred to export a record 6.4 million cwt. of wheat to Europe in 1877–78 rather than relieve starvation in India.25

Lytton, to be fair, probably believed that he was in any case balancing budgets against lives that were already doomed or devalued of any civilized human quality. The grim doctrines of Thomas Malthus, former Chair of Political Economy at Haileybury, still held great sway over the white rajas. Although it was bad manners to openly air such opinions in front of the natives in Calcutta, Malthusian principles, updated by Social Darwinism, were regularly invoked to legitimize Indian fami...