![]()

PART I

ASHORE AND AFLOAT

![]()

1

The Sweets of Liberty

Horace Lane first went to sea when he was ten years old. By the time he was sixteen he had been pressed into the British Navy, escaped, traveled to the West Indies several times, and witnessed savage racial warfare on the island of Hispaniola. Although he experienced many of the perils of a sailor in the Age of Revolution, he avoided the wild debauchery of the stereotypical sailor ashore. In 1804, after a particularly dangerous voyage smuggling arms and ammunition to blacks in Haiti, his rough-and-tumble shipmates from the Sampson cruised the bars, taverns, and grog shops of the New York waterfront. One night a shipmate took him to the scene of the revelry. Lane remembered that “after turning a few corners, I found myself within the sound of cheerful music.” As they approached the door, Lane hesitated. His companion shamed him into entering by declaring “What…You going to be a sailor, and afraid to go into a dance-house! Oh, you cowardly puke! Come along! What are you standing there for, grinning like a sick monkey on a lee backstay!” Lane could not handle the rebuke. Gathering himself, he mustered enough spunk to enter. No sooner had he crossed the threshold than he was met with “a thick fog of putrified gas, that had been thoroughly through the process of respiration, and seemed glad to make its escape.” The room was packed with the humanity of both sexes and several races. In one corner loomed a huge black man “sweating and sawing away on a violin; his head, feet, and whole body, were in all sorts of motions at the same time.” Next to him was a “tall swarthy female, who was rattling and flourishing a tamboarine with uncommon skill and dexterity.” A half dozen other blacks occupied the middle of the floor, “jumping about, twisting and screwing their joints and ankles as if to scour the floor with their feet.” Everywhere people shouted, “Hurrah for the Sampson!” Among the crowd some were swearing, “some fighting, some singing; some of the soft-hearted females were crying, and others reeling and staggering about the room, with their shoulders naked, and their hair flying in all directions.” Lane was horrified and beat a hasty retreat, proclaiming “Ah!…Is this the recreation of sailors? Let me rather tie a stone to my neck, and jump from the end of the wharf, than associate with such company as this!”1

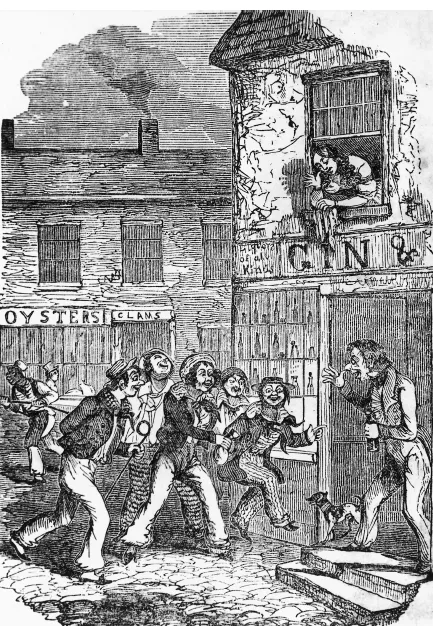

1. While on liberty in a port, sailors spent money freely on liquor. Notice the woman in the window, probably a prostitute, and the black man in the background walking in front of the oyster and clam shop. “Sailors Ashore.” From Hawser Martingdale, Tales of the Ocean… (Boston, 1840). New Bedford Whaling Museum.

A few more years, and many more adventures at sea, led to a change of heart. Lane recounts his conversion to hard living. He had agreed to deliver a letter to a young woman who worked at “French Johnny's,” a notorious dance hall on George Street in New York. As he worked his way through the crowd outside, he approached the door blocked by a chain and a guard. After paying the cover charge, Lane stepped into “a spacious room, illuminated with glittering chandeliers hanging in the centre, and lamps all around.” He was awestruck. “Never was there a greater invention contrived to captivate the mind of a young novice.” Three musicians sat on their high seats and there were “about fourteen…damsels, tipped off in fine style, whose sycophantic glances and winning smiles were calculated only to attract attention from such as had little wit, and draw money from their pockets.” Lane admitted that he “was just the man” and declared, “This was felicity indeed.” Lane bought some hot punch, finding that after a while it tasted good. He summarized the rest of the experience in verse:

So I spent my money while it lasted,

Among this idle, gaudy train;

When fair Elysian hopes were blasted,

I shipp'd to sail the swelling main.2

Horace Lane offers us a wonderful view of liberty ashore. He allows us to follow him into the sailor's haunts by evoking a powerful sense of the sounds, sights, and even smells that enticed many young men into a particular mode of life. At first repulsed by the depths to which he sees his comrades of the Sampson have fallen, marked by the racial mixture of the waterfront dive, he is seduced by the light of chandeliers and damsels “tipped off in fine style” at French Johnny's. Lane's saga goes downhill from there, leading to a round of drunken debauchery and criminality, interspersed with adventures spread across the seven seas. Ultimately his is a tale of redemption that condemned the depravity that seemed to accompany liberty ashore.

Others viewed the sailor's liberty differently. Richard Henry Dana, Jr., and Herman Melville knew a great deal about the sea, both having served in the forecastle—where common seamen slept—in the nineteenth century. Dana wrote that “a sailor's liberty is but for a day; yet while it lasts it is perfect.” The tar thus experienced an exuberance of liberty that was denied most others. Released from shipboard discipline, Dana asserted that he was “under no one's eye, and can do whatever, and go wherever, he pleases.” Of his own initial “liberty” Dana exclaimed, “this day, for the first time, I may truly say, in my whole life, I felt the meaning of a term which I had often heard—the sweets of liberty.”3 Melville, in his own sardonic style, reiterated this point and captured the spirit of a world turned upside down when he declared that “all their lives lords may live in listless state; but give the commoners a holiday, and they out-lord the Commodore himself.”4

Implicit in the views of both Dana and Melville is a political meaning of the word “liberty” that appears to belie the experience of Horace Lane. For Dana, the sailor's liberty gave him a sense of personal freedom, a release from restraints that bound his life at sea. Melville, whose work speaks more directly to the American democratic soul, has an understanding based on the collective experience of liberty. The sailor's holiday liberates not only the individual, but also the group, and enables the commoners to rule triumphant even if only momentarily. Lane, in contrast, bemoans the liberty ashore, viewing it as both a trap and a release that in many ways defined his very essence as a sailor. Lane sees this liberty as one component of the life of Jack Tar.

To understand the world of the waterfront, we must take a careful look at the sailor's liberty ashore, exploring the widely held image of the jolly tar. Sailors were not a proletariat in the making, nor were they a peculiar brand of patriot. They were real people who often struggled merely to survive. Sailors were a numerous and diverse body of people who shared a common identity. The great variety of men who comprised the waterfront and shipboard workforce, and the fact that many sailors did not fit the stereotype, will be the focus of this chapter.

At sea the sailor worked hard. His life was one of regulation from above and dangers all around. Ashore there was a sudden release. He could drink, curse, carouse, fight, spend money, and generally misbehave. For the sailor ashore there was no future, only the here and now. Although this image was not flattering, sailors were also often described as generous and tenderhearted. More important, the stereotypical sailor represented a culture and value system that challenged the dominant ideals of both the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Not only did the sailor ashore reject the traditional hierarchy of pre-revolutionary society, but his behavior represented the antithesis of the rising bourgeois values that became the hallmark of the Age of Revolution. Whether consciously or not, sailors played a role that had profound implications for the waterfront community and workers throughout society.

Drinking was a central part of the sailor's liberty ashore. Minister Andrew Brown's sermon in the 1790s on the dangers of the seafaring life focused as much on intemperance on land as on the perils of the deep. He cautioned that “the spirit of prodigality and wastefulness,” terms he used synonymously with drinking to excess, “has long been regarded as one of the distinguishing characteristics of the seafaring life.” He believed also that drinking “has been sanctioned by custom, and is now almost converted into a professional habit.”5 Forty years later, the members of the New-Bedford Port Society recognized “the exuberant joy” a sailor experienced once he came ashore and his eagerness for drinking whetted by the relative abstinence at sea. The New-Bedford Port Society also acknowledged the social pressures felt by a tar, admitting that he drinks “in token of cordiality and good will,” and that “he treats his acquaintance in sign of generosity, or to escape the imputation of meanness.”6 After a long voyage, as other sailors busied themselves with calculations of “airy castles,” one man honestly admitted that he would get drunk as soon as he got ashore, declaring, “it is the only pleasure he has in the world, and when he is pretty well in for it, he is as happy as any man in it.”7 The centrality of drinking to both the image and the reality of the sailor can be seen in popular depictions. Infused with a spirit of patriotism, and perhaps recognizing that sailors enjoyed the stage, creators of theatrical performances in the 1790s often included songs and portrayals of the American tar. In Songs of the Purse sailor Will Steady sings:

When seated with Sall, all my mesmates around,

Fal de ral de ral de ri do!

The glasses shall gingle, the joke shall go round;

With a bumper! then here's to ye boy,

Come lass a buss, my cargoe's joy.

Here Tom be merry, drink about,

If the sea was grog we'd see it out.8

Several songs and sea chanteys celebrated the sailor's drinking ashore.9 In “Whiskey,” the men proclaimed:

Oh, whiskey is the life of man.

Oh, whiskey, Johnny!

2. Jack Tar took great pride in his dress and his ability to dance and show off. This interior of a tavern has men drinking, a dancing sailor, a black man playing the fiddle, and several women with low-cut dresses in a scene similar to the ones described by Horace Lane. “Sailor's Sword Dance.” From Hawser Martingdale, Tales of the Ocean… (Boston, 1840). New Bedford Whaling Museum.

It always was since time began,

Oh, whiskey for my Johnny!

The nineteenth-century chantey, sung while dragging ropes to hoist upper

topsails, goes on to praise whiskey even though

Oh whiskey made me wear old clothes

And whiskey gave me a broken nose

Oh, whiskey caused me much abuse,

And whiskey put me in the calaboose.

The final stanza calls for a round of grog for every man, “And a bottle full for the chanteyman.”10 The self-mocking good cheer that underpins this chantey can also be seen in “The Drunken Sailor.” The tars ask, “what shall we do with a drunken sailor?” only to answer, “Chuck him in the longboat till he gets sober.”11 As Samuel Leech, veteran of thirty years at sea put it, seamen viewed drinking as “the acme of sensual bliss.”12

Along with excessive drinking, the sailor set himself apart by his language. The waterfront had its own peculiar argot. James Fenimore Cooper's sea novels depict the common seaman's idiom, but Cooper never could offer his reader the sailor's real language—curse, followed by curse, followed by curse.13 Samuel Leech proclaimed that sailors “fancy swearing and drinking” were “necessary accomplishments of a genuine man-of-wars-man.”14 In a sermon offered especially for fishermen in Beverly, Massachusetts, before the spring run of 1804, Reverend Joseph Emerson urged them to trust in God, observe the Sabbath, and avoid swearing. As he stood before the weatherworn faces of the fishermen, he acknowledged that he understood how hard it was for sailors not to use strong oaths.15 Common seamen prided themselves in swearing. Simeon Crowell admitted that as a young man about twenty in 1796 he took up bad language while in a fishing schooner off the Grand Banks. By the following year, his cursing had become so elaborate that he thought he might have shocked even some of the old salts with his “wicked conversation.” He also had “learned many carnal songs with which” he “diverted the crew at times.” Unfortunately, he did not copy any of these songs into his commonplace book. He did, however, offer a poem, “The Sailor's Folly,” which he wrote in Charleston, South Carolina, on February 13, 1801:

When first the sailor comes on Board

He dams all hands at every word

He thinks to make himself a man

At Every word he gives a dam

But O how shameful must it be

To Sin at Such a great Degree

When he is out of Harbour gone

He swears by god from night to morn

But when the Heavy gale doth Blow

The Ship is tosled to and froe

He crys for Mercy Mercy Lord

Help me now O help me God

But when the storm is gone and past

He swears again in heavy Blast

And still goes on from Sin to Sin

Now owns the god that Rescued him16

Drinking and cursing ashore were a part of the general carousing that marked the sailor's life on the waterfront. One sailor looked back at his life and proudly pointed to his accomplishments at sea and ashore. Bill Mann had tremendous black whiskers and the “damn-my eyes” look of an old salt. Mann declared that he “had killed more whales, broken more girls' hearts, whipped more men, been drunk oftener, and pushed his way through more perils, frolics, pleasures, pains, and general vicissitudes of fortune than any man in the known world.”17 Such a sailor was supposedly hell-bent to live it up while ashore. According to J. Ross Browne, “a sailor let loose from a ship is no better than a wild man. He is free; he feels what it is to be free. For a little while, at least, he is no dog to be cursed and ordered about by a ruffianly master. It is like an escape from bondage.”18 George Jones described the experience of “liberty men” on an American warship in the Mediterranean in 1825: “They go; fall into all manner of dissipation; get drunk; are plundered; sell some of their clothes, for more drink; quarrel with the soldiers; come back with blackened eyes; cut all kinds of antics; become rude and noisy; are thrown into the brig; have the horrors, and then go about their work.”19

Carousing frequently led to fighting. Often members of a crew, like Horace Lane's shipmates on the Sampson, bonded together, ready to take on all comers. Similarly in 1814, more than one hundred of Stephen Decatur's men from the frigate President were arrested after a fracas at a New York tavern. In this instance there were no serious injuries.20 Other brawlers were not so lucky. In 1812 a group of drunken sailors attempted to gain entry into a New York dance hall but were excluded by the Portuguese owner, who claimed that he was having a private party. Insulted and outnumbered, the sailors left. On their way back to their waterfront boardinghouse, they met some shipmates. With that reinforcement they returned and tried to force their way in. The Portuguese came charging out, swinging their knives and killing one of the sailors. These conflicts occurred countless times in almost every port.21

One of the sailor's problems, leading to the drinking, carousing, and even some fighting, was that he often had money jingling in his pocket. After being paid off from a voyage a seamen might have a month's or as much as a year's wages at his fingertips. Even before the voyage, once he signed the articles of agreement, he was usually paid a month's wages. Most tars flouted mainstream values and asserted their liberty by spending that money—that chink—just as quickly as they could. Thomas Gerry, son of politician Elbridge Gerry, wrote home from aboard the frigate Constellation t...