![]()

1

Making the Suit Zoot

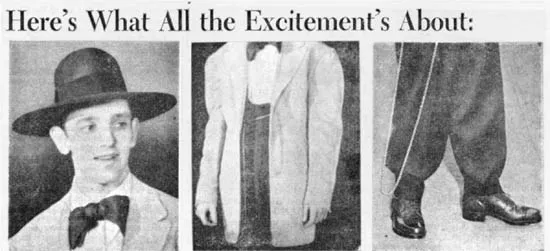

When civil unrest and violence erupted in Los Angeles in June 1943, the zoot suit became a preoccupation of adult Americans across the country: What was the zoot suit and where had it come from? “Here’s what all the excitement’s about,” explained the newspaper PM, which ran a photographic triptych of the garment and its accoutrements. Reporters interviewed young men in Harlem, photographers snapped pictures of the drape shape, and columnists gave their angle on the phenomenon. “Last week practically everybody with any pretensions to journalism was ferreting out the origins of the zoot suit,” observed the New Yorker.1

As it turned out, there were many conflicting stories about the genesis of the style. Tailors from New York to Memphis claimed to have invented it, while an obscure busboy in Georgia insisted on bragging rights. However tall the tale or self-aggrandizing the teller, these origin stories open a window into the making of an extreme fashion, before the zoot suit became the object of public commentary. They reveal the unusual commercial and creative exchange among manufacturers, retailers, and consumers that transformed normal menswear into something spectacular. The men’s garment industry and clothing styles had changed in the face of the Great Depression, and clothiers found a variety of ways to respond to it, with some embracing novel fashions and fads. Among the young men who ordered and wore the zoot suit, a new aesthetic sensibility can also be discerned despite the disapproval of parents and tailors.

Figure 1. One newspaper’s version of the zoot suit, the white model rendering it harmless. PM, June 13, 1943.

Most fashions run their course, but the zoot suit’s path, perhaps uniquely in clothing history, was rerouted by the onset of World War II. Even as manufacturers and retailers promoted the style and young people embraced it, the government moved to clamp down on the wasteful use of textiles. If federal officials had their way, the zoot suit would have been a home-front casualty. Indeed, their efforts to prohibit the zoot suit and render it unpatriotic contributed greatly to the perception of the style, then and now, as a symbol of opposition to mainstream American values. The state’s assertion of its regulatory role is a crucial aspect of the history of the zoot suit, affecting the manufacture, retailing, and marketing of this type of menswear. Although the intentions of such regulations were clear, their impact was far more ambiguous, fueling fascination with the very style the government sought to suppress.

The zoot suit was, in the first place, a suit, a garment made of cloth cut and sewn to cover and ornament the body. What made it “zoot” was the way it pulled out the lines and shape of the traditional suit to widen a man’s shoulders, lengthen his torso, and loosen his limbs. The style itself varied from man to man and place to place, but however it was worn, it broadcast a self-conscious sense of difference from the conventional mode of respectable male appearance. Most Americans viewed the zoot suit as something new and peculiar, but those with a long memory recalled earlier periods when men put on similar outfits. Walter White, secretary of the NAACP, offered the perspective of a middle-aged man who had seen fashions come and go. “In the late 90’s and early 00’s long box back coats, full or peg-legged trousers, and flat felt or straw hats called boaters or pork pies, were worn on Fifth Avenue and Park Avenue as well as other places,” he observed. “The modern zoot suits exaggerate but little the modes which will be remembered by many of us.” The Chicago Tribune agreed, reminding readers what the well-dressed man of 1901 was wearing and recalling the fad for “Oxford Bags,” voluminous pants worn by British university students, in the 1920s.2

These observers had a point: A practice of extreme styling had long been common in menswear. In the history of Western dress, the suit has enjoyed remarkable longevity. A banker in antebellum Boston would recognize his counterpart in today’s global economy: matching jacket and trousers, simple lines, subdued colors, woven fabrics tailored to the body, lack of ornamentation except for a tie or cravat. Still, over its long history, the men’s suit has varied in numerous if subtle ways, with styles deemed extreme or outré playing against the governing type. This dynamic may be seen in the emergence of the zoot suit amid broad changes in men’s appearance.

The arrival of the men’s suit is often termed the “great masculine renunciation,” a fundamental shift in the way men looked and thought about their attire. Before the 1600s, elite men had worn rich textures, colors, and ornamentation, the pomp of their dress conveying their rank. According to clothing historians, the suit redefined the relationship between appearance and authority in an era of political, social, and cultural transformation that challenged crown and church. The Protestant reformation, the American and French revolutions, and the growth of trade all reshaped attitudes toward the self, body, and clothing. Belief in equality and individualism made the showy display of wealth and rank increasingly suspect. Powdered hair, lace and ruffles, and ornate fabrics were out. As they gained economic power, a bourgeois merchant and manufacturing class set new norms of proper appearance. By the early 1800s, men’s authority rested increasingly on the projection of character and ability; thus inconspicuousness became the hallmark of the well-dressed man. Ornamentation and display were left largely to women, their fashions marking not a powerful rank but rather their status as the weaker sex. Men—now self-reliant, self-motivated individuals—no longer dressed their bodies to be the object of attention.3

Nevertheless, there were always some young men who tried to make spectacles of themselves. Long before the arrival of the zoot suit, they embraced vibrant colors and arresting silhouettes as a mark of distinction and fashion. In nineteenth-century cities, wealthy young men-about-town and sporting men adopted modish looks for evening entertainment, the racetrack, and promenading. The dandy’s attention to appearance was legendary. “A Man whose trade, office, and existence consist in the wearing of Clothes,” Thomas Carlyle pithily defined him: “Others dress to live, he lives to dress.”4 Stylishness was also a point of pride among working men of few means. Irish American mechanics and firefighting “laddies” wore cheap clothing and castoffs that nevertheless mixed colors, fabrics, and details in ways that demanded notice. Among them, the Bowery Boy stood out: Parading lower Manhattan in a top hat, fitted frock coat, bright vest, and plaid trousers, he became a social type popularized on the stage in the years before the Civil War.

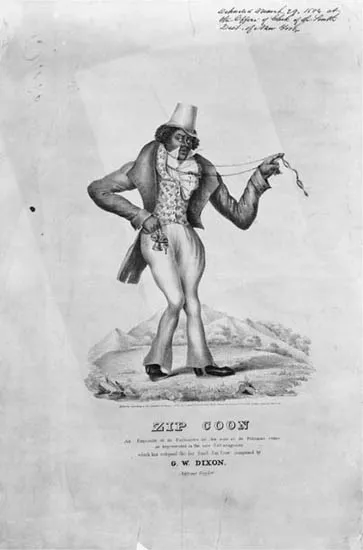

Similar clothes might be worn by African American men of the 1800s, for whom “styling” was an especially rich tradition bound up with the cultural encounters of Africans and Europeans, the experience of slavery, and the role of religion, festivals, and celebration in everyday life. Dressing up breached class and racial codes of subservience. Those with few resources might use style to convey visually a sense of masculine identity, stake out a public space, and demand that others acknowledge their presence. Urban black men’s flamboyant dress was so much in evidence that it fueled the look of minstrelsy, even as minstrelsy turned the desire to look fine into a racist stereotype. Thus the popular song “Zip Coon,” introduced by the white minstrel George Washington Dixon in 1829, mocked the “natty scholar” for his pretensions; the image used on the sheet music prefigured the zoot suit, with its broad-shouldered frock coat, pleated trousers, watch fob, and glasses attached to a long chain.5

Figure 2. Mose the Bowery Boy, a fashion-conscious “fire laddie” of New York’s East Side.

Gene Schermerhorn, Letters to Phil, Memories of a New York Boyhood, 1848–1856 (New York: New York Bound, 1982).

For some men, then, fashion had long punctuated ordinary life with extraordinary looks. Among African American freemen, Irish-born residents, and working-class youths, they embraced an aesthetic that played with high and low styles, and insisted above all on public visibility. Such styles served to make distinctions and even recalibrate social position, but they could also be used to craft larger points, a visual commentary with a political edge. Still, extreme style only worked in its relation to governing codes of appearance of a given time. Top hats, walking sticks, and vests were ripe for the picking by poor young men who wished to stand out, but these and other markers of Victorian formality and wealth would fade in a changing social and cultural climate.

The early twentieth century witnessed a gradual loosening of the form and style of menswear. The “sack” jacket, with straight lines and natural shoulders, appeared by 1900, initially long and loose, then somewhat shorter by World War I. A greater change occurred in the 1930s, when the “London cut” or “English drape” grew popular. Wanting to produce a body-conscious, masculine effect, London tailor Frederick Scholte designed a suit that looked like “a V resting on an attenuated column.”6 Jackets featured wide shoulders and chest, roomy armholes, and narrowed waist, and were worn with high-waisted, tapered pants. Perfect proportions were critical to Scholte, who made his suits for the carriage trade and refused requests for exaggerated shapes and details, which he associated with entertainers.

Nevertheless, the style created by a London bespoke tailor quickly came to epitomize the look of American men. In the midst of the Great Depression, when men’s role as breadwinner and household head was on trial, the drape cut emphasized male athleticism and virility, the heman and the man of action. The flow of the fabric eased men’s stance, relaxed the way they inhabited their clothes, and swung with the body. Hollywood embraced the drape cut in the mid-1930s, producing different versions to convey distinct character types. While such leading men as Cary Grant and Clark Gable wore impeccable draped suits that were integral to their screen personas, James Cagney and other movie gangsters wore more exaggerated broad-shouldered “breakaway” jackets that cut in at the waist. Even period films had an influence on contemporary fashion, especially the eye-catching frock coats and wide-brimmed hats worn by Gable in Gone with the Wind (1939) and Errol Flynn in Virginia City (1940).7 By 1940 the drape style had become widely known as the “American cut,” and it would continue to define a national masculine ideal through the 1950s.

Figure 3. The minstrel figure Zip Coon caricatures the high style of urban African Americans.

Endicott & Swett sheet music, 1834, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-126131.

During these years, the menswear trade as a whole became a more style-conscious industry. As the Great Depression deepened, Americans cut back on clothing expenditures. With money tight, families carefully weighed the decision to buy a new business suit for the male breadwinner, as it meant that wives would have to scrimp on new clothes and refurbish old ones for themselves and their children. Looking for ways to save money yet look presentable, men made a virtue of necessity, going without hats and vests, and mixing jackets with mismatched trousers. In response, manufacturers tried everything from drastic price-cutting to novelty styles in order to persuade consumers to buy. Some began to adopt a new sales strategy focused on style promotion and marketing. Arguing that price warfare was destroying business, journalist and editor Arnold Gingrich urged manufacturers and retailers to foster greater fashion awareness and consumerism among American men, which would lead them to pay a premium for stylish clothing. Toward this end, he created the magazine Apparel Arts in 1931 for the men’s clothing trade and founded Esquire as a “magazine for men” two years later. Although lagging behind women’s fashions, menswear manufacturers and retailers sought “tie-ins” with style-conscious celebrities, from Hollywood stars to Edward, Duke of Windsor. “I was in fact ‘produced’ as a leader of fashion, with the clothiers as my showmen and the world as my audience,” observed the duke, who assiduously posed for photographs and encouraged the British export trade with his signature style of soft dressing and touches of eccentricity.8

The 1930s also saw the takeoff of men’s sportswear and casual clothing. Initially confined to athletic fields and the outdoors, sportswear crossed over into everyday street life. To many it seemed a style for hard times, as men limited their expenditures for clothing, especially suits. California had emerged as the center of American sportswear manufacture for both women and men, and the Golden State’s relaxed lifestyle and sunlit ambiance led designers to create colorful, looser fitting, and casual clothes. This trend grew during World War II. When the government ordered the conservation of wool, many men swapped their business suits for assorted sports jackets and pants. Office workers who switched to higher-paying industrial jobs did not want to wear factory uniforms or overalls—a sign of blue-collar status—and put on a T-shirt and slacks instead. “A year ago this outfit might have been worn for a golf game,” the Men’s Apparel Reporter remarked. “Today it is a uniform for the war worker.” The trade journal warned manufacturers to rid sportswear of its associations with idle wealth and effeminacy. “It just isn’t funny any more to promote or display sports clothes that have a dash of lavender,” it admonished. “This nation has got to get tough.”9

The men’s garment industry also turned to the youthful fads of the day, styles that adults would consider bizarre or outré. They began to cater to tastes for novelty through a manufacturing classification called “extremes,” jackets and trousers with unusual colors, cuts, and styling. Style spotters for the industry went to the Yale Bowl, the Princeton campus, and the Belmont racetrack to search out new looks. By 1940 they were finding affluent young men sporting long, loose jackets and bold colors and plaids, styles they sold as “collegiate.” Popular trends in music, dance, and film also insp...