![]()

CHAPTER 1

Development Clusters

Little else is required to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice, all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things.

Adam Smith, 1755

Almost all economic analyses presume the existence of an effective state. Specifically, economists invoke the existence of an authority that can tax, enforce contracts, and organize public spending for a wide range of activities. We then study concepts such as market failure and the state's response to it, the provision of public goods, and optimal taxation for the funding of state activities. But many of the major developments in world history have been about creating this starting point. Arguably, the situation presumed by economists is relevant only to the past 100 years of history for a fairly small group of rich countries.

The effective state is not only of historical interest. A tour of the developing world today rapidly confirms that the building of a state capable of taxing, spending effectively, and enforcing contracts remains a huge challenge. Weak and failing states are a fact of life and a source of human misery and global disorder.

These observations are especially poignant because income per head in the world's richest countries is about 200 times higher than in the poorest. This enormous income gap is certainly one of the most pressing issues facing humanity. Why some countries are rich and others poor is indeed a classic research question not only in economics, but in other social sciences such as economic history and political science as well. To better grasp the roots of wealth or poverty of nations is interesting in and of itself. But these roots are also of paramount importance for donors seeking to improve the lot of poor communities through various forms of development assistance.

It has long been understood that economic development is about much more than rising incomes. Indeed, state effectiveness is now given center stage in practical policymaking, with a greater focus on how to deal with countries hobbled by weak, fragile, or failed states. A number of national and international actors—such as the World Bank, the European Union, DFID in the United Kingdom, and SIDA in Sweden—have recently launched initiatives targeted toward such problem states.

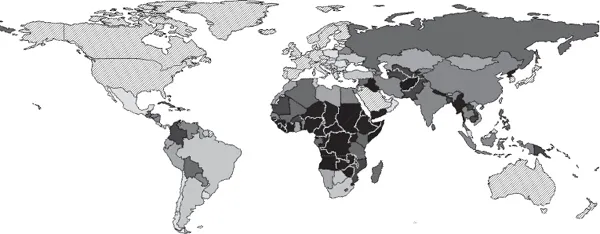

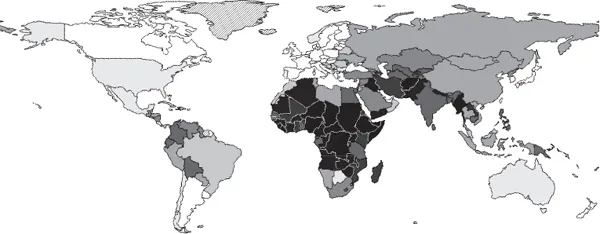

Specific Indexes of State Weakness and Fragility Alternative attempts have been made to map the problem empirically, relying on a variety of measurable indicators.1 Figures 1.1 and 1.2 illustrate two specific indexes of state fragility/weakness, namely the Brookings Institution's Index of State Weakness for all but the richest countries in 2008 and the Polity IV project's State Fragility Index for all countries in 2009. Both of these maps illustrate the underlying classification on a gray scale. Specifically, the countries in the decile with the weakest or most fragile countries are colored in black, whereas deciles higher up in the classification are marked on a sliding gray scale, with white denoting the decile with the strongest states (missing countries are marked by a hatch pattern).2

Although the precise classifications behind the indexes differ, both studies find that some 40-50 states suffer from serious weakness or fragility, with the strongest concentrations in Sub-Saharan Africa and South and Central Asia. Of course, there is no general agreement on exactly what defines a weak or fragile state. The State Fragility Index, e.g., is derived by aggregating indicators in eight dimensions, aimed at capturing the effectiveness and legitimacy of the state in the security, political, economic, and social spheres.3

A closer look at the underlying indicators raises a number of issues. Economic legitimacy is measured by the export share in manufacturing, but exactly how to read this indicator is unclear. Leadership duration is the indicator for political effectiveness, where the direction of the relation is also opaque. Although these may seem like minor quibbles, they touch upon a deeper issue in understanding state fragility—the need to distinguish carefully between symptoms and causes. But this is next to impossible absent a properly developed conceptual framework. These questions notwithstanding, the indexes in Figures 1.1 and 1.2 clearly bring home one point on which we certainly can agree: state fragility (or state weakness) is inherently a multidimensional concept.

Figure 1.1 Brookings Index of State Weakness, 2008.

Figure 1.2 Polity IV State Fragility Index, 2009.

A Challenging Agenda This book offers an approach to studying weak or fragile states, taking a first step toward bringing them into mainstream economic analyses. It is the hallmark of mature science that existing ideas should be expanded into new domains. We proceed in this spirit by using more-or-less standard ideas and methods to study the basics of state building. A key issue is to understand what creates effective states.

Central to our approach is the idea of complementarities. As shown in what follows, almost all dimensions of state development and effectiveness are positively correlated. Moreover, historical accounts demonstrate vividly that state authority, tax systems, court systems, and democracy coevolve in a complex web of interdependent causality. Simplistic stories that try to paste in unidirectional pathways are thus bound to fail.

However, this complexity does not mean that a quantitative approach of theorizing and looking at data is hopeless. On the contrary, we argue throughout the book that building models as stripped-down representations of reality provides useful windows onto complex processes, which allow us to see particular features more clearly. Furthermore, looking at data and trying to codify empirical regularities does more than simply breathe life into the narrative. The data play a central role in developing our thinking about what is important and what can be observed. Indeed, the modeling we put forward is structured around variables and magnitudes that can be both theoretically defined and, in principle, empirically measured. This disciplines the theory and extends the domain of its applicability.

This introductory chapter lays out many of our main ideas in brief but accessible form. It is also an opportunity to review some of the historical evidence and discuss some narrative accounts of development that shape our thinking. But we do not intend our review to be exhaustive. Our primary aim is to demonstrate a strong link between our work, with its clear roots in mainstream economics, and research within other disciplines and less mainstream approaches.

1.1 Salient Correlations

Several characteristics beyond income per capita enter our intuitive perception of the defining qualities of a developed country. One is the institutional capability of the state to carry out various policies that deliver benefits and services to households and firms. We refer to this capability as state capacity. Another development characteristic is that conflicting interests can be resolved peacefully, rather than by alternative forms of violence. We refer to (the inverse of) this feature as political violence.

Policy failures owing to weak state institutions tend to be found in countries riddled with massive poverty and in societies plagued by violent internal conflicts. In most developed countries, by contrast, nearly everything works: we see strong policies supported by strong state institutions, high incomes, and conflicts of interest resolved peacefully. These correlations create development clusters, where the level of state capacity and the propensity for political violence vary systematically with the level of income. Thus, our notion of clusters does not describe a strong correlation for the same outcome variable in a set of neighboring countries (even though Figures 1.1 and 1.2 hint at such geographical clustering). Rather, we use the concept to describe strong correlations among different outcome variables in the same country. To better understand these clusters as manifestations of the general development problem is one of the major objectives of this book.

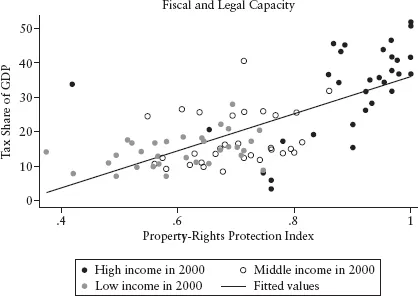

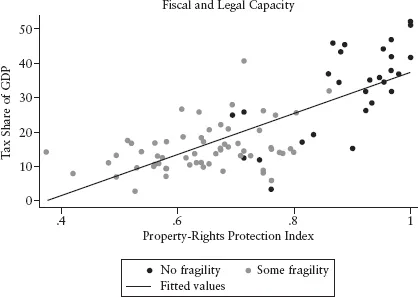

Fiscal and Legal Capacity To illustrate the clustering, we need some concrete empirical measures. For state capacity, we can distinguish two broad types of capabilities that allow the state to take action. One concerns the extractive role of the state. We call this capability fiscal capacity. Does a government have the necessary infrastructure—in terms of administration, monitoring, and enforcement—to raise revenue from broad tax bases such as income and consumption, revenue that can be spent on income support or services to its citizens? The other type of capacity concerns the productive role of the state. Is it capable of raising private-sector productivity via physical services such as road transport or the provision of power? Or does it have the necessary infrastructure—in terms of courts, educated judges, and registers—to raise private incomes by providing regulation and legal services such as the protection of property rights or the enforcement of contracts? We focus on the latter capability, which we refer to as legal capacity.

In later chapters, we consider different measures of both types of state capacity. For now, we illustrate them with two specific measures. The first is total tax revenue as a share of GDP, as measured by the IMF at the end of the 1990s (in 1999). We treat the overall tax take as an indicator of fiscal capacity. The second is an index of government antidiversion policies, as measured by the International Country Risk Guide, also at the end of the 1990s (in 1997), and normalized to lie between 0 and 1. This index is itself an aggregation of different perception indexes, but it has been commonly used in the macro development literature to gauge the protection of property rights.4 We treat it as an indicator of legal capacity.

As we emphasize later, fiscal and legal capacity are concepts that have not been much studied by economists, so precise measurement is certainly an issue. For example, using the total tax take raises obvious questions about the capacity to tax versus the willingness to tax. The measures we use in this book are at best approximations of different aspects of state capacity. As we will see, however, the empirical patterns tend to be quite similar for a number of alternative proxies. Chapters 2 to 4 provide much more detail and discussion about our data and their sources.

Some Basic Facts Figure 1.3 shows that these indicators of fiscal and legal capacity are positively correlated. It plots the tax share on the vertical axis and the property-rights protection index on the horizontal axis. A clear picture emerges. Countries that have better fiscal capacity also tend to have better legal capacity. Both measures are also positively correlated with contemporaneous GDP per capita. When we divide the observations into low-, middle-, and high-income countries, according to their 2000 GDP per capita in the Penn World Tables, almost all of the high-income countries lie to the northeast in the chart, whereas the low-income countries lie to the southwest. Moreover, the positive relationship between fiscal and legal capacity is apparent within each of the three income groups.

The two uppermost observations in the northeast corner of the graph are Denmark and Sweden, both with high income, an overall tax take above 50%, and a level of property-rights protection on a par with other top performers such as Switzerland. The two leftmost observations in the southwest corner are Mali and Niger, both with low income, among the lowest tax takes, and the two worst scores in our sample on the property-rights protection index. A few outliers among the high-income countries stand out by deviating significantly from the regression line. The observation with a tax share above 30% of GDP and one of the lowest indexes of property-rights protection is the Seychelles. The group of three high-income countries charging less than 10% of GDP in taxes is made up of the oil states of Bahrein, Kuwait, and Oman.

Figure 1.3 Legal and fiscal capacity conditional on income.

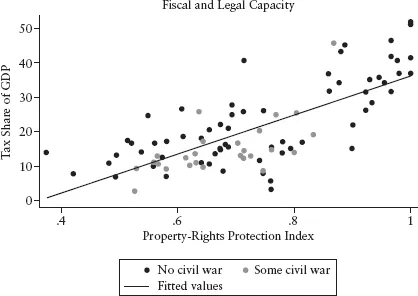

Figure 1.4 illustrates that the two dimensions of state capacity are also systematically correlated with political violence. Specifically, we divide the countries into two groups: those that have experienced at least one year in civil war in the half-century between 1950 and 2000 and those that have not, according to the Armed Conflict Dataset (ACD). Clearly, past civil-war experience is much more common at low levels of state capacity. Two countries in the upper part of the graph stand out a bit. The high tax-take country with some civil-war experience is France and the peaceful country with taxes above 40% of GDP and midrange property-rights protection is Botswana.

Figure 1.5 revisits the fiscal-cum-legal capacity plot, once again, when the observations are subdivided by their scores on the 2009 State Fragility Index— i.e., the index underlying Figure 1.2. Here, the correlation is even starker. When we classify countries by having some fragility or not, the observations divide almost perfectly into a nonfragile, high-state-capacity group and a fragile, low-state-capacity group.

Figure 1.4 Legal and fiscal capacity conditional on civil war.

Figure 1.5 Legal and fiscal capacity conditional on fragility.

1.2 The Main Questions

One of the primary purposes of this book is to explain why development clusters, as seen in Figures 1.3 to 1.5. To better understand such patterns in the data, we basically have to pose—and answer—three general questions:

1. What forces shape the building of different s]tate capacities and why do these capacities vary together?

2. What factors drive political violence in its different forms?

3. What explains the clustering of state institutions, violence, and income?

Adam Smith saw things very clearly more than 250 years ago when he wrote the passage quoted at the beginning of this chapter. Smith listed “peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice” as sufficient conditions for prosperity. His three pillars of prosperity are broadly the same as ours, although with a somewhat different emphasis. For us, peace refers to the absence of internal conflict (and political repression) rather than international wars. Indeed, we argue that the latter can even be a force for effective state building. For us, easy taxes means taxes that are easily extracted and broad-based—not a statement about the level. Further, for us, the analysis of justice means finding ways of ensuring that the state supports contracts, enforces property rights, and limits (public or private) predation. Subject to this slight change of focus, our three main questions basically become an inquiry into the circumstances that enable nations to erect Smith's three pillars of prosperity.

In this endeavor, we pool together ideas from four broad research agendas: (1) the study of long-run development and its determinants, (2) the study of civil wars and other forms of internal conflict, (3) the study of the importance of history for today's patterns of development, and (4) the study of how economics and politics interact in shaping societal outcomes. Thus, our work builds on many earlier strands of scholarship, and in what follows we try to give due credit to our predecessors in the large and in the small.

When grappling with the three central questions, we draw extensively on our own research during the last few years on the economics and politics of state building and violence in the process of development [see, e.g., Besley and Persson (2009b, 2010a,b, 2011)]. Even though we rely heavily on this earlier research, the book goes far beyond our articles and papers ...