![]()

Part I

Perspectives

on the Problem

![]()

Chapter 1

Consumer Protectionin an Era of Globalization

Cary Coglianese, Adam M. Finkel, and David Zaring

Society has long tolerated some risk in the products consumers buy, especially when the risks are understood to be inherent in the products' use. By their very nature, for example, cigarettes and fatladen desserts pose risks to consumers, and, although some car models may be more crashworthy than others, driving any automobile introduces a degree of risk. But when two identical products sit side by side on a shelf, and one of them might be deadly and the other benign, we have a recipe for serious public health problems as well as major economic consequences from diminishing consumer trust.

The problem of unsafe food, pharmaceuticals, and consumer products coexisting with goods the public assumes to be safe has recently become more acute as a consequence of the boom in global trade. For example, in the span of just two recent years, consumers in a number of countries have endured a series of health crises from products imported from China:

• In 2006, Panama imported from China syrup for cough medicine that contained diethylene glycol—a chemical compound used in antifreeze—instead of glycerin. More than 250,000 bottles of cold medicine were manufactured from the toxic syrup, which fatally poisoned more than 100 people (Bogdanich and Koster 2008). The same poisonous ingredient also made its way into more than 6,000 imported tubes of toothpaste sold in Panama in 2007 (Bogdanich and McLean 2007).

• Multinational toy manufacturers recalled tens of millions of toys in 2007 in response to the discovery of lead paint or unsafe magnetic parts on many popular toys—from Barbie to Thomas the Tank Engine—that were produced in China and sold worldwide (Story 2007).

• A toy product manufactured in China and marketed in the United States as “Aqua Dots” and in Australia as “Bindeez” was found in 2007 to contain beads manufactured with a glue that, when ingested, converted to an analog of the so-called date rape drug, putting at least several children into comas (Bradsher 2007).

• In 2008, milk and milk products from China, including infant formula, were found to contain melamine, a chemical used as a fire retardant that had been illegally added as a thickening agent to increase and mask the protein content of diluted milk. Melamine contamination led to hundreds of thousands of illnesses and numerous deaths in China, as well as to massive product recalls throughout Asia, the Americas, and Europe (Oster et al. 2008). A similar scare in 2007 involved imported pet food contaminated with melamine (Nestle 2008).

• Nearly 150 deaths have occurred globally from the contamination of Chinese-manufactured heparin, a blood thinner used for patients undergoing certain types of kidney dialysis and cardiovascular surgeries (Powell 2008). The heparin manufactured in China was found by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to contain a lower-cost substance—oversulfated chondroitin sulfate—that mimics the anticoagulant effects of pure heparin but may have lethal side effects (Powell 2008).

• An estimated 100,000 homes throughout the United States may contain Chinese-manufactured drywall linked to indoor air pollution— specifically “rotten egg” odors—and to the corrosion of copper piping and air-conditioner coils (CPSC 2009; Lee and Semuels 2009; Schmit 2009). Residents and public health officials are concerned about eye, skin, and respiratory irritation, as well as other health and safety risks, including the possibility of fire or shock from corroded piping and wiring.

China is not the only source of alarm about unsafe products. Government officials around the world have raised safety concerns about products imported from other countries. In 2008, for example, the U.S. FDA barred for safety reasons the importation of more than thirty generic drugs produced by Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd., an Indian pharmaceutical manufacturer (Dooren and Favole 2009).

The need to protect consumers from unsafe food, drugs, and other products is a persistent one—and is certainly not limited to imported products. As with the Chinese deaths resulting from the recent melamine contamination of milk products, the citizens of the countries that export unsafe products can be just as much affected as those in the importing country (Powell 2008). Moreover, national regulatory apparatuses for monitoring domestic producers have been in place around the world for most of the last century to address the same kind of risks that arise from unsafe imports (Vogel 2007). Even in developed countries with longstanding regulatory regimes, domestic products can be as dangerous as any import (Moss and Martin 2009). The same market pressures and consumer demands for cheap goods that may lead some producers to cut corners on safety apply whether products are made at home or abroad: the expansive recall of peanut-based products throughout the United States in early 2009, for example, targeted a Georgia-based processing facility of the Peanut Corporation of America (Zhang 2009). When in 2007 the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) sought to recall defective tires manufactured in China (sold by the aptly named Foreign Tire Sales), the underlying concern was not much different from when NHTSA took action in 2000 against the U.S.-based Firestone company for defective tires produced at a plant in Decatur, Illinois (Aeppel 2007).

Nevertheless, the challenge of protecting consumers from unsafe imports deserves special and intensive analysis at this time of expanding globalization. Not only are safety crises from imported products not going to disappear, but they are likely to increase with international trade. When the world recovers from its recent economic downturn, the flow of goods moving across borders will continue to expand. Already the U.S. economy depends on more than $2 trillion worth of imported goods per year, with more than half coming from Canada, China, Mexico, Japan, and Germany (HHS 2007a). The sheer volume of international trade creates a vast and complex network of the sources of safety problems. More than 825,000 different exporting companies bring products into the United States through more than 300 airports, seaports, and border crossings (HHS 2007a), straining the capacity of national regulatory authorities to inspect products at the borders and monitor facilities at the site of manufacture.

The benefits of international trade are clear: the lowering of trade barriers creates new market opportunities and enhances welfare by lowering costs to consumers. But global trade also contributes to added vulnerabilities. The Indian pharmaceutical company cited by U.S. regulators in 2008 for safety problems was reportedly the sole source of a key children's antibiotic supplied to the New Zealand health system (Das 2008). Even a country such as the United States, which has long placed restrictions on the importation of drugs produced from outside its borders (ostensibly for safety reasons), currently relies on imports for more than 80 percent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients used by its drug manufacturers (GAO 1998). In addition to the vulnerabilities citizens face from goods manufactured in parts of the world not subject to their common “social contract,” the combination of global trade with modern technology's constant innovation in manufacturing techniques, product designs, and formulas makes the challenge all the greater for the regulator of imported products. As Professor Li Shaomin has observed, “When millions of people experiment with new ways to make money without moral self-constraint, the chance of new products that can evade existing testing methods is pretty high” (Xin and Stone 2008: 1311).

The challenge of import safety calls for new policy ideas and analysis. The former U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, Michael Leavitt, noted that “just as the volume of trade has changed, so must the strategies to regulate safety. Simply scaling up our current inspection strategy will not work” (Leavitt 2008: 4).

This book is premised on the view that global trade poses both quantitatively and qualitatively distinct problems for consuming publics around the globe and for those governments charged with protecting them. Although consumers can be harmed just as much by domestic products as by imports, the import safety problem raises a variety of jurisdictional, legal, cultural, political, and practical issues that are not present with domestic product regulation. The research in this book casts a needed light on the distinct nature of the import safety problem, analyzes a variety of innovative solutions to it, and addresses the implications these solutions hold for important social values, ranging from accountability to efficiency.

This book also treats the problem as a general one confronting the food industry, the pharmaceutical industry, and all other industries that manufacture consumer products of all kinds, from tires to toys. In much of the world, separate regulatory laws and institutions have been created to deal with safety problems in different industries. Policy research has often tracked these divisions, with distinct communities of experts focused on food safety, drug regulation, and consumer safety. In editing this volume, we have certainly been mindful of these divisions of expertise, as well as of the varied industrial processes, economic conditions, and sources of safety problems that exist across these domains. The contamination of food products from the E. coli bacterium is obviously quite a different policy problem than the risks of tread separation in automobile tires. The risks to different subpopulations of the public may also vary depending on the type of product, ranging from children with toys to the elderly and immunocompromised populations with pharmaceuticals. Yet, as much as we recognize these differences, we also resist dividing the import safety issue into separate problems of regulating the safety of imported food, drugs, and consumer products. Decision makers and analysts in each of these domains confront the same fundamental policy choices and, broadly speaking, the same kinds of challenges. Those with a particular interest in one domain can learn from the experiences in other domains and from efforts, such as this book represents, to generalize across different domains.

The Import Safety Problem

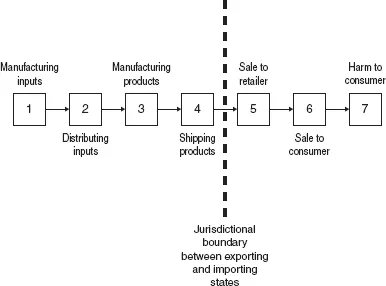

We begin with a straightforward understanding of the problem of import safety. The ultimate concern is to avoid the adverse health effects that arise from lapses in safe practices. Such lapses could arise from a variety of possible sources, some intentional, others simply accidental. The schematic shown in Figure 1 provides a highly simplified model of the various links in the causal chain that leads to consumer harm from imported products. At each step along the way there is the possibility for tampering and contamination—from the initial creation of ingredients or other product inputs to the manufacturing, shipment, and sale of the product. As the schematic shows, protecting import safety requires oversight of a complex welter of inputs on both sides of the border.

The actual causal chain for unsafe imports is much more complex. Ingredient and input production is often undertaken by entities separate from those involved in manufacturing itself (Neef 2004). Consumer products can contain many components, drugs often include numerous different ingredients, and food products comprise the outputs of numerous farmers and ranchers. Supply chains, especially in countries as large as China, can be vast and complicated. The schematic in Figure 1 fails to represent this complexity. Furthermore, in reality, the vertical jurisdictional line in the figure can be placed at more than one step in the more complex chain that leads to real consumer harm. Manufacturing can even take place in the importing state, with just product components imported. Large manufacturers and large retail operations, such as “big box” stores, rely on many different sources around the world. As a result, the number of individuals who could tamper with or contaminate a product can be quite substantial. For any given imported product, each step in the causal chain can involve numerous different actors, each with their own incentives, constraints, knowledge, capacity, and motivations.

Figure 1. Causal steps to import safety problems.

At some point from the initial ingredient production to the sale and use by consumers, an imported product moves from one jurisdiction to another. That movement over a jurisdictional border—from the exporting state to the importing one—qualitatively distinguishes the problem of import safety from the “ordinary” problems all governments face in policing the safety of food, drug, and consumer products within their borders. What the dotted vertical line in Figure 1 represents is the qualitatively different problem of import safety, one that brings with it an additional set of regulatory challenges. These challenges can be legal, cultural, and even practical. Just identifying who manufactured an ingredient can sometimes be difficult when records are kept in another country and in another language. For example, in 2001 a pair of FDA inspectors were reportedly unable to conduct an inspection of a Chinese facility producing acetaminophen imported into the United States because they simply could not find where the facility was located (Harris 2008). Even when harm can be practically traced back to sources in other countries, regulatory and legal liability may not extend overseas, effectively giving importers a “free ride” on the harm that their products impose on consumers.

In addition to the challenges of monitoring and enforcing safety abroad, international trade complicates consumer protection still further when nations exhibit different cultural postures toward risk and place different domestic priorities on the use of government regulatory resources (Douglas and Wildavsky 1982; GAO 2008b). Even if some cross-cultural risk threshold exists above which no consumer should be expected to suffer, it is still undoubtedly the case that the consuming publics in wealthy importing nations will often have different expectations for safety than consumers in developing countries. Even wealthy publics in different parts of the world—Europe versus the United States, for example—can differ in their perceptions of what product safety means, both across countries and within them (Ansell and Vogel 2006; Hanrahan 2001; Meijer and Stewart 2004). These differences factor not only into differences in government-imposed safety standards, but also into political and institutional choices about what types of domestic regulatory organizations to create and how to fund them, choices that are affected by competi...